Birkat Hamazon Berakhot 20B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Bakeries Which Are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? a Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER

Should Bakeries Which are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? A Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER This paper was submitted as a response to the responsum written by Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz and Ms. Dvora Weisberg entitled "Rabbinic Supervision of Jewish Owned Businesses Operating on Shabbat" which was adopted by the CJLS on February 26, 1986. Should rabbis offer rabbinic supervision to bakeries which are open on Shabbat? i1 ~, '(l) l'\ (1) The food itself is indeed kosher after Shabbat, once the time required to prepare it has elapsed. 1 The halakhah is according to Rabbi Yehudah and not according to the Mishnah which is Rabbi Meir's opinion. (2) While a Jew who does not observe all the mitzvot is in some instances deemed trustworthy, this is never the case regarding someone who flagrantly disregards the laws of Shabbat, especially for personal profit. Maimonides specifically excludes such a person's trustworthiness regarding his own actions.2 Moreover in the case of n:nv 77n~ (a violator of Shabbat) Maimonides explicitly rejects his trustworthiness. 3 No support can be brought from Moshe Feinstein who concludes, "even if the proprietor closes his store on Shabbat, [since it is known to all that he does not observe Shabbat], we assume he only wants to impress other observant Jews so they will buy from him."4 Previously in the same responsum R. Feinstein emphasizes that even if the person in The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. -

Women As Shelihot Tzibur for Hallel on Rosh Hodesh

MilinHavivinEng1 7/5/05 11:48 AM Page 84 William Friedman is a first-year student at YCT Rabbinical School. WOMEN AS SHELIHOT TZIBBUR FOR HALLEL ON ROSH HODESH* William Friedman I. INTRODUCTION Contemporary sifrei halakhah which address the issue of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh are unanimous—they are entirely exempt (peturot).1 The basis given by most2 of them is that hallel is a positive time-bound com- mandment (mitzvat aseh shehazman gramah), based on Sukkah 3:10 and Tosafot.3 That Mishnah states: “One for whom a slave, a woman, or a child read it (hallel)—he must answer after them what they said, and a curse will come to him.”4 Tosafot comment: “The inference (mashma) here is that a woman is exempt from the hallel of Sukkot, and likewise that of Shavuot, and the reason is that it is a positive time-bound commandment.” Rosh Hodesh, however, is not mentioned in the list of exemptions. * The scope of this article is limited to the technical halakhic issues involved in the spe- cific area of women’s obligation to recite hallel on Rosh Hodesh as it compares to that of men. Issues such as changing minhag, kol isha, areivut, and the proper role of women in Jewish life are beyond that scope. 1 R. Imanu’el ben Hayim Bashari, Bat Melekh (Bnei Brak, 1999), 28:1 (82); Eliyakim Getsel Ellinson, haIsha vehaMitzvot Sefer Rishon—Bein haIsha leYotzrah (Jerusalem, 1977), 113, 10:2 (116-117); R. David ben Avraham Dov Auerbakh, Halikhot Beitah (Jerusalem, 1982), 8:6-7 (58-59); R. -

Download Ji Calendar Educator Guide

xxx Contents The Jewish Day ............................................................................................................................... 6 A. What is a day? ..................................................................................................................... 6 B. Jewish Days As ‘Natural’ Days ........................................................................................... 7 C. When does a Jewish day start and end? ........................................................................... 8 D. The values we can learn from the Jewish day ................................................................... 9 Appendix: Additional Information About the Jewish Day ..................................................... 10 The Jewish Week .......................................................................................................................... 13 A. An Accompaniment to Shabbat ....................................................................................... 13 B. The Days of the Week are all Connected to Shabbat ...................................................... 14 C. The Days of the Week are all Connected to the First Week of Creation ........................ 17 D. The Structure of the Jewish Week .................................................................................... 18 E. Deeper Lessons About the Jewish Week ......................................................................... 18 F. Did You Know? ................................................................................................................. -

The Intersection of Gender and Mitzvot Dr

The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies Walking with Mitzvot Edited By Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson ogb hfrs andvhfrs Rabbi Patricia Fenton In Memory of Harold Held and Louise Held, of blessed memory The Held Foundation Melissa and Michael Bordy Joseph and Lacine Held Robert and Lisa Held Published in partnership with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the Rabbinical Assembly, the Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs and the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism. THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER AND MITZVOT DR. RABBI ARYEH COHEN TO START WITH A COUPLE alakhah, or Jewish Law, it has been often noted, is as much a pedagogical system as a legal system. The goal of the Hmitzvot as codified and explicated in the halakhic system is to create a certain type of person. Ideally this is a person who is righteous and God fearing, a person who feels and fulfills their obligation towards God as well as towards their fellows. Embedded into this goal, of necessity, is an idea or conception of what a person is. On the most basic level, the mitzvot “construct” people as masculine and feminine. This means that the halakhic system, or the system of mitzvot as practiced, classically define certain behaviors as masculine and others as feminine. The mitzvot themselves are then grouped into broad categories which are mapped onto male and female. Let’s start with a couple of examples. The (3rd century CE) tractate Kiddushin of the Mishnah begins with the following law: “A woman is acquired in three ways, with money, with a contract and with sex.” The assumption here is that a man “acquires” a woman in marriage and not the reverse. -

