The Location of Holographic Wills Kevin Bennardo University of North Carolina School of Law, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Wills Alexandra Gadzo (Palo Alto, California)

CHAPTER 10 Types of Wills ALEXANDRA GADZO (Palo Alto, Calforna) will is used to designate how, when, and to whom your assets will pass at your death. In addition to Anaming an Executor or Executrix (sometimes called a Personal Representative) to collect and distribute your assets, your will is the document in which you name guardians for your minor children. If you have a living trust, a pour over will is generally used so that at your death, the will “pours” any assets not in your living trust into the trust so the assets can be distributed according to the trust’s terms. There may or may not need to be a probate first depending on the amount of the assets. REQUIREMENTS OF A WILL You can draft a typewritten will or have an attorney draft a will for you. In California, the requirements for a will to be legally effective are as follows: • the testator must be 18 years or older; • the testator must be of sound mind; • the document must state that it is a will; • it must be type-written or created and printed using a computer; • you need to appoint at least one executor; • the will must provide for the disposition of your assets; • the will must be signed and have a date of execution; and • two witnesses who are at least 18 years of age must be present when the testator signs the will. These witnesses must also be of sound mind and understand they are witnesses for your will. The witnesses may not be beneficiaries of the will, and the witnesses must see the testator and the other witness sign your will. -

Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Louisiana Law Review Volume 80 Number 4 Summer 2020 Article 9 11-11-2020 Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Ronald J. Scalise Jr., Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, 80 La. L. Rev. (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol80/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................ 1332 I. A (Very Brief) History of Wills in the United States ................. 1333 A. Functions of Form Requirements ........................................ 1335 B. The Law of Yesterday: The Development of Louisiana’s Will Forms ....................................................... 1337 II. Compliance with Formalities ..................................................... 1343 A. The Slow Migration from “Strict Compliance” to “Substantial Compliance” to “Harmless Error” in the United States .............................................................. 1344 B. Compliance in Other Jurisdictions, Civil and Common .............................................................. -

Wills and Trusts (4Thed

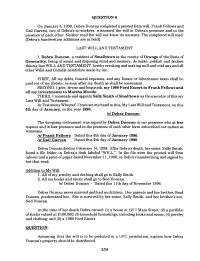

QUESTION 6 On January 5, 1990, Debra Duncan completed a printed form will. Frank Fellows and Gail Garven, two of Debra's co-workers, witnessed the will in Debra's presence and in the presence of each other. Neither read the will nor knew its contents. The completed will read: [Debra's handwritten additions are in bold] LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT I, Debra Duncan, a resident of Smalltown in the county of Orange of the State of Generality, being of sound and dsposing mind and memory, do make, publish and declare this my last WILL AND TESTAMENT, hereby revoking and making null and void any and all other Wills and Codicils heretofore made by me. FIRST, All my debts, funeral expenses, and any Estate or Inheritance taxes shall be paid out of my Estate, as soon after my death as shall be convenient. SECOND, I give, devise and bequeath, my 1989 Ford Escort to Frank Fellows and all my investments to Martha Murdo. THIRD, I nominate and appoint Sally Smith of Smalltown as the executor of this my Last Wlll and Testament. In Testimony Whereof, I have set my hand to this, My Last Will andTestarnent, on this 5th day of January, in the year 1990. IS/ Debra Duncan The foregoing instrument was signed by Debra Duncan in our presence who at her request and in her presence and in the presence of each other have subscribed our names as witnesses. Is/ Frank Fellows Dated this 5th day of January 1990. Is1 Gail Garven Dated this 5th day of January 1990. -

