Music and Race in the American West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: the Politics of Reading Between East and East a Dissertati

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Queerness and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between East and East A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alvin Ka Hin Wong Committee in Charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Lowe, Co-Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Rosemary Marangoly George Professor Larissa N. Heinrich 2012 Copyright Alvin Ka Hin Wong, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Alvin Ka Hin Wong is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair ________________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………………….……………….….…iii Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………..…….…iv List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………….…........v Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………….....vi Vita …………………………………………………….…………………………….…...x Abstract of the Dissertation ………………………………………………….……….….xi INTRODUCTION.……………………………………………………………….……....1 CHAPTER ONE. Queering Chineseness and Kinship: Strategies of Rewriting by Chen Ran, Chen Xue and Huang Biyun………………………….………...33 -

JPMS3202 05 Marshall 50..62

WAYNE MARSHALL Berklee College of Music Email: [email protected] Ragtime Country Rhythmically Recovering Country’s Black Heritage ABSTRACT In 1955, Elvis Presley and Ray Charles each stormed the pop charts with songs employing the same propulsive rhythm. Both would soon be hailed as rock ’n ’roll stars, but today the two songs would likely be described as quintessential examples, respectively, of rockabilly and soul. While seeming by the mid-50s to issue from different cultural universes mapping neatly onto Jim Crow apartheid, their parallel polyrhythms point to a revealing common root: ragtime. Coming to prominence via Maple Leaf Rag (1899) and other ragtime best-sellers, the rhythm in question is exceedingly rare in the Caribbean compared to variations on its triple-duple cousins, such as the Cuban clave. Instead, it offers a distinctive, U.S.-based instantiation of Afrodiasporic aesthetics—one which, for all its remarkable presence across myriad music scenes and eras, has received little attention as an African-American “rhythmic key” that has proven utterly key to the history of American popular music, not least for the sound and story of country. Tracing this particular rhythm reveals how musical figures once clearly heard and marketed as African-American inventions have been absorbed by, foregrounded in, and whitened by country music while they persist in myriad forms of black music in the century since ragtime reigned. KEYWORDS race and ethnic studies, popular music, music history In , Elvis Presley and Ray Charles each stormed the pop charts with songs employing the same propulsive rhythm. Both would soon be hailed as rock ’n’ roll stars, but today the two songs would likely be described as quintessential examples, respectively, of rockabilly and soul. -

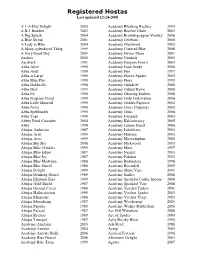

Registered Hostas Last Updated 12-24-2008

Registered Hostas Last updated 12-24-2008 A 1-A-Day Delight 2003 Academy Blushing Recluse 1999 A B-1 Bomber 2002 Academy Bonfire Glade 2003 A Big Splash 2004 Academy Brobdingnagian Viridity 2006 A Blue Streak 2001 Academy Celeborn 2000 A Lady in Blue 2004 Academy Chetwood 2005 A Many-splendored Thing 1999 Academy Cratered Blue 2008 A Very Good Boy 2005 Academy Devon Moor 2001 Aachen 2005 Academy Dimholt 2005 Aardvark 1991 Academy Fangorn Forest 2003 Abba Alive 1990 Academy Faux Sedge 2008 Abba Aloft 1990 Academy Fire 1997 Abba at Large 1990 Academy Flaxen Spades 2002 Abba Blue Plus 1990 Academy Flora 1999 Abba Dabba Do 1998 Academy Galadriel 2000 Abba Dew 1999 Academy Gilded Dawn 2008 Abba Fit 1990 Academy Glowing Embers 2008 Abba Fragrant Cloud 1990 Academy Gold Codswallop 2006 Abba Little Showoff 1990 Academy Golden Papoose 2004 Abba Nova 1990 Academy Grass Clippings 2005 Abba Spellbinder 1990 Academy Grins 2008 Abba Tops 1990 Academy Isengard 2003 Abbey Pond Cascades 2004 Academy Kakistocracy 2005 Abby 1990 Academy Lemon Knoll 2006 Abiqua Ambrosia 1987 Academy Lothlórien 2004 Abiqua Ariel 1999 Academy Mallorn 2003 Abiqua Aries 1999 Academy Mavrodaphne 2000 Abiqua Big Sky 2008 Academy Mirkwood 2003 Abiqua Blue Crinkles 1999 Academy Muse 1997 Abiqua Blue Edger 1987 Academy Nazgul 2003 Abiqua Blue Jay 1987 Academy Palantir 2003 Abiqua Blue Madonna 1988 Academy Redundant 1998 Abiqua Blue Shield 1988 Academy Rivendell 2005 Abiqua Delight 1999 Academy Shiny Vase 2001 Abiqua Drinking Gourd 1989 Academy Smiles 2008 Abiqua Elephant Ears 1999 -

Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Patricia R

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College English Faculty Publications English Department 6-9-2010 Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Patricia R. Schroeder Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/english_fac Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Patricia R., "Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race" (2010). English Faculty Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/english_fac/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Passing for Black: Coon Songs and the Performance of Race Until recently, scholars exploring blackface minstrelsy or the accompanying “coon song craze” of the 1890s have felt the need to apologize, either for the demeaning stereotypes of African Americans embedded in the art forms or for their own interest in studying the phenomena. Robert Toll, one of the first critics to examine minstrelsy seriously, was so appalled by its inherent racism that he focused his 1974 work primarily on debunking the stereotypes; Sam Dennison, another pioneer, did likewise with coon songs. Richard Martin and David Wondrich claim of minstrelsy that “the roots of every strain of American music—ragtime, jazz, the blues, country music, soul, rock and roll, even hip-hop—reach down through its reeking soil” (5). -

Bibliography

List Required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005 Updated December 15, 2010 BIBLIOGRAPHY AFGHANISTAN - BRICKS 1. Altai Consulting Group, and ILO-IPEC. A Rapid Assessment on Child Labour in Kabul. Kabul, January 2008. 2. ILO. Combating Child Labour in Asia and the Pacific: Progress and Challenges. Geneva, 2005. 3. Save the Children Sweden-Norway. "Nangarhar, Sorkrhod: Child Labor Survey Report in Brick Making." Kabul, March 2008. 4. U.S. Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2007. Washington, DC, March 11, 2008; available from http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2007/100611.htm. 5. U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report - 2006. Washington, DC, June 2006; available from http://www.state.gov/g/tip/rls/tiprpt/2006/. 6. U.S. Embassy- Kabul. reporting. December 1, 2007. 7. United Nations Foundation. U.N. Documents Child Labor Among Afghans, 2001. AFGHANISTAN - CARPETS 1. Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission. An Overview on Situation of Child Labour in Afghanistan Research Report. Kabul, 2006; available from http://www.aihrc.org.af/rep_child_labour_2006.pdf. 2. Altai Consulting Group and ILO-IPEC. A Rapid Assessment on Child Labour in Kabul. Kabul, January 2008. 3. Amnesty International. Afghanistan- Out of Sight, Out of Mind: The Fate of the Afghan Returnees. June 22, 2003; available from http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/ASA11/014/2003. 4. Chrobok, Vera. Demobilizing and Reintegrating Afghanistan’s Young Soldiers.Bonn International Center for Conversion, Bonn, 2005; available from http://www.isn.ethz.ch/isn/Digital- Library/Publications/Detail/?ots591=cab359a3-9328-19cc-a1d2- 8023e646b22c&lng=en&id=14372. -

