Dmk from 1949 – 1956

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTEMPORARY INDIA and EDUCATION.Pdf

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY TIRUCHIRAPPALLI – 620 024 CENTRE FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION CONTEMPORARY INDIA AND EDUCATION B.Ed. I YEAR (Copyright reserved) For Private Circulation only Chairman Dr.V.M.Muthukumar Vice-Chancellor Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Vice-Chairman Dr.C.Thiruchelvam Registrar Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Course Director Dr. R. Babu Rajendran Director i/c Centre for Distance Education Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Course Material Co-ordinator Dr.K.Anandan Professor & Head, Dept .of Education Centre for Distance Education Bharathidasan University Tiruchirapplli-620 024 Author Dr.R.Portia Asst.Professor Alagappa University College of Education Karaikudi,Sivaganga(Dt.) The Syllabus adopted from 2015-16 onwards Core - II: CONTEMPORARY INDIA AND EDUCATION Internal Assessment: 25 Total Marks: 100 External Assessment: 75 Examination Duration: 3 hrs. Objectives: After the completion of this course the student teacher will be able 1. To understand the concept and aims of Education. 2. To develop understanding about the social realities of Indian society and its impact on education 3. To learn the concepts of social Change and social transformation in relation to education 4. To understand the educational contributions of the Indian cum western thinkers 5. To know the different values enshrined in the constitution of India and its impact on education 6. To identify the contemporary issues in education and its educational implications 7. To understand the historical developments in policy framework related to education Course Content: UNIT-I Concept and Aims Education Meaning and definitions of Education-Formal, non-formal and informal education Various levels of Education-Objectives-pre-primary, primary, secondary and higher secondary education and various statuary boards of education -Aims of Education in Contemporary Indian society Determinants of Aims of Education. -

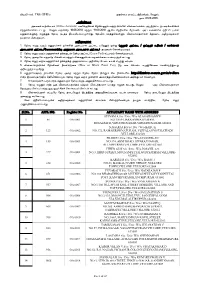

Sl.No. APPL NO. Register No. APPLICANT NAME WITH

tpLtp vz;/ 7166 -2018-v Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;wk;. ntYhh;. ehs; 01/08/2018 mwptpf;if mytyf cjtpahsh; (Office Assistant) gzpfSf;fhd fPH;f;fhqk; kDjhuh;fspd; tpz;zg;g';fs; mLj;jfl;l eltof;iff;fhf Vw;Wf;bfhs;sg;gl;lJ/ nkYk; tUfpd;w 18/08/2018 kw;Wk; 19/08/2018 Mfpa njjpfspy; fPH;f;fz;l ml;ltizapy; Fwpg;gpl;Ls;s kDjhuh;fSf;F vGj;Jj; njh;t[ elj;j jpl;lkplg;gl;Ls;sJ/ njh;tpy; fye;Jbfhs;Sk; tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs; fPH;fz;l tHpKiwfis jtwhky; gpd;gw;wt[k;/ tHpKiwfs; 1/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fspd; milahs ml;il VnjDk; xd;W (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il-ntiytha;g;g[ mYtyf milahs ml;il) jtwhky; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 2/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSld; njh;t[ ml;il(Exam Pad) fl;lhak; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 3/ njh;t[ miwapy; ve;jtpj kpd;dpay; kw;Wk; kpd;dDtpay; rhjd’;fis gad;gLj;jf; TlhJ/ 4/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSf;F mDg;gg;gl;l mwptpg;g[ rPl;il cld; vLj;J tut[k;/ 5/ tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs;; njh;tpid ePyk;-fUik (Blue or Black Point Pen) epw ik bfhz;l vGJnfhiy gad;gLj;JkhW mwpt[Wj;jg;gLfpwJ/ 6/ kDjhuh;fSf;F j’;fspd; njh;t[ miw kw;Wk; njh;t[ neuk; ,d;Dk; rpy jpd’;fspy; http://districts.ecourts.gov.in/vellore vd;w ,izajsj;jpy; bjhptpf;fg;gLk;/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; Kd;dnu midj;J tptu’;fisa[k; mwpe;J tu ntz;Lk;/ 7/ fhyjhkjkhf tUk; ve;j kDjhuUk; njh;t[ vGj mDkjpf;fg;glkhl;lhJ/ 8/ njh;t[ vGJk; ve;j xU tpz;zg;gjhuUk; kw;wth; tpilj;jhis ghh;j;J vGjf; TlhJ. -

