Notes on the Transformation of 'Dravidian Ideology'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Un/Selfish Leader Changing Notions in a Tamil Nadu Village

The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Björn Alm The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Doctoral dissertation Department of Social Anthropology Stockholm University S 106 91 Stockholm Sweden © Björn Alm, 2006 Department for Religion and Culture Linköping University S 581 83 Linköping Sweden This book, or parts thereof, may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. ISBN 91-7155-239-1 Printed by Edita Sverige AB, Stockholm, 2006 Contents Preface iv Note on transliteration and names v Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Structure of the study 4 Not a village study 9 South Indian studies 9 Strength and weakness 11 Doing fieldwork in Tamil Nadu 13 Chapter 2 The village of Ekkaraiyur 19 The Dindigul valley 19 Ekkaraiyur and its neighbours 21 A multi-linguistic scene 25 A religious landscape 28 Aspects of caste 33 Caste territories and panchayats 35 A village caste system? 36 To be a villager 43 Chapter 3 Remodelled local relationships 48 Tanisamy’s model of local change 49 Mirasdars and the great houses 50 The tenants’ revolt 54 Why Brahmans and Kallars? 60 New forms of tenancy 67 New forms of agricultural labour 72 Land and leadership 84 Chapter 4 New modes of leadership 91 The parliamentary system 93 The panchayat system 94 Party affiliation of local leaders 95 i CONTENTS Party politics in Ekkaraiyur 96 The paradox of party politics 101 Conceptualising the state 105 The development state 108 The development block 110 Panchayats and the development block 111 Janus-faced leaders? 119 -

Socio-Religious Desegregation in an Immediate Postwar Town Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Carnets de géographes 2 | 2011 Espaces virtuels Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon Madavan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 DOI: 10.4000/cdg.2711 ISSN: 2107-7266 Publisher UMR 245 - CESSMA Electronic reference Delon Madavan, « Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town », Carnets de géographes [Online], 2 | 2011, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 07 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 ; DOI : 10.4000/cdg.2711 La revue Carnets de géographes est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon MADAVAN PhD candidate and Junior Lecturer in Geography Université Paris-IV Sorbonne Laboratoire Espaces, Nature et Culture (UMR 8185) [email protected] Abstract The cease-fire agreement of 2002 between the Sri Lankan state and the separatist movement of Liberalisation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was an opportunity to analyze the role of war and then of the cessation of fighting as a potential process of transformation of the segregation at Jaffna in the context of immediate post-war period. Indeed, the armed conflict (1987-2001), with the abolition of the caste system by the LTTE and repeated displacements of people, has been a breakdown for Jaffnese society. The weight of the hierarchical castes system and the one of religious communities, which partially determine the town's prewar population distribution, the choice of spouse, social networks of individuals, values and taboos of society, have been questioned as a result of the conflict. -

Page BRAHMANISM, BRAHMINS and BRAHMIN TAMIL in the CONTEXT of SPEECH to TEXT TECHNOLOGY Corresponding Email:[email protected]

BRAHMANISM, BRAHMINS AND BRAHMIN TAMIL IN THE CONTEXT OF SPEECH TO TEXT TECHNOLOGY R S Vignesh Raja, Ashik Alib Dr. BabakKhazaeic aResearch degree student, cSenior Lecturer Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom bSoftware Developer Fireflyapps Limited, Sheffield, United Kingdom Corresponding email:[email protected] Abstract Brahmanism in today's world is largely viewed as a 'caste' within Hinduism than its predecessor religion. This research paper explores the impact and influence religious affiliation could have on using certain advanced technologies such as the voice-to-text. This research paper attempts to reintroduce Brahmanism as a distinct religion and justifies through an empirical study and other literature as to why it is important, more specifically in language-related technology. Keywords: Tamil; speech to text; technology; Brahmanism; Brahmins 1. Introduction Speech-to-text is a fascinating area of research. The speech-to-text system exists for popular languages such as English. Whilst dealing with the user acceptance of technology, previous experiments suggest that it is vital to consider the religious affiliation as it could influence 'pronunciation' which is perceived to be very important for the users to be able to use voice-to- text technology in syllabic languages such as Tamil (Rama et al., 2002). Some of the previous experiments have identified the effect of code mixing, mispronunciation or in some cases the inability to correctly pronounce a syllable by the native Tamil speakers (Raj, Ali&Khazaei, 2015). This research paper aims to look into the code mixing and pronunciation aspects of 'Brahmin Tamil'- a dialect of Tamil spoken by the Brahmins who speak Tamil as their mother tongue. -

