Camp Harmony, Sone Wrote Several Letters to a Friend Describing the Living Conditions in the Camp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese American Internment: a Tragedy of War Amber Martinez Kennesaw State University

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects 4-21-2014 Japanese American Internment: A Tragedy of War Amber Martinez Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Martinez, Amber, "Japanese American Internment: A Tragedy of War" (2014). Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 604. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses and Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT: A TRAGEDY OF WAR A Reflexive Essay Presented To The Academic Faculty Amber Martinez In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies Kennesaw State University (May, 2014) 1 Japanese American internment in the United States during World War II affected thousands of lives for generations yet it remains hidden in historical memory. There have been surges of public interest since the release of the internees, such as during the Civil Rights movement and the campaign for redress, which led to renewed interest in scholarship investigating the internment. Once redress was achieved in 1988, public interest waned again as did published analysis of the internment. After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began, American pride and displays of homeland loyalty created a unique event in American history. -

Remembering 'Camp Harmony'

THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER OF THE JACL Oct. 6-19, 2017 Taiko drummers led the way to the George Tsutakawa sculpture “Harmony,” where a new sign was unveiled by Mayumi Tsutakawa. » PAGE 5 REMEMBERING » PAGE 4 California Governor ‘CAMP HARMONY’ Signs AB 491. Puyallup Valley JACL hosts the » PAGE 6 Spotlight: Race-Car 75th remembrance of the Driver Takuma Sato’s Puyallup Assembly Center. Need for Speed PHOTO: COURTESY OF PUYALLUP VALLEY JACL WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG #3308 / VOL. 165, No. 7 ISSN: 0030-8579 2 Oct. 6-19, 2017 NATIONAL HOW TO REACH US JACL Continues Opposition to Newly Issued Email: [email protected] Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 Mail: 123 Ellison S. Onizuka St., Immigration Ban Suite 313 Los Angeles, CA 90012 he JACL continues to brief to the Supreme Court (https:// STAFF oppose the Muslim country jacl.org/wordpress/wp-content/ Executive Editor travel ban. The addition of uploads/2017/09/JACL-Travel- Allison Haramoto Tthree more nations to the Muslim Ban-Amicus.pdf), the foundations Senior Editor country ban list does not alter the for this travel ban are weak at Digital & Social Media inherent flaws of the original order best, just like the case for mass in- George Johnston seeking to ban individuals based carceration of Japanese Americans ful treatment of a disfavored group. of any authority that can bring for- Business Manager Susan Yokoyama upon the majority religion of their during World War II. We call upon the courts to fulfill ward a plausible claim of an urgent their role in properly reviewing this need.” Korematsu, 323 U.S. -

Chapter 2 Background of the Monument

Chapter 2 Minidoka Internment National Monument is located in south central Idaho, approximately 15 miles northeast of Twin Falls. From 1942 to 1945, the site was a War Relocation Authority (WRA) facility, which Background of the incarcerated nearly 13,000 Nikkei (Japanese American citizens and legal resident aliens of Japanese Monument ancestry) from Washington, Oregon, California, and Alaska. Today, the 72.75-acre national monument is a small portion of the historic 33,000-acre center. The national monument site is within Idaho’s second legislative district in Jerome County and is within a sparsely populated agricultural community. The authorized boundary of the national monument is defined by the North Side Canal to the south and private property to the north and west. The Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) retains the visitor services area parcel in the center of the national monument and the east end site parcel to the east of the national monument. nized that their jobs in farming, fishing, and timber History of the Internment and offered more opportunities than in Japan. By the Incarceration of Nikkei at turn of the century there were 24,326 Issei in the U.S. with a male to female ratio of 33:1. Between Minidoka Relocation Center 1901 and 1908, 127,000 Japanese came to the U.S., including wives, picture brides, and children who eventually evened out the gender and age Pre-World War II gaps (Daniels 1962: 1, Appendix A). Nikkei com- The prelude to the incarceration began with munities developed rapidly, establishing churches, Japanese immigration and settlement of the West businesses, hotels, and schools in nihonmachi, or Coast between 1880 and 1924. -

AAPI National Historic Landmarks Theme Study Essay 10

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER ISLANDER AMERICAN PACIFIC ASIAN Finding a Path Forward ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY LANDMARKS HISTORIC NATIONAL NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY Edited by Franklin Odo Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-692-92584-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Odo, Franklin, editor. | National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.), issuing body. | United States. National Park Service. Title: Finding a Path Forward, Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study / edited by Franklin Odo. Other titles: Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study | National historic landmark theme study. Description: Washington, D.C. : National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2017. | Series: A National Historic Landmarks theme study | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017045212| ISBN 9780692925843 | ISBN 0692925848 Subjects: LCSH: National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.) | Asian Americans--History. | Pacific Islander Americans--History. | United States--History. Classification: LCC E184.A75 F46 2017 | DDC 973/.0495--dc23 | SUDOC I 29.117:AS 4 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045212 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

