Download Issue (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Back 2 X 3.5" Ad the Series Revival of “Will & Grace” Premieres Thursday on NBC

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad September 22 - 28, 2017 We’ve got you covered! waxahachietx.com A M B E D N D A P S H E M D O 2 x 3" ad T X A L V O I C E C H O A U R Your Key A R R W G M O A R X Q I R P E To Buying M L B E E S Y A R E U M Y E H 2 x 3.5" ad S P E S C F H D Y M A X A Z E and Selling! A H R X I C U F E G I F T E D L P E R A W E S U Y N T P Y I B A R L A R X N W A W H A R X Q C A M D X P O T T S E R G O Z U E O F O V F A R G P S A E P E T T H S N A J O I H O L B M W O E N C X M A X A C N U M G E X I X V U I A K T E S W G E F W J C A K L G E O R G E V O T U V C K S Y I X B I V A H “Young Sheldon” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Sheldon (Iain) Armitage (East) Texas Place your classified Solution on page 13 Mary (Zoe) Perry Gifted ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad George (Sr.) (Lance) Barber Eccentric Light, Midlothian Mirror and ‘Will & Grace’ 1 x 4" ad Meemaw (Annie) Potts Twins Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Voice (of Sheldon) (Jim) Parsons Family Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it is back 2 x 3.5" ad The series revival of “Will & Grace” premieres Thursday on NBC. -

Date Headline URL Hit Sentence Source

Date Headline URL Hit Sentence Source http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2018/03/despite_clotilda_disa 09-Mar-2018 03:17PM Despite Clotilda disappointment, Africatown hopes high ppointmen.html AL.com Historical Commission says the ship is too new and too Alabama Wreck Isn't The Remains Of The Slave Ship http://www.topix.com/state/al/2018/03/alabama-wreck-isnt-the- large to be the Clotilda, which was the last known vessel 08-Mar-2018 07:29AM Clotilda remains-of-the-slave-ship-clotilda to bring enslaved people to Topix http://buffalonews.com/2018/03/07/noreaster-winds-reveal-a- Nor'easter winds reveal surprising beach discovery: surprising-beach-discovery-the-remains-of-a-revolutionary-war-era- 07-Mar-2018 01:55PM Remains of Revolutionary War-era ship ship/ The Buffalo News Their research sparked an all-out investigation by the Alabama Shipwreck Turns Out Not to be the Clotilda, the http://atlantablackstar.com/2018/03/07/alabama-shipwreck-turns- Alabama Historical Commission and international 07-Mar-2018 12:36PM Last American Slave Ship not-clotilda-last-american-slave-ship/ partners of the Slave Wrecks Project, Atlanta Black Star 07-Mar-2018 12:12PM The Gadfly: March 7, 2018 https://lagniappemobile.com/the-gadfly-march-7-2018/ Lagniappe Mobile site. The discovery also set in motion activity by the Alabama Historical Commission, visits from the Slave 07-Mar-2018 10:35AM Ship hits the fan? Not so, Raines says https://lagniappemobile.com/ship-hits-the-fan-not-so-raines-says/ Wrecks Project and Diving with a Lagniappe Mobile 07-Mar-2018 10:35AM -

2011 State of the News Media Report

Overview By Tom Rosenstiel and Amy Mitchell of the Project for Excellence in Journalism By several measures, the state of the American news media improved in 2010. After two dreadful years, most sectors of the industry saw revenue begin to recover. With some notable exceptions, cutbacks in newsrooms eased. And while still more talk than action, some experiments with new revenue models began to show signs of blossoming. Among the major sectors, only newspapers suffered continued revenue declines last year—an unmistakable sign that the structural economic problems facing newspapers are more severe than those of other media. When the final tallies are in, we estimate 1,000 to 1,500 more newsroom jobs will have been lost—meaning newspaper newsrooms are 30% smaller than in 2000. Beneath all this, however, a more fundamental challenge to journalism became clearer in the last year. The biggest issue ahead may not be lack of audience or even lack of new revenue experiments. It may be that in the digital realm the news industry is no longer in control of its own future. News organizations — old and new — still produce most of the content audiences consume. But each technological advance has added a new layer of complexity—and a new set of players—in connecting that content to consumers and advertisers. In the digital space, the organizations that produce the news increasingly rely on independent networks to sell their ads. They depend on aggregators (such as Google) and social networks (such as Facebook) to bring them a substantial portion of their audience. And now, as news consumption becomes more mobile, news companies must follow the rules of device makers (such as Apple) and software developers (Google again) to deliver their content. -

