Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of Will Marion Cook: Materials for a Biography Peter M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

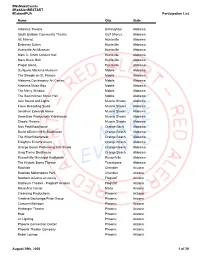

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Sudio Muscle Shoals Alabama Jonathan Edwards Home Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Bach Alabama David &DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona Herberger Theatre Phoenix -

The Leadership Issue

SUMMER 2017 NON PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL connections BALTIMORE, MD 5204 Roland Avenue THE MAGAZINE OF ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL Baltimore, MD 21210 PERMIT NO. 3621 connections THE ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL COUNTRY PARK ROLAND SUMMER 2017 LEADERSHIP ISSUE connections ROLAND AVE. TO WALL ST. PAGE 6 INNOVATION MASTER PAGE 12 WE ARE THE ROSES PAGE 16 ADENA TESTA FRIEDMAN, 1987 FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL Dear Roland Park Country School Community, Leadership. A cornerstone of our programming here at Roland Park Country School. Since we feel so passionately about this topic we thought it was fitting to commence our first themed issue of Connections around this important facet of our connections teaching and learning environment. In all divisions and across all ages here at Roland Park Country School — and life beyond From Roland Avenue to Wall Street graduation — leadership is one of the connecting, lasting 06 President and CEO of Nasdaq, Adena Testa Friedman, 1987 themes that spans the past, present, and future lives of our (cover) reflects on her time at RPCS community members. Joe LePain, Innovation Master The range of leadership experiences reflected in this issue of Get to know our new Director of Information and Innovation Connections indicates a key understanding we have about the 12 education we provide at RPCS: we are intentional about how we create leadership opportunities for our students of today — and We Are The Roses for the ever-changing world of tomorrow. We want our students 16 20 years. 163 Roses. One Dance. to have the skills they need to be successful in the future. -

SWALI.ACK-8 THEATRE. V

v NEW-YORK DAILY TRIBUNE, SUNDAY, MARCH 7, 1900. iNEVV PLAYS THIS WEEK STAGE AFFAIRS MONDAY NIGHT. NEW AMSTERDAM THEATRE ACADEMY OF MUSIC.MUSIC Bnaasi W ACADEMY Mant^li begins engagement with revival of Frederic Thompson's production at "Bre»Eter> "KingJohn." rMillions" willb* the attraction at the Academy for night. LJ- RETURN ENGAGEMENTS. X ailianii period, beginning to-morrow \u25a0-,,,: Abel** Is the chief actor In that drama It ACADEMY OF MUSlC—Edward Abelea, In " ago. and " hod to. lor.p run hi this city two \u25a0"\u25a0\u25a0 "Prewster's Millions." In other Basana fr-.r.j successful engagements WEST END THEATRE -Mr. Faversham, In parts of Use tsottntry- to-night, "The World and His \Vlf<\" Hurr Slclntosh mta give a lecture here on "Cur Country." It w!l!be amply illustrated. LEADING PERFORMERS ON VARIETY STAGE- L< ASTOR THEATRE. Hodpe as the AMERICAN MUSIC HALL—Laurenc* Irvir*. "The Man from Hcme." with Mr. play, that have In "The Kin** and the Vagabond." principal actor, is one of the few beginning of the oe*- COLONIAL THEATRE- Mny Imin. In been on the boards since the "Mr?. favorite, Caraajsa-." wn. Itis BtHIa Pscknasa'a LINCOLN SQUARE THEATRE Jarri^s J. BELASCO THEATRE. Jeffries. Bau-^ »nU The FigLtir.K Hope" are *t'.V. VICTORIA THEATRE— Eva Tanguay and JilM nc*s at the Belasco. Afternoon performs Wllla Hoit \Vaken>!d Viialar of |!m t*if< a week. t:. 2UHh performance >U 'hat drama w-i!! occur shortly. RINGLING BROTHERS' CIRCUS. BIJOU THEATRE la Another "World's Greatest Due at Those r.h. -

