Community Inclusion & Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007-2008

Annual Report 2007-2008 Annual Report 2007-2008 In accordance with the provisions of the Cultural Heritage Act 2002, the Board of Directors of Heritage Malta herewith submits the Annual Report & Accounts for the fifteen months ended 31 st December 2008. It is to be noted that the financial year–end of the Agency was moved to the 31 st of December (previously 30 th September) so as to coincide with the accounting year-end of other Government agencies . i Table of Contents Heritage Malta Mission Statement Pg. 1 Chairman’s Statement . Pg. 2 CEO’s Statement Pg. 4 Board of Directors and Management Team Pg. 5 Capital, Rehabilitation and Maintenance Works Pg. 7 Interpretation, Events and Exhibitions Pg. 17 Research, Conservation and Collections Pg. 30 The Institute for Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage Pg. 48 Conservation Division Pg. 53 Appendices I List of Acquisitions Pg. 63 II Heritage Malta List of Exhibitions October 2007 – December 2008 Pg. 91 III Visitor Statistics Pg. 96 Heritage Malta Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements Heritage Malta Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements Pg. 100 ii List of Abbreviations AFM Armed Forces of Malta AMMM Association of Mediterranean Maritime Museums CHIMS Cultural Heritage Information Management System CMA Collections Management System EAFRD European Agricultural Regional Development Funds ERDF European Regional Development Funds EU European Union HM Heritage Malta ICMCH Institute of Conservation and Management of Cultural Heritage, Bighi MCAST Malta College -

October 2012 NUMBER 42 €3.00

October 2012 NUMBER 42 €3.00 NEWSPAPER POST Din l-Art Ħelwa is a non-governmental organisation whose objective is to safeguard the cultural heritage and natural environment of the nation. The Council Din l-Art Ħelwa functions as the National Trust of Malta, restoring cultural heritage sites on behalf of the State, the Church, and private owners and managing and maintaining those sites for the benefit of the general public. Founder President Judge Maurice Caruana Curran Din l-Art Ħelwa strives to awaken awareness of cultural heritage and environmental matters by a policy of public education and by highlighting development issues to ensure that the highest possible standards are maintained and that local legislation is strictly enforced. THE COUNCIL 2011-13 Executive President Simone Mizzi Vice-Presidents Martin Scicluna Professor Luciano Mulé Stagno Hon. Secretary General George Camilleri Hon. Treasurer Victor Rizzo Members Professor Anthony Bonanno Albert Calleja Ian Camilleri The views expressed in Judge Maurice Caruana Curran VIGILO Cettina Caruana Curran are not necessarily Maria Grazia Cassar those of VIGILO Joseph F Chetcuti Din l-Art Ħelwa is published in April and October Carolyn Clements Josie Ellul Mercer VIGILO e-mail: Judge Joe Galea Debono Din l-Art Ħelwa [email protected] Martin Galea has reciprocal membership with: Cathy Farrugia The National Trust of England, COPYRIGHT by the PUBLISHER Dr Stanley Farrugia Randon Din l-Art Ħelwa Dame Blanche Martin Wales & Northern Ireland Dane Munro The National Trust for Scotland EDITOR Patricia Salomone DESIGN & LAYOUT Joanna Spiteri Staines The Barbados National Trust JOE AZZOPARDI Edward Xuereb PROOF READER The National Trust of Australia JUDITH FALZON The Gelderland Trust for PHOTOGRAPHS Historic Houses If not indicated otherwise photographs are by Din l-Art Ħelwa The Gelderland ‘Nature Trust’ JOE AZZOPARDI National Trust of Malta 133 Melita Street Din l-Art Ħelwa PRINTED BY is a member of: Best Print Co. -

