Three Commentaries on the Yerushalmi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

1 a Public Torah Reading Without a Minyan?

A Public Torah Reading Without a Minyan? By Rabbi David Silverberg In the Hilkhot Tefila section of his Mishneh Torah (13:6), Maimonides issues a perplexing ruling relevant to the public reading of Parashat Vezot Haberakha, the final portion in the Torah. Namely, Maimonides rules that the final eight verses of the Torah may be formally read in the synagogue without the presence of a minyan. Normally, of course, the public Torah reading (with the accompanying berakhot) requires a minyan, but this requirement is waived when it comes to the final eight verses of the Torah. The basis of Maimonides’ ruling is the Gemara’s discussion in Masekhet Bava Batra (15a), where a debate is recorded as to whether or not Moshe wrote these final eight verses. The Torah in these verses relates the death of Moshe and the ensuing period of mourning observed by Benei Yisrael, giving rise to the question of whether or not Moshe wrote this material before his death. After recording the differing opinions on the matter, the Gemara cites the ambiguous comment of Rav that these verses are read “by a yachid.” The straightforward meaning of this comment, as Maimonides rules, is that with regard to these verses we suspend the general rule requiring the presence of a minyan. Most other authorities, however, offered different readings of this passage, as they found it difficult to explain why these eight verses should be treated differently from the rest of the Torah in this regard. The presence of a minyan is one of the fundamental requirements of the public Torah reading. -

Sim Shalom: the Perfect Prayer

Rabbi Menachem Penner Focusing on Max and Marion Grill Dean, RIETS Tefilla SIM SHALOM: THE PERFECT PRAYER e end the Amidah — makes peace in His heights.” G-d, the Torah of life, love of kindness, both on weekdays and Masekhet Derekh Eretz, Perek righteousness, blessing, mercy, life and holy days — with a Shalom no. 19 peace. tefillahW for peace. This is in keeping There are, however, multiple reasons Moreover, the closing (and opening) with the tradition of concluding our to question whether Sim Shalom is a berakhot of Shemoneh Esreh — prayers with the hope for shalom: mere request for peace. Retzei, Modim, and Sim Shalom — אמר ר' יהושע דסכנין בשם ר' לוי גדול השלום Indeed, the first half of the berakhah are not supposed to be requests at all! - שכל הברכות והתפלות חותמין בשלום: אמר רב יהודה לעולם אל ישאל אדם צרכיו :asks for more than peace קרית שמע - חותמה בשלום - "ופרוס סוכת לא בג' ראשונות ולא בג' אחרונות - אלא ָ לֹוםשִ ים ׁשטֹוָבה ּובְ ָרָכֵה חָן ו ֶֽחֶסד וְ ַרֲחמִ ים באמצעיות: שלומך". ברכת כהנים - חותמה בשלום ָע ֵֽלינּו וְ ַעָל כל יִשְ ָרֵאַל ע ָברְ ֶֽמָך׃ ֵֽכנּוָ, אבִֽ ינּוֻ, כ ָֽלנּו - שנאמר "וישם לך שלום". וכל הברכות - R’ Yehudah said: A person should not כְ ֶאָחד בְ ָאֹור כִי בְ פֶֽניָך ָאֹור נ פֶֽנָיָךַֽתָת ָֽ לנּו ה' חותמין בשלום - "עושה שלום במרומיו." ask for his needs — not during the first ֱאֹלקינּו ת ַֹורַת חיִים וְ ַֽאֲהַב ֶֽת חֶסד ּוצְ ָדָקה ּובְ ָרָכה Said R’ Yehoshua of Sachnin in the of the Amidah] and not] וְ three blessingַרֲחמִ ים וְ ַחיִים וְ ָ ׁשלֹום׃ name of R’ Levi: All the blessings and during the last three blessings. -

