Towards a Cultural Policy for Great Events P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES Senate Official Hansard No. 5, 2005 TUESDAY, 8 MARCH 2005 FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE SENATE INTERNET The Journals for the Senate are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/work/journals/index.htm Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2005 Month Date February 8, 9, 10 March 7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17 May 10, 11, 12 June 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23 August 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 September 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 October 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13 November 7, 8, 9, 10, 28, 29, 30 December 1, 5, 6, 7, 8 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM GOSFORD 98.1 FM BRISBANE 936 AM GOLD COAST 95.7 FM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 747 AM NORTHERN TASMANIA 92.5 FM DARWIN 102.5 FM FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—SECOND PERIOD Governor-General His Excellency Major-General Michael Jeffery, Companion in the Order of Australia, Com- mander of the Royal Victorian Order, Military Cross Senate Officeholders President—Senator the Hon. Paul Henry Calvert Deputy President and Chairman of Committees—Senator John Joseph Hogg Temporary Chairmen of Committees—Senators the Hon. -

Sydney Peace Foundation Annual Report 2011

Annual Report 2011 Professor Noam Chomsky, 2011 Sydney Peace Prize Recipient Contents 2 Message from the Governer 3 Letter from the Lord Mayor of Sydney 4 Sydney Peace Foundation Profile 5 Commitee Members and Staff 6 Chair’s Report 9 Director’s Report 14 Sydney Peace Prize 16 Images of 2011 20 Youth Peace Initiative Report 22 2011 Sydney Peace Foundation Donors 23 Financial Report 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | 1 2 | THE SYDNEY PEACE FOUNDATION 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | 3 Peace with justice is a way of thinking and acting which promotes non-violent solutions to everyday problems and provides the foundations of a civil society. The Foundation Why is Peace with Justice • awards the Sydney Peace Prize Important? • develops corporate sector and community • it provides for the security of children understanding of the value of peace with justice • it envisages an end to the violence of poverty • supports the work of the Centre for Peace and • it paints a vision of individual and community Conflict Studies fulfilment through the creation of rewarding • Encourages and recognises significant opportunities in education and employment contributions to peace by young people through The Sydney Peace Foundation is a privately the Youth Peace Initiative endowed Foundation established in 1998 within the University of Sydney Post-graduate students at the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies who were indispensable in the running of the 2011 Sydney Peace Prize Gala Dinner. 4 | THE SYDNEY PEACE FOUNDATION The Sydney Peace Foundation Commitee Members Chair Foundation Council Advisory Committee Ex Officio members Ms Beth Jackson Mr Alan Cameron AM Vice Chancellor Dr Michael Ms Penny Amberg Spence Director The Hon. -

Chief Executive's Review

ANNUAL REPORT 2010-2011 Department of the Premier and Cabinet State Administration Centre 200 Victoria Square Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 2343 Adelaide SA 5001 ISSN 0816‐0813 For copies of this report please contact Corporate Affairs Branch Services Division Telephone: 61 8 8226 5944 Facsimile: 61 8 8226 0914 . The Hon Mike Rann MP Premier of South Australia 200 Victoria Square ADELAIDE SA 5000 Dear Premier I am pleased to submit to you the Annual Report of the Department of the Premier and Cabinet for the year ended 30 June 2011. The Report has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Public Sector Act 2009, the Act’s accompanying regulations, the financial reporting requirements of the Public Finance and Audit Act 1987 and DPC Circular PC013 ‐ Annual Reporting Requirements. It demonstrates the scope of activities undertaken by the Department in meeting our targets for all departmental programs including the South Australia’s Strategic Plan targets for which we have lead agency responsibility. It also provides evidence of our performance in key areas, financial accountabilities and resource management. Yours sincerely Jim Hallion Chief Executive / /2011 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Chief Executive’s Review................................................................................................................... 4 Our Department............................................................................................................................... -

