Coining Words Language and Politics in Late Colonial Tamilnadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Respect Movement Under Periyar

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 SELF RESPECT MOVEMENT UNDER PERIYAR M. Nala Assistant Professor of History Sri Sarada College for Women (Autonomous), Salem- 16 Self Respect Movement represented the Dravidian reaction against the Aryan domination in the Southern Society. It also armed at liberating the society from the evils of religious, customs and caste system. They tried to give equal status to the downtrodden and give the social dignity, Self Respect Movement was directed by the Dravidian communities against the Brahmanas. The movement wanted a new cultural society more based on reason rather than tradition. It aimed at giving respect to the instead of to a Brahmin. By the 19th Century Tamil renaissance gained strength because of the new interest in the study of the classical culture. The European scholars like Caldwell Beschi and Pope took a leading part in promoting this trend. C.V. Meenakshi Sundaram and Swaminatha Iyer through their wirtings and discourse contributed to the ancient glory of the Tamil. The resourceful poem of Bharathidasan, a disciple of Subramania Bharati noted for their style, beauty and force. C.N. Annadurai popularized a prose style noted for its symphony. These scholars did much revolutionise the thinking of the people and liberate Tamil language from brahminical influence. Thus they tried resist alien influence especially Aryan Sanskrit and to create a new order. The chief grievance of the Dravidian communities was their failure to obtain a fair share in the administration. Among then only the caste Hindus received education in the schools and colleges, founded by the British and the Christian missionaries many became servants of the Government, of these many were Brahmins. -

Page BRAHMANISM, BRAHMINS and BRAHMIN TAMIL in the CONTEXT of SPEECH to TEXT TECHNOLOGY Corresponding Email:[email protected]

BRAHMANISM, BRAHMINS AND BRAHMIN TAMIL IN THE CONTEXT OF SPEECH TO TEXT TECHNOLOGY R S Vignesh Raja, Ashik Alib Dr. BabakKhazaeic aResearch degree student, cSenior Lecturer Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom bSoftware Developer Fireflyapps Limited, Sheffield, United Kingdom Corresponding email:[email protected] Abstract Brahmanism in today's world is largely viewed as a 'caste' within Hinduism than its predecessor religion. This research paper explores the impact and influence religious affiliation could have on using certain advanced technologies such as the voice-to-text. This research paper attempts to reintroduce Brahmanism as a distinct religion and justifies through an empirical study and other literature as to why it is important, more specifically in language-related technology. Keywords: Tamil; speech to text; technology; Brahmanism; Brahmins 1. Introduction Speech-to-text is a fascinating area of research. The speech-to-text system exists for popular languages such as English. Whilst dealing with the user acceptance of technology, previous experiments suggest that it is vital to consider the religious affiliation as it could influence 'pronunciation' which is perceived to be very important for the users to be able to use voice-to- text technology in syllabic languages such as Tamil (Rama et al., 2002). Some of the previous experiments have identified the effect of code mixing, mispronunciation or in some cases the inability to correctly pronounce a syllable by the native Tamil speakers (Raj, Ali&Khazaei, 2015). This research paper aims to look into the code mixing and pronunciation aspects of 'Brahmin Tamil'- a dialect of Tamil spoken by the Brahmins who speak Tamil as their mother tongue. -

The Dravidian Languages

THE DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES BHADRIRAJU KRISHNAMURTI The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Bhadriraju Krishnamurti 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Times New Roman 9/13 pt System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0521 77111 0hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page xi List of tables xii Preface xv Acknowledgements xviii Note on transliteration and symbols xx List of abbreviations xxiii 1 Introduction 1.1 The name Dravidian 1 1.2 Dravidians: prehistory and culture 2 1.3 The Dravidian languages as a family 16 1.4 Names of languages, geographical distribution and demographic details 19 1.5 Typological features of the Dravidian languages 27 1.6 Dravidian studies, past and present 30 1.7 Dravidian and Indo-Aryan 35 1.8 Affinity between Dravidian and languages outside India 43 2 Phonology: descriptive 2.1 Introduction 48 2.2 Vowels 49 2.3 Consonants 52 2.4 Suprasegmental features 58 2.5 Sandhi or morphophonemics 60 Appendix. Phonemic inventories of individual languages 61 3 The writing systems of the major literary languages 3.1 Origins 78 3.2 Telugu–Kannada. -

