UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Lines Spring 2008

DISTRICT LINES news and views of the historic districts council spring 2008 vol. XXI no. 3 HDC Annual Conference Eyes Preservation’s Role In The Future of New York City In Ma r c h 2008, the Historic Districts neighborhoods throughout the five bor- and infrastructure concerns. Council’s 14th Annual Preservation oughs were able to admire the recently A group of respondents to the key- Conference, Preservation 2030, took a restored rotunda, built on the land where note zeroed in on PlaNYC’s lack of atten- tion to community preservation. Partici- pants included Peg Breen, president of The New York Landmarks Conservancy; Jonathan Peters, a transportation expert from the College of Staten Island; and Anthony C. Wood, author of “Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks.” “New Yorkers need more than just water to drink and beds to sleep in,” said Mr. Wood. “New York is a city of neigh- HDC Director Leo Blackman, left, moderates “Surviving the borhoods, and long-term planning for the Building Boom: Urban Neighborhoods of the Future,” featuring city has to take that into account.” Michael Rebic, Andrew Berman and Brad Lander. “Surviving the Building Boom: Urban Neighborhoods of the Future,” brought HISTORIC DISTRICTS COUNCIL together experts to discuss tools for pre- critical look at preservation’s role in shap- George Washington took his oath of serving the city’s historic urban neigh- ing New York’s urban environment for office as the first president of the United borhoods while providing new housing future generations. Rather than lament- States. -

Csoa-Announces-November-2020

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: October 22, 2020 Eileen Chambers 312-294-3092 Dana Navarro 312-294-3090 CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ASSOCIATION ANNOUNCES NOVEMBER 2020 DIGITAL PROGRAMS Highlights include Two New Episodes of CSO Sessions, Free Thanksgiving Day Digital Premiere of CSO/Solti Beethoven Fifth Symphony Archival Broadcast, Veteran’s Day Tribute Program from CSO Trumpet John Hagstrom, and More CSO Sessions Episode 7 features Former Solti Conducting Apprentice Erina Yashima Leading Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale with Actor James Earl Jones II New On-Demand Recital from Symphony Center Presents features Pianist Jorge Federico Osorio NOVEMBER 5-29 CHICAGO—The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association (CSOA) announces details for its November 2020 digital programs that provide audiences both locally and around the world a way to connect with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra online. Highlights include the premiere of two new episodes in the CSO Sessions series, two archival CSO television broadcast programs, a new piano recital from Symphony Center Presents and a Veteran’s Day digital premiere of a tribute to veterans that highlights the trumpet’s key role in military and orchestral music. Programs will be available via CSOtv, the new video portal for free and premium on-demand videos. A chronological list of November 2020 digital programs is available here. CSO Sessions The new digital series of on-demand, high-definition video recordings of chamber music and chamber orchestra concerts feature performances by Chicago Symphony Orchestra musicians filmed in Orchestra Hall at Symphony Center. Programs for the CSO Sessions series are developed with artistic guidance from Music Director Riccardo Muti. -

William Burnet Tuthill Collection

WILLIAM BURNET TUTHILL COLLECTION William Burnet Tuthill Collection Guide Overview: Repository: Inclusive Dates: Carnegie Hall Archives – 1891 - 1920 Storage Room Creator: Extent: William Burnet Tuthill 1 box, 42 folders; 1 Scrapbook (10 X 15 X 3.5), 5 pages + 1 folder; 44 architectural drawings Summary / Abstract: William Burnet Tuthill is the architect of Carnegie Hall. He was an amateur cellist, the secretary of the Oratorio Society, and an active man in the music panorama of New York. The Collection includes the questionnaires he sent to European theaters to investigate about other theaters and hall, a scrapbook with clippings of articles and lithographs of his works, and a series of architectural drawings for the Hall and its renovations. Access and restriction: This collection is open to on-site access. Appointments must be made with Carnegie Hall Archives. Due to the fragile nature of the Scrapbook, consultation could be restricted by archivist’s choice. To publish images of material from this collection, permission must be obtained in writing from the Carnegie Hall Archives Collection Identifier & Preferred citation note: CHA – WBTC – Q (001-042) ; CHA – WBTC – S (001-011) ; CHA – AD (001-044) William Burnet Tuthill Collection, Personal Collections, Carnegie Hall Archives, NY Biography of William Burnet Tuthill William Burnet Tuthill born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1855. He was a professional architect as well as passionate and amateur musician, a good cellist, and an active man in the music scene of New York. He studied at College of the City of New York in 1875 and after receiving the Master of Arts degree, started his architectural career in Richard Morris Hunt’s atelier (renowned architect recognized for the main hall and the façade of the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue, the Charity Home on Amsterdam Avenue – now the Hosteling International Building- and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty). -