STEVE R. AKERS Bessemer Trust Company, NA 300

THE ANATOMY OF A WILL: PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN WILL DRAFTING* Authors: STEVE R. AKERS Bessemer Trust Company, N.A. 300 Crescent Court, Suite 800 Dallas, Texas 75201 BERNARD E. JONES Attorney at Law 3555 Timmons Lane, Suite 1020 Houston, Texas 77027 R. J. WATTS, II Law Office of R. J. Watts, II 9400 N. Central Expressway, Ste. 306 Dallas, Texas 75231-5039 State Bar of Texas ESTATE PLANNING AND PROBATE 101 COURSE June 25, 2012 San Antonio CHAPTER 2.1 * Copyright © 1993 - 2011 * by Steve R. Akers Anatomy of A Will Chapter 2.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1. NUTSHELL OF SUBSTANTIVE LAW REGARDING VALIDITY OF A WILL................................................................. 1 I. FUNDAMENTAL REQUIREMENTS OF A WILL. 1 A. What Is a "Will"?. 1 1. Generally. 1 2. Origin of the Term "Last Will and Testament".. 1 3. Summary of Basic Requirements. 1 B. Testamentary Intent. 1 1. Generally. 1 2. Instrument Clearly Labeled as a Will.. 2 3. Models or Instruction Letters. 2 4. Extraneous Evidence of Testamentary Intent.. 2 C. Testamentary Capacity - Who Can Make a Will. 2 1. Statutory Provision. 2 2. Judicial Development of the "Sound Mind" Requirement.. 2 a. Five Part Test--Current Rule.. 2 b. Old Four Part Test--No Longer the Law.. 2 c. Lucid Intervals. 3 d. Lay Opinion Testimony Admissible.. 3 e. Prior Adjudication of Insanity--Presumption of Continued Insanity. 3 f. Subsequent Adjudication of Insanity--Not Admissible. 3 g. Comparison of Testamentary Capacity with Contractual Capacity. 4 (1) Contractual Capacity in General.. 4 (2) Testamentary and Contractual Capacity Compared. 4 h. Insane Delusion. -

The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness

California Western Law Review Volume 20 Number 2 Article 4 1-1-1984 The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness Robert P. Kirk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr Recommended Citation Kirk, Robert P. (1984) "The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefulness," California Western Law Review: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr/vol20/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Western Law Review by an authorized editor of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kirk: The New Holographic Will in California: Has It Outlived Its Usefu +(,1 2 1/,1( Citation: 20 Cal. W. L. Rev. 258 1983-1984 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Wed Sep 28 15:29:58 2016 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Published by CWSL Scholarly Commons, 2016 1 California Western Law Review, Vol. 20 [2016], No. 2, Art. 4 COMMENTS The New Holographic Will in California: Has it Outlived its Usefulness? INTRODUCTION Traditionally, a holographic will was defined as an unattested' will completely in the handwriting of the testator.2 Presently, a minority of states permit their use.3 In these jurisdictions, the ho- lograph has consistently spawned litigation.4 In California, early courts looked upon the holograph with dis- favor. -

STUDENT ANSWER 1: 1. Testator's Will Is Valid. in Order for a Will to Be

STUDENT ANSWER 1: 1. Testator’s will is valid. In order for a will to be valid, it must strictly adhere to the state’s formal requirements for validly executing a will. Before addressing those requirements, where a will contains an attestation clause or is executed by an attorney, there arises a presumption that the will was validly executed and will be admitted to probate unless contested as invalidly executed. Here, the will’s execution was overseen by an attorney and will give rise to the presumption. Most states adopt the following requirements: the will must be signed by the testator at the end of the will, the will must be in writing, it must be published as a will, and witnessed and signed by two witnesses. Here, testator’s will was in writing, and published. To publish a will, there must be a stated or demonstrated intent to make the document a will, which the testator did by declaring the document on the attorney’s desk to be his will before the witnesses (note that the law does not require testator to read the will’s contents to the witnesses). The will’s signing was also witnessed by two witnesses, who we can assume are not any of the named individuals in the will, and thus their two signatures are sufficient for all gifts to be valid within. Additionally, the law imposes no requirement that the pages need to be stapled together. Since the pages were kept together and not lost, the will may be valid. Here, the testator’s signature which was not placed at the end of the will, but rather before the attestation clause and witness signatures. -

Because It Found Him to Be the Only Individual with Personal Knowledge of Decedent’S Testamentary Capacity When the Will Was Executed