The Fault Lines in Tamil Nadu That the DMK Now Has to Confront

TIF - The Fault Lines in Tamil Nadu that the DMK Now Has to Confront KALAIYARASAN A June 4, 2021 M. VIJAYABASKAR Is modernisation of occupations in Tamil Nadu possible? A young worker at a brick factory near Chennai | brianindia/Alamy The DMK faces new challenges in expanding social justice alongside economic modernisation: internal fault lines have emerged in the form of cracks in the Dravidian coalition of lower castes and there are external ones such as reduced autonomy for states. As anticipated, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)-led alliance has come to power in Tamil Nadu after winning 159 out of the 234 seats in the state assembly. Many within the party had expected it to repeat its 2019 sweep in the Lok Sabha elections. The All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), despite having been in power for a decade and losing its long-time leader J. Jayalalithaa, managed to retain a good share of its vote base. The AIADMK government was often seen to compromise the interests of the state because of pressure from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), with which it had allied. The DMK’s election campaign had, therefore, emphasised the loss of the state’s dignity and autonomy because of the AIADMK-BJP alliance and promised a return to the Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in June 4, 2021 Dravidian ethos that had earlier informed the state’s development. Apart from welfare, the DMK’s election manifesto emphasised reforms in governance of service delivery, and growth across sectors, agriculture in particular. The DMK’s victory has come at a time when Tamil Nadu is faced with a series of challenges. -

'Personality Politics Died with Amma'

'Personality politics died with Amma' 'I don't think after Amma, the cult of personality will endure.' 'I think there will be a shift back to the politics of ideology and principles rather than a cult of personality.' P T R Palanivel Thiagarajan is the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam MLA from the Madurai Central constituency. A former America-based merchant banker, he returned to Tamil Nadu to contest a seat his father P T R Palanivel Rajan had represented in the state assembly. His observations during the discussions on the budget in the assembly were acknowledged by then chief minister J Jayalalithaa. P T R Palanivel Thiagarajan draws the trajectory of Tamil Nadu politics after Jayalalithaa's death. It will be difficult for All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam members to find a common cause. They had a towering personality for a leader and filling that vacuum will not be possible. I don't see another leader taking her place in the near future. There is nobody of her stature. It is a generational shift and in her case the successor is not obvious. It is a inter generational transfer. It started with Perarignar Anna (the late Tamil Nadu CM C N Annadurai, founder of the DMK and the inspiration for the AIADMK) and then MGR (the late Tamil Nadu CM M G Ramachandran). With Anna, the politics was based on ideology which was different from the earlier Congress government in Tamil Nadu. During MGR's time, it was a big shift from ideology governance to a personality cult. With the DMK and the Congress, there was a marked difference in ideology. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

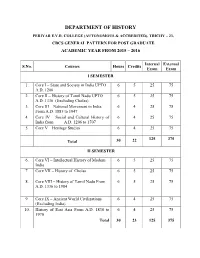

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

The Political Aco3mxddati0n of Primqpjdial Parties

THE POLITICAL ACO3MXDDATI0N OF PRIMQPJDIAL PARTIES DMK (India) and PAS (Malaysia) , by Y. Mansoor Marican M.Soc.Sci. (S'pore), 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FL^iDlMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of. Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforniing to the required standard THE IJNT^RSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November. 1976 ® Y. Mansoor Marican, 1976. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of POLITICAL SCIENCE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This study is rooted in a theoretical interest in the development of parties that appeal mainly to primordial ties. The claims of social relationships based on tribe, race, language or religion have the capacity to rival the civil order of the state for the loyalty of its citizens, thus threatening to undermine its political authority. This phenomenon is endemic to most Asian and African states. Most previous research has argued that political competition in such contexts encourages the formation of primordially based parties whose activities threaten the integrity of these states. -

