Bound Variables and Other Anaphors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions Under Discussion: from Sentence to Discourse∗

Questions under Discussion: From sentence to discourse∗ Anton Benz Katja Jasinskaja July 14, 2016 Abstract Questions under discussion (QUD) is an analytic tool that has recently become more and more popular among linguists and language philosophers as a way to characterize how a sentence fits in its context. The idea is that each sentence in discourse addresses a (of- ten implicit) QUD either by answering it, or by bringing up another question that can help answering that QUD. The linguistic form and the interpretation of a sentence, in turn, may depend on the QUD it addresses. The first proponents of the QUD approach (von Stut- terheim & Klein, 1989; van Kuppevelt, 1995) thought of it as a general approach to the analysis of discourse structure where structural relations between sentences in a coherent discourse are understood in terms of relations between questions they address. However, the idea did not find broad application in discourse structure analysis, where theories aiming at logical discourse representations are predominantly based on the notion of coherence re- lations (Mann & Thompson, 1988; Hobbs, 1985; Asher & Lascarides, 2003). The problem of finding overt markers for QUDs means that they are also difficult to utilize for quanti- tative measures of discourse coherence (McNamara et al., 2010). At the same time QUD proved useful in the analysis of a wide range of linguistic phenomena including accentua- tion, discourse particles, presuppositions and implicatures. The goal of this special issue is to bring together cutting-edge research that demonstrates the success of QUD in linguistics and the need for the development of a comprehensive model of discourse coherence that incorporates the notion of QUD as its integral part. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

VP Ellipsis Without Parallel Binding∗

Proceedings of SALT 24: 000–000, 2014 The sticky reading: VP ellipsis without parallel binding∗ Patrick D. Elliott Andreea C. Nicolae University College London ZAS Berlin Yasutada Sudo University College London Abstract VP Ellipsis (VPE) whose antecedent VP contains a pronoun famously gives rise to an ambiguity between strict and sloppy readings. Since Sag’s (1976) seminal work, it is generally assumed that the strict reading involves free pronouns in both the elided VP and its antecedent, whereas the sloppy reading involves bound pronouns. The majority of current approaches to VPE are tailored to derive this parallel binding requirement, ruling out mixed readings where one of the VPs involves a bound pronoun and the other a free pronoun in parallel positions. Contrary to this assumption, it is observed that there are cases of VPE where the antecedent VP contains a bound pronoun but the elided VP contains a free E-type pronoun anchored to the quantifier, in violation of parallel binding. We dub this the ‘sticky reading’ of VPE. To account for it, we propose a new identity condition on VPE which is less stringent than is standardly assumed. We formalize this using an extension of Roberts’s (2012) Question under Discussion (QuD) theory of information structure. Keywords: VP ellipsis, strict/sloppy identity, pronominal binding, focus, Question under Discussion 1 Introduction It has been famously observed by Sag(1976) that pronouns give rise to an ambiguity in a VP Ellipsis (VPE) context. An example such as (1) is claimed to be ambiguous between so-called strict and sloppy readings. (1) Jonny totaled his car, and Kevin did h...i too. -

Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, and Adverbs

Unit 1: The Parts of Speech Noun—a person, place, thing, or idea Name: Person: boy Kate mom Place: house Minnesota ocean Adverbs—describe verbs, adjectives, and other Thing: car desk phone adverbs Idea: freedom prejudice sadness --------------------------------------------------------------- Answers the questions how, when, where, and to Pronoun—a word that takes the place of a noun. what extent Instead of… Kate – she car – it Many words ending in “ly” are adverbs: quickly, smoothly, truly A few other pronouns: he, they, I, you, we, them, who, everyone, anybody, that, many, both, few A few other adverbs: yesterday, ever, rather, quite, earlier --------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------- Adjective—describes a noun or pronoun Prepositions—show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and another word in the sentence. Answers the questions what kind, which one, how They begin a prepositional phrase, which has a many, and how much noun or pronoun after it, called the object. Articles are a sub category of adjectives and include Think of the box (things you have do to a box). the following three words: a, an, the Some prepositions: over, under, on, from, of, at, old car (what kind) that car (which one) two cars (how many) through, in, next to, against, like --------------------------------------------------------------- Conjunctions—connecting words. --------------------------------------------------------------- Connect ideas and/or sentence parts. Verb—action, condition, or state of being FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) Action (things you can do)—think, run, jump, climb, eat, grow A few other conjunctions are found at the beginning of a sentence: however, while, since, because Linking (or helping)—am, is, are, was, were --------------------------------------------------------------- Interjections—show emotion. -