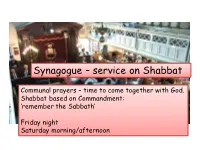

Synagogue – Service on Shabbat

Synagogue – service on Shabbat Communal prayers – time to come together with God. Shabbat based on Commandment: ‘remember the Sabbath’ Friday night Saturday morning/afternoon Shema Prayers – include Shema, Amidah, reading from the Torah, sermon from Rabbi, use SIDDUR Amidah (order of service) ‘Keep Sabbath holy..’ Commandment Siddur Orthodox – Reform – Service in Hebrew Use own language + Hebrew Unaccompanied songs No reference to Messiah/resurrection Men and women apart Use instruments/recorded music Men and women together AMIDAH .. Core prayer of every Jewish service, it means STANDING 18 blessings Prayer is thePraise bridge God between man and God Prayer daily part of life – Shema Praise/thanksgiving/requestsRequests from God Thanksgiving Recited silently + read by rabbi At the end take 3 steps back /forward (Reform don’t do). Symbolise Whole volume in TALMUD aboutwithdrawing prayer: from God’s presence... BERAKHOT 39 categories of not working – include no SHABBAT: Importantcooking = What happens? ONLY PIKUACH NEFESH = save a 1. Celebrates God’s Prepare home – clean/cook life work can be doneBegins 18 mins before creation (Gen OrthodoxIn don't drive, sunset (Fri) the beginning ..)live near synagogue – Mother lights two candles – Reform do drive have 2. Time of spiritual Shekinah car parks renewal – family Blessing over a loaf Best food served, time Kiddush prayer over wine best crockery, food (‘Blessed are you our God..’ pre-prepared. 3. It is one of the Attend synagogue (Sat) Ten Orthodox follow rules literally – electric Havdalah candle lit – ends CommandmentslightsIs this on timers out of date?Shabbat, holy and world are (keep it holy) Non-orthodox it’s not mixed. -

Is There an Authentic Triennial Cycle of Torah Readings? RABBI LIONEL E

Is there an Authentic Triennial Cycle of Torah Readings? RABBI LIONEL E. MOSES This paper is an appendix to the paper "Annual and Triennial Systems For Reading The Torah" by Rabbi Elliot Dorff, and was approved together with it on April 29, 1987 by a vote of seven in favor, four opposed, and two abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Isidoro Aizenberg, Ben Zion Bergman, Elliot N. Dorff, Richard L. Eisenberg, Mayer E. Rabinowitz, Seymour Siegel and Gordon Tucker. Members voting in opposition: Rabbis David H. Lincoln, Lionel E. Moses, Joel Roth and Steven Saltzman. Members abstaining: Rabbis David M. Feldman and George Pollak. Abstract In light of questions addressed to the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards from as early as 1961 and the preliminary answers given to these queries by the committee (Section I), this paper endeavors to review the sources (Section II), both talmudic and post-talmudic (Section Ila) and manuscript lists of sedarim (Section lib) to set the triennial cycle in its historical perspective. Section III of the paper establishes a list of seven halakhic parameters, based on Mishnah and Tosefta,for the reading of the Torah. The parameters are limited to these two authentically Palestinian sources because all data for a triennial cycle is Palestinian in origin and predates even the earliest post-Geonic law codices. It would thus be unfair, to say nothing of impossible, to try to fit a Palestinian triennial reading cycle to halakhic parameters which were both later in origin and developed outside its geographical sphere of influence. Finally in Section IV, six questions are asked regarding the institution of a triennial cycle in our day and in a short postscript, several desiderata are listed in order to put such a cycle into practice today. -

This Week at YICC Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah

October 9th-16th, 2020 • Tishrei 21-28, 5781 This Week At YICC Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah CHAG SAMEACH! Note: All Minyanim listed below will take place in our Shul’s backyard HALAKHIC CORNER - Shemini Azeret HOSHANA RABBA, Friday, October 9 Shacharit ..................................... 5:45/7:30/9:15 am • On Shemini Atzeret, the Halakha requires that one eat Candles ................................................. 5:14- 6:08 pm both dinner and lunch in the Sukkah. One, however, does Mincha ........................................................... 6:15pm not recite the blessing of “Leshev B’Sukkah” on Shemini Atzeret. SHEMINI ATZERET, Shabbat, October 10 • One recites the blessing of “Shehecheyanu” at Kiddush on Shacharit ................................................... 6:45/8:45 am Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah nights because they Yizkor & Tefilat Geshem are considered separate festivals, unlike the last days of Mincha ................................................................ 6:05 pm Pesach, which are the conclusion of the same holiday. Shiur by Jeff Astrof Maariv ................................................................ 7:10 pm Candles ................................................ after 7:10 pm SIMCHAT TORAH, Sunday, October 11 Shacharit & Hakafot ............................. 7:00/8:45 am TIME TO PLEASE RETURN Mincha .......................................................... 6:10 pm YICC’S HIGH HOLIDAY MAHZORIM Shiur by: Rabbi James Proops Maariv .......................................................... -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Halakhot of Pesah

