Brett Sheehy CONFESSIONS of a GATEKEEPER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Development Approved Applications February 2014 Summary of Development Approved Applications February 2014

Summary of Development Approved Applications February 2014 Summary of Development Approved Applications February 2014 Printed - 11/03/2014 10:13:47 AM Application 1: DA / 543 / 2013 / A / 1 Lodged: 21/02/2014 Description: Vary previous authorisation to carry out internal and external alterations and change the use from office to licensed premises with entertainment including signage - VARIATION - To permit the development to be undertaken in stages - Stage 1 - building modifications and use of premises (without music entertainment after 10pm)Stage 2 - Use of premises with music entertainment after 10pm **STAGE 1 ONLY** Property Address: Mr Goodbar Applicant : FUNDAMENTAL FLOW P/L 12-16 Union Street ADELAIDE SA 5000 Owner : Ms E Duff-Tytler Estimated Cost of Dev: To Be Advised Private Certifier : PBS AUSTRALIA P/L Consent: Development Approval Decision: Development Approval Granted Authority: Delegated to Administration Date: 27/02/2014 CITB Reference: 52739 Application 2: DA / 133 / 2014 Lodged: 21/02/2014 Description: Tenancy fitout (Chinese BBQ cafe) Property Address: 29 Field Street Applicant : BOCLOUD INTERNATIONAL ADELAIDE SA 5000 Owner : Mr C Karapetis Estimated Cost of Dev: $11,500 Private Certifier : BUILDING CERTIFICATION APPROVALS (SA) P/L Consent: Development Approval Decision: Development Approval Granted Authority: Delegated to Administration Date: 25/02/2014 CITB Reference: Application 3: DA / 132 / 2014 Lodged: 19/02/2014 Description: Shop fitout Property Address: La Vie En Rose - G.06 Applicant : CHECKPOINT Ground 77-91 Rundle Mall ADELAIDE SA 5000 Owner : ALTEMAN (SA) P/L Estimated Cost of Dev: $200,000 Private Certifier : PBS AUSTRALIA P/L Consent: Development Approval Decision: Development Approval Granted Authority: Delegated to Administration Date: 21/02/2014 CITB Reference: 52617 Application 4: DA / 131 / 2014 Lodged: 20/02/2014 Description: Erect wrap around temporary fencing 24/2/14 to 1/3/14. -

Af20-Booking-Guide.Pdf

1 SPECIAL EVENT YOU'RE 60th Birthday Concert 6 Fire Gardens 12 WRITERS’ WEEK 77 Adelaide Writers’ Week WELCOME AF OPERA Requiem 8 DANCE Breaking the Waves 24 10 Lyon Opera Ballet 26 Enter Achilles We believe everyone should be able to enjoy the Adelaide Festival. 44 Between Tiny Cities Check out the following discounts and ways to save... PHYSICAL THEATRE 45 Two Crews 54 Black Velvet High Performance Packing Tape 40 CLASSICAL MUSIC THEATRE 16 150 Psalms The Doctor 14 OPEN HOUSE CONCESSION UNDER 30 28 The Sound of History: Beethoven, Cold Blood 22 Napoleon and Revolution A range of initiatives including Pensioner Under 30? Access super Mouthpiece 30 48 Chamber Landscapes: Pay What You Can and 1000 Unemployed discounted tickets to most Cock Cock... Who’s There? 38 Citizen & Composer tickets for those in need MEAA member Festival shows The Iliad – Out Loud 42 See page 85 for more information Aleppo. A Portrait of Absence 46 52 Garrick Ohlsson Dance Nation 60 53 Mahler / Adès STUDENTS FRIENDS GROUPS CONTEMPORARY MUSIC INTERACTIVE Your full time student ID Become a Friend to access Book a group of 6+ 32 Buŋgul Eight 36 unlocks special prices for priority seating and save online and save 15% 61 WOMADelaide most Festival shows 15% on AF tickets 65 The Parov Stelar Band 66 Mad Max meets VISUAL ART The Shaolin Afronauts 150 Psalms Exhibition 21 67 Vince Jones & The Heavy Hitters MYSTERY PACKAGES NEW A Doll's House 62 68 Lisa Gerrard & Paul Grabowsky Monster Theatres - 74 IN 69 Joep Beving If you find it hard to decide what to see during the Festival, 2020 Adelaide Biennial . -

