Le Magnifiche Ribelli (1917-1921)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence in Interwar France

Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence in Interwar France Richard Sonn University of Arkansas On a clear, beautiful day in the center of the city of Paris I performed the first act in front of the entire world. 1 Scholom Schwartzbard, letter from La Santé Prison In this letter to a left-wing Yiddish-language newspaper, Schwartzbard explained why, on 25 May 1926, he killed the former Hetman of the Ukraine, Simon Vasilievich Petliura. From 1919 to 1921, Petliura had led the Ukrainian National Republic, which had briefly been allied with the anti-communist Polish forces until the victorious Red Army pushed both out. Schwartzbard was a Jewish anarchist who blamed Petliura for causing, or at least not hindering, attacks on Ukrainian Jews in 1919 and 1920 that resulted in the deaths of between 50,000 and 150,000 people, including fifteen members of Schwartzbard's own family. He was tried in October 1927, in a highly publicized court case that earned the sobriquet "the trial of the pogroms" (le procès des pogroms). The Petliura assassination and Schwartzbard's trial highlight the massive immigration into France of central and eastern European Jews, the majority of working-class 1 Henry Torrès, Le Procès des pogromes (Paris: Editions de France, 1928), 255-7, trans. and quoted in Felix and Miyoko Imonti, Violent Justice: How Three Assassins Fought to Free Europe's Jews (Amherst, MA: Prometheus, 1994), 87. 392 Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence 393 background, between 1919 and 1939. The "trial of the pogroms" focused attention on violence against Jews and, in Schwartzbard's case, recourse to violence as resistance. -

Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War.Pdf

NESTOR MAKHNO IN THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR Michael Malet THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE TeutonicScan €> Michael Malet \982 AU rights reserved. No parI of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, wilhom permission Fim ed/lIOn 1982 Reprinted /985 To my children Published by lain, Saffron, and Jonquil THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London rind BasingSloke Compafl/u rind reprutntatiW!S throughout the warld ISBN 0-333-2S969-6 Pnnted /II Great Bmain Antony Rowe Ltd, Ch/ppenham 5;landort � Signalur RNB 10043 Akz.·N. \d.·N. I, "'i • '. • I I • Contents ... Acknowledgements VIII Preface ox • Chronology XI .. Introduction XVII Glossary xx' PART 1 MILITARY HISTORY 1917-21 1 Relative Peace, 1917-18 3 2 The Rise of the Balko, July 19I5-February 1919 13 3 The Year 1919 29 4 Stalemate, January-October 1920 54 5 The End, October I92O-August 1921 64 PART 2 MAKHNOVSCHYNA-ORGAN1SATION 6 Makhno's Military Organisation and Capabilities 83 7 Civilian Organisation 107 PART 3 IDEOLOGY 8 Peasants and Workers 117 9 Makhno and the Bolsheviks 126 10 Other Enemies and Rivals 138 11 Anarchism and the Anarchists 157 12 Anti-Semitism 168 13 Some Ideological Questions 175 PART 4 EXILE J 4 The Bitter End 183 References 193 Bibliography 198 Index 213 • • '" Acknowledgements Preface My first thanks are due to three university lecturers who have helped Until the appearance of Michael PaJii's book in 1976, the role of and encouraged me over the years: John Erickson and Z. A. B. Nestor Makhno in the events of the Russian civil war was almost Zeman inspired my initial interest in Russian and Soviet history, unknown. -

Bibliographical Essay

EMMA GOLDMAN: A GUIDE TO HER LIFE AND DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Candace Falk, Editor and Director Stephen Cole, Associate Editor Sally Thomas, Assistant Editor BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY THE WORLD OF EMMA GOLDMAN In 1969, nearly sixty years after it first appeared, Dover Publications published a paperback edition of Emma Goldman's Anarchism and Other Essays. A quarter-century later Dover still sells fifteen hundred copies annually, and its 1970 paperback edition of her autobiography, Living My Life (1931), also remains in print--testimony to the continuing interest in Goldman's life and ideas. With the publication of the microfilm edition of The Emma Goldman Papers, researchers will be able to supplement these volumes and other collections of Goldman's work with facsimiles of her correspondence, government surveillance and legal documents, and other published and unpublished writings on an extraordinary range of issues. The purpose of this essay is to assist users of the microfilm who are unfamiliar with Goldman's historical milieu by alerting them to books--secondary sources identified in the course of the Project's fourteen years of research--that will provide context for the documents in the collection. It is not intended to be a comprehensive bibliography; it is confined for the most part to books, excluding, for example, articles in scholarly journals as well as anarchist newspapers and pamphlets. Included, however, are accounts by Goldman and her associates of the movements and conflicts in which they participated that are essential for an appreciation of the flavor of their culture and of the world they attempted to build. Over the years, many of these sources have been reprinted; others have remained out of print for decades (for example, Alexander Berkman's Bolshevik Myth). -