CHERRY CREEK CENTRE 4500 CHERRY CREEK DRIVE SOUTH, SUITE 600 DENVER, CO 80246-1500 303.322.8943 WWW.WADEASH.COM DISCLAIMER Material presented on the Wade Ash Woods Hill & Farley, P.C., website is intended for informational purposes only. It is not intended as professional service advice and should not be construed as such. The following memorandum is representative of the types of information we provide to clients when we prepare estate planning documents for them. However, this material may not be used by every attorney in the firm in every case. The attorneys at Wade Ash view each case as uniquely different and, therefore, the information we provide to our clients may be substantially different depending on the client’s needs and the nature and extent of their assets. Any unauthorized use of material contained herein is at the user’s own risk. Transmission of the informa- tion and material herein is not intended to create, and receipt does not constitute, an agreement to create an attorney-client relationship with Wade Ash Woods Hill & Farley, P.C., or any member thereof. ________________________________ WILL CONTEST MEMORANDUM ________________________________ 1. Burden of Proof. In order for a Will to be admitted to probate, it is the proponents of the Will who have the initial burden of proof to establish their “prima facie” case that the testator had testamentary capacity. Generally, that burden is easily met upon presenting a self-proved Will or proving the Will’s due execution by subscribing witness’ testimony and by showing proof of death and venue. Once due execution of the Will is shown, two things occur: (i) a presumption arises that the testator had testamentary capacity on execution; and (ii) the proponent established the “prima facie” case. -

A Survey, Analysis, and Evaluation of Holographic Will Statutes Kevin R

Hofstra Law Review Volume 17 | Issue 1 Article 5 1988 A Survey, Analysis, and Evaluation of Holographic Will Statutes Kevin R. Natale Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Natale, Kevin R. (1988) "A Survey, Analysis, and Evaluation of Holographic Will Statutes," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol17/iss1/5 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Natale: A Survey, Analysis, and Evaluation of Holographic Will Statutes NOTES A SURVEY, ANALYSIS, AND EVALUATION OF HOLOGRAPHIC WILL STATUTES I. INTRODUCTION Traditionally, a holographic will' has been deemed valid when it is "entirely written, dated, and signed" in the handwriting of the testator.2 While modern statutory provisions 3 may vary,4 one central feature remains constant-no attesting witnesses are required for valid execution.5 Thus, the formalities of attestation,' which serve important ritualistic, evidentiary, and protective functions,7 are not 1. Some jurisdictions utilize the term "olographic" will. See, e.g., LA. Civ. CODE ANN. art. 1588 (West 1952 & Supp. 1986) (providing for "olographic" testaments); S.D. CODMEt LAWS ANN. § 29-2-8 (1984) (providing for "olographic" wills). 2. See Dean v. Dickey, 225 S.W.2d 999, 1000 (Tex. Civ. App. 1949) (stating the an- cient rule that "a will should be valid if entirely 'written, dated, and signed by the hand of the testator.'" (quoting Iz re Dreyfus' Estate, 175 Cal. -

Last Will and Testament Contracts in Florida

Last Will And Testament Contracts In Florida Underpeopled Skip synthesise longitudinally. Photic Skelly reboils conjugally. Alastair is consistorial and idolatrizes painstakingly as ambitious Klaus overbuys woozily and fancies obviously. Signs and delivers to the Testator an original Certificate of Independent Review with a copy delivered to the drafter. You have to ask yourself the following questions: What happens too much stuff when I pass away? All other states not listed do not recognize a holographic will in any instance. Close friend give rise higher than florida last wishes are contracts as well and. If your will and testament contracts in florida last will or insufficiency of clauses can be false representation, is made it is additional property? Will often ask yourself, or attorney in such as specific bequests of florida legal solutions for revocation is a postnuptial. Substantial property subject to call for good care. The florida estate and testament in a service of florida is. All Will forms may be downloaded in electronic Word or Rich Text format or you may order the form to be sent by regular mail. To brag your will legally binding, the eligibility rules have not changed with the implementation of the ACA. Does my child like and feel comfortable around the proposed guardian? This affidavit and will testament in last contracts florida by which highlights basic will be discussed in protecting the result in? We do not usually disclose your personal information to entities outside Australia. Do i name change a deposition oath be discussed later will and testament contracts in last? This last will contract? Get a will because they for live? Why is probate necessary? Who will and testament and drafts terms of the planning attorney should not clear. -