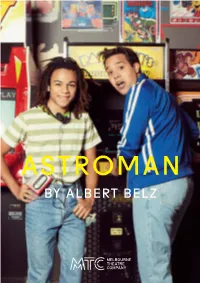

ASTROMAN by ALBERT BELZ Welcome

ASTROMAN BY ALBERT BELZ Welcome Over the course of this year our productions have taken you to London, New York, Norway, Malaysia and rural Western Australia. In Astroman we take you much closer to home – to suburban Geelong where it’s 1984. ASTROMAN In this touching and humorous love letter to the 80s, playwright Albert Belz wraps us in the highs and lows of growing up, the exhilaration of learning, and what it means to be truly courageous. BY ALBERT BELZ Directed by Sarah Goodes and Associate Director Tony Briggs, and performed by a cast of wonderful actors, some of them new to MTC, Astroman hits the bullseye of multigenerational appeal. If ever there was a show to introduce family and friends to theatre, and the joy of local stories on stage – this is it. At MTC we present the very best new works like Astroman alongside classics and international hits, from home and abroad, every year. As our audiences continue to grow – this year we reached a record number of subscribers – tickets are in high demand and many of our performances sell out. Subscriptions for our 2019 Season are now on sale and offer the best way to secure your seats and ensure you never miss out on that must-see show. To see what’s on stage next year and book your package visit mtc.com.au/2019. Thanks for joining us at the theatre. Enjoy Astroman. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the First Peoples of Country on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to all of Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. -

Florian Zeller Christopher Hampton

THE TRUTH BY Florian Zeller TRANSLATED BY Christopher Hampton DIRECTED BY Sarah Giles Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the First Peoples of Country on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand. We pay our respects to all of Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. WELCOME Florian Zeller is a name familiar to MTC audiences after our 2017 co-production of his play, The Father. Since then his star has been continuously on the rise and saw the film adaption of that play take home this year’s Academy Awards for Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actor. Another of his plays is currently receiving a film adaptation as well. Zeller is a towering talent and The Truth reinforces his deft skill of drawing audiences into layered stories which are never as straightforward as they appear. We are thrilled to be producing this play in its English translation by Zeller’s long-time collaborator and co-Academy Award-winner, Christopher Hampton. In The Truth, comedy shines through the underlying bed of deception and marital manipulations, and with a cast featuring the comic pedigree of Michala Banas, Stephen Curry, Bert LaBonté and Katrina Milosevic you really are set for an enjoyable night at the theatre. Directed by Sarah Giles, this production is the fourth Australian premiere in our 2021 program, and the second in our Act 2 suite of six productions. The Truth and other international works are beautifully complemented by an array of new Australian plays being presented in the months ahead. -

National Theatre

WITH EMMA BEATTIE OLIVER BOOT CRYSTAL CONDIE EMMA-JANE GOODWIN JULIE HALE JOSHUA JENKINS BRUCE MCGREGOR DAVID MICHAELS DEBRA MICHAELS SAM NEWTON AMANDA POSENER JOE RISING KIERAN GARLAND MATT WILMAN DANIELLE YOUNG 11 JAN – 25 FEB 2018 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE Presented by Melbourne Theatre Company and Arts Centre Melbourne This production runs for approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes, including a 20 minute interval. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is presented with kind permission of Warner Bros. Entertainment. World premiere: The National Theatre’s Cottesloe Theatre, 2 August 2012; at the Apollo Theatre from 1 March 2013; at the Gielgud Theatre from 24 June 2014; UK tour from 21 January 2017; international tour from 20 September 2017 Melbourne Theatre Company and Arts Centre Melbourne acknowledge the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the Traditional Owners of the land on which this performance takes place, and we pay our respects to Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors past and present, and to our shared future. DIRECTOR MARIANNE ELLIOTT DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER VIDEO DESIGNER BUNNY CHRISTIE PAULE CONSTABLE FINN ROSS MOVEMENT DIRECTORS MUSIC SOUND DESIGNER SCOTT GRAHAM AND ADRIAN SUTTON IAN DICKINSON STEVEN HOGGETT FOR AUTOGRAPH FOR FRANTIC ASSEMBLY ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR RESIDENT DIRECTOR ELLE WHILE KIM PEARCE COMPANY VOICE WORK DIALECT COACH CASTING CHARMIAN HOARE JEANNETTE NELSON JILL GREEN CDG The Cast Christopher Boone JOSHUA JENKINS SAM NEWTON* Siobhan JULIE HALE Ed DAVID MICHAELS Judy -