Yamim Noraim Flyer 12-Pg 5771

Days of Awe ………….. 5771 Rabbi Linda Holtzman • Rabbi Yael Levy Dina Schlossberg, President • Rabbit Brian Walt, Rabbi Emeritus Gabrielle Kaplan Mayer, Coordinator of Spiritual Life for Children & Youth Rivka Jarosh, Education Director 4101 Freeland Avenue • Philadelphia, PA 19128 Phone: 215-508-0226 • Fax: 215-508-0932 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.mishkan.org DAYS OF AWE 5771 Shalom, Welcome to a year of opportunity at Mishkan Shalom! Our first of many opportunities will be that of starting the year together at services for the Yamim Noraim. It is a pleasure to begin the year as a community, joining old friends and new, praying and learning together. This year, Rabbi Yael Levy will not be with us at the services for the Yamim Noraim. We will miss Rabbi Yael, and hope that her sabbatical time is fulfilling and energizing and that we will learn much from her when she returns to Mishkan Shalom in November. Our services will feel different this year, but the depth and talent of our many members who will participate will add real beauty to them. I am thrilled that joining us to lead the davening will be Sue Hoffman, Rabbi Rebecca Alpert, Cindy Shapiro, Karen Escovitz (Otter), Elliott batTzedek, Wendy Galson, Susan Windle, Andy Stone, Bill Grey, Dan Wolk, several of our teens and many other Mishkan members. As we look ahead to the new year, we pray that 5771 will be filled with abundant blessings for us and for the world. I look forward to celebrating with you. L’shalom, Rabbi Linda Holtzman SECTION 1: LOCATION , VOLUNTEER FORM , FEES AND SERVICE INFORMATION A: WE HAVE • Morning services on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and all services on Yom Kippur will be held at the Haverford School . -

Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon

301 Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon By: ZVI RON In this article we investigate the origin and development of saying vari- ous Psalms and selected verses from Psalms before Birkat Ha-Mazon. In particular, we will attempt to explain the practice of some Ashkenazic Jews to add Psalms 145:21, 115:18, 118:1 and 106:2 after Ps. 126 (Shir Ha-Ma‘alot) and before Birkat Ha-Mazon. Psalms 137 and 126 Before Birkat Ha-Mazon The earliest source for reciting Ps. 137 (Al Naharot Bavel) before Birkat Ha-Mazon is found in the list of practices of the Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe Cordovero (1522–1570). There are different versions of this list, but all versions include the practice of saying Al Naharot Bavel.1 Some versions specifically note that this is to recall the destruction of the Temple,2 some versions state that the Psalm is supposed to be said at the meal, though not specifically right before Birkat Ha-Mazon,3 and some versions state that the Psalm is only said on weekdays, though no alternative Psalm is offered for Shabbat and holidays.4 Although the ex- act provenance of this list is not clear, the parts of it referring to the recitation of Ps. 137 were already popularized by 1577.5 The mystical work Seder Ha-Yom by the 16th century Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe ben Machir was first published in 1599. He also mentions say- ing Al Naharot Bavel at a meal in order to recall the destruction of the 1 Moshe Hallamish, Kabbalah in Liturgy, Halakhah and Customs (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2000), pp. -