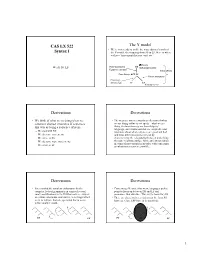

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals As Windows Into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer

University of Massachusetts Amherst From the SelectedWorks of Angelika Kratzer 2009 Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer Available at: https://works.bepress.com/angelika_kratzer/ 6/ Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns Angelika Kratzer This article argues that natural languages have two binding strategies that create two types of bound variable pronouns. Pronouns of the first type, which include local fake indexicals, reflexives, relative pronouns, and PRO, may be born with a ‘‘defective’’ feature set. They can ac- quire the features they are missing (if any) from verbal functional heads carrying standard -operators that bind them. Pronouns of the second type, which include long-distance fake indexicals, are born fully specified and receive their interpretations via context-shifting -operators (Cable 2005). Both binding strategies are freely available and not subject to syntactic constraints. Local anaphora emerges under the assumption that feature transmission and morphophonological spell-out are limited to small windows of operation, possibly the phases of Chomsky 2001. If pronouns can be born underspecified, we need an account of what the possible initial features of a pronoun can be and how it acquires the features it may be missing. The article develops such an account by deriving a space of possible paradigms for referen- tial and bound variable pronouns from the semantics of pronominal features. The result is a theory of pronouns that predicts the typology and individual characteristics of both referential and bound variable pronouns. Keywords: agreement, fake indexicals, local anaphora, long-distance anaphora, meaning of pronominal features, typology of pronouns 1 Fake Indexicals and Minimal Pronouns Referential and bound variable pronouns tend to look the same. -

Modeling Scope Ambiguity Resolution As Pragmatic Inference: Formalizing Differences in Child and Adult Behavior K.J

Modeling scope ambiguity resolution as pragmatic inference: Formalizing differences in child and adult behavior K.J. Savinelli, Gregory Scontras, and Lisa Pearl fksavinel, g.scontras, lpearlg @uci.edu University of California, Irvine Abstract order of these elements in the utterance (i.e., Every precedes n’t). In contrast, for the inverse scope interpretation in (1b), Investigations of scope ambiguity resolution suggest that child behavior differs from adult behavior, with children struggling this isomorphism does not hold, with the scope relationship to access inverse scope interpretations. For example, children (i.e., : scopes over 8) opposite the linear order of the ele- often fail to accept Every horse didn’t succeed to mean not all ments in the utterance. Musolino hypothesized that this lack the horses succeeded. Current accounts of children’s scope be- havior involve both pragmatic and processing factors. Inspired of isomorphism would make the inverse scope interpretation by these accounts, we use the Rational Speech Act framework more difficult to access. In line with this prediction, Conroy to articulate a formal model that yields a more precise, ex- et al. (2008) found that when adults are time-restricted, they planatory, and predictive description of the observed develop- mental behavior. favor the surface scope interpretation. We thus see a potential Keywords: Rational Speech Act model, pragmatics, process- role for processing factors in children’s inability to access the ing, language acquisition, ambiguity resolution, scope inverse scope. Perhaps children, with their still-developing processing abilities, can’t allocate sufficient processing re- Introduction sources to reliably access the inverse scope interpretation. If someone says “Every horse didn’t jump over the fence,” In addition to this processing factor, Gualmini et al. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Relative Clause Attachment and Anaphora: a Case for Short Binding