Glorydaysofpaul Boesch's

HoustonChronicleLife&Entertainment Houston Chronicle | Sunday, July 19,2015 |HoustonChronicle.com and Chron.com @HoustonChron Section G 777 ZEST ‘MotownIt’s allabout the music in’ Joan Marcus Krisha Marcano,fromleft,Allison Semmes and Trisha Jeffrey star in first national tour of “Motown, The Musical.” INSIDE TwoHoustonians star in the ensembletouring production By Joey Guerra Jr.Both grewuphere and have been What do these with the tour since it kickedofflast HSPVA grads Motown —the label, the music, year. the movement—made superstars “Every time we do this show, miss about out of Diana Ross, Smokey Robinson there’s something Ilearn about the Houston? and MichaelJackson. TwoHouston powerofMotown —the artists, Ashley Támar Davis: nativesare hoping “Motown: The the songwriters, from the secretar- Family, home cooking Musical”will put them on the map, ies to Mr.Gordy,”Davis says.“The and Houston’sartsscene. as well. common threadisthey hadadesire Jarvis Manning Broadway’s “Motown”extends to merge the gapbetween races and Jr.:Whataburger— theater’s recentspate of “juke- cultures.” and CreamBurgerfor box” musicals, showsbuilt Davis is bestknown by her strawberry shakes. on pop catalogs. In this case, stagename,Támar.She sang the unifying factor is not a THEATER the leadvocals with Prince particular singer or group, on his Grammy-nominated but arecord producer.With song “Beautiful, Loved Gordy tells book by BerryGordy, based and Blessed.” Shealso on his autobiography, the show collaborated with Tyler his story in chronicles Gordy’sfounding and Perryonseveral “Madea” operation of the Motown record stageplays. amemoir label, and includescovers of the Shewas in the group manyMotown hits, performed by an Girl’s Tyme with Beyoncé, Berry Gordywanted JARVIS Motowntobea ensemble cast. -

TLJ Winter 2017

TexasLibraryJournal volume 93, number 4 • winter 2017 ALADENVER MIDWINTER Get Inspired! MeetingFEBRUARY & 9–13, Exhibits 2018 Programs BOOK BUZZ THEATER Innovation Discussions Programs Denver Sessions SYMPOSIUM ON THE FUTURE OF LIBRARIES Social Events ALA Publishers Pavilions Organizations SCHEDULER MIDWINTER Experts LIVE STAGES Librarians CONNECTIONS Awards Committees LIBRARIES AUTHORS ALA Store POPTOP STAGE LEARNING Preconferences RUSA AWARDS TICKETED Networking YOUTH MEDIA 2018 Uncommons EVENTS AWARDS Mobile App Peer ALA Master Series Books News Networking PRESIDENT’S PROGRAM News You Can Use EXHIBITS Speakers ELIZABETH JUNOT DÍAZ BILL NYE MARLEY DIAS ACEVEDO Author Author and Author and Activist Author and Poet TV Personality DAVE GREGORY PATRISSE CULLORS EGGERS MONE Activist, Author and Author Author Performance Artist Find dates and other details for specific events in Can’t attend the whole event? the conference scheduler at alamidwinter.org Choose specific days to attend, or exhibits-only. ALAMIDWINTER.ORG TEXAS LIBRARY JOURNAL Conference Edition contents Volume 93, No 4 Winter 2017 Published by the TEXAS LIBRARY President’s Perspective: Advocacy and Storytelling .....Ling Hwey Jeng ...... 2 ASSOCIATION From the Editor ................................................... Wendy Woodland ...... 4 ALADENVER MIDWINTER OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES IN HIGHER EDUCATION Get Inspired! Membership in TLA is open to any Advocate for Open ................................................... Dean Hendrix ...... 6 individual or institution interested -

