The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, the Separation of Powers, and Treaty Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 104–582 "!

104TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 104±582 "! PROVIDING FOR THE CONSIDERATION OF H.R. 3144, THE DEFEND AMERICA ACT OF 1996 MAY 16, 1996.ÐReferred to the House Calendar and ordered to be printed Mr. DIAZ-BALART, from the Committee on Rules, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H. Res. 438] The Committee on Rules, having had under consideration House Resolution 438, by a nonrecord vote, report the same to the House with the recommendation that the resolution be adopted. BRIEF SUMMARY OF PROVISIONS OF RESOLUTION The rule provides for consideration in the House with two hours of debate divided equally between the chairman and ranking mi- nority member of the Committee on National Security. The rule waives all points or order against the bill and against its consider- ation. The rule also makes in order without intervention of any point of order one minority amendment in the nature of a substitute to be offered by Mr. Spratt or his designee and which is printed in this report. The rule provides that the substitute shall be debatable separately for one hour divided equally between the proponent and an opponent. Finally, the rule provides for one motion to recommit with or without instructions. THE AMENDMENT TO BE OFFERED BY REPRESENTATIVE SPRATT OF SOUTH CAROLINA, OR A DESIGNEE, DEBATABLE FOR 1 HOUR Strike all after the enacting clause and insert the following: SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ``Ballistic Missile Defense Act of 1996''. SEC. 2. FINDINGS. Congress makes the following findings: 29±008 2 (1) Short-range theater ballistic missiles threaten United States Armed Forces wherever engaged abroad. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

Kazakhstan Missile Chronology

Kazakhstan Missile Chronology Last update: May 2010 As of May 2010, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the Kazakhstan Missile Overview. This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2009-1947 March 2009 On 4 March 2009, Kazakhstan signed a contract to purchase S-300 air defense missile systems from Russia. According to Ministry of Defense officials, Kazakhstan plans to purchase 10 batteries of S-300PS by 2011. Kazakhstan's Air Defense Commander Aleksandr Sorokin mentioned, however, that the 10 batteries would still not be enough to shield all the most vital" facilities designated earlier by a presidential decree. The export version of S- 300PS (NATO designation SA-10C Grumble) has a maximum range of 75 km and can hit targets moving at up to 1200 m/s at a minimum altitude of 25 meters. -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Air-Directed Surface-To-Air Missile Study Methodology

H. T. KAUDERER Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile Study Methodology H. Todd Kauderer During June 1995 through September 1998, APL conducted a series of Warfare Analysis Laboratory Exercises (WALEXs) in support of the Naval Air Systems Command. The goal of these exercises was to examine a concept then known as the Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System in support of Navy Overland Cruise Missile Defense. A team of analysts and engineers from APL and elsewhere was assembled to develop a high-fidelity, physics-based engineering modeling process suitable for understanding and assessing the performance of both individual systems and a “system of systems.” Results of the initial ADSAM Study effort served as the basis for a series of WALEXs involving senior Flag and General Officers and were subsequently presented to the (then) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology. (Keywords: ADSAM, Cruise missiles, Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense, Modeling and simulation, Overland Cruise Missile Defense.) INTRODUCTION In June 1995 the Naval Air Systems Command • Developing an analytical methodology that tied to- (NAVAIR) asked APL to examine the Air-Directed gether a series of previously distinct, “stovepiped” Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System concept for high-fidelity engineering models into an integrated their Overland Cruise Missile Defense (OCMD) doc- system that allowed the detailed analysis of a “system trine. NAVAIR was concerned that a number of impor- of systems” tant air defense–related decisions were being made -