Hochman's Bakery ' I• Established 1920 160 CHALKSTONE AVE

Home Beautiful· Edition THE R. l. REVIEW Vol. XVII, No. 15 PROVIDENCE, R. I., JANUARY 12, 1939 5 Cents the Copy S. H. WORKMAN MAKE·s APPEAL /NOTED SCHOLAR I LEADERS TO DISCUSS \ PROBLEMS OF Almost 26 years ago, In 1914. young people who are not reached I WILL SPEAK REFUGEES a group of J ewish leaders pur-1 by the Center because of lnade- I AT CONFERENCE cbased the present building. Flor quate faclllties. I Palestine In 1938, American· Not only will hundreds of lead- many • years It was c9nducted as Furthermore, our present build· I Word has just been r eceived Jewry's role In the rebuilding of ers from scores of J ewish commu- a Hebrew school and for meeting Ing more than 70 years old, Is I nltl_es throughout the country Purposes. rapidly outliving Its usefulness that Professor Alvin S. Johnson, the Jewish National Homeland, I participate In the deliberations, In' 1925 the name was changed and Is being worn down 'by the one ' of this count~;"• great econ- and Palestine as the key to the but nation-wide broadcasts by the from the Hebrew Educational In· use made of It by many people. omists and director of the New refugee problem, will be the fun- three major radio chains will stitute to that of the Jewish Com- We are a lso concerned about the ISc hool for Social Research, has damental questions to be consld· bring to tens of tbousands of J ews munlty Center. fact that there should be neces- accepted the Invitation of the Am· ered In the sessions of the Na- and non-Jews throughout the Uni- Since that time a board of di· sary safety provisions In a publfo Ie rlcan ORT Federation to ad· tional Conference for Palestine ted Slates addresses by the prln- rectors composed of leading clti- building of this type. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS September 23, 1969 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

26744 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 23, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CHANGING CHALLENGE IN HIGH centrated on the execution of the Interstate assessing the impact of land use of highway WAY DEVELOPMENT STRESSED highway program. Before we have completed construction, urban redevelopment, mining BY SENATOR RANDOLPH IN AD it sometime in the middle of the next dec and sanitary landfills. We are looking at the DRESS AT VIRGINIA MOTOR VE ade we will have spent approximately $70 bil question of biological imbalances created by lion on this massive public works under dredging, thermal pollution, pesticides, and HICLE CONFERENCE taking, begun 48 years ago. By then we will air pollution. And we are probing problems have achieved our goal of connecting every connected with flooding and dam construc major metropolitan center in the United tion, the effects of building reservoirs, and HON. WILLIAM B. SPONG, JR. States in a coast-to-coast and border-to the use of nuclear energy for power or con OF VIRGINIA border hook-up. struction. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES In the process of building our 42,500 miles The heart of our concern is best reflected in of Interstate and Defense highways, we will Tuesday, September 23, 1969 legislation introduced early this year by have produced vast wealth in the form of myself and 41 of my colleagues, the "En Mr. SPONG. Mr. President, this morn new homes, new plants, and new jobs. We vironmental Quality Improvement Act of ing the Virginia Motor Vehicle Confer will have repeated many times over the suc 1969," which has been incorporated in S. -

Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 8-26-2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography" (2016). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 08/26/2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln This document is one in a series---"Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of"---devoted to a small number of African American musicians active ca. 1900-1950. They are fallout from my work on a pair of essays, "US Army Black Regimental Bands and The Appointments of Their First Black Bandmasters" (2013) and "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012/2016). In all cases I have put into some kind of order a number of biographical research notes, principally drawing upon newspaper and genealogy databases. None of them is any kind of finished, polished document; all represent work in progress, complete with missing data and the occasional typographical error. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

Feature Guitar Songbook Series

feature guitar songbook series 1465 Alfred Easy Guitar Play-Along 1484 Beginning Solo Guitar 1504 The Book Series 1480 Boss E-Band Guitar Play-Along 1494 The Decade Series 1464 Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series 1483 Easy Rhythm Guitar Series 1480 Fender G-Dec 3 Play-Along 1497 Giant Guitar Tab Collections 1510 Gig Guides 1495 Guitar Bible Series 1493 Guitar Cheat Sheets 1485 Guitar Chord Songbooks 1494 Guitar Decade Series 1478 Guitar Play-Along DVDs 1511 Guitar Songbooks By Notation 1498 Guitar Tab White Pages 1499 Legendary Guitar Series 1501 Little Black Books 1466 Hal Leonard Guitar Play-Along® 1502 Multiformat Collection 1481 Play Guitar with… 1484 Popular Guitar Hits 1497 Sheet Music 1503 Solo Guitar Library 1500 Tab+: Tab. Tone. Technique 1506 Transcribed Scores 1482 Ultimate Guitar Play-Along Please see the Mixed Folios section of this catalog for more2015 guitar collections. 1464 EASY GUITAR PLAY-ALONG® SERIES The Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series features 9. ROCK streamlined transcriptions of your favorite SONGS FOR songs. Just follow the tab, listen to the CD or BEGINNERS Beautiful Day • Buddy Holly online audio to hear how the guitar should • Everybody Hurts • In sound, and then play along using the back- Bloom • Otherside • The ing tracks. The CD is playable on any CD Rock Show • Use Somebody. player, and is also enhanced to include the Amazing Slowdowner technology so MAC and PC users can adjust the recording to ______00103255 Book/CD Pack .................$14.99 any tempo without changing the pitch! 10. GREEN DAY Basket Case • Boulevard of Broken Dreams • Good 1. -