Migration Action

MIGRATION ACTION LIBRARY BROTHERHOOD OF ST. LAMPFaIPF Vol XV, Number 3 67 BRUNSWICK STREET December, 1993 FITZROY VICTORIA 3 The media SHOOTING THE MESSENGER OR THE MESSAGE? NEW BOOKS FROM EMC's BOOKSHOP B600 Labour Market Experience, Education and Training of Young Immigrants In Australia: An Intergenerational Study By: Flatau, Paul & Hemmings, Philip. 1992. RRP: $8.95 B601 Making Something of Myself: Turkish-Australian Young People By: Inglis, C.; Elley, J. & Manderson, L. 1992. RRP: $ 1 4 .9 5 B602 Directory of Ethnic Community Organizations in Australia 1992 By: Office of Multicultural Affairs. 1992. RRP: $ 2 9 .9 5 B604 Inventory of Australian Health Data Collections Which Contain Information On Ethnicity By: van Ommeren, Marijke & Merton, Carolyn. 1992. RRP: $ 16.95 B606 Temporary Movements of People to and From Australia By: Sloan, Judity & Kennedy, Sean. 1992. RRP: $ 1 2 .9 5 B607 Discrimination Against Immigrant Workers In Australia By: Foster, L.; Marshall, A. & W illiam s, L.S. RRP: $ 19.95 B 6 1 3 Growing Up Italian In Australia: Eleven Young Women Talk About Their Childhoods By: Travaglia, Joanne; Price, Rita & Dell'Oso, Anna Maria et al. 1993. RRP: $ 1 6 .9 5 B614 New Land, Last Home: The Vietnamese Elderly and The Family Migration Program By: Thomas, Trang & Balnaves, Mark. 1993. RRP: $9.95 B615 From All Corners: S ix Migrant Stories By: Henderson, Anne. 1993. The author tells the stories of six women who came to settle in Australia. RRP: $ 1 7 .9 5 Purchases from the EMC Bookshop may be made by calling the EMC Librarian on (03) 416 0044 / MIGRATION ACTION Contents VOL XV NUMBER 3, DECEMBER 1993 Editorial ISSN: 031 1-3760 The media - shooting the messenger or the message?.... -

Brett Sheehy CONFESSIONS of a GATEKEEPER

Address To The Inaugural Currency House/ Australia Business Arts Foundation 2009 Arts And Public Life Breakfast 31 March At The Sofi tel, Melbourne On Collins Brett Sheehy CONFESSIONS OF A GATEKEEPER Hello and welcome everyone. I quickly want to thank Harold for introducing me today. Harold barely knew me when, in November 2001, he fl ew from Melbourne to Sydney to attend my fi rst ever festival launch in Customs House down at Sydney’s Circular Quay. His reason was simple - he loves the arts, I was a fairly new kid on the festival block, and he wanted to show his support. And that support has continues to this day, unabated. I appreciate it tremendously, and it’s a privilege to fi nally share a stage with him, in what is now, mutually, our hometown. So thank you Harold. These confessions of an arts gatekeeper which I’m going to share this morning are personal, frequently intuitive, born of 25 years of observation and experience in the arts, but also not absolutes – all are debatable, but not one, I think, is disprovable. An arts gatekeeper is really a kind of artistic ‘door bitch’, someone charged with the responsibility of deciding when the ‘velvet rope’ is lifted, and which art will, and will not, be seen by the public of Australia. And while the metaphor of the ‘velvet rope’ makes light of it here, the role is actually riven with anxiety and stress – so important do I think the responsibility is, and so potentially charged with hubris. Gatekeepers come in many guises – festival directors, artistic directors of theatre and dance companies, museum and gallery curators, music directors of opera houses and orchestras, arts centre programmers, book publishers and record producers. -

Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir

Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Noël! Noël! Featuring the Brandenburg Choir Morgan Balfour (San Francisco) soprano 2019 Australian Brandenburg Orchestra Brandenburg Choir SYDNEY Matthew Manchester Conductor City Recital Hall Paul Dyer AO Artistic Director, Conductor Saturday 14 December 5:00PM Saturday 14 December 7:30PM PROGRAM Wednesday 18 December 5:00PM Mendelssohn Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Wednesday 18 December 7:30PM Anonymous Sonata à 9 Gjeilo Prelude MELBOURNE Eccard Ich steh an deiner Krippen hier Melbourne Recital Centre Crüger Im finstern Stall, o Wunder groβ Saturday 7 December 5:00PM Palestrina ‘Kyrie’ from Missa Gabriel Archangelus Saturday 7 December 7:30PM Arbeau Ding Dong! Merrily on High Handel ‘Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion’ NEWTOWN from Messiah, HWV 56 Friday 6 December 7:00PM Head The Little Road to Bethlehem Gjeilo The Ground PARRAMATTA Tuesday 10 December 7:30PM Vivaldi La Folia, RV 63 Handel Eternal source of light divine, HWV 74 MOSMAN Traditional Deck the Hall Wednesday 11 December 7:00PM Traditional The Coventry Carol WAHROONGA Traditional O Little Town of Bethlehem Thursday 12 December 7:00PM Traditional God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen Palmer A Sparkling Christmas WOOLLAHRA Adam O Holy Night Monday 16 December 7:00PM Gruber Stille Nacht Anonymous O Come, All Ye Faithful CHAIRMAN’S 11 Proudly supporting our guest artists. Concert duration is approximately 75 minutes without an interval. Please note concert duration is approximate only and subject to change. We kindly request that you switch off all electronic devices prior to the performance. This concert will be broadcast on ABC Classic on 21 December at 8:00PM NOËL! NOËL! 1 Biography From our Principal Partner: Macquarie Group Paul Dyer Imagination & Connection Paul Dyer is one of Australia’s leading specialists On behalf of Macquarie Group, it is my great pleasure to in period performance. -