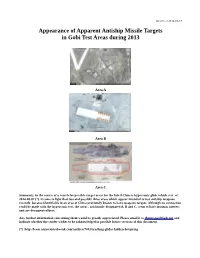

Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas During 2013

Version of 2014-09-15 Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas during 2013 Area A Area B Area C Summary: In the course of a search for possible target areas for the failed Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle test of 2014-08-07 (*), it came to light that two and possibly three areas which appear intended to test antiship weapons recently became identifiable in an area of China previously known to have weapons targets. Although no connection could be made with the hypersonic test, the areas , arbitrarily designated A, B and C, seem to have intrinsic interest and are documented here. Any further information concerning them would be greatly appreciated. Please email it to [email protected] and indicate whether the sender wishes to be acknowledged in possible future versions of this document. (*) http://lewis.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/7443/crashing-glider-hidden-hotspring Area A 40.466 N, 93.521 E Area A, 2013-11-04 The three shapes at lower left seem clearly meant to represent ships. The dark chevron around them may represent piers. The objects above them and to the right are unidentified, but might represent shore facilities. Warships in Su-ao Harbor, Taiwan The picture scale is almost the same as in the above image of Area A. Both the pair of actual ships at center and the presumed ship targets are about 170 meters long, closely matching the dimensions of Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Kee Lung-class (ex-Kidd) destroyers. Area A, 2013-08-01 Construction of the ship targets is almost complete. -

NSIAD-90-146 Missile Procurement Executive Summary

I “1 .” II ..._ -111”1”~1~ . .. - _-.. .- _ _.._.l:rril.tvl-_._._ ._ _.._ _. Slillt3_” _.I .,..- I..-- i;tkrrtkral“1”_.1_.-..-- _..------ Ac~orlnt -.-.----.-..---._._- ing Ol’l’iw.._._..- .-...... I “. ~_I ..-.---------- ---_._--.lll__ .-..” ..” *“I,L,“^I.“m”-““-. .11it\ l’tO0. MISSILE PROCUREMENT Further Production of RAAM Should Not Be Approved Until Questions Are Resolved National Security and International Affairs Division H-22 1734 May 4,199O The Honorable Denny Smith I louse of Representatives Dear Mr. Smith: This report addresses the status of the Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) at the scheduled full-rate production milestone. As requested, we focused on the missile’s demonstrated operational performance, the contractors’ readiness to produce quality missiles at the required rates, and the latest program cost estimates. The report concludes that significant questions about AMRAAM'S performance, reliability, producibility, and affordability remain unresolved. It recommends that the Secretary of Defense not approve any additional AMRAAM production until (1) tests demonstrate that the missile can meet all of its critical performance requirements and that its reliability meets the established requirements, (2) both contractors demonstrate that they can consistently produce quality missiles at the rates required by their contracts, (3) the Air Force and the Navy complete their review of missile quantity requirements, and (4) the Department of Defense determines that the AMRAAM program is affordable within realistic future budget projections and consults with the Congress to ensure that the program complies with the adjusted statutory cost cap. The report also suggests that the Congress deny the $1.34 billion requested for AMRAAM procurement in fiscal year 1991. -

Missilesmissilesdr Carlo Kopp in the Asia-Pacific

MISSILESMISSILESDr Carlo Kopp in the Asia-Pacific oday, offensive missiles are the primary armament of fighter aircraft, with missile types spanning a wide range of specialised niches in range, speed, guidance technique and intended target. With the Pacific Rim and Indian Ocean regions today the fastest growing area globally in buys of evolved third generation combat aircraft, it is inevitable that this will be reflected in the largest and most diverse inventory of weapons in service. At present the established inventories of weapons are in transition, with a wide variety of Tlegacy types in service, largely acquired during the latter Cold War era, and new technology 4th generation missiles are being widely acquired to supplement or replace existing weapons. The two largest players remain the United States and Russia, although indigenous Israeli, French, German, British and Chinese weapons are well established in specific niches. Air to air missiles, while demanding technologically, are nevertheless affordable to develop and fund from a single national defence budget, and they result in greater diversity than seen previously in larger weapons, or combat aircraft designs. Air-to-air missile types are recognised in three distinct categories: highly agile Within Visual Range (WVR) missiles; less agile but longer ranging Beyond Visual Range (BVR) missiles; and very long range BVR missiles. While the divisions between the latter two categories are less distinct compared against WVR missiles, the longer ranging weapons are often quite unique and usually much larger, to accommodate the required propellant mass. In technological terms, several important developments have been observed over the last decade. -