Evaluating Media Performance 3 Pippa Norris and Sina Odugbemi

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PUBLIC Public Disclosure Authorized SENTINEL NEWS MEDIA & GOVERNANCE REFORM PIPPA NORRIS, Editor Public Disclosure Authorized PUBLIC SENTINEL NEWS MEDIA & GOVERNANCE REFORM PUBLIC SENTINEL NEWS MEDIA & GOVERNANCE REFORM PIPPA NORRIS Editor Copyright © 2010 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 This volume is the product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank of the legal status of any terri- tory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly to reproduce portions of the work. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, Tel: 978-750-8400, Fax: 978-750-4470, www.copyright.com. -

Final Thesis

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Kiana Tipton 2018 The Thesis Committee for Kiana Tipton Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Thesis: Recording the Movement: The Role of Citizen-Generated Videos in Perceptions of Police and Police Use of Deadly Force APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Samuel Craig Watkins, Supervisor Wenhong Chen Recording the Movement: The Role of Citizen-Generated Videos in Perceptions of Police and Police Use of Deadly Force by Kiana Tipton Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Dedication To my dad, who has been a victim of the very system that supposedly set us free- I know you are trying- this research is for you. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor, and friend, Craig Watkins for being a mentor to me over the last two years and going out of his way to make sure I felt like I belonged in the intimidating space of academia. Thank you for believing in and encouraging me. I would also like to thank Professor Chen for her patience and kindness over the past two years, and introducing me to the scary but fulfilling research of social networks and quantitative analysis. To Jennifer McClearen, I am so happy I had the opportunity to take two of your classes in your time at UT. -

Case 4:20-Cv-02120 Document 1 Filed on 06/16/20 in TXSD Page 1 of 7

Case 4:20-cv-02120 Document 1 Filed on 06/16/20 in TXSD Page 1 of 7 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION PEGGY NAN MOORE, Plaintiff, CA NO.___________ v. KIAH, LLC, and NEXSTAR MEDIA GROUP, INC.,1 Jury Demanded Defendants, PLAINTIFF’S ORIGINAL COMPLAINT TO THE HONORABLE JUDGE OF SAID COURT: 1. PRELIMINARY STATEMENT 1.1. Plaintiff demands a JURY TRIAL in this employment discrimination and retaliation case as to any and all issues triable to a jury. Plaintiff alleges Defendants KIAH, LLC and Nexstar Media Group, Inc. discriminated against Plaintiff when Defendants KIAH, LLC and Nexstar Media Group, Inc. took adverse personnel actions against Plaintiff. 1.2 COMES NOW, PEGGY NAN MOORE, (hereinafter referred to as “Plaintiff”) complaining of and against KIAH, LLC (hereinafter referred to as “Defendant KIAH”) and Nexstar Media Group, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as “Defendant Nexstar”), and for cause of action respectfully shows the court the following: 2. PARTIES 2.1. Plaintiff is an individual who resides in Houston, Harris County, Texas. 1 Defendant identified Nexstar Media Group, Inc, as the parent company of Plaintiff’s employer. Nextstar Media Group Inc, purchased Tribune Media and assumed its debt and liability, Tribune Media was Plaintiff’s employer and co employer at the time of termination, and named in her EEOC charge. Page | 1 PLAINTIFF’S ORIGINAL COMPLAINT Case 4:20-cv-02120 Document 1 Filed on 06/16/20 in TXSD Page 2 of 7 2.2. Defendant KIAH, LLC., is an employer in Texas employs more than 20 employees and engages in interstate commerce. -