Project Description Statement for a Proposed Fast Ferry Landing Site in Valletta

PA/00122/18 - 75a - Valid - Ryan Busuttil - on behalf of Environment and Resources Authority - 20/4/18 3:43:16 PM 75a Project Description Statement for a Proposed Fast Ferry Landing Site in Valletta as per ERA requirements for the Planning Permit (PA/00122/18) Technical Report AIS REF. NO: ENV332592/339 CLIENT REF. NO: PA/00122/18 FIRST VERSION Publication Date 13 April 2018 Page 1 of 55 PA/00122/18 - 75a - Valid - Ryan Busuttil - on behalf of Environment and Resources Authority - 20/4/18 3:43:16 PM 75a PDS FOR A PROPOSED FAST FERRY LANDING SITE IN VALLETTA DOCUMENT REVISION HISTORY Date Revision Comments Authors/Contributors 13/04/2018 1.0 First Version Siân Pledger Sacha Dunlop Ing Mario Schembri AMENDMENT RECORD Approval Level Name Signature Internal Check Sacha Dunlop Internal Approval Mario Schembri Page | i Page 2 of 55 PA/00122/18 - 75a - Valid - Ryan Busuttil - on behalf of Environment and Resources Authority - 20/4/18 3:43:16 PM 75a PDS FOR A PROPOSED FAST FERRY LANDING SITE IN VALLETTA DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by AIS Environment Limited with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, and taking account of the manpower and resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. Information reported herein is based on the interpretation of data collected and has been accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. This report is for the exclusive use of Transport Malta; no warranties or guarantees are expressed or should be inferred by any third parties. This report may not be relied upon by other parties without written consent from AIS Environment Limited. -

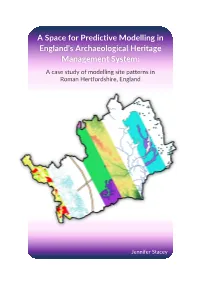

A Space for Predictive Modelling In

A Space for Predictive Modelling in England’s Archaeological Heritage Management System: A case study of modelling site patterns in Roman Hertfordshire, England Jennifer Stacey Figure 1: A collaboration of different data layers that were used to influence and create the Roman Hertfordshire predictive model. From left to right: land-use, modern roads, Roman roads, bedrock geology, digital elevation model, modern rivers, superficial bedrock, archaeological sites (Stacey 2020). E-mail: [email protected] 1 A Space for Predictive Modelling in England’s Archaeological Heritage Management System: A case study of modelling site patterns in Roman Hertfordshire, England Jennifer Stacey S1829424 MSc Thesis Archaeology (4ARX-0910ARCH) Supervisor: Dr. K. Lambers Specialisation: Archaeological Science University of Leiden, Faculty of Archaeology Leiden, 21/08/20 Final draft 2 Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Brief Introduction to Archaeological Predictive Modelling .......................... 7 1.2. The Motive for the Research ......................................................................... 8 1.3. Aims and Research Questions ....................................................................... 9 1.4. Thesis Outline .............................................................................................. 10 2. Hertfordshire and Archaeological Heritage Management (AHM) .......... 13 2.1. Characteristics of Hertfordshire -

Malta Painted by Vittorio Boron Described by Frederick W

MALTA PAINTED BY VITTORIO BORON DESCRIBED BY FREDERICK W. RYAN 488742 30. 3- LONDON ADAM & CHARLES BLACK 1910 TO COUNT GIROLAMO TAGLIAFERRO THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED BY THE WRITER PREFACE THE following text is intended to give no more than a slight sketch, aided by Signer Boron's effective pencil, of the manifold interests to be found in Malta. While the archaeology of the island and its con- nection with the Order of St. John of Jerusalem have from time to time attracted attention, English writers seem regrettably to have neglected other topics presented by this unique Imperial posses- sion, such as the folk-lore and literature of the the of the Maltese language ; growth early Christian of the nature of the ' Church Malta ; Consiglio Popolare' that gleam of constitutional govern- ment in the Dark Ages quite as interesting as the or the social Wittenagemote ; and economic condition of the Maltese people under the Knights and in the early days of British rule all of which have engaged the attention of Italian and Maltese historians. vi PREFACE Circumstances have not allowed more than a passing allusion in the following pages to such subjects : they are here mentioned to indicate the fruitful field of research embraced by the Malta Historical and Scientific Society, formed last year in Valletta, which proposes, under the guidance of its President, Professor Napoleon Tagliaferro, to * study the history and archaeology of the Maltese ' Islands and other scientific subjects of local interest an association well worthy of the support of British residents in Malta. The vast contents of the Record Office in Valletta and oral tradition the latter nowhere stronger than in these islands may on examination con- tribute many valuable additions to literature and history. -