The Agenda for Arms Control Negotiations After the Moscow Treaty

The Agenda for Arms Control Negotiations After the Moscow Treaty PONARS Policy Memo 278 Nikolai Sokov Monterey Institute of International Studies October 2002 Ratification of the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT, or the Moscow Treaty), signed by Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush on May 24, 2002, is all but certain. Critics in both capitals have apparently been proven wrong—it turned out to be possible to break with three decades of arms control experience and traditions and to sign a treaty that almost completely lacks substantive provisions; even those that are included into the treaty cannot be efficiently verified. In contrast, this treaty exemplifies the Bush administration’s assertion that the United States and Russia no longer need complicated treaties that impose many restrictions on the maintenance, operation, and modernization of the two countries’ nuclear arsenals. Optimism about near unlimited flexibility, which the new treaty grants both sides, seems misguided, however. Although traditional concerns about a “bolt out of the blue” first strike have no place in the existing environment, both sides still need the reassurance and mutual trust that only a robust transparency regime could provide. Both sides have already proclaimed their intention to pursue further negotiations: the United States appears to favor the exchange of data whereas Russia seems more interested in measures that would limit the uploading capability of the United States. Either way, at issue is the predictability of the U.S.-Russia strategic relationship. The stable cooperative relations between the United States and Russia offer an opportunity that should not be missed. The two sides feel reasonably safe vis-à-vis one another and can afford approaching transparency negotiations without undue haste. -

The Breach: Ukraine's Territorial Integrity and the Budapest Memorandum

Issue Brief #3 Nuclear Proliferation International History Project The Breach: Ukraine’s Territorial Integrity and the Budapest Memorandum Mariana Budjeryn Russia’s annexation of Crimea and covert invasion of eastern Ukraine places an uncomfortable focus on the worth of the security assurances pledged to Ukraine by the nuclear powers in exchange for its denuclearization. In 1994, the three depository states of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)—Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom—extended positive and negative security assurances to Ukraine. The depository states underlined their commitment to Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity by signing the so-called “Budapest Memorandum.”1 Using new archival records, this examination of Ukraine’s search for security guarantees in the early 1990s reveals that, ironically, the threat of border revisionism by Russia was the single gravest concern of Ukraine’s leadership when surrendering the nuclear arsenal. The failure of the Budapest Memorandum to deter one of Ukraine’s security guarantors from military aggression has important implications both for Ukraine’s long-term security and for the value of security assurances for future international nonproliferation and disarmament efforts. Russia’s breach of the Memorandum invites strong scrutiny of other security commitments and opens an enormous rhetorical opportunity for proliferators to lobby for a nuclear deterrent. UKRAINE’S NUCLEAR PREDICAMENT In 1991, Ukraine inherited the world’s third largest more cautious approach to its nuclear inheritance, nuclear arsenal as a result of the collapse of the concerned that Russia’s monopoly on nuclear arms Soviet Union.2 By mid-1996, all nuclear munitions in the post-Soviet space would be conducive to its had been transferred from Ukraine to Russia resurgence as a dominating force in the region. -

Detente Or Razryadka? the Kissinger-Dobrynin Telephone Transcripts and Relaxing American-Soviet Tensions, 1969-1977

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship 2013 Detente or Razryadka? The Kissinger-Dobrynin Telephone Transcripts and Relaxing American- Soviet Tensions, 1969-1977. Daniel S. Stackhouse Jr. Claremont Graduate University Recommended Citation Stackhouse, Daniel S. Jr.. (2013). Detente or Razryadka? The Kissinger-Dobrynin Telephone Transcripts and Relaxing American-Soviet Tensions, 1969-1977.. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 86. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/86. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/86 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Détente or Razryadka? The Kissinger-Dobrynin Telephone Transcripts and Relaxing American-Soviet Tensions, 1969-1977 by Daniel S. Stackhouse, Jr. A final project submitted to the Faculty of Claremont Graduate University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. Claremont Graduate University 2013 Copyright Daniel S. Stackhouse, Jr., 2013 All rights reserved. APPROVAL OF THE REVIEW COMMITTEE This dissertation has been duly read, reviewed, and critiqued by the Committee listed below, which hereby approves the manuscript of Daniel S. Stackhouse, Jr. as fulfilling the scope and quality requirements for meriting the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Janet Farrell Brodie, Chair Claremont Graduate University Professor of History William Jones Claremont Graduate University Professor of History Joshua Goode Claremont Graduate University Professor of History ABSTRACT Détente or Razryadka? The Kissinger-Dobrynin Telephone Transcripts and Relaxing American-Soviet Tensions, 1969-1977 by Daniel S.