N Atio N a L Pa Rk S Erv Ice Interm Ou Nta in R Eg Io N 1 2795 W Est a La M

National Park Service FIRST CLASS MAIL Intermountain Region POSTAGE & FEES PAID 12795 West Alameda Parkway NATIONAL PARK SERVICE PO Box 25287 PERMIT NO. G-83 Denver, CO 80225 OFFICIAL BUSINESS PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 2015: A YEAR IN REVIEW – PRESERVING AND INTERPRETING WORLD WAR II JAPANESE AMERICAN CONFINEMENT SITES • Introduction • Overview of the Fiscal Year 2015 Grant Program Process STATUS OF FUNDING FOR THE FISCAL YEAR 2015 JAPANESE AMERICAN CONFINEMENT SITES GRANT CYCLE FISCAL YEAR 2015 GRANT AWARDS FISCAL YEAR 2015 PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS BY STATE • Arkansas • California • Colorado • District of Columbia • Hawai’i • New York • Texas • Washington • Wyoming MAP OF GRANT FUNDING BY STATE, 2009-2015 GRAPH OF GRANT FUNDING BY SITE, 2009-2015 PROJECTS COMPLETED DURING FISCAL YEAR 2015 • Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation Creates Website to Share Stories of Japanese American Detainees on Angel Island • East Bay Center for the Performing Arts Shares Hidden Legacy of Japanese Traditional Arts in New Documentary • Densho Expands Reach of Teacher Training and Enhances Online Collection with Three NPS Grants • Friends of the Texas Historical Commission, Inc., Uncovers Artifacts at Crystal City Family Internment Camp • Heart Mountain, Wyoming Foundation Extends Reach of Incarceration Story with New Website • Japanese American Citizens League’s Bridging Communities Program Expands to Chicago • Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i Uses Two NPS Grants to Engage Public with New Curriculum and Virtual Tour that Explore -

Wartime Alliances Versus Coalition Warfare How Institutional Structure Matters in the Multilateral Prosecution of Wars

ASPJ Africa & Francophonie - 3rd Quarter 2011 Wartime Alliances versus Coalition Warfare How Institutional Structure Matters in the Multilateral Prosecution of Wars DR. PATRICIA A. WEITSMAN* raffiti on the latrine walls at Kandahar airfield in Afghanistan do not make entirely clear who the enemy is. One Canadian says to the Americans, “Identify your . target before you kill.” And the response is, “Canadians, first learn how to fight and stop getting your ass kicked every time you go outside the wire.”1 Tension within the Granks is normal, especially under pressure-cooker conditions of wartime. Yet the dynamics of intracoalition and intra-alliance politics are largely ignored in advance of decisions on how to prosecute wars and in under- standing the politics of state behavior once wars are under way. This is troubling, given the importance of institutional design and its impact on fighting effectiveness. No one doubts that military alliances are highly consequential in shaping the landscape of international politics. States pursue alliances to preserve themselves in the face of threats or to augment their power. Once formed, military alliances send ripples through the system, shaping the patterns of interaction among states, and may alter the identity politics among members.2 Because of the increased threat confronting nonmembers once an alliance is formed, it may alter future patterns of alignment or culminate in military hostilities. The most consequential realm of multi- lateral action is in the area of military operations, but scholars and policy *The author is professor of political science at Ohio University. She has published numerous articles and chapters in prominent journals, newspapers, and books, and has authored, coauthored, or coedited The Politics of Policy Making in Defense and Foreign Affairs (1993); Towards a New Europe (1995); Enforcing Cooperation (1997); and Dangerous Alliances: Proponents of Peace, Weapons of War (2004). -