Programm Kulturali Għall-2018

CULTURAL PROGRAMME 2018 IL-PROGRAMM KULTURALI 2018 VALLETTA 2018 EUROPEAN CAPITAL OF CULTURE THE YEAR 2018 USHERS IN AN EXCITING CELEBRATION ROOTED IN THE UNIQUE HERITAGE OF THE MALTESE ISLANDS. IS-SENA 2018 TAGĦTINA ĊELEBRAZZJONI EĊĊITANTI B’GĦERUQ FONDI FIL-PATRIMONJU UNIKU TAL-GŻEJJER MALTIN. 2018 Cultural Programme Introduction 002 \ 003 VALLETTA 2018 INVITES YOU TO TAKE PART IN AN ISLAND-WIDE FESTA, A 360-DEGREE EXPLORATION OF CONTEMPORARY MALTESE AND GOZITAN LIFE THAT DRAWS INSPIRATION FROM HOME WHILE LOOKING OUT TO OUR NEIGHBOURS ACROSS THE SEA. As per the Charter signed by all Local Councils in Malta and Gozo, Valletta’s title of European Capital of Culture 2018 is an award shared among all localities on our Islands. Further information can be found at valletta2018.org Skont il-Karta ffirmata mill-Kunsilli VALLETTA 2018 TISTIEDNEK TIPPARTEĊIPA F’FESTA Lokali kollha f’Malta u f’Għawdex, KBIRA MADWAR IL-GŻIRA KOLLHA, DAWRA it-titlu ta’ Kapitali Ewropea tal-Kultura 2018 mogħti lill-Belt Valletta huwa titlu TA’ 360-GRAD MADWAR IL-ĦAJJA MALTIJA U li jinqasam bejn il-lokalitajiet kollha GĦAWDXIJA KONTEMPORANJA LI TISPIRA RUĦHA tal-gżejjer tagħna. MILL-GŻEJJER TAGĦNA FILWAQT LI TĦARES LEJN Aktar informazzjoni tista’ tinkiseb minn: IL-ĠIRIEN TAGĦNA LIL HINN MINN XTUTNA. valletta2018.org VALLETTA 2018 EUROPEAN CAPITAL OF CULTURE CONTENTS // WERREJ A WORD FROM… // KELMA MINGĦAND… …OUR CHAIRMAN 006 // IĊ-ĊERMEN TAGĦNA …OUR PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARY 008 // IS-SEGRETARJU PARLAMENTARI TAGĦNA …OUR MINISTER FOR CULTURE 010 // IL-MINISTRU GĦALL-KULTURA -