Osvaldo Bayer Is Dead

Number 97-98 £1 or $2 Feb. 2019 Osvaldo Bayer is Dead One of Argentina’s most highly respected intellectuals, His activism led to his being targeted by the Triple the journalist and historian Osvaldo Bayer has died. A (Argentinean Anti-Communist Alliance) during the His revisionist approach to labour’s struggles and the government of Maria Estela Martínez de Perón and in repression of the organized workers introduced a 1975 he left for exile in Berlin. Some of his books car- watershed into the interpretation of Argentina’s his- ried titles such as The Anarchist Expropriators, tory. The slaughter of the peons, featured in his invest- Severino Di Giovanni: Violent Idealist, Argentinian igation Rebellion in Patagonia, maybe his best-known Football, Rebellion and Hope. He also wrote the book. For that and for other research cataloguing the screenplay for La Patagonia Rebelde, the movie direc- repression enforced by Argentina’s ruling classes and ted by Héctor Olivera exposing the massacre of patrician families, he was censured, harassed and Patagonian peasant labourers. threatened. He was forced into exile and was one of In 2008 he wrote the screenplay and illustrated book the voices outside the country denouncing the state published by Pagina/12. Called Awka Liwen and co- repression of the most recent civilian-military dictator- produced with Mariano Aiello and Kristina Hille, it ship. Upon coming home in the 1980s, he stood by his reported on the confiscation of the lands of native and beliefs. He published his articles in Pagina/12. He peasant communities and on the destruction of the showed up at every protest by workers, peasants and soil. -

Download De Nieuwste Boekberichten

Boekberichten 65, Februari 2020 van de boekhandels Het Fort van Sjakoo & Rosa Inclusief tweedehands boeken catalogus nr. 53 van boekhandel Rosa Thema: Feminisme & Vrouwen Boekhandel Het Fort van Sjakoo Boekhandel Rosa Jodenbreestraat 24 Oliemulderweg 43 1011 NK Amsterdam 9713 VA Groningen ma-vr: 11-18.00 uur Openingstijden: dinsdag 13-17.00 uur zat: 11-17.00 uur en op afspraak [email protected] [email protected] http://www.sjakoo.nl http://www.bookshoprosa.org 1 INTERNATIONAL BOEKHANDEL ROSA, BOOKSHOP HET FORT GRONINGEN VAN SJAKOO Oliemulderweg 43 , 9713 VA, Groningen, Nederland. Tel.: 050-3133247, email: Jodenbreestraat 24, 1011 NK, Amsterdam, [email protected] , internet: Nederland, tel.: 020-6258979, email: http://www.bookshoprosa.org . [email protected] , internet: Openingstijden: elke dinsdag 13-17.00 uur http://www.sjakoo.nl . Openingstijden: maandag-vrijdag: 11.00-18.00 uur, zaterdag: of op afspraak 11.00-17.00 uur. Rosa is een linkse politieke Al sinds november 1977 is het Fort van Sjakoo boekhandel, gevestigd aan de gespecialiseerd in Jodenbreestraat 24. Dit anarchisme, pand werd in 1975 gekraakt feminisme, uit protest tegen de sloop socialisme en voor een kantoorpand. Het verschillende werd door de krakers vormen van bewoonbaar gemaakt en op activisme. Het de benedenverdieping werd assortiment bestaat een boekwinkel ingericht. uit tweedehands, Het verzet van de krakers nieuwe en was succesvol: het pand antiquarische werd niet gesloopt. In de boeken, jaren tachtig kocht de gemeente het pand voor een tijdschriften, t- habbekrats van een speculant en de bewoners en de shirts, speldjes, boekwinkel werden huurders. Het Woningbedrijf buttons, opnaaiers, Amsterdam was toen nog van de gemeente en kreeg zo kaartjes en muziek. -