Rosh Hashanah Jewish New Year

ROSH HASHANAH JEWISH NEW YEAR “The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelite people thus: In the seventh month, on the first day of the month, you shall observe complete rest, a sacred occasion commemorated with loud blasts. You shall not work at your occupations; and you shall bring an offering by fire to the LORD.” (Lev. 23:23-25) ROSH HASHANAH, the first day of the seventh month (the month of Tishri), is celebrated as “New Year’s Day”. On that day the Jewish people wish one another Shanah Tovah, Happy New Year. ש נ ָׁהָׁטוֹב ָׁה Rosh HaShanah, however, is more than a celebration of a new calendar year; it is a new year for Sabbatical years, a new year for Jubilee years, and a new year for tithing vegetables. Rosh HaShanah is the BIRTHDAY OF THE WORLD, the anniversary of creation—a fourfold event… DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING NEW YEAR’S DAY One of the special features of the Rosh HaShanah prayer [ רֹאשָׁהַש נה] Rosh HaShanah THE DAY OF SHOFAR BLOWING services is the sounding of the shofar (the ram’s horn). The shofar, first heard at Sinai is [זִכְּ רוֹןָׁתְּ רּועה|יוֹםָׁתְּ רּועה] Zikaron Teruah|Yom Teruah THE DAY OF JUDGMENT heard again as a sign of the .coming redemption [יוֹםָׁהַדִ ין] Yom HaDin THE DAY OF REMEMBRANCE THE DAY OF JUDGMENT It is believed that on Rosh [יוֹםָׁהַזִכְּ רוֹן] Yom HaZikaron HaShanah that the destiny of 1 all humankind is recorded in ‘the Book of Life’… “…On Rosh HaShanah it is written, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed, how many will leave this world and how many will be born into it, who will live and who will die.. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

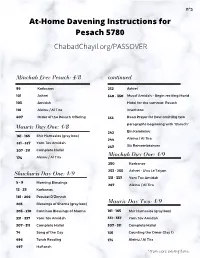

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

The Marriage Issue

Association for Jewish Studies SPRING 2013 Center for Jewish History The Marriage Issue 15 West 16th Street The Latest: New York, NY 10011 William Kentridge: An Implicated Subject Cynthia Ozick’s Fiction Smolders, but not with Romance The Questionnaire: If you were to organize a graduate seminar around a single text, what would it be? Perspectives THE MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Marriage Issue Jewish Marriage 6 Bluma Goldstein Between the Living and the Dead: Making Levirate Marriage Work 10 Dvora Weisberg Married Men 14 Judith Baskin ‘According to the Law of Moses and Israel’: Marriage from Social Institution to Legal Fact 16 Michael Satlow Reading Jewish Philosophy: What’s Marriage Got to Do with It? 18 Susan Shapiro One Jewish Woman, Two Husbands, Three Laws: The Making of Civil Marriage and Divorce in a Revolutionary Age 24 Lois Dubin Jewish Courtship and Marriage in 1920s Vienna 26 Marsha Rozenblit Marriage Equality: An American Jewish View 32 Joyce Antler The Playwright, the Starlight, and the Rabbi: A Love Triangle 35 Lila Corwin Berman The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: How the Gender of the Jewish Parent Influences Intermarriage 42 Keren McGinity Critiquing and Rethinking Kiddushin 44 Rachel Adler Kiddushin, Marriage, and Egalitarian Relationships: Making New Legal Meanings 46 Gail Labovitz Beyond the Sanctification of Subordination: Reclaiming Tradition and Equality in Jewish Marriage 50 Melanie Landau The Multifarious -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

Shavuot Nation 5774

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG ISRAEL Shavuot Nation 5774 JEWISH EDITION Compiled by Gabi Weinberg Teen Program Director ! Table of Contents Sources: Got Milk? Or, Perhaps we should be eating meat on Shavuot? page 4 Shiur Guide: Got Milk? Or, Perhaps we should be eating meat on Shavuot? page 7 Sources: Just Dress? Or is Tzniut something more? page 10 Shiur Guide: Just Dress? Or is Tzniut something more? page 12 Sources: Do Jews have horns? If!Moshe!didn't!have!horns,!what!did!he!have?!page!20 Sources: Do Jews have horns? If!Moshe!didn't!have!horns,!what!did!he!have?!page!24 Shiur Guide: Pronouncing the “Z” in Pizza – which bracha is right? page 28 Shiur Guide: Pronouncing the “Z” in Pizza, which bracha is right? page 32 12:00AM - 1:00AM Welcome and Opening Shiur: Got Milk? Or Perhaps we should be eating meat on Shavuot? • 1:00 - 1:10 Snack Break 1:15AM - 2:00AM Just Dress? Or is Tzniut something more? • 2:00 - 2:45 - Big Food, BBQ, Sushi or Alternative fun food 2:50AM - 3:35AM Sources:!Do!Jews!have!horns?!If!Moshe!didn't!have!horns,! what!did!he!have? • 3:35!B!3:45!Final!Snack!Break! 3:40AM!B!4:25AM!Pronouncing!the!“Z”!in!Pizza,!which!bracha!is!right?! • Wash!hands!and!Say!Brachot!Before!TePillah! 4:30!B!Shacharit!! Dear Young Israel Community, Shavuot is a special time of year where we put an extra emphasis on limmud Torah, study of Torah. The concept of a tikkun leil Shavuot, staying up all night immersed in Torah study, started as a kabbalistic custom that became popular across all sections of Judaism in the late 16th-century.