Founded in 1740 CONGREGATION MIKVEH ISRAEL The Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in the City of Philadelphia HALAKHOT OF PESAH Laws and Customs of Passover THE MONTH OF NISAN Although in counting years we begin with Rosh Hashanah, the first of Tishri, the Torah counts months from Nisan to highlight the great events of Pesah. Parts of Nisan’s days are festive occasions (the first twelve days commemorating the Mishkan’s, Tabernacle’s, dedication followed by Pesah), Tahanunim (supplications) are omitted from prayers the entire month. The Psalms in the latter sections of Shahrit that allude to a ‘day of distress’ (Ya’anukha and Tefila LeDavid) are also omitted when Tahanunim are not recited. When one sees two blossoming fruit trees during Nisan, Bircat Hallanot (blessing of the trees) is recited. This Berakha is recited only once each year. Women also recite it. It may be recited on Shabbat or Yom Tob. Nisan is the proper time for this Berakha, but it may be recited afterwards. It is not recited after the blossoming stage, when the fruits are growing. Eulogies are not permitted during Nisan. When necessary, a short appreciation of the departed, with moral instruction is permitted. The declaration of Siduk Hadin during the Shiva mourning period is omitted. SEARCHING FOR HAMETS As the Torah prohibits possession of Hamets on Pesah, it is mandatory to check one’s home and remove all Hamets before Pesah. Notwithstanding the fact that the home was thoroughly cleansed of Hamets beforehand, on the night before Pesah we perform the Bedikat Hamets, (the search for Hamets), in all places where it might be found. -

Torah from JTS Lecturer in Liturgy and Worship, JTS “Fill Our Eyes with Light

Exploring Prayer :(עבודת הלב) Service of the Heart This week’s column was written by Rabbi Samuel Barth, Senior Torah from JTS Lecturer in Liturgy and Worship, JTS “Fill Our Eyes With Light . Cause Our Hearts to Cling” (Part 1) Phrases in the siddur are filled with echoes of earlier texts and give birth to newer metaphors and meanings. The blessing immediately before the Shema’ in every morning service contains the phrase “ha’er eyneinu beToratekha Parashat Mishpatim vedabek libeinu bemitzvotekha” (Fill our eyes with the light of Your Torah, and Shabbat Shekalim make our hearts cleave to Your mitzvot.) [Siddur Sim Shalom, 32.] Light is a recurring metaphor in our sources; we recall Proverbs 6:23: “The Exodus 21:1–24:18 mitzvah is a lamp and Torah is light,” and an even more compelling image in February 9, 2013 Proverbs 20:27 that “the human soul is the candle of God.” The previous blessing ends with a plea for a new (and perhaps supernal) light to shine upon 29 Shevat 5773 Zion, and this paragraph picks up the metaphor, asking that our eyes be filled with the light of the Torah. Some translations use the phrase “enlighten our eyes,” which has an echo of the quite different eastern religious concept of Parashah Commentary “samsara/nirvana” (often rendered with the English word enlightenment). It seems to me that this proverb is not asking for this profound, ultimate This week’s commentary was written by Rabbi Lisa Gelber, Associate enlightenment, but that we see the world through the insights and wisdom of Dean, The Rabbinical School, JTS. -

Prayer Service of the Heart

Prayer: Service of the Heart Rabbi Dr Bradley Shavit Artson נוּ ְשׁ ַלּ ְמ ָה ִיָפםר ֵוּנָיְשׂתפ We shall offer the words of our lips instead of calves. Hosea 14:3 ברע רבוק םיצורה שא י הח האומה יושעמ ילוק . In the evening, morning, & afternoon I will speak and cry aloud & God will hear my voice. Psalms 55:18 A person should first praise the Holy Blessing One and then pray. Berakhot 32b Cast your eyes downward as though looking at the ground and your heart upward as though standing in heaven. Yevamot 105b A person who washes his hands, puts on Tefillin, says the Sh’ma and prays is considered to have built an altar and offered sacrifice. Such a one is also said to have truly accepted the yoke of heaven. Berakhot 14b-15a יא - וז יהא בע ו הד בש ל ב ? וז פת הל . Which is the service of the heart? This is prayer. Ta’anit 2a בר י עלא ז ר ביהי רפ ו הט נעל י רהוד לצמ י , רמא , כדת י ב : נא י קדצב חא ז ה נפ ךי . Rabbi Elazar used to give a perutah to a pauper and then pray. He said, It is written: I shall behold Your face through tzedakah. Bava Batra 10a Said the Holy One to Israel, I have told you that when you pray, you should pray in the synagogue of your city. If you cannot pray in the synagogue, pray in your field. If you cannot pray in your field, pray in your house.