Aida Overton Walker Performs a Black Feminist Resistance

Restructuring Respectability, Gender, and Power: Aida Overton Walker Performs a Black Feminist Resistance VERONICA JACKSON From the beginning of her onstage career in 1897—just thirty-two years after the end of slavery—to her premature death in 1914, Aida Overton Walker was a vaudeville performer engaged in a campaign to restructure and re-present how African Americans, particularly black women in popular theater, were perceived by both black and white society.1 A de facto third principal of the famous minstrel and vaudeville team known as Williams and Walker (the partnership of Bert Williams and George Walker), Overton Walker was vital to the theatrical performance company’s success. Not only was she married to George; she was the company’s leading lady, principal choreographer, and creative director. Moreover and most importantly, Overton Walker fervently articulated her brand of racial uplift while simultaneously executing the right to choose the theater as a profession at a time when black women were expected to embody “respectable” positions inside the home as housewives and mothers or, if outside the home, only as dressmakers, stenographers, or domestics (see Figure 1).2 Overton Walker answered a call from within to pursue a more lucrative and “broadminded” avocation—one completely outside the realms of servitude or domesticity. She urged other black women to follow their “artistic yearnings” and choose the stage as a profession.3 Her actions as quests for gender equality and racial respectability—or as they are referred to in this article, feminism and racial uplift—are understudied, and are presented here as forms of transnational black resistance to the status quo. -

African American Sheet Music Collection, Circa 1880-1960

African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1028 Extent: 6.5 linear feet (13 boxes) and 2 oversized papers boxes (OP) Abstract: Collection of sheet music related to African American history and culture. The majority of items in the collection were performed, composed, or published by African Americans. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Printed or manuscript music in this collection that is still under copyright protection and is not in the Public Domain may not be photocopied or photographed. Researchers must provide written authorization from the copyright holder to request copies of these materials. The use of personal cameras is prohibited. Source Collected from various sources, 2005. Custodial History Some materials in this collection originally received as part of the Delilah Jackson papers. Citation [after identification of item(s)], African American sheet music collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey, October 13, 2006. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Manuscript Collection No. 1028 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. -

Down Bea MUSIC '65 10Th YEARBOOK $1

down bea MUSIC '65 10th YEARBOOK $1 The Foundation Blues By Nat Hentoff Jazzmen As Critics By Leonard Feather The Academician Views De Jazz Musician ,By Malcolm E. Bessom The Jazz Musician Views The Academiciau By Marjorie Hyams Ericsson Jazz 1964: Good, Bad, Or Indifferent? Two Views Of The Year By Don DeMicheal And Tom Scanlan Articles by Stanley Dance, Vernon Duke, Don Heckman, George Hoefer, Dan Morgenstern, Pete Welding, and George Wiskirchen, C.S.C., Plus Many Other Features GUITARS Try a Harmony Soon ELECTRIC AT YOUR GUITARS gt AMPLIFIERS Favorite Music Dealer MANDOLINS BANJOS UKULELES Write for FREE full-color catalog •Address: Dept. 0Y5 Copyright 1964. The Harriony Co. Chicago 60632, U.S.A. introduces amajor current in Meateeee titiVe as COLTRANE presents SHEPP Highlighting a release of 12 distinguished new albums, is the brilliant debut A-68 J. J. JOHNSON - PROOF POSITIVE recording of ARCHIE SHEPP, who was discovered and introduced to us by A-69 YUSEF LATEEF LIVE AT PEP'S JOHN COLTRANE. We think you will agree that the young saxophonist's lucid A-70 MILT JACKSON - JAll 'N' SAMBA style and intuitive sense of interpretation will thrust him high on the list of A-71 ARCHIE SHEPP - FOUR FOR TRANE today's most influential jazz spokesmen. A-73 SHIRLEY SCOTT - EVERYBODY LOVES ALOVER A-74 JOHNNY HARTMAN - THE VOICE THAT IS As for COLTRANE himself, the 1964 Downbeat Poll's 1st place Tenor Man has A-75 OLIVER NELSON - MORE BLUES AND THE again produced a performance of unequalled distinction. ABSTRACT TRUTH Other 1st place winners represented by new Impulse albums are long-time favor- A-76 MORE OF THE GREAT LOREZ ALEXANDRIA ites J.J.