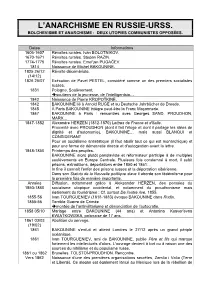

L'anarchisme En Russie-URSS

l’anarchisme en Russie-URSS. Bolchevisme et anarchisme : Deux utopies communistes opposées. Dates Informations 1814 Naissance de Michel BAKOUNINE. 1842 Naissance de KROPOTKINE. 1862-63 TOLSTOÏ édite la revue pédagogique Iasnaïa Poliana. 1864 BAKOUNINE fonde l’Alliance Révolutionnaire Socialiste. 1869 Naissance d’Emma GOLDMAN (1869-1940). 1870 Naissance d’Alexandre BERKMAN (1870-1935). 1873 Michel BAKOUNINE « L’État et l’anarchie ». 1876 1/07 Mort de BAKOUNINE. 1883 TOLSTOÏ publie « Que devons nous faire ? ». 1892 Genève. Fondation Librairie Anarchiste. 1898 MAKHAÏSKI (VOLSKI) « Le travailleur intellectuel ». 1901 Londres : TOLSTOÏ publie « Svobodnoe Slovo » (Libre Parole). 1901 TOLSTOÏ est excommunié. 1902 En Russie : groupe anarcho-syndicaliste de SANDOMIRSKI. 1903 Russie : début des groupes de Chernoe Znamia. Genève. groupe kropotkinien Khleb i volia, avec notamment GROSSMAN 1903-1905 (ROCHTCHINE). 1903 fin scission de Khleb i volia : groupe terroriste de GOGUELIA. London : Réunion d’anarchistes russes appelant à la Révolution Sociale et 1904 s’opposant aux marxistes. 1905 Essor du mouvement anarchiste en Russie. 1905 01/01 « Premier » soviet avec VOLINE à Petrograd, qui en refuse la présidence. 1905 09/01 « Dimanche de sang ». 1905 printemps Paris. BIDBEI fonde le Listok Gruppy Beznachalie. 1905 13/10 Soviet de Petrograd avec présence anarchiste. Attentats anarchistes : 1905 nov.-déc. - Hôtel Bristol de Varsovie - Café Liberman d’Odessa. 1905 Moscou : insurrection ouvrière. 1905 Groupe anarcho-communiste de combat de ROMANOV : les beznatchaltsi. Nouvelles scissions des tchernoznamientsi : 1905-1906 - les communari-obschtchiniki pour l’occupation des unités de production – les bezmotivniki plutôt terroristes. 1906 janvier Kishinev. Conférence de Chernoe Znamia. 1906 juillet Paris. Fondation de « Burevestnik » important journal avec N.ROGDAEV. -

Emma Goldman

12 Memoria storica Storia per immagini Album di famiglia Da Mary a Emma Storie di donne davanti la Biografie (al femminile) cinepresa di ordinaria militanza Informazioni editoriali Storia per immagini Testimonianze orali Amsterdam: Storie di donne dietro la Anna e Aldo l’archivio degli archivi cinepresa 4 Cose nostre • Ecoutez May Picqueray • Quota associativa • Ecoutez Jeanne Humbert • Convegno di studi su anarchismo • De toda la vida ed ebraismo • Voces de Libertad • Donazioni Raccontare la storia armate • Errata Corrige di cinepresa • Fondo Turroni • Nestor Makhno, paysan d’Ukraine • Ricordo di Pier Carlo Masini • Los llamaban los presos de a cura di Lorenzo Pezzica Bragado • Ricordo di Mirella Larizza a cura di Pietro Adamo 42 Album di famiglia Biografie (al femminile) di ordinaria militanza 12 Memoria storica Documenti inediti • Italia: le donne di casa Berneri • Mary Wollstonecraft di Fiamma Chessa • Louise Michel • Francia: Madeleine Vernet • Emma Goldman di Francesco Codello Testimonianze orali • Germania: Etta Federn • Via Vettor Fausto 3 di Hans Müller-Sewing di Fabio Iacopucci • Spagna: Amelia Jover Velasco • Aldo Rossi e Anna Pietroni di Paco Madrid Santos di L.V. • Argentina: Juana Rouco Buela • Sulle fonti storiche di Eduardo Colombo di Amedeo Bertolo • Inghilterra/USA: Nellie Dick Anarchivi di Nicolas Walter Biblioteca Tullio Francescato • Italia: Emma Neri Garavini di Gianpiero Landi 27 Informazioni editoriali 61 Varie ed eventuali Amsterdam: l’archivio degli archivi Curiosità di Dino Taddei • Letti e approvati • Confessioni d’autore 29 Storia per immagini • Anedoctica Mostre • E vai col liscio Cinquanta donne per l’anarchia • Politicamente scorretto Film Ritratti militanti Hanno collaborato a questo numero, oltre agli autori delle varie schede informative, Ornella Buti, Rossella Di Leo, Lorenzo Pezzica, Dino Taddei per la redazione testi e Fabrizio Villa per la redazione grafica. -

The Assassination of Symon Petliura and the Trial of Scholem Schwarzbard 1926–1927 a Selection of Documents