Country Arts SA Brings Biggest Season Yet to the Riverland

April 2017 Adelaide Cabaret Festival Roadshow is back - direct from the world’s best and biggest cabaret festival! Adelaide Festival Centre and Country Arts SA present Adelaide Cabaret Festival Roadshow, a spectacular variety evening of hand-picked sequined talent. Each year, Adelaide Cabaret Festival gathers artists from all over the world for 16 revolutionary nights. Featuring some of the most outrageous, raw, fierce (and fun!) performances around, Adelaide Cabaret Festival Roadshow brings festival favourites to you. Supported by a great band and the vivacious Eddie Bannon who will return for his third year hosting Adelaide Cabaret Festival Roadshow, artists performing include South Australian burlesque star Sapphire Snow, Cameron Goodall, Melissa Langton, Mark Jones, and the irreverent Tripod. Prepare yourself for a night of amazing musical prowess, impeccable comedic timing, and captivating characters. This is also your chance to experience the best emerging young talent from your region. The local Nathaniel O’Brien Class of Cabaret Scholarship recipient will grace the stage to impress and inspire. Adelaide Cabaret Festival Regional Roadshow is an annual event held in the lead up to Adelaide Cabaret Festival. The Roadshow brings renowned Australian cabaret artists to different regions in South Australia giving locals a taste of what the Festival offers. Expect unforgettable performances from some of the best cabaret artists around. Paul Roberts, spokesperson for Country Arts SA’s principal corporate partner SA Power Networks said: “The Adelaide Cabaret Festival Roadshow is a great night out. Book a table with friends and join in a gala evening that you won't forget!" Look out for an Adelaide Cabaret Festival car chock-full of cabaret artists heading to a region near you. -

ACCESS GUIDE Contents

26 FEB – 14 MAR 2021 ACCESS GUIDE Contents Access Information ................................................................. 1 Website Information ................................................................. 2 Booking Tickets ........................................................................... 3 Venue Facilities ........................................................................... 4 Access Ticket Prices ................................................................. 5 Auslan Interpreted Events ....................................................... 6 Audio Described Events ......................................................... 8 Sensory/Tactile Tour Events ............................................... 9 Events With Highly Visual Content ................................... 10 Events With Assistive Listening ............................................. 13 Venues With Wheelchair Access ............................................. 15 Open House ..................................................................................... 19 Adelaide Writers’ Week Access ............................................. 21 Calendar of Events ................................................................. 22 Map ............................................................................................... 25 Sponsor Thanks ........................................................................... 27 Access Information We make every effort to ensure Adelaide Festival events are accessible to our whole audience. Please check -

2022 Adelaide Festival Awards for Literature Guidelines

ADELAIDE FESTIVAL AWARDS FOR LITERATURE 2022 GUIDELINES ADELAIDE FESTIVAL AWARDS FOR LITERATURE 2022 CONTENTS About the Awards 3 2022 National Awards for Published Works 4 2022 Awards for South Australian Writers 5 2022 Fellowships for South Australian Writers 6 How to Apply 7 Opening date March 2021 Closing date 5.00pm, Wednesday 30 June 2021 ADELAIDE FESTIVAL AWARDS FOR LITERATURE 2 ABOUT THE AWARDS The Adelaide Festival Awards for Literature (AFAL) are presented every two years during Adelaide Writers’ Week as part of the Adelaide Festival. Introduced in 1986 by the Government of South Australia, the awards celebrate South Australia’s writing culture by offering national and State-based literary prizes, as well as fellowships for South Australian writers. The awards are managed by the State Library of South Australia. The awards provide an opportunity to highlight the importance of our unique South Australian writers and contribute to and support community engagement with literature. Award winners will be invited to attend the award presentation. The State Library will arrange for interstate/intrastate return economy airfares to Adelaide, two nights accommodation, and transport to and from the airport for winning authors to attend the award presentation to be held during Writers’ Week in March 2022. Nominations for the 2022 Adelaide Festival Awards for Literature will close on Wednesday 30 June 2021. • Entries are acknowledged within one month of receipt. • Incomplete or late nominations will not be accepted. • Any breach of nomination conditions will render a nomination invalid. • Nominated publications will not be returned after the judging process. Publications will be added to the State Library Collection. -

A Christmas Celebration

A Christmas Celebration 10-12 December Festival Theatre A Christmas Celebration Welcome Luke Dollman Conductor It would be a joy to present this concert for you at the Mitchell Butel MC/Vocals/Creative Director end of any year, but right now that joy is tinged with Johanna Allen Vocals an awareness of what a challenging journey 2020 has The Idea of North Vocal quartet been. This is a season to be especially grateful that Freddy Ramly-Peck The Little Drummer Boy we are together again, in the company of the ASO, Mietta Brookman The Sugar Plum Fairy conductor Luke Dollman and the wonderful artists who will bring you magical Christmas entertainment. Duration Approx. 1 hr 20 mins, no interval 2020 has been a test of resilience, and a test of inventiveness too. Although the possibility of live performance evaporated in March, the ASO quickly GRUBER recognised the opportunities the online space Silent Night presented, and since then the musicians have kept the music-making alive through a series of virtual HURST concerts. Your response to these performances has A Welcome to Christmas been tremendously encouraging and you will see on the ASO website that new online performances GILLESPIE/COOTS (arr. YOUNG) continue to be available to you. Santa Claus is Coming to Town Adelaide Festival Centre took the first careful steps CAPPEAU/ADAM towards bringing live music back after the shutdowns, O Holy Night with a series of concerts at the redeveloped Her Majesty’s Theatre, and has continued to pioneer the HAIRSTON ( arr. TWIST) safe return of artists and audiences to venues. -