Mark Seto New Director of Orchestra at Brown University

Brown University Department of Music Box 1924, Providence, RI 02912 Press Contact Drew Moser / 401-863-3236 Academic Program & Outreach Coordinator May 10, 2018 / For Immediate Release Mark Seto Hired as the New Director of the Brown University Orchestra Providence, RI—The Department of Music is proud to announce conductor, musicologist, and violinist Mark Seto as Director of the Brown University Orchestra effective July 1, 2018. In addition to bringing his vast experience as an educator and orchestra director to the classroom and stage, Seto will assist in the development of Brown’s new Performing Arts Center. Seto comes directly from Connecticut College where he was Associate Professor of Music and director of the Connecticut College Orchestra. He also holds the position of Artistic Director and Conductor of The Chelsea Symphony in New York City. Seto earned a BA in Music from Yale University and an MA, MPhil, and PhD in Historical Musicology from Columbia University. About Mark Seto Mark Seto leads a wide-ranging musical life as a conductor, musicologist, teacher, and violinist. In addition to his new appointment at Brown University, he continues as Artistic Director and Conductor of The Chelsea Symphony in New York City. At Connecticut College, Seto directed the faculty ensemble and the Connecticut College Orchestra, and taught music history, theory, conducting, and orchestration. During Seto’s tenure at Connecticut, he helped double student enrollment in the orchestra. Furthermore, the ensemble assumed a greater role in the College’s cultural and intellectual life. Seto aimed to connect the learning he and his ensembles undertook in rehearsal to themes that resonate with them as engaged global and local citizens. -

Elevator Interior Design

C AMB RIDGE A select portfolio of architectural mesh projects for new or refurbished elevator cabs, lobbies and high-traffic spaces featuring Cambridge’s metal mesh. ARCHITECTURAL MESH Beautiful, light-weight and durable, architectural mesh has been prized by architects and designers since we first wove metal fabric for the elevator cabs in Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in 1958. And it’s still there today. Learn more about our elite line of elegant panels in stainless steel, brass, copper and aluminum. Carnegie Hall, New York City Elegant burnished aluminum panels lift Carnegie Hall’s elevator interiors to another level. Installed by EDI/ECI in concert with Iu + Biblowicz Architects, Comcast Center, Philadelphia, PA Cambridge’s Sawgrass pattern adds When designing the a refined and resilient interior to world’s tallest green this refurbished masterpiece. building, Robert A.M. © Gbphoto27 | Dreamstime.com Stern Architects added style and sustainability with Empire State Building, Cambridge mesh. New York City Classically outfitted Beyer, Blinder & with the chic Ritz pattern, the flexible Belle Architects stainless steel fabric integrates the modernized the lobby and elevators with a smooth landmark and seamless design. skyscraper’s elevator cabs with Cambridge’s Stipple mesh. Installed by the National Elevator Cab & Door Co., the dappled brushed aluminum surface stands up to the traffic and traditions of this legendary building. Victory Plaza, Dallas, TX TFO Architecture’s YAHOO!, Sunnyvale, CA expansive mixed-use project in the center Gensler architects of downtown selected Cambridge’s incorporates one of Silk mesh to clad Cambridge’s most elevators at Yahoo’s popular rigid mesh Silicon Valley fabrics. -

Cororio Carnegie Hall / New York City Tour May 22 – 26, 2018

CoroRio Carnegie Hall / New York City Tour May 22 – 26, 2018 Round Trip Airfare from Memphis to New York City (pricing updated 9/10/17) Round Trip Ground Transportation to/from Airport and Hotel in New York City PERFORMANCE with DCINY at Carnegie Hall (performers)** Four Nights’ Accommodations at a Midtown Manhattan Hotel** Three Group Dinners ~ Two Sightseeing Attractions ~ One Broadway Show ~ One 4-Trip Metro Card** Orchestra Level Concert Seating and POST CONCERT RECEPTION for all Performers and VIP Patrons** All taxes, gratuities and mandatory fees** **Inclusions in the Land only package Prices are per person DCINY Registration Type** Quad Triple Double Single Air & Land Performer $ 2015.00 $ 2140.00 $ 2385.00 $ 3020.00 Air & Land VIP Patron (Non-Performer) $ 1520.00 $ 1645.00 $ 1890.00 $ 2525.00 Air & Land Concert Attendee $ 1205.00 $ 1330.00 $ 1575.00 $ 2210.00 Land Only Performer $ 1665.00 $ 1790.00 $ 2035.00 $ 2670.00 Land Only VIP Patron (Non-Performer) $ 1170.00 $ 1295.00 $ 1540.00 $ 2175.00 Land Only Concert Attendee $ 855.00 $ 980.00 $ 1225.00 $ 1860.00 **DCINY Registration Inclusions: All students are required to purchase the Performer package. VIP Patrons are admitted to all rehearsals, including dress rehearsals in Carnegie Hall, and receive orchestra level concert seating and admission to the post concert reception for all performers & directors. Parents who are accompanying their singer are encouraged to be VIP Patrons (at least one per family). Concert attendee cost includes $80 for an orchestra level concert seat with the rest of the group. Note: The above prices include DCINY Performer Fee of $790.00 and DCINY VIP fee of $395.00, all hotel taxes, mandatory baggage handling fee at hotel (one suitcase per person), gratuities and service charges. -