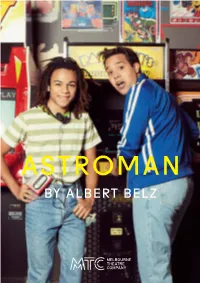

ASTROMAN by ALBERT BELZ Welcome

ASTROMAN BY ALBERT BELZ Welcome Over the course of this year our productions have taken you to London, New York, Norway, Malaysia and rural Western Australia. In Astroman we take you much closer to home – to suburban Geelong where it’s 1984. ASTROMAN In this touching and humorous love letter to the 80s, playwright Albert Belz wraps us in the highs and lows of growing up, the exhilaration of learning, and what it means to be truly courageous. BY ALBERT BELZ Directed by Sarah Goodes and Associate Director Tony Briggs, and performed by a cast of wonderful actors, some of them new to MTC, Astroman hits the bullseye of multigenerational appeal. If ever there was a show to introduce family and friends to theatre, and the joy of local stories on stage – this is it. At MTC we present the very best new works like Astroman alongside classics and international hits, from home and abroad, every year. As our audiences continue to grow – this year we reached a record number of subscribers – tickets are in high demand and many of our performances sell out. Subscriptions for our 2019 Season are now on sale and offer the best way to secure your seats and ensure you never miss out on that must-see show. To see what’s on stage next year and book your package visit mtc.com.au/2019. Thanks for joining us at the theatre. Enjoy Astroman. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the First Peoples of Country on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to all of Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. -

Koorie Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: January - February 2021

Koorie perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin: January - February 2021 This edition of the Koorie enrich your teaching program, see VAEAI’s Perspectives in Curriculum Bulletin Protocols for Koorie Education in Primary and features: Secondary Schools. For a summary of key Learning Areas and − Australia Day & The Great Debate Content Descriptions directly related to − The Aboriginal Tent Embassy Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories − The 1939 Cummeragunja Walk-off & and cultures within the Victorian Curriculum F- Dhungala – the Murray River 10, view or download the VCAA’s curriculum − Charles Perkins & the 1967 Freedom guide: Learning about Aboriginal and Torres Rides Strait Islander histories and cultures. − Anniversary of the National Apology − International Mother Language Day January − What’s on: Tune into the Arts Welcome to the first Koorie Perspectives in Australia Day, Survival Day and The Curriculum Bulletin for 2021. Focused on Great Debate Aboriginal Histories and Cultures, we aim to highlight Victorian Koorie voices, stories, A day off, a barbecue and fireworks? A achievements, leadership and connections, celebration of who we are as a nation? A day and suggest a range of activities and resources of mourning and invasion? A celebration of around key dates for starters. Of course any of survival? Australians hold many different views these topics can be taught at any time on what the 26th of January means to them. In throughout the school year and we encourage 2017 a number of councils controversially you to use these bulletins and VAEAI’s Koorie decided to no longer celebrate Australia Day Education Calendar for ongoing planning and on this day, and since then Change the Date ideas. -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