National Museums in Malta Romina Delia

Building National Museums in Europe 1750-2010. Conference proceedings from EuNaMus, European National Museums: Identity Politics, the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen, Bologna 28-30 April 2011. Peter Aronsson & Gabriella Elgenius (eds) EuNaMus Report No 1. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.ep.liu.se/ecp_home/index.en.aspx?issue=064 © The Author. National Museums in Malta Romina Delia Summary In 1903, the British Governor of Malta appointed a committee with the purpose of establishing a National Museum in the capital. The first National Museum, called the Valletta Museum, was inaugurated on the 24th of May 1905. Malta gained independence from the British in 1964 and became a Republic in 1974. The urge to display the island’s history, identity and its wealth of material cultural heritage was strongly felt and from the 1970s onwards several other Museums opened their doors to the public. This paper goes through the history of National Museums in Malta, from the earliest known collections open to the public in the seventeenth century, up until today. Various personalities over the years contributed to the setting up of National Museums and these will be highlighted later on in this paper. Their enlightened curatorship contributed significantly towards the island’s search for its identity. Different landmarks in Malta’s historical timeline, especially the turbulent and confrontational political history that has marked Malta’s colonial experience, have also been highlighted. The suppression of all forms of civil government after 1811 had led to a gradual growth of two opposing political factions, involving a Nationalist and an Imperialist party. -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Capital Works 1.1 National Funds 3 1.2 National Monuments 8 1.3 EU Co-Funded Projects 9 2. Exhibitions and Events 14 3. Collections and Research 17 4. Conservation 4.1 Paintings, Polychrome Sculpture and Wood Sculpture 27 4.2 Stone, Ceramics, Metal and Glass 29 4.3 Textiles, Books and Paper 30 4.4 Diagnostic Sciences Laboratories 31 5. Education, Publications and Outreach 5.1 Thematic Events and Hands-on Sessions 32 5.2 Publications 37 6. Other Corporate 39 7. Visitor Statistics and Analysis 7.1 Admissions 42 7.2 Statistical Analysis 43 8. Appendix 1 – Calendar of Events 8.1 Exhibitions Hosted by HM 54 8.2 Exhibitions Organised by HM 54 8.3 Exhibitions in Collaboration with Others 55 8.4 Exhibitions in which HM Participated 56 8.5 Lectures Organised/Hosted by HM 57 8.6 Events Organised by HM 58 8.7 Events in HM Participated 64 8.8 Organised in Collaboration with Others 65 8.9 Events Hosted by HM 68 9. Appendix 2 – Purchase of Modern and Contemporary Artworks 71 10. Appendix 3 – Acquisition of Natural History Specimens 72 11. Appendix 4 – Acquisition of Cultural Heritage Objects 73 2 1. CAPITAL WORKS 1.1 NATIONAL FUNDS During the year under review design for improvements to the layout in the ticketing and shop area of the Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra visitor centre was concluded and manufacture of furniture started. Such works will include the construction of a site office, new ticketing facilities and new larger shop within the existing building in order to maximize shop space and visitor flow. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 5 Capital Works 7 Exhibitions and Events 15 Collections and Research 21 Conservation 35 Education, Publications and Outreach 45 Other Corporate 49 Visitor Statistics 53 Appendix 1 – Calendar of Events 69 Appendix 2 – Purchase of Modern and Contemporary Artworks 89 Appendix 3 – Acquisition of Natural History Specimens 91 Appendix 4 – Purchase of Items for Gozo Museum 93 Appendix 5 – Acquisition of Cultural Heritage Items 95 3 Foreword During the year under review Heritage Malta sustained the positive impetus and to some extent surpassed the noteworthy and record breaking achievements of 2017. This year (2018) marked the year where Valletta was nominated as the European Capital of Culture. This not only presented a challenge in terms of value adding initiatives undertook by the Agency, but also meant a positive influx of tourists in Malta visiting museums and sites managed by Heritage Malta. Besides the inauguration of MUZA as a major ERDF co-funded project, the agency also worked in parallel on two other major ERDF co-funded projects, organized popular exhibitions and participated in important exhibitions abroad. Heritage Malta also increased the number of heritage sites under its responsibility, and managed to register a record in the number of visitor and generation of revenue for the sixth year in a row. The Agency also launched the popular Heritage Malta Passport Scheme for all students (primary and secondary) to benefit from unlimited free entry to all museums and sites accompanied by two adults. An initiative promoting accessibility to Malta’s cultural heritage! The Agency’s output comprised also the biggest-ever number of cultural activities, website hits and social media statistics, and an impressive outreach programme including thematic sessions for school children and publications. -

Heritage Under Water at Risk

HERITAGE AT RISK SPECIAL EDITION HERITAGE UNDER WATER AT RISK THREATS – CHALLENGES – SOLUTIONS HERITAGE AT RISK SPECIAL EDITION HERITAGE UNDER WATER AT RISK THREATS – CHALLENGES – SOLUTIONS ~ LE PATRIMOINE SOUS L‘EAU EN PERIL MENACES – DÉFIS – SOLUTIONS ~ PATRIMONIO BAJO EL AGUA EN PELIGRO AMENAZAS – DESAFÍOS – SOLUCIONES ~ EDITED BY ALBERT HAFNER – HAKAN ÖNIZ – LUCY SEMAAN – CHRISTOPHER J. UNDERWOOD PUBLISHED BY THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON MONUMENTS AND SITES (ICOMOS) INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE ON THE UNDERWATER CULTURAL HERITAGE (ICUCH) 4 Impressum IMPRESSUM Heritage Under Water at Risk: Challenges, Threats and Solutions Edited by Albert Hafner – Hakan Öniz – Lucy Semaan – Christopher J. Underwood Published by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) International Committee on the Underwater Cultural Heritage (ICUCH) President: Mr Toshiyuki Kono (Japan) Secretary General: Mr Peter Phillips (Australia) international council on monuments and sites Treasurer General: Ms Laura Robinson (South Africa) Vice Presidents: Mr Leonardo Castriota (Brazil) Mr Alpha Diop (Mali) Mr Rohit Jigyasu (India) Mr Grellan Rourke (Ireland) Mr Mario Santana Quintero (Canada) International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) Office: 11 Rue du Séminaire de Conflans, 94220 Charenton-le-Pont, Paris, France Editorial support, layout and design Amelie Alterauge, Susanna Kaufmann and Andrea Bieri, Institute of Archaeological Sciences, University of Bern, Switzerland. The production of this publication was substantially supported by the University of Bern. © November 2020 ICOMOS ISBN 978-2-918086-37-6 eISBN 978-2-918086-38-3 Front Cover: A cargo of roof tiles from a shipwreck from Catal Island/Kalkan in Antalya, Turkey. © Hakan Öniz. Inside Front Cover: Platform for diving and drilling cores at Plocha Michov Grad, Lake Ohrid, North Macedonia. -