Historic Resource Study: Minidoka Interment Internment National

Historic Resource Study Minidoka Internment National Monument _____________________________________________________ Prepared for the National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington Minidoka Internment National Monument Historic Resource Study Amy Lowe Meger History Department Colorado State University National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Seattle, Washington 2005 Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………… i Note on Terminology………………………………………….…………………..…. ii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………. iii Part One - Before World War II Chapter One - Introduction - Minidoka Internment National Monument …………... 1 Chapter Two - Life on the Margins - History of Early Idaho………………………… 5 Chapter Three - Gardening in a Desert - Settlement and Development……………… 21 Chapter Four - Legalized Discrimination - Nikkei Before World War II……………. 37 Part Two - World War II Chapter Five- Outcry for Relocation - World War II in America ………….…..…… 65 Chapter Six - A Dust Covered Pseudo City - Camp Construction……………………. 87 Chapter Seven - Camp Minidoka - Evacuation, Relocation, and Incarceration ………105 Part Three - After World War II Chapter Eight - Farm in a Day- Settlement and Development Resume……………… 153 Chapter Nine - Conclusion- Commemoration and Memory………………………….. 163 Appendixes ………………………………………………………………………… 173 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………. 181 Cover: Nikkei working on canal drop at Minidoka, date and photographer unknown, circa 1943. (Minidoka Manuscript Collection, Hagerman Fossil -

Classroom Resources on World War Ii History and the Japanese American Experience

CLASSROOM RESOURCES ON WORLD WAR II HISTORY AND THE JAPANESE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE LIST OF RESOURCES DVDs 442: Live with Honor, Die with Dignity 97 min. 2010, UTB Pictures and Film Voice Production Documentary. Testimonies of former veterans tell the largely unknown story of unprecedented military bravery and valor of the men in the 100th Battalion/ 442nd Regimental Combat Team. They were the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in all of WWII. They were called “the Purple Heart Unit” and 21 of its members received the highest military award, the Congressional Medal of Honor. 9066 to 9/11 - 20 min 2004, Japanese American National Museum Documentary. Focuses on the World War II era treatment of Japanese Americans as seen through the contemporary lens of the post-9/11 world. This film compares the two experiences of Americans of Japanese descent during WWII and of Arab and Muslim immigrants in America today. 9066 to 9/11 (20 min) plus Something Strong Within (40 min) 2004, Japanese American National Museum This DVD combines the two documentaries on one disc. Something Strong Within - 40 min 1994, Japanese American National Museum, 369 East First Street, Los Angeles, CA Documentary. Compilation of previously unseen home movies taken by Japanese Americans in internment camps during WWII. After Silence: Civil Rights and the Japanese American Experience – 30 min. A Lois Shelton/Foxglove Films Production Bainbridge Island Historical Museum & the Washington Civil Liberties Public Education Program Suitable for Grades 7-12; College; Adult. Comes with Study Guide on inside cover. What does it mean to be an American in a time of uncertainty and fear? Based on the personal story of Dr. -

Thank You to All That Participated

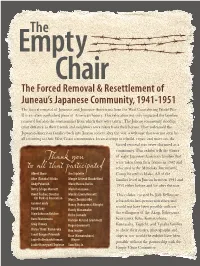

EmptyThe Chair The Forced Removal & Resettlement of Juneau’s Japanese Community, 1941-1951 The forced removal of Japanese and Japanese-Americans from the West Coast during World War II is an often overlooked piece of American history. This relocation not only impacted the families removed but also the communities from which they were taken. The Juneau community stood in quiet defiance as their friends and neighbors were taken from their homes. They welcomed the Japanese-American families back into Juneau society after the war, a welcome that was not seen by all returning to their West Coast communities. In an attempt to rebuild, repair and move on, the forced removal was never discussed as a community. This exhibit tells the stories of eight Japanese-American families that were taken from their homes in 1942 and Thank you relocated to the Minidoka Internment toAlbert all Shaw thatJim Triplette participated Camp located in Idaho. All of the Alice (Tanaka) Hikido Margie Alstead Shackelford families lived in Juneau between 1941 and Andy Pekovich Marie Hanna Darlin 1951 either before and/or after the war. Betty Echigo Marriott Mark Kanazawa Brent Fischer, Director Marsha Erwin Bennett This exhibit, curated by Jodi DeBruyne, CBJ Parks & Recreation Mary (Tanaka) Abo is based on first-person narratives and Connie Lundy Nancy (Fukuyama) Albright would not have been possible without David Gray Randy Wanamaker the willingness of the Akagi, Fukuyama, Dixie Johnson Belcher Reiko Sumada Fumi Matsumoto Karleen Alstead Grummett Kanazawa, Kito, Komatsubara, Greg Chaney Roger Grummett Kumasaka, Taguchi, and Tanaka families Haruo “Ham” Kumasaka Ron Inouye to share their stories, photographs and Janet Borgen Pekovich Rose (Komatsubara) objects; nor would the exhibit have been Janie Hollenbach Homan Wayne possible without the partnership with the Jackie Honeywell Triplette Sam Kito, Jr. -

