Professor Robert Hayward, University of Durham MELCHIZEDEK AS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now