Self Respect Movement Under Periyar

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 SELF RESPECT MOVEMENT UNDER PERIYAR M. Nala Assistant Professor of History Sri Sarada College for Women (Autonomous), Salem- 16 Self Respect Movement represented the Dravidian reaction against the Aryan domination in the Southern Society. It also armed at liberating the society from the evils of religious, customs and caste system. They tried to give equal status to the downtrodden and give the social dignity, Self Respect Movement was directed by the Dravidian communities against the Brahmanas. The movement wanted a new cultural society more based on reason rather than tradition. It aimed at giving respect to the instead of to a Brahmin. By the 19th Century Tamil renaissance gained strength because of the new interest in the study of the classical culture. The European scholars like Caldwell Beschi and Pope took a leading part in promoting this trend. C.V. Meenakshi Sundaram and Swaminatha Iyer through their wirtings and discourse contributed to the ancient glory of the Tamil. The resourceful poem of Bharathidasan, a disciple of Subramania Bharati noted for their style, beauty and force. C.N. Annadurai popularized a prose style noted for its symphony. These scholars did much revolutionise the thinking of the people and liberate Tamil language from brahminical influence. Thus they tried resist alien influence especially Aryan Sanskrit and to create a new order. The chief grievance of the Dravidian communities was their failure to obtain a fair share in the administration. Among then only the caste Hindus received education in the schools and colleges, founded by the British and the Christian missionaries many became servants of the Government, of these many were Brahmins. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY, TIRUCHIRAPPALLI 620 024 B.A. HISTORY Programme – Course Structure Under CBCS (Applicable to the Ca

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY, TIRUCHIRAPPALLI 620 024 B.A. HISTORY Programme – Course Structure under CBCS (applicable to the candidates admitted from the academic year 2010 -2011 onwards) Sem. Part Course Ins. Credit Exam Marks Total Hrs Hours Int. Extn. I Language Course – I (LC) – 6 3 3 25 75 100 Tamil*/Other Languages +# II English Language Course - I (ELC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 I III Core Course – I (CC) History of India 5 4 3 25 75 100 from Pre history to 1206 AD Core Course – II (CC) History of India 5 4 3 25 75 100 from 1206 -1707 AD First Allied Course –I (AC) – Modern 5 3 3 25 75 100 Governments I First Allied Course –II (AC) – Modern 3 - @ - - - Governments – II Total 30 17 500 I Language Course – II (LC) - 6 3 3 25 75 100 Tamil*/Other Languages +# II English Language Course – II (ELC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 II III Core Course – III(CC) History of Tamil 6 4 3 25 75 100 nadu upto 1801 AD First Allied Course – II (CC) - Modern 2 3 3 25 75 100 Governments – II First Allied Course – III (AC) – 5 4 3 25 75 100 Introduction to Tourism Environmental Studies 3 2 3 25 75 100 IV Value Education 2 2 3 25 75 100 Total 30 21 700 I Language Course – III (LC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 Tamil*/Other Languages +# II English Language Course - III (ELC) 6 3 3 25 75 100 III III Core Course – IV (CC) – History of 6 5 3 25 75 100 Modern India from 1707 - 1857AD Second Allied Course – I (AC) – Public 6 3 3 25 75 100 Administration I Second Allied Course – II (AC) - Public 4 - @ - -- -- Administration II IV Non Major Elective I – for those who 2 2 3 25 75 100 studied Tamil under -

The Fault Lines in Tamil Nadu That the DMK Now Has to Confront

TIF - The Fault Lines in Tamil Nadu that the DMK Now Has to Confront KALAIYARASAN A June 4, 2021 M. VIJAYABASKAR Is modernisation of occupations in Tamil Nadu possible? A young worker at a brick factory near Chennai | brianindia/Alamy The DMK faces new challenges in expanding social justice alongside economic modernisation: internal fault lines have emerged in the form of cracks in the Dravidian coalition of lower castes and there are external ones such as reduced autonomy for states. As anticipated, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)-led alliance has come to power in Tamil Nadu after winning 159 out of the 234 seats in the state assembly. Many within the party had expected it to repeat its 2019 sweep in the Lok Sabha elections. The All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), despite having been in power for a decade and losing its long-time leader J. Jayalalithaa, managed to retain a good share of its vote base. The AIADMK government was often seen to compromise the interests of the state because of pressure from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), with which it had allied. The DMK’s election campaign had, therefore, emphasised the loss of the state’s dignity and autonomy because of the AIADMK-BJP alliance and promised a return to the Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in June 4, 2021 Dravidian ethos that had earlier informed the state’s development. Apart from welfare, the DMK’s election manifesto emphasised reforms in governance of service delivery, and growth across sectors, agriculture in particular. The DMK’s victory has come at a time when Tamil Nadu is faced with a series of challenges. -

'Personality Politics Died with Amma'