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

The Seagram Building, Designed by Mies Van Der Rohe, Continues To

The Seagram Building, designed by Mies van der Rohe, continues to receive acclaim as New York’s most prestigious office building and the finest example of modern American architecture. We are proud to own this great asset and are committed to ensuring that this Landmark building offers the utmost standards of excellence and service to all of our tenants. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 30 31 32 33 375 Park Avenue is widely recognized as building was the first skyscraper in New one of the iconic structures of post-World York City to use floor-to-ceiling plate glass. War II International Style architecture, and is The glazing system in turn required special among the most significant works of Ludwig mechanical innovations such as a specially Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson, two designed peripheral air conditioning system of the most important architects of the 20th consisting of low modular units, which would century. From the time of its completion, the cool the building without obstructing views. building has been hailed as one of the most important works of American architecture. The New York Times called it “one of the most notable of Manhattan’s post-war buildings,” At the time of construction, the Seagram and said of the plaza that it had become Building set the gold standard for post- “an oasis for office workers and passersby.” war corporate architecture in America. The In addition to critical praise, the Seagram influence of the building on the course of Building and its architects received a American architecture can be seen up number of awards. -

A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE to BROOKLYN Judith E

L(30 '11 II. BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Edward I. Koch, Hon. Howard Golden, Seth Faison, Paul Lepercq, Honorary Chairmen; Neil D. Chrisman, Chairman; Rita Hillman, I. Stanley Kriegel, Ame Vennema, Franklin R. Weissberg, Vice Chairmen; Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Chief Executive Officer; Harry W. Albright, Jr., Henry Bing, Jr., Warren B. Coburn, Charles M. Diker, Jeffrey K. Endervelt, Mallory Factor, Harold L. Fisher, Leonard Garment, Elisabeth Gotbaum, Judah Gribetz, Sidney Kantor, Eugene H. Luntey, Hamish Maxwell, Evelyn Ortner, John R. Price, Jr., Richard M. Rosan, Mrs. Marion Scotto, William Tobey, Curtis A. Wood, John E. Zuccotti; Hon. Henry Geldzahler, Member ex-officio. A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE TO BROOKLYN Judith E. Daykin Executive Vice President and General Manager Richard Balzano Vice President and Treasurer Karen Brooks Hopkins Vice President for Planning and Development IN HONOR OF THE 100th ANNIVERSARY Micheal House Vice President for Marketing and Promotion ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE STAFF OF THE Ruth Goldblatt Assistant to President Sally Morgan Assistant to General Manager David Perry Mail Clerk BROOKLYN BRIDGE FINANCE Perry Singer Accountant Tuesday, November 30, 1982 Jack C. Nulsen Business Manager Pearl Light Payroll Manager MARKETING AND PROMOTION Marketing Nancy Rossell Assistant to Vice President Susan Levy Director of Audience Development Jerrilyn Brown Executive Assistant Jon Crow Graphics Margo Abbruscato Information Resource Coordinator Press Ellen Lampert General Press Representative Susan Hood Spier Associate Press Representative Diana Robinson Press Assistant PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Jacques Brunswick Director of Membership Denis Azaro Development Officer Philip Bither Development Officer Sharon Lea Lee Office Manager Aaron Frazier Administrative Assistant MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Jack L. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

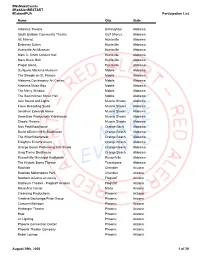

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Sudio Muscle Shoals Alabama Jonathan Edwards Home Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Bach Alabama David &DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona Herberger Theatre Phoenix