New Breed 2019 August 2019

Media Release For immediate release Sydney Dance Company and Carriageworks, in conjunction with The Balnaves New Breed 2019 Foundation, announce four Australian choreographers commissioned to create works for the acclaimed New Breed initiative that supports Australia’s next generation of choreographers. Meet the new breed of ‘★★★★ Full of a wonderful sense of adventure, but also with the choreographic and Australian dance theatrical nous to pull off an eclectic and consistently satisfying night of dance.’ – TimeOut creators Co-presented by Carriageworks and Sydney Dance Company – with the generous support of The Balnaves Foundation, New Breed 2019 will provide Australian choreographers Josh Mu (Melbourne), Lauren Langlois (Melbourne), Ariella Casu (Sydney) and Davide Di 28 Nov – 7 Dec Giovanni (Sydney) with an invaluable opportunity to work with Australia’s leading Carriageworks, Sydney contemporary dance company on a newly commissioned dance piece. Showcasing a rich diversity of choreographic ideas, this talented group of emerging choreographers will create brand new pieces on members of Sydney Dance Company. These four new works will comprise the New Breed 2019 season from 28 November to 7 December. The New Breed initiative made its debut in November 2014, supporting five emerging Australian choreographers through the commissioning and presentation of new dance work. Four sold out seasons in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018 ensued. The sixth instalment in the New Breed initiative will see Carriageworks, Sydney Dance Company and The Balnaves Foundation continue their commitment to the future of Australian contemporary dance, by supporting independent choreographers Josh Mu, Lauren Langlois, Ariella Casu and Davide Di Giovanni. From August, these dance makers will benefit from the extensive support of all the departments of Sydney Dance Company in readiness for their premiere season at Carriageworks, later this year. -

Florian Zeller Christopher Hampton

THE TRUTH BY Florian Zeller TRANSLATED BY Christopher Hampton DIRECTED BY Sarah Giles Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the First Peoples of Country on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand. We pay our respects to all of Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. WELCOME Florian Zeller is a name familiar to MTC audiences after our 2017 co-production of his play, The Father. Since then his star has been continuously on the rise and saw the film adaption of that play take home this year’s Academy Awards for Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actor. Another of his plays is currently receiving a film adaptation as well. Zeller is a towering talent and The Truth reinforces his deft skill of drawing audiences into layered stories which are never as straightforward as they appear. We are thrilled to be producing this play in its English translation by Zeller’s long-time collaborator and co-Academy Award-winner, Christopher Hampton. In The Truth, comedy shines through the underlying bed of deception and marital manipulations, and with a cast featuring the comic pedigree of Michala Banas, Stephen Curry, Bert LaBonté and Katrina Milosevic you really are set for an enjoyable night at the theatre. Directed by Sarah Giles, this production is the fourth Australian premiere in our 2021 program, and the second in our Act 2 suite of six productions. The Truth and other international works are beautifully complemented by an array of new Australian plays being presented in the months ahead. -

2008, WDA Global Summit

World Dance Alliance Global Summit 13 – 18 July 2008 Brisbane, Australia Australian Guidebook A4:Aust Guide book 3 5/6/08 17:00 Page 1 THE MARIINSKY BALLET AND HARLEQUIN DANCE FLOORS “From the Eighteenth century When we come to choosing a floor St. Petersburg and the Mariinsky for our dancers, we dare not Ballet have become synonymous compromise: we insist on with the highest standards in Harlequin Studio. Harlequin - classical ballet. Generations of our a dependable company which famous dancers have revealed the shares the high standards of the glory of Russian choreographic art Mariinsky.” to a delighted world. And this proud tradition continues into the Twenty-First century. Call us now for information & sample Harlequin Australasia Pty Ltd P.O.Box 1028, 36A Langston Place, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia Tel: +61 (02) 9869 4566 Fax: +61 (02) 9869 4547 Email: [email protected] THE WORLD DANCES ON HARLEQUIN FLOORS® SYDNEY LONDON LUXEMBOURG LOS ANGELES PHILADELPHIA FORT WORTH Ausdance Queensland and the World Dance Alliance Asia-Pacific in partnership with QUT Creative Industries, QPAC and Ausdance National and in association with the Brisbane Festival 2008 present World Dance Alliance Global Summit Dance Dialogues: Conversations across cultures, artforms and practices Brisbane 13 – 18 July 2008 A Message from the Minister On behalf of our Government I extend a warm Queensland welcome to all our local, national and international participants and guests gathered in Brisbane for the 2008 World Dance Alliance Global Summit. This is a seminal event on Queensland’s cultural calendar. Our Government acknowledges the value that dance, the most physical of the creative forms, plays in communicating humanity’s concerns.