Relative Clause Attachment and Anaphora: A Case for Short Binding Rodolfo Delmonte Ca' Garzoni-Moro, San Marco 3417, Università "Ca Foscari", 30124 - VENEZIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Relative clause attachment may be triggered by binding requirements imposed by a short anaphor contained within the relative clause itself: in case more than one possible attachment site is available in the previous structure, and the relative clause itself is extraposed, a conflict may arise as to the appropriate s/c-structure which is licenced by grammatical constraints but fails when the binding module tries to satisfy the short anaphora local search for a bindee. 1 Introduction It is usually the case that anaphoric and pronominal binding take place after the structure building phase has been successfully completed. In this sense, c-structure and f-structure in the LFG framework - or s-structure in the chomskian one - are a prerequisite for the carrying out of binding processes. In addition, they only interact in a feeding relation since binding would not be possibly activated without a complete structure to search, and there is no possible reversal of interaction, from Binding back into s/c-structure level seen that they belong to two separate Modules of the Grammar. As such they contribute to each separate level of representation with separate rules, principles and constraints which need to be satisfied within each Module in order for the structure to be licensed for the following one. However we show that anaphoric binding requirements may cause the parser to fail because the structure is inadequate. We propose a solution to this conflict by anticipating, for anaphors only the though, the agreement matching operations between binder and bindee and leaving the coindexation to the following module. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(S): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol

MIT Press Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe Author(s): Hilda Koopman and Dominique Sportiche Source: Linguistic Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 555-588 Published by: MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178645 Accessed: 22-10-2015 18:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Linguistic Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.97.27.20 on Thu, 22 Oct 2015 18:32:27 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Hilda Koopman Pronouns, Logical Variables, Dominique Sportiche and Logophoricity in Abe 1. Introduction 1.1. Preliminaries In this article we describe and analyze the propertiesof the pronominalsystem of Abe, a Kwa language spoken in the Ivory Coast, which we view as part of the study of pronominalentities (that is, of possible pronominaltypes) and of pronominalsystems (that is, of the cooccurrence restrictionson pronominaltypes in a particulargrammar). Abe has two series of thirdperson pronouns. One type of pronoun(0-pronoun) has basically the same propertiesas pronouns in languageslike English. The other type of pronoun(n-pronoun) very roughly corresponds to what has been called the referential use of pronounsin English(see Evans (1980)).It is also used as what is called a logophoric pronoun-that is, a particularpronoun that occurs in special embedded contexts (the logophoric contexts) to indicate reference to "the person whose speech, thought or perceptions are reported" (Clements (1975)). -

Scope Ambiguity in Syntax and Semantics

Scope Ambiguity in Syntax and Semantics Ling324 Reading: Meaning and Grammar, pg. 142-157 Is Scope Ambiguity Semantically Real? (1) Everyone loves someone. a. Wide scope reading of universal quantifier: ∀x[person(x) →∃y[person(y) ∧ love(x,y)]] b. Wide scope reading of existential quantifier: ∃y[person(y) ∧∀x[person(x) → love(x,y)]] 1 Could one semantic representation handle both the readings? • ∃y∀x reading entails ∀x∃y reading. ∀x∃y describes a more general situation where everyone has someone who s/he loves, and ∃y∀x describes a more specific situation where everyone loves the same person. • Then, couldn’t we say that Everyone loves someone is associated with the semantic representation that describes the more general reading, and the more specific reading obtains under an appropriate context? That is, couldn’t we say that Everyone loves someone is not semantically ambiguous, and its only semantic representation is the following? ∀x[person(x) →∃y[person(y) ∧ love(x,y)]] • After all, this semantic representation reflects the syntax: In syntax, everyone c-commands someone. In semantics, everyone scopes over someone. 2 Arguments for Real Scope Ambiguity • The semantic representation with the scope of quantifiers reflecting the order in which quantifiers occur in a sentence does not always represent the most general reading. (2) a. There was a name tag near every plate. b. A guard is standing in front of every gate. c. A student guide took every visitor to two museums. • Could we stipulate that when interpreting a sentence, no matter which order the quantifiers occur, always assign wide scope to every and narrow scope to some, two, etc.? 3 Arguments for Real Scope Ambiguity (cont.) • But in a negative sentence, ¬∀x∃y reading entails ¬∃y∀x reading.