Hiphop Aus Österreich

Frederik Dörfler-Trummer HipHop aus Österreich Studien zur Popularmusik Frederik Dörfler-Trummer (Dr. phil.), geb. 1984, ist freier Musikwissenschaftler und forscht zu HipHop-Musik und artverwandten Popularmusikstilen. Er promovierte an der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. Seine Forschungen wurden durch zwei Stipendien der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ÖAW) so- wie durch den österreichischen Wissenschaftsfonds (FWF) gefördert. Neben seiner wissenschaftlichen Arbeit gibt er HipHop-Workshops an Schulen und ist als DJ und Produzent tätig. Frederik Dörfler-Trummer HipHop aus Österreich Lokale Aspekte einer globalen Kultur Gefördert im Rahmen des DOC- und des Post-DocTrack-Programms der ÖAW. Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 693-G Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Na- tionalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http:// dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Lizenz (BY). Diese Li- zenz erlaubt unter Voraussetzung der Namensnennung des Urhebers die Bearbeitung, Verviel- fältigung und Verbreitung des Materials in jedem Format oder Medium für beliebige Zwecke, auch kommerziell. (Lizenztext: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) Die Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz gelten nur für Originalmaterial. Die Wieder- verwendung von Material aus anderen Quellen (gekennzeichnet -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

262671234.Pdf

Out of Sight Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff University Press of Mississippi / Jackson OutOut ofofOut of Sight Sight Sight The Rise of African American Popular Music – American Made Music Series Advisory Board David Evans, General Editor Barry Jean Ancelet Edward A. Berlin Joyce J. Bolden Rob Bowman Susan C. Cook Curtis Ellison William Ferris Michael Harris John Edward Hasse Kip Lornell Frank McArthur W. K. McNeil Bill Malone Eddie S. Meadows Manuel H. Peña David Sanjek Wayne D. Shirley Robert Walser Charles Wolfe www.upress.state.ms.us Copyright © 2002 by University Press of Mississippi All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 4 3 2 ϱ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abbott, Lynn, 1946– Out of Sight: the rise of African American popular music, 1889–1895 / Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff. p. cm. — (American made music series) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 1-57806-499-6 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. African Americans—Music—Hisory and criticism. 2. Popular music—United States—To 1901—History and criticism. I. Seroff, Doug. II. Title. III. Series ML3479 .A2 2003 781.64Ј089Ј96073—dc21 2002007819 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available Contents Acknowledgments ϳ Introduction ϳ Chapter 1. 1889 • Frederick J. Loudin’s Fisk Jubilee Singers and Their Australasian Auditors, 1886–1889 ϳ 3 • “Same”—The Maori and the Fisk Jubilee Singers ϳ 12 • Australasian Music Appreciation ϳ 13 • Minstrelsy and Loudin’s Fisk Jubilee Singers ϳ 19 • The Slippery Slope of Variety and Comedy ϳ 21 • Mean Judge Williams ϳ 24 • A “Black Patti” for the Ages: The Tennessee Jubilee Singers and Matilda Sissieretta Jones, 1889–1891 ϳ 27 • Other “Colored Pattis” and “Queens of Song,” 1889 ϳ 40 • Other Jubilee Singers, 1889 ϳ 42 • Rev. -

A Legacy of Hope in the Concert Spirituals Of

A LEGACY OF HOPE IN THE CONCERT SPIRITUALS OF ROBERT NATHANIEL DETT (1882-1943) AND WILLIAM LEVI DAWSON (1899-1990) A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Jeffrey Carroll Stone, II In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Major Department Music April 2017 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title A LEGACY OF HOPE IN THE CONCERT SPIRITUALS OF ROBERT NATHANIEL DETT (1882-1943) AND WILLIAM LEVI DAWSON (1899-1990) By Jeffrey Carroll Stone, II The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Dr. Michael Weber Chair Dr. JoAnn Miller Dr. Cassie Keogh Dr. Ashley Baggett Approved: April 12, 2017 Dr. JoAnn Miller Date Department Chair ABSTRACT When the careers of the composers Robert Nathaniel Dett (1882-1943) and William Levi Dawson (1899-1990) began, the United States was a racially-divided society. Despite this division, both composers held a firm belief in the potential of spirituals to bring people together. Racial segregation severely limited the civil rights of people of color; however, Dett and Dawson were fueled by the hope for spirituals to bridge the racial divide in America. Both composers desired to achieve racial equality through their music. I argue that these aspirations are embodied within their concert spirituals. This disquisition examines the legacies of Dett and Dawson for the role of “hope” in their concert spirituals. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