Fulltimeoperationsince1996

| 23 is 10! | Welcome to a celebration of our 10th birthday. First a word from Tony MacGregor, Chair of the Open City Board of Management. This company was established by Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter in 1987 for the collaborative works they performed in theatres, galleries and on radio. In 1994 Open City began to publish RealTime+OnScreen which has been a fulltime operation since 1996. FROM THE CHAIR I’ve been free-associating around those words—real, time—looking for a RT61 JUNE / JULY 04 way into writing about this thing I’ve been hovering around for these past 10 years. Longer really, because RealTime was an idea long before it was a reality, one of those determinations that Keith Gallasch and Virginia Baxter make and then work into existence: “mainstream theatre criticism is hopeless, we need a journal that deals properly with the per- formance community in all its hybrid, messy complexity.” (Or words to that effect.) And, lo, it was so. How many ideas have taken shape, been given form in the endless conversa- tion around that generous wooden table in the kitchen at Womerah Avenue, Darlinghurst where Gallasch and Baxter have lived since their arrival from Adelaide in 1986? Like so many projects which have been founded on their energy and ideas—Troupe in Adelaide, Open City, all those performances—once deemed A Good Idea, RealTime seemed inevitable, an idea made real through that seemingly irresistible combination of clear argument, creative invention, per- sonal passion, A-grade grant writing The RealTime team: Keith Gallasch, Dan Edwards, Gail Priest, Virginia Baxter Heidrun Löhr skills and the sheer bloody mindedness that they bring to all their projects. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Learning to Inhabit the Chair Knowledge transfer in contemporary Australian director training Christopher David Hay A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Performance Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney May 2014 Labour is blossoming or dancing where The body is not bruised to pleasure soul, Nor beauty born out of its own despair, Nor blear-eyed wisdom out of midnight oil. -

Womadelaide 1992 – 2016 Artists Listed by Year/Festival

WOMADELAIDE 1992 – 2016 ARTISTS LISTED BY YEAR/FESTIVAL 2016 47SOUL (Palestine/Syria/Jordan) Ainslie Wills (Australia) Ajak Kwai (Sudan/Australia) All Our Exes Live in Texas (Australia) Alpine (Australia) Alsarah & the Nubatones (Sudan/USA) Angelique Kidjo (Benin) & the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (Australia) APY Choir (Australia) Asha Bhosle (India) Asian Dub Foundation (UK) Australian Dance Theatre “The Beginning of Nature” (Australia) Calexico (USA) Cedric Burnside Project (USA) DakhaBrakha (Ukraine) Datakae – Electrolounge (Australia) De La Soul (USA) Debashish Bhattacharya (India) Diego el Cigala (Spain) Djuki Mala (Australia) Edmar Castañeda Trio (Colombia/USA) Eska (UK) – one show with Adelaide [big] String Ester Rada (Ethiopia/Israel) Hazmat Modine (USA) Husky (Australia) Ibeyi (Cuba/France) John Grant (USA) Kev Carmody (Australia) Ladysmith Black Mambazo (South Africa) Mahsa & Marjan Vahdat (Iran) Marcellus Pittman - DJ (USA) Marlon Williams & the Yarra Benders (NZ/Australia) Miles Cleret - DJ (UK) Mojo Juju (Australia) Mortisville vs The Chief – Electrolounge (Australia) Mountain Mocha Kilimanjaro (Japan) NO ZU (Australia) Orange Blossom (France/Egypt) Osunlade - DJ (USA) Problems - Electrolounge (Australia) Quarter Street (Australia) Radical Son (Tonga/Australia) Ripley (Australia) Sadar Bahar - DJ (USA) Sampa the Great (Zambia/Australia) Sarah Blasko (Australia) Savina Yannatou & Primavera en Salonico (Greece) Seun Kuti & Egypt 80 (Nigeria) Songhoy Blues (Mali) Spiro (UK) St Germain (France) Surahn (Australia) Tek Tek Ensemble