Urban Planning and Archeological Conscience: the Impact of Soil Sealing on Archaeological Sites

Urban planning and archeological conscience: The impact of soil sealing on archaeological sites Planificación urbana y conciencia arqueológica: Impacto del sellado del suelo en yacimientos arqueológicos AUTHORS Planeamento urbano e consciência arqueológica: Impacto da impermeabilização do solo em sítios arqueológicos García Rodríguez @ 11 M.P.@, 1 [email protected] Received: 26.10.2016 Revised: 17.02.2017 Accepted: 08.03.2017 Álvarez García B. 2 ABSTRACT Soil sealing (permanent covering of an area by impermeable artificial material) is one of the most serious problems affecting ecosystems in Western Europe. Numerous studies have analysed this issue @ Corresponding Author from an ecological approach, but very few take into account its impact on one of soil’s essential 1 Dpto. Análisis functions, namely the preservation of archaeological sites. Spanish laws on historic heritage (1985) Geográfico Regional and environmental impact (2013) have tackled the matter by legislating measures for the preservation y Geografía Física. of heritage. Furthermore, in 1992 Spain signed the Valletta Treaty (the European Convention on the Facultad de Geografía e Historia. Universidad Protection of the Archaeological Heritage) of the Council of Europe, and further ratified it in 2011. Complutense de Madrid. Historians, archaeologists and soil scientists should respond to this threat using a multidisciplinary C/Prof. Aranguren, s/n. approach. The present study analyses the impact that soil sealing has had on the Roman city of 28040 Madrid, Spain. Complutum, located on the Henares River plain (Madrid, España) on highly fertile Fluvisols and 2 Dpto. Historia Moderna. Calcisols. One of the aims of this study is to show that the combined use of aerial photos and satellite Facultad de Geografía images provides a continuously updated file of urban development processes and therefore makes it e Historia. -

History of Malta Under the Order of Saint John - Wikipedia

6/23/2020 History of Malta under the Order of Saint John - Wikipedia History of Malta under the Order of Saint John Malta was ruled by the Order of Saint John as a vassal state of the Kingdom of Sicily from 1530 to 1798. The islands of Malta Malta and Gozo, as well as the city of Tripoli in modern Libya, were Order of Saint John of granted to the Order by Spanish Emperor Charles V in 1530, Jerusalem following the loss of Rhodes. The Ottoman Empire managed to Ordine di San Giovanni di capture Tripoli from the Order in 1551, but an attempt to take Gerusalemme (in Italian) Malta in 1565 failed. Ordni ta' San Ġwann ta' Following the 1565 siege, the Order decided to settle Ġerusalemm (in Maltese) permanently in Malta and began to construct a new capital city, 1530–1798 Valletta. For the next two centuries, Malta went through a Golden Age, characterized by a flourishing of the arts, architecture, and an overall improvement in Maltese society.[2] In the mid-17th century, the Order was the de jure proprietor over some islands in the Caribbean, making it the smallest state to colonize the Americas.. Flag The Order began to decline in the 1770s, and was severely Coat of arms weakened by the French Revolution in 1792. In 1798, French forces under Napoleon invaded Malta and expelled the Order, resulting in the French occupation of Malta. The Maltese eventually rebelled against the French, and the islands became a British protectorate in 1800. Malta was to be returned to the Order by the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, but the British remained in control and the islands formally became a British colony by the Treaty of Paris in 1814.