Densho Teacher Resource Guide

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE For the Website IN THE SHADOW OF MY COUNTRY A JAPANESE AMERICAN ARTIST REMEMBERS Denshǀ: The Japanese American Legacy Project Copyright © 2003 by Denshǀ: The Japanese American Legacy Project. All rights reserved. The website In the Shadow of My Country: A Japanese American Artist Remembers (www.densho.org/shadow) and this teacher resource guide were made possible by a generous grant from the United States - Japan Foundation. This project was funded, in part, by grants from the Washington State Arts Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support for the teacher resource guide was provided by the Washington Civil Liberties Public Education Program and the Cultural Development Authority of King County "Life in Camp Harmony," from Nisei Daughter by Monica Sone, reprinted by permission from the author. Originally published in 1953 by Little Brown and Company; reprinted by University of Washington Press, 1979. Doug Selwyn and Paula Fraser acted as education consultants for this project. The lesson "Analyzing Information," Part B, is adapted from curriculum developed by Facing History and Ourselves (www.facinghistory.org) and the program Voices of Love and Freedom. Densho (meaning "to pass on to the future") is building a digital archive of life stories and historical images that document the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The archive and related curriculum on the public website (www.densho.org) promote respect for civil liberties and social justice. For more information contact: Denshǀ: The Japanese American Legacy Project 1416 South Jackson Street Seattle, WA 98144 phone: 206-320-0095 fax: 206-320-0098 email: [email protected] website: www.densho.org Cover image: Roger Shimomura, December 7, 1941, from the series An American Diary, 11 by 14 inches, acrylic on canvas, 1997. -

Japanese American Achival Collection Finding

Japanese American Archival Collection The Japanese American Archival Collection (JAAC) is comprised of 251 individual donor collections. The JAAC includes documents, publications, books, newspapers, clippings, posters, maps, photographs, artifacts, oversized items, flat file items, and framed items. There are items from the late 19th century, through World War II and the Japanese Internment camp period, up to present day objects relating to the Japanese American community. 1870 – 2015. Table of Contents Name JA # Abe, Masatoshi ………………………………………………………………………… JA 4 Akamatsu, Yasuka …………………………………………………………………….. JA 51 Akiyama, Jack ………………………………………………………………………….. JA 172 Akiyama, Onatsu ………………………………………………………………………. JA 58 Amioka, Ann ……………………………………………………………………………. JA 120 Arent, Richard ………………………………………………………………………….. JA 249 Bell, James ……………………………………………………………………………... JA 94 Bitz, Kelly ……………………………………………………………………………….. JA 220 Boardman, Daniel W. and Elizabeth …………………………………………………. JA 198 Bollinger, Margaret …………………………………………………………………….. JA 68 Bowman, Margaret …………………………………………………………………….. JA 192 Buddhist Church of Florin …………………………………………………………….. JA 80 Carey, Herbert …………………………………………………………………………. JA 79 Coombs, Robert ……………………………………………………………………….. JA 11 Craft, Charlotte ………………………………………………………………………… JA 69 Crane, Raymond ………………………………………………………………………. JA 22 CSUS …………………………………………………………………………………… JA 70 Cumpston, Frances …………………………………………………………………… JA 65 Dandelet, Lucile ……………………………………………………………………….. JA 121 Dandoy, Fujiko ………………………………………………………………………… JA 236 -

Can Topological Transitions Be Exploited to Engineer Intrinsically Quench-Resistant Wires?

Can Topological Transitions be Exploited to Engineer Intrinsically Quench-resistant Wires? Philip Whittlesea∗, Jorge Quintanillay, James F. Annettz, Adrian D. Hillierx and Chris Hooley{ ∗School of Physical Sciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NH, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] ySchool of Physical Sciences, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7NH, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] zHH Wills Physics Laboratory, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL, United Kingdom xSTFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Oxfordshire, OX11 0QX, United Kingdom {School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St Andrews, North Haugh, St Andrews KY16 9SS, United Kingdom Abstract—We investigate whether by synthesising supercon- from topological insulators to Lifshitz transitions to Majorana ductors that are tuned to a topological, node-reconstruction fermions [8]–[10], none of which can be understood purely transition point we could create superconducting wires that from a symmetry view point. It has been proposed that are intrinsically resilient to quenches. Recent work shows that the exponent characterising the temperature dependence of the topologically protected states could be usefully applied to specific heat of a nodal superconductor is lowered over a region quantum computing [11]. Here we suggest the possibility that of the phase diagram near topological transitions where nodal topological transitions in superconductors could be used to lines form or reconnect. Our idea is that the resulting enhance- make quench-resistant wires for energy transport and storage. ment of the low-temperature specific heat could have potential Unconventional superconductors can have nodal points or application in the prevention of superconductor quenches.