May 2020 Executive Summary

MAY 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY GALVESTON ISLAND CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU For May we produced 14 leads with 5,538 potential room nights. In addition, we had 4 Definite Bookings resulting in 1,412 room nights with an estimated economic impact of $2,152,364. Year to Date Definite Bookings are 41,434 future room nights. The definite business booked year to date has a potential economic impact of approximately $35,821,044 for Galveston Island. (Note: This figure is based on Destination International’s Economic Impact Calculator.) Definites: 4 2020 – 2 2021 – 1 2022 - 1 ACTIVITIES & UPDATES: TRADE SHOWS/SALES EVENTS: No events due to COVID-19 INDUSTRY MEETINGS/NETWORKING: Numerous webinars and industry research presentations, virtual, All TCVBA Virtual Happy Hour, Dottie Texas City/La Marque Chamber Women in Business virtual meeting, Tiffaney SITE VISITS/ CLIENT APPOINTMENTS/FAMS: Southeast Homicide Investigators Association, 2021, Ciara Bates Travel client dinner, 2021, Tiffaney DESTINATION SERVICES Group Serviced: 19 events serviced / 0 total attendance Group/Partner Meetings and Special Events TTA daily state of the industry and best practices Convention Services After Covid-19 Crisis, Venue Perspective, ESPA, Convention Services After Covid-19 Crisis, CVB Perspective, ESPA Longwoods Webinar TRA Survival Plan Webinar by request of TRA Virtual Town Hall with Senator Ted Cruz, Chamber of Commerce Good Morning Galveston, Featuring Leonard Woolsey and The GDN Attended Women’s Conference Planning Meeting Virtual meetings with partners include: Tod Schott, Jane Park, Schlitterbahn, Jim O’Neil, Saltwater Recon, Yaga’s, Taquilo’s, Bubba Gump, Gaido’s, Katie’s Seafood House, Gracie’s, LaKing’s Confectionary, Tsunami, Stuttgarden Tavern, Rudy & Paco’s, Mosquito Café, Saltwater Grill, O’Malleys, Murphy’s, Clay Cup Studios, Old Cellar, Jammin, Molly’s, Maceo’s, Ohana, SUP, East Beach Cantina, Blvd. -

Facebook.Com Twitter.Com

research.net victoriapride.com skydrive.live.com thedanishparliament.dkft.dk vanpride.bc.ca climateoutreach.org.uk tns-counter.rusoft.rambler.ruimg04.rl0.rumir.travelad.rambler.rueda.rulenta.rufoto.rambler.ruadme.ruhelp.rambler.ruprice.rum.rambler.ruautorambler.ruimg02.rl0.ruimg.rl0.ruag.rutop100.rambler.rupsychologies.ruad.adriver.rukanobu.runova.rambler.ruepic.kanobu.rulove.rambler.ruaudio.rambler.rur0.rufinance.rambler.rulogc278.xiti.commotor.ruhoroscopes.rambler.rutv.rambler.ruh02.rl0.ruimg03.rl0.runightparty.ruid.rambler.rutravel.rambler.rusmartnews.rucosmo.rugazeta.rulooksima.ruavia.rambler.rucounter.rambler.ruferra.ruweather.rambler.rufashiontime.runews.rambler.rureklama.rambler.rurealty.rambler.ruwhrussia.rusobesednik.rumail.rambler.ruimages.rambler.rugames.kanobu.ruimg01.rl0.ru rambler.ru uk.lifestyle.yahoo.comuk.toolbar.yahoo.com uk.images.search.yahoo.comuk.apps.search.yahoo.comuk.shopping.yahoo.net microsoftadvertising.co.uk uk.altavista.com gdatp.com uk.weather.yahoo.com uk.answers.yahoo.comuk.yahoo.com uk.safely.yahoo.com uk.video.search.yahoo.comuk.news.search.yahoo.comuk.docs.yahoo.comuk.search.yahoo.com ar.tns-counter.rukassa.rambler.ru uk.finance.yahoo.com mx.yhs4.search.yahoo.com br.yhs4.search.yahoo.com uk.mobile.yahoo.comuk.omg.yahoo.com ar.yhs4.search.yahoo.com at.yhs4.search.yahoo.com uk.cars.yahoo.com uk.eurosport.yahoo.com advertising.yahoo.co.uk nz.yhs4.search.yahoo.com kp.ru everything.yahoo.com nl.yhs4.search.yahoo.com uk.yhs4.search.yahoo.com uk.finsearch.yahoo.com fi.yhs4.search.yahoo.comse.yhs4.search.yahoo.com -