Top 300 Masters 2020

TOP 300 MASTERS 2020 2020 Top 300 MASTERS 1 About Broadcom MASTERS Broadcom MASTERS® (Math, Applied Science, Technology and Engineering for Rising Stars), a program of Society for Science & the Public, is the premier middle school science and engineering fair competition, inspiring the next generation of scientists, engineers and innovators who will solve the grand challenges of the 21st century and beyond. We believe middle school is a critical time when young people identify their personal passion, and if they discover an interest in STEM, they can be inspired to follow their passion by taking STEM courses in high school. Broadcom MASTERS is the only middle school STEM competition that leverages Society- affiliated science fairs as a critical component of the STEM talent pipeline. In 2020, all 6th, 7th, and 8th grade students around the country who were registered for their local or state Broadcom MASTERS affiliated fair were eligible to compete. After submitting the online application, the Top 300 MASTERS are selected by a panel of scientists, engineers, and educators from around the nation. The Top 300 MASTERS are honored for their work with a $125 cash prize, through the Society’s partnership with the U.S. Department of Defense as a member of the Defense STEM education Consortium (DSEC). Top 300 MASTERS also receive a prize package that includes an award ribbon, a Top 300 MASTERS certificate of accomplishment, a Broadcom MASTERS backpack, a Broadcom MASTERS decal, a one-year family digital subscription to Science News magazine, an Inventor's Notebook, courtesy of The Lemelson Foundation, a one-year subscription to Wolfram Mathematica software, courtesy of Wolfram Research, and a special prize from Jeff Glassman, CEO of Covington Capital Management. -

GRAMMAR of OLD TAMIL for STUDENTS 1 St Edition Eva Wilden

GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1 st Edition Eva Wilden To cite this version: Eva Wilden. GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1 st Edition. Eva Wilden. Institut français de Pondichéry; École française d’Extrême-Orient, 137, 2018, Collection Indologie. halshs- 01892342v2 HAL Id: halshs-01892342 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01892342v2 Submitted on 24 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GRAMMAR OF OLD TAMIL FOR STUDENTS 1st Edition L’Institut Français de Pondichéry (IFP), UMIFRE 21 CNRS-MAE, est un établissement à autonomie financière sous la double tutelle du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (MAE) et du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). Il est partie intégrante du réseau des 27 centres de recherche de ce Ministère. Avec le Centre de Sciences Humaines (CSH) à New Delhi, il forme l’USR 3330 du CNRS « Savoirs et Mondes Indiens ». Il remplit des missions de recherche, d’expertise et de formation en Sciences Humaines et Sociales et en Écologie dans le Sud et le Sud- est asiatiques. Il s’intéresse particulièrement aux savoirs et patrimoines culturels indiens (langue et littérature sanskrites, histoire des religions, études tamoules…), aux dynamiques sociales contemporaines, et aux ecosystèmes naturels de l’Inde du Sud. -

Agastya International Foundation Synopsys

In Partnership with Student Projects Technical Record Released on the occasion of Science & Engineering Fair of Selected Projects at Shikshakara Sadana, K G Road Bangalore on th th th 26 , 27 & 28 February 2018 Organised by Agastya International Foundation In support with Synopsys Anveshana 2017-18- BANGALORE - Abstract Book Page 1 of 209 CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD 2. ABOUT AGASTYA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION 3. ABOUT SYNOPSYS 4. ABOUT ANVESHANA 5. PROJECT SCREENING COMMITTEE 6. COPY OF INVITATION 7. PROGRAM CHART 8. LIST OF PROJECTS EXHIBITED IN THE FAIR 9. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Anveshana 2017-18- BANGALORE - Abstract Book Page 2 of 209 FOREWORD In a world where recent events suggest that we may be entering a period of greater uncertainties, it is disturbing that India's educational system is not (in general) internationally competitive. In an age where the state of the economy is driven more and more by knowledge and skill, it is clear that the future of our country will depend crucially on education at all levels – from elementary schools to research universities. It is equally clear that the question is not one of talent or innate abilities of our country men, as more and more Indians begin to win top jobs in US business and industry, government and academia. Indian talent is almost universally acknowledged, as demonstrated by the multiplying number of R&D centres being set up in India by an increasing number of multinational companies. So what is the real problem? There are many problems ranging from poor talent management to an inadequate teaching system in most schools and colleges where there is little effort to make contact with the real world in general rather than only prescribed text books. -

Police Matters: the Everyday State and Caste Politics in South India, 1900�1975 � by Radha Kumar