THE ASSASSINATION OF SYMON PETLIURA AND THE TRIAL OF SHOLEM SCHWARZBARD 1926–1927 A Selection of Documents Edited by David Engel The Assassination of Symon Petliura and the Trial of Sholem Schwarzbard 1926–1927 Schwarzbard of Sholem the Trial and Petliura of Symon Assassination The archiv jüdischer geschichte und kultur Band 2 David Engel 978-3-525-30195-1_Eber.indd 1 19.09.2018 14:52:56 Archiv jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur Archive of Jewish History and Culture Band/Volume 2 Im Auftrag der Sächsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig On behalf of the Saxonian Academy of Sciences and Humanities at Leipzig herausgegeben/edited von/by Dan Diner Redaktion/editorial staff Frauke von Rohden Stefan Hofmann Markus Kirchhoff Ulrike Kramme Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht The Assassination of Symon Petliura and the Trial of Scholem Schwarzbard 1926–1927 A Selection of Documents Selected, translated, annotated, and introduced by David Engel The “Archive of Jewish History and Culture” is part of the research project “European Traditions – Encyclopedia of Jewish Cultures” at the Saxonian Academy of Sciences and Humanities at Leipzig. It is sponsored by the Academy program of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Free State of Saxony. The Academy program is coordinated by the Union of the German Academies of Sciences and Humanities. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data available online: https://dnb.de © 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D37073 Göttingen Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz, Lemförde Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2566-6673 ISBN (Print) 978-3-525-31027-4 ISBN (PDF) 978-3-666-31027-0 https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666310270 This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International license, at DOI 10.13109/9783666310270. -

L'anarchisme En Russie-Urss

L’ANARCHISME EN RUSSIE-URSS. BOLCHEVISME ET ANARCHISME : DEUX UTOPIES COMMUNISTES OPPOSÉES. Dates Informations 1606-1607 Révoltes rurales. Ivan BOLOTNIKOV. 1670-1671 Révoltes rurales. Stepan RAZIN. 1774-1775 Révoltes rurales. Emel'jan PUGAČEV. 1814 Naissance de Michel BAKOUNINE. 1825 26/12 Révolte décembriste. (14/12) 1826 25/07 Exécution de Pavel PESTEL, considéré comme un des premiers socialistes russes. 1831 Pologne. Soulèvement. ➔soutiens de la jeunesse, de l'intelligentsia… 1842 Naissance de Pierre KROPOTKINE. 1842 BAKOUNINE lié à Arnold RUGE et au Deutsche Jahrbücher de Dresde. 1845 À Paris BAKOUNINE intègre peut-être la Franc Maçonnerie. 1847 BAKOUNINE à Paris : rencontres avec Georges SAND, PROUDHON, MARX… 1847-1852 Alexandre HERZEN (1812-1870) Lettres de France et d'Italie. Proximité avec PROUDHON (dont il fait l'éloge et dont il partage les idées de dignité et d'autonomie), BAKOUNINE… mais aussi BLANQUI et CONSIDERANT Pour un socialisme antiétatique (il faut abolir tout ce qui est monarchique) et pour une forme de démocratie directe et d'autogestion avant la lettre. 1848-1850 Printemps des peuples. BAKOUNINE alors plutôt panslaviste et réformateur participe à de multiples soulèvements en Europe Centrale. Plusieurs fois condamné à mort, il subit prisons, extraditions, déportations entre 1850 et 1861… In fine il connaît l'enfer des prisons russes et la déportation sibérienne. Dans son Statuts de la Nouvelle politique slave il aborde son fédéralisme pour la première fois de manière importante. Années Diffusion, notamment grâce à Aleksander HERZEN, des pensées du 1850-1860 socialisme utopique occidental, et notamment du proudhonisme mais également du fouriérisme ; Cf. surtout De l'autre rive, 1855. -

Looking Back at the Back Issues

Number 100-101 £1 or $2 Jan. 2020 Looking back at the back issues It seemed a simple idea: look through back issues of going on to not just ‘celebrate’ anarchism and the Kate Sharpley Library’s bulletin to find some anarchists but to worry at the ‘rough edges’ of what interesting articles, and then encourage people to read we know (or think we know). Here’s Barry Pateman them and think about anarchist history. The stuff is talking about the dangers historians (‘however there, it’s just it got me thinking about history too. anarchist they are’) face: ‘The rough edges of I already knew I should mention tributes we printed anarchism, as well as the apparently smooth and to historians who influenced us like Antonio Téllez straightforward areas, should be their territory; the and Paul Avrich. [1] Then there’s the profile of Andre contradictions that initially puzzle and the anomalies Prudhommeaux, back when we thought we could that are too worrying to ignore. Historians should be number the unknown anarchists we were commemor- the irritatingly sober person at the party warning you ating (and is this the first piece Paul Sharkey not to get too pissed on the historical correctness of translated?) [2] your ideas. The awkward truth is that mining seams of What really struck me, though, were the patterns. anarchist history purely in the light of our own present There are lots of loose threads: ‘This pamphlet is pre-occupations is at best ahistorical and at worst coming soon,’ and it never does, or ten years later.