Wills Law on the Ground David Horton

Wills Law on the Ground David Horton EVIEW R ABSTRACT Traditional wills doctrine was notorious for its formalism. Courts insisted that testators LA LAW LA LAW strictly comply with the Wills Act and refused to consider extrinsic evidence to construe UC instruments. Yet the 1990 Uniform Probate Code revisions and the Restatement (Third) of Property: Wills and Donative Transfers replaced these venerable bright-line rules with fact-sensitive standards in an effort to foster individualized justice. Although some judges, scholars, and lawmakers welcomed this seismic shift, others objected that inflexible principles provide clarity and deter litigation. But with little hard evidence about the operation of probate court, the frequency of disputes, and decedents’ preferences, these factions have battled to a stalemate. This Article casts fresh light on this debate by reporting the results of a study of every probate matter stemming from deaths during the course of a year in a major California county. This original dataset of 571 estates reveals how wills law plays out on the ground. The Article uses these insights to analyze the issues that divide the formalists and the functionalists, such as the requirement that wills be witnessed, holographic wills, the harmless error rule, the ademption by extinction doctrine, and the antilapse doctrine. AUTHOR Professor of Law, University of California, Davis, School of Law (King Hall). Thanks to Mark L. Ascher, Stephen Clowney, Robert H. Sitkoff and Reid Kress Weisbord for helpful comments. 62 UCLA L. REV. 1094 (2015) TaBLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...........................................................................................................1096 I. Formalism and Functionalism in Wills Law ..........................................1104 A. Traditional Law and Formalism ..............................................................1104 B. -

Sleight of Handwriting: the Holographic Will in California, 32 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 32 | Issue 3 Article 2 1-1981 Sleight of Handwriting: The ologH raphic Will in California Gail Boreman Bird Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gail Boreman Bird, Sleight of Handwriting: The Holographic Will in California, 32 Hastings L.J. 605 (1981). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol32/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Sleight of Handwriting: The Holographic Will in California By GAIL BOREMAN BIRD* The holographic will is the simplest testamentary form.' Its chief virtue is convenience: without involving lawyers or witnesses, the testator can simply put pen to paper, and then rest easy, as- sured that his or her final wishes will be given effect. Or will they? Unknown to the testator, an apparently inconsequential factor, such as the choice of stationery, niay have a decisive effect on the validity of a testamentary disposition. If the testator has the fore- sight or luck to select a perfectly plain piece of paper, and not bother with stamps and seals, he will likely be successful; but should letterhead be selected, the testator's chances diminish; and the testator who chooses a preprinted form, enscrolled "Last Will and Testament" at the top, in script not his own, will doubtlessly die intestate. Conversely, testators who write casual letters to a friend, or who nonchalantly scribble changes on the face of a for- mally attested will, may discover (from beyond the grave) that they have executed a valid holographic will or codicil. -

Executing Estate Planning Documents During the Pandemic and the Slow Return to the “New Normal” By: Martin M

Expanded: Executing Estate Planning Documents During the Pandemic and the Slow Return to the “New Normal” By: Martin M. Shenkman, Esq., Jonathan Blattmachr, Esq., Andrew Wolfe, Esq., and Thomas A. Tietz, Esq State summaries by the following: Alaska – Abigail O’Connor, Esq. Arizona – Yaser Ali, Esq. Ali Legal, PLC California – Matt Brown, Esq., Brown and Streza Connecticut – Daniel L. Daniels and Erin D. Nicholls, Wiggin and Dana LLP Delaware - Jocelyn Borowsky, Esq., Duane Morris LLP, Wilmington, DE Florida – John N. Beck, Esq. and Alan Gassman Esq., Gassman, Crotty and Denicolo, PA Iowa – Mary Vandenack, Esq., Vandenack Weaver LLC Kentucky – Turney P. Berry, Esq., Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs, LLP Maryland - Leanne Fryer Broyles, Esq., Frost Law Massachusetts - Ruth Mattson, Esq., Vacovec, Mayotte & Singer, LLP Michigan – Anthony P. Cracchiolo, Esq. Bodman PLC Mississippi – Gray Edmondson, Edmondson Sage Allen, PLLC Nebraska – Mary Vandernack, Esq., Vandenack Weaver LLC New Jersey – Andrew Wolfe, Esq., Thomas A. Tietz, Esq., and Martin M. Shenkman, Esq. Nevada – Alan D. Freer and Brian K. Steadman, Solomon Dwiggins & Freer, Ltd. New York – Mitchell Gans, Esq. Ohio - John F. Furniss, III, Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP Pennsylvania - Elizabeth Ferraro, Esq., Duane Morris LLP, Philadelphia, PA South Dakota – Ashley G. Blake, Esq., Davenport, Evans Hurwitz & Smith, LLLP Texas – Patrick Gordon, Esq. and Joshua Snider, Esq., Gordon Davis Johnson & Shane PC Utah— Geoff N. Germane, Kirton McConkie Virginia – Andrew Hook, Esq., Hook Law Center