The 2001 Assembly Elections in Tamil Nadu

NEW ALIGNMENTS IN SOUTH INDIAN POLITICS The 2001 Assembly Elections in Tamil Nadu A. K. J. Wyatt There has been a strong regional pattern to the politics of modern Tamil Nadu, intimately related to the caste stratification of Tamil society. In contrast to other parts of India, upper-caste brahmins constitute a very small proportion (approximately 3%) of the population of Tamil Nadu. Roughly two-thirds of the 62 million population belong to the middle group of “backward” castes. Though this umbrella term is widely used, it is some- what misleading. Members of these castes do not enjoy high ritual status in the caste system, hence the term “backward,” but they occupy a wide variety of socioeconomic positions in Tamil society. For example, during the colo- nial period, some members of the backward castes were wealthy owners of land and businesses. These leading members of the backward castes resented brahmin dominance of politics and the professions under British colonial rule.1 In particular, in the early 20th century, many considered the Indian National Congress to be an elitist and socially exclusive organization. E. V. Ramaswami Naicker asserted himself as a spokesman against brahmin he- A. K. J. Wyatt is Lecturer in the Department of Politics at the Univer- sity of Bristol, Bristol, U.K. The author is very grateful to the Society for South Asian Studies and the University of Bristol Staff Travel Fund for contributing to the cost of two visits to Tamil Nadu in 2000 and 2001. During these visits, he was able to interview a selection of senior politicians from across the range of parties. -

Ma Regular.Pdf

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY- TIRUCHIRAPPALLI MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM for Candidates 2018-2019 onwards Semester - Course Instruct Credit Marks Total I ion Internal External Credits-25 Hours 1. Evolution of Ideas and 6 5 25 75 100 Institutions in Ancient India [HIS1CC1] (including Map study) 2. Evolution of Ideas and 6 5 25 75 100 Institutions in Medieval India [HIS1CC2] (including Map study) 3. Colonialism and 6 5 25 75 100 Nationalism in Modern India [ HIS1CC3 ] 4. Political History of Tamil 6 5 25 75 100 Nadu from Early times to 1565 [HIS1CC4] 5. History of Contemporary 6 6 25 75 100 India: Challenges and Perspectives [ HIS1CC5] Semester - 6. Research Methods in 6 5 25 75 100 II History [HIS2CC6] Credits-22 7. Revolutions in Europe 6 5 25 75 100 1914-1991 [HIS2CC7] 8. Colonialism and 6 5 25 75 100 Nationalism in Tamil Nadu [HIS2CC8] 9. Elective (Major Based) 6 5 25 75 100 Elective Paper [ HIS2EC1] 10. Elective (Non-Major Based) 3 2 25 75 100 Constitution for Competitive Examination [HIS2EDC1] Semester - 11. History of Science 6 5 25 75 100 III and Technology Credits-22 [HIS3CC9] 12. Elective (Major 6 5 25 75 100 Based) Elective Paper [HIS3EC2] 13.Elective (Non-Major Based) 3 2 25 75 100 Science, Technology and Society [HIS3EDC2] 14. Project Work 10 25 75 100 Semester 15. Human Rights 6 5 25 75 100 – IV [HIS4CC10] Credits-21 16. International 6 5 25 75 100 Relations [HIS4CC11] 17. Environmental 6 5 25 75 100 History [HIS4CC12 ] 18. -

Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu

Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu John Harriss with Andrew Wyatt Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 50/2016 | March 2016 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 50/2016 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Harriss, John and Wyatt, Andrew, Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 50/2016, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, March 2016. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright remains with the author. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Copyright for this issue: John Harriss, jharriss (at) sfu.ca. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu 3 Business and Politics in Tamil Nadu Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

The Story of Patronage and Populism in the State of Tamil Nadu India

ERPI 2018 International Conference Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World Conference Paper No.24 Title-Bovine Nationalism: The Story of Patronage and Populism in the State of Tamil Nadu, India Dr. Lavanya Suresh 17-18 March 2018 International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Netherlands Organized jointly by: In collaboration with: Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the authors in their private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of organizers and funders of the conference. March, 2018 Check regular updates via ERPI website: www.iss.nl/erpi ERPI 2018 International Conference - Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World Title-Bovine Nationalism: The Story of Patronage and Populism in the State of Tamil Nadu, India Dr. Lavanya Suresh Introduction The death of the sitting Chief Minister of the State of Tamil Nadu and the head of the ruling party All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), J. Jayalalithaa, on 6th December, 2016 destabilised a two-party dominated system of elections. From the 1970’s onward Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and its political rival All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) have been the major parties in the State and represented the Dravidian politics in the region. After the death of the head of the AIADMK, Jayalalithaa, a close aid of hers V.K. Sasikala, tried to take over, but on 14 February 2017, a two-bench Supreme Court jury pronounced her guilty and ordered her immediate arrest in a disproportionate-assets case, effectively ending her Chief Ministerial ambitions. This has led to political turmoil in the state, which has been capitalised on by the right-wing party that controls the central government, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).