African and African-American Contributions to World Music

Portland Public Schools Geocultural Baseline Essay Series African and African-American Contributions to World Music by John Charshee Lawrence-McIntyre, Ph.D. Reviewed by Hunter Havelin Adams, III Edited by Carolyn M. Leonard Biographical Sketch of the Author Charshee Lawrence-Mcintyre is Associate Professor of Humanities at the State University of New York at Old Westbury in the English Language Studies Program. PPS Geocultural Baseline Essay Series AUTHOR: Lawrence-McIntyre SUBJECT: Music CONTENTS Content Page BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF THE AUTHOR.............................................................................................. I CONTENTS ..........................................................................................................................................................II INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................1 CLASSICAL AFRICA'S INFLUENCE ON OTHER CIVILIZATIONS ........................................................4 ANCIENT EGYPTIAN INSTRUMENTS .....................................................................................................................4 ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUSIC AND FORMS .............................................................................................................8 MIGRATION AND EVOLUTION OF MUSIC THROUGHOUT CONTINENTAL AFRICA ...................12 TRADITIONAL INSTRUMENTS .............................................................................................................................14 -

Ms. Jade Girl Interrupted Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ms. Jade Girl Interrupted mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Girl Interrupted Country: Europe Released: 2002 MP3 version RAR size: 1752 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1796 mb WMA version RAR size: 1348 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 111 Other Formats: AU ADX FLAC MPC MP3 AUD AHX Tracklist Hide Credits Intro 1 1:22 Voice [Vocals] – Timbaland Jade's The Champ 2 4:36 Backing Vocals – Rhonesha Howerton* She's A Gangsta 3 Arranged By [Strings], Conductor – Larry GoldBacking Vocals – TweetKeyboards – Scott 4:35 Storch The Come Up 4 Mixed By, Recorded By – Andrew Coleman Producer – The NeptunesVocals – Pharrell 4:15 WilliamsWritten-By – C. Hugo*, P. Williams* Ching Ching 5 Featuring – Nelly FurtadoRap [Vocals] – TimbalandWritten-By – B. West*, G. Mosley*, G. 3:58 Eaton*, N. Furtado* Get Away 6 Backing Vocals – Ms Jade*, Rhonesha Howerton*Featuring – Nesh*Guitar – Paul Blake 4:59 Written-By – R. Howerton* Ching Ching - Part 2 7 3:55 Backing Vocals – Ms Jade*, Raje ShwariFeaturing – Timbaland 8 Step Up 3:47 Interlude 9 1:27 Voice [Vocals] – Timbaland Count It Off 10 3:59 Backing Vocals – Rhonesha Howerton*Featuring – Jay-ZWritten-By – J. Brown*, S. Carter* Really Don't Want My Love 11 Engineer [Assistant] – Aaron FesselFeaturing – Missy ElliottWritten-By – J. Brown*, Melissa 4:13 Elliott Dead Wrong 12 4:30 Featuring – Nate DoggGuitar – Bill "Big Head" Pettaway*Written-By – N. Hale* Feel The Girl 13 4:06 Backing Vocals – TweetKeyboards – Scott Storch Big Head 14 Backing Vocals – Mary MalenaGuitar – Bill "Big Head" Pettaway*Vocals [Additional] – 3:49 Rhonesha Howerton*Written-By – R.