PolICe atter P olice M a tte rs T he v eryday tate and aste Politics in South India, 1900–1975 • R a dha Kumar Cornell unIerIt Pre IthaCa an lonon Copyright 2021 by Cornell University The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https:creativecommons.orglicensesby-nc-nd4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New ork 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2021 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kumar, Radha, 1981 author. Title: Police matters: the everyday state and caste politics in south India, 19001975 by Radha Kumar. Description: Ithaca New ork: Cornell University Press, 2021 Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021005664 (print) LCCN 2021005665 (ebook) ISBN 9781501761065 (paperback) ISBN 9781501760860 (pdf) ISBN 9781501760877 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Police—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Law enforcement—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste— Political aspects—India—Tamil Nadu—History. Police-community relations—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste-based discrimination—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HV8249.T3 K86 2021 (print) LCC HV8249.T3 (ebook) DDC 363.20954820904—dc23 LC record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005664 LC ebook record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005665 Cover image: The Car en Route, Srivilliputtur, c. 1935. The British Library Board, Carleston Collection: Album of Snapshot Views in South India, Photo 6281 (40). -

Between Convergence and Divergence: Reformatting Language Purism in the Montreal Tamil Diasporas

Sonia Neela Das UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Between Convergence and Divergence: Reformatting Language Purism in the Montreal Tamil Diasporas This article examines how ideologies of language purism are reformatted by creating inter- discursive links across spatial and temporal scales. I trace convergences and divergences between South Asian and Québécois sociohistorical regimes of language purism as they pertain to the contemporary experiences of Montreal’s Tamil diasporas. Indian Tamils and Sri Lankan Tamils in Montreal emphasize their status differences by claiming that the former speak a modern “vernacular” Tamil and the latter speak an ancient “literary” Tamil. The segregation and purification of these social groups and languages depend upon the intergen- erational reproduction of scalar boundaries between linguistic forms, interlocutors, and decentered contexts. [Tamils, Quebec, diaspora, linguistic purism, spatiotemporal scales] ontreal is situated within the Canadian province of Quebec, a self- identifying francophone nation that seeks to be recognized as a “distinct Msociety” within North America1 (Lemco 1994). This society’s ever-present fear of being engulfed by a demographically expanding, English-speaking populace has contributed to a heightened level of metalinguistic awareness among French- speaking Québécois citizens. For the residents of Montreal, this metalinguistic aware- ness appears to be even more acute. Often characterized by scholars, politicians, and media as an inassimilable, globalizing element located within the otherwise -

Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges

DOI: 10.7763/IPEDR. 2012. V48. 17 Identity and Language of Tamil Community in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges + + + M. Rajantheran1 , Balakrishnan Muniapan2 and G. Manickam Govindaraju3 1Indian Studies Department, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Swinburne University of Technology, Sarawak, Malaysia 3School of Communication, Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia Abstract. Malaysia’s ruling party came under scrutiny in the 2008 general election for the inability to resolve pressing issues confronted by the minority Malaysian Indian community. Some of the issues include unequal distribution of income, religion, education as well as unequal job opportunity. The ruling party’s affirmation came under critical situation again when the ruling government decided against recognising Tamil language as a subject for the major examination (SPM) in Malaysia. This move drew dissatisfaction among Indians, especially the Tamil community because it is considered as a move to destroy the identity of Tamils. Utilising social theory, this paper looks into the fundamentals of the language and the repercussion of this move by Malaysian government and the effect to the Malaysian Indians identity. Keywords: Identity, Tamil, Education, Marginalisation. 1. Introduction Concepts of identity and community had been long debated in the arena of sociology, anthropology and social philosophy. Every community has distinctive identities that are based upon values, attitudes, beliefs and norms. All identities emerge within a system of social relations and representations (Guibernau, 2007). Identity of a community is largely related to the race it represents. Race matters because it is one of the ways to distinguish and segregate people besides being a heated political matter (Higginbotham, 2006). -