'Personality politics died with Amma' 'I don't think after Amma, the cult of personality will endure.' 'I think there will be a shift back to the politics of ideology and principles rather than a cult of personality.' P T R Palanivel Thiagarajan is the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam MLA from the Madurai Central constituency. A former America-based merchant banker, he returned to Tamil Nadu to contest a seat his father P T R Palanivel Rajan had represented in the state assembly. His observations during the discussions on the budget in the assembly were acknowledged by then chief minister J Jayalalithaa. P T R Palanivel Thiagarajan draws the trajectory of Tamil Nadu politics after Jayalalithaa's death. It will be difficult for All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam members to find a common cause. They had a towering personality for a leader and filling that vacuum will not be possible. I don't see another leader taking her place in the near future. There is nobody of her stature. It is a generational shift and in her case the successor is not obvious. It is a inter generational transfer. It started with Perarignar Anna (the late Tamil Nadu CM C N Annadurai, founder of the DMK and the inspiration for the AIADMK) and then MGR (the late Tamil Nadu CM M G Ramachandran). With Anna, the politics was based on ideology which was different from the earlier Congress government in Tamil Nadu. During MGR's time, it was a big shift from ideology governance to a personality cult. With the DMK and the Congress, there was a marked difference in ideology. -

The Political Aco3mxddati0n of Primqpjdial Parties

THE POLITICAL ACO3MXDDATI0N OF PRIMQPJDIAL PARTIES DMK (India) and PAS (Malaysia) , by Y. Mansoor Marican M.Soc.Sci. (S'pore), 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FL^iDlMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of. Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforniing to the required standard THE IJNT^RSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November. 1976 ® Y. Mansoor Marican, 1976. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of POLITICAL SCIENCE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This study is rooted in a theoretical interest in the development of parties that appeal mainly to primordial ties. The claims of social relationships based on tribe, race, language or religion have the capacity to rival the civil order of the state for the loyalty of its citizens, thus threatening to undermine its political authority. This phenomenon is endemic to most Asian and African states. Most previous research has argued that political competition in such contexts encourages the formation of primordially based parties whose activities threaten the integrity of these states. -

Chevalior Sivaji Ganesan‟S Tamil Film Songs Not Only Emulated the Quality of the Movie but Also Contains Ethical Imports That

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: A Arts & Humanities - Psychology Volume 20 Issue 10 Version 1.0 Year 2020 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Chevalior Sivaji Ganesan‟S Tamil Film Songs Not Only Emulated the Quality of the Movie but also Contains Ethical Imports that can be Compared with the Ethical Theories – A Retrospective Reflection By P.Sarvaharana, Dr. S.Manikandan & Dr. P.Thiyagarajan Tamil Nadu Open University Abstract- This is a research work that discusses the great contributions made by Chevalior Shivaji Ganesan to the Tamil Cinema. It was observed that Chevalior Sivaji film songs reflect the theoretical domain such as (i) equity and social justice and (ii) the practice of virtue in the society. In this research work attention has been made to conceptualize the ethical ideas and compare it with the ethical theories using a novel methodology wherein the ideas contained in the film song are compared with the ethical theory. Few songs with the uncompromising premise of patni (chastity of women) with the four important charateristics of women of Tamil culture i.e. acham, madam, nanam and payirpu that leads to the great concept of chastity practiced by exalting woman like Kannagi has also been dealt with. The ethical ideas that contain in the selection of songs were made out from the selected movies acted by Chevalier Shivaji giving preference to the songs that contain the above unique concept of ethics. GJHSS-A Classification: FOR Code: 190399 ChevaliorSivajiGanesanSTamilFilmSongsNotOnlyEmulatedtheQualityoftheMoviebutalsoContainsEthicalImportsthatcanbeComparedwiththeEthicalTheo riesARetrospectiveReflection Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2020. -

IEPF-2 Disclosures FY-17-18

TCP Ltd Details of Unclaimed deposits as at the 46th AGM date 26-10-18 For the Financial year ended 31-3-18 (1st Year for IEPF Rule 5 (8) compliance) Unclaimed position as at the 46th AGM held on 26-10-18 - 1st year intimation (the unclaimed status details of the following depositors shall be furnished as at the closure of each of the succeeding 7 AGM's up to the AGM held for the Financial year ended 31-3-25) For the purpose of filing Form IEPF-2 And thereafter it should be remitted to the IEPF within 30 days from the due date Fixed Deposit Serial No. Name Address Nature of Amount Amount Rs. Due date for transfer FDR No. to the IEPF 1 Rajalakshmi Natarajan 28/2, Lakshmi Colony, T. Nagar, Matured deposit 10,000 12/6/2017 16376 Chennai 600017 2 P. Eswaramurthy Old No.36, New No.54, Krishnappa Matured deposit 10,000 5/1/2018 16517 Agraharam Street, Chennai 600079 3 N. Krishna Kumar New No.10, Old No.41, IInd Street, Matured deposit 20,000 8/17/2018 16908 Parthasarathy Nagar, Adambakkam, Chennai 600088 4 L. Janaki 23/48, Rani Anna Nagar, Matured deposit 20,000 9/3/2018 16989 K K Nagar, Chennai 600078 5 Nalini R Pai No.13, A G Colony, Matured deposit 16,000 3/14/2019 17428 Alwar Thirunagar, Chennai 600087 6 P. Ravisekar 24/19, Second Main Road, J B Estate Matured deposit 10,000 11/23/2019 18311 Avadi, Chennai 600054 7 Vasantha Ravindran 1 Sri Devi Apartments, Matured deposit 25,000 5/23/2020 18638 5/2, 4th Trust Cross Street, Mandaveli, Chennai 600028 8 Hemlatha D Tarvady Shri Shraddha', 5/2A, Dr. -

Ma Regular.Pdf

BHARATHIDASAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY- TIRUCHIRAPPALLI MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM for Candidates 2018-2019 onwards Semester - Course Instruct Credit Marks Total I ion Internal External Credits-25 Hours 1. Evolution of Ideas and 6 5 25 75 100 Institutions in Ancient India [HIS1CC1] (including Map study) 2. Evolution of Ideas and 6 5 25 75 100 Institutions in Medieval India [HIS1CC2] (including Map study) 3. Colonialism and 6 5 25 75 100 Nationalism in Modern India [ HIS1CC3 ] 4. Political History of Tamil 6 5 25 75 100 Nadu from Early times to 1565 [HIS1CC4] 5. History of Contemporary 6 6 25 75 100 India: Challenges and Perspectives [ HIS1CC5] Semester - 6. Research Methods in 6 5 25 75 100 II History [HIS2CC6] Credits-22 7. Revolutions in Europe 6 5 25 75 100 1914-1991 [HIS2CC7] 8. Colonialism and 6 5 25 75 100 Nationalism in Tamil Nadu [HIS2CC8] 9. Elective (Major Based) 6 5 25 75 100 Elective Paper [ HIS2EC1] 10. Elective (Non-Major Based) 3 2 25 75 100 Constitution for Competitive Examination [HIS2EDC1] Semester - 11. History of Science 6 5 25 75 100 III and Technology Credits-22 [HIS3CC9] 12. Elective (Major 6 5 25 75 100 Based) Elective Paper [HIS3EC2] 13.Elective (Non-Major Based) 3 2 25 75 100 Science, Technology and Society [HIS3EDC2] 14. Project Work 10 25 75 100 Semester 15. Human Rights 6 5 25 75 100 – IV [HIS4CC10] Credits-21 16. International 6 5 25 75 100 Relations [HIS4CC11] 17. Environmental 6 5 25 75 100 History [HIS4CC12 ] 18. -

Present Position Previous Positions Other Employment Degree

Dr. E. Thenral Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies Cellphone : 9952769574 e-Mail ID : [email protected] Address : B4, Second Floor, Kriti Flats Old No. 3/2, New No. 7, Abdul Razak 1st Street Saidapet Chennai - 600015 Present Position Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies, College of Engineering Guindy, Anna University, Chennai from August-2006. Previous Positions Lecturer, Department of Management Studies, College of Engineering Guindy, Anna University, Chennai during February-2005 and July-2006. Other Employment Management Trainee, Thesys Technologies Pvt Ltd for 0.7 years. Degree in PGP in Management, Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore (2001 - 2003). B.E. in INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING , CEG, Anna University (1996 - 2000). Research Degree Ph.D. in Management from Faculty of Management Sciences, College of Engineering, Guindy, Anna University (2010 - 2020). Title: Relationship Among the Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Value in Co-designed Products. Area of Specialisation Operations Marketing Research Guidance Number of M.E./ M.Tech. Projects : 140 page 1 / 3 Dr. E. Thenral Assistant Professor, Department of Management Studies Guided Papers Published in Journals Research Papers Published in International Journals : 1 Research Papers Published in National Journals : 0 1. E. Thenral and L. Suganthi, "Product Involvement and Self-efficacy on Perceived Value of Co-design", The Anthropologist, published by KRE Publishers. Vol. 34, Issue 1, pp. 20-27 (2018). Programme Attended 1. Attended a National level Short Course on "Orientation Training Programme on Re-engineering Teaching Skills" organized by Centre for Faculty Development, Anna University from 03-May-2005 to 05-May-2005. 2. Participated in a National level workshop on "Basic Econometrics" organized by IIT Madras from 20-Mar-2007 to 21-Mar-2007.