CTCP December Press Briefing Coverage Report 1-18-2013.Xlsx

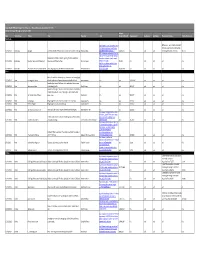

State Health Officer's Report on Tobacco -- Teleconference, December 13, 2012 Media Coverage through January 18, 2013 Unique Date Outlet Type Outlet Title Reporter Link Visitors/Month Impressions Audience Ad Value Posted on Twitter Twitter Followers Syndicate http://www.reuters.com/article/2012 @Reuters_Health: California health /12/14/us-usa-tobacco-california- officials sound alarm over hookah 12/13/2012 Syndicate Reuters California health officials sound alarm over hookah smoking Ronnie Cohen idUSBRE8BD04K20121214 5,070,474 n/a n/a n/a smoking http://bit.ly/Veayzu 34,277 http://sfappeal.com/news/2012/12/d epartment-of-public-health-fighting- Department Of Public Health Fighting To Make California to-make-california-cigarette-and- 12/13/2012 Syndicate Bay City News via SFAppeal.com Cigarette and Tobacco Free Bay City News tobacco-free.php 11,051 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a http://news.yahoo.com/state-big- surge-calif-smokeless- 12/14/2012 Syndicate Associated Press via Yahoo! News State: Big surge in Calif. smokeless tobacco sales Associated Press 025013382.html 60,009,565 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a Print Sales of smokeless tobacco jump; Increased use among high 12/14/2012 Print Los Angeles Times school students is of special concern to health officials. Anna Gorman n/a n/a 1,603,422 n/a n/a n/a n/a Smoking declines in California, but smokeless tobacco use 12/14/2012 Print Sacramento Bee rises among youth David Siders n/a n/a 480,497 n/a n/a n/a n/a Number of Young Smokers In State Rises; Wider availability of tobacco products, new marketing in bars contributed, 12/14/2012 Print San Diego Union‐Tribune expert says Paul Sisson n/a n/a 520,977 n/a n/a n/a n/a 12/14/2012 Print Daily News Illegal cigarette sales to teens on the rise, report says Susan Abrams n/a n/a 219,547 n/a n/a n/a n/a 12/14/2012 Print Press‐Telegram Illegal cigarette sales to minors up Susan Abrams n/a n/a 202,367 n/a n/a n/a n/a 12/14/2012 Print San Francisco Chronicle Virus may offer cancer insight (Weekly Health Report) Stephanie M. -

Is Preventing Breast Cancer Possible?

Sunday,Section October C 15, 2017 The Baytown Sun 1C The Baytown Sun Sunday, October 15, 2017 Dr. Hannah Chung Dr. Esther Dubrovsky Dr. Mary Goswitz Is Preventing Breast Cancer Possible? By Rod Evans, developing a variety of serious diseases, including Taking Preventive Medications “DBT separates the layers of the overlapping Houston Methodist San Jacinto Hospital breast cancer. Women who have more fat cells and Interventions tissue, which improves the ability to find While many breast cancer risk factors can’t be produce more estrogen and tend to have higher early cancers, which directly correlates with controlled—the patient’s age or family history, for insulin levels, both of which are linked to an If you’re at higher risk for breast cancer, cancer survival,” said fellowship trained breast example—new research suggests breast cancer increased breast cancer risk. your doctor may recommend medications radiologist Hannah Chung, MD, director of the may be more preventable than experts originally such as tamoxifen and raloxifene to lower Breast Care Center at Houston Methodist San thought. Limit Alcohol your risk. If you have a strong family history Jacinto Hospital. “Women can take steps to mitigate their risk Limiting alcohol to three or less alcoholic drinks of breast cancer, talk with your doctor about “It’s simply a better mammogram and one I of developing breast cancer and increase their per week can lower a woman’s risk. Goswitz whether genetic testing is right for you. would get myself.” chances of survival if it occurs,” said Dr. Mary recommended that women who don’t want to Mutations in certain genes, such as the BRCA Houston Methodist Cancer Center at San Goswitz, radiation oncologist with the Cancer abstain take a daily multivitamin with folate (folic genes, increase the risk of breast cancer.