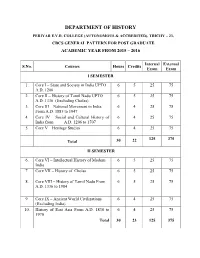

Department of History Periyar E.V.R

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY PERIYAR E.V.R. COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS & ACCREDITED), TRICHY – 23, CBCS GENERAL PATTERN FOR POST GRADUATE ACADEMIC YEAR FROM 2015 – 2016 Internal External S.No. Courses Hours Credits Exam Exam I SEMESTER 1. Core I – State and Society in India UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1206 2. Core II – History of Tamil Nadu UPTO 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 (Excluding Cholas) 3. Core III – National Movement in India 6 4 25 75 From A.D. 1885 to 1947 4. Core IV – Social and Cultural History of 6 4 25 75 India from A.D. 1206 to 1707 5. Core V – Heritage Studies 6 4 25 75 125 375 Total 30 22 II SEMESTER 6. Core VI – Intellectual History of Modern 6 5 25 75 India 7. Core VII – History of Cholas 6 5 25 75 8. Core VIII – History of Tamil Nadu From 6 5 25 75 A.D. 1336 to 1984 9. Core IX – Ancient World Civilizations 6 4 25 75 (Excluding India) 10. History of East Asia From A.D. 1830 to 6 4 25 75 1970 Total 30 23 125 375 III SEMESTER 11. Core XI – History of Political Thought 6 5 25 75 12. Core XII – Historiography 6 5 25 75 13. Core XIII – Socio - Economic and 6 5 25 75 Cultural History of India From A.D. 1707 to 1947 14. Core Based Elective - I: Contemporary 6 4 25 75 Issues in India 15. Core Based Elective - II: Dravidian 6 4 25 75 Movement Total 30 23 125 375 IV SEMESTER 16. -

Women's Roles and Participation in Rituals in the Maintenance of Cultural Identity: a Study of the Malaysian Iyers

SEARCH: The Journal of the South East Asia Research centre ISSN 2229-872X for Communications and Humanities. Vol. 7 No. 1, 2015, pp 1-21 Women’s Roles and Participation in Rituals in the Maintenance of Cultural Identity: A Study of the Malaysian Iyers Lokasundari Vijaya Sankar Taylor’s University, Malaysia © The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access by Taylor’s Press. ABSTRACT This paper examines the roles and rituals practiced by Malaysian Iyer women. The Iyers are a small community of Tamil Brahmins who live and work mainly in the Klang Valley. As an Indian diasporic community, who moved to Malaysia from the early 1900s, they have been slowly shifting from Tamil to English and Malay. They are upwardly mobile and place great emphasis on education but at the same time, value their traditions and culture. Data was derived from interactions between women and men from the Malaysian Iyer community together with personal observations made during visits to their homes, weddings and prayer sessions. This data was studied to obtain insights into cultural elements that ruled their discourse. The findings show that for this diasporic community that was slowly losing its language, ethnic identity can still be found in their cultural practices. Women were seen as keepers of tradition and customs that are important to the community. They followed certain cultural and traditional practices in their homes: practiced vegetarianism while cooking and serving food in their homes, followed taboos regarding food preparation, maintained patriarchal practices especially in religious practices and lived in extended families which usually included paternal grandparents. -

Inspiring Songs on Women Empowerment by Mahakavi Subramania Bharati

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 10, Ver. 11 (October.2016) PP 24-28 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Inspiring Songs on Women Empowerment by Mahakavi Subramania Bharati Shobha Ramesh Carnatic Classical Musician, All India Radio Artist and Performer,B.Ed,M.Phil,Cultural Studies and Music,Jain University,Bangalore,India Abstract:-In early India, in the name of tradition, men had for long suppressed women and had deprived them of their rightful place in society. Even in the mid-nineteenth century, women had absolutely negligible rights in Indian society and had to be subjugated to their husbands and others in society.Literacy among women was not given any importance in Indian society as a woman’s role as a male caretaker, wife or mother only took precedence. Even today, in many remote villages and very conservative households, women are supposed to cover their heads with the ‘pallu’(one portion) of their saris (the traditional attire of women in India)in the presence of elders and are not allowed to voice their opinions freely or even express their desires freely in their household. This great Indian freedom fighter and poet Mahakavi Subramania Bharati brought to light the oppression against women in the male-dominated Indian society through his awe-inspiring songs on women empowerment wherein he envisaged a new strong woman of the future, who he termed as a ‘new-age woman’. He envisaged the new-age woman as one who brakes free from all the chains that bind her to customs,traditions and age-old beliefs, as one who marches ahead confidently to find an identity of her own, one who walks hand in hand with her male counterpart, equal to him in all walks of life Keywords: Women, male-domination, Mahakavi Subramania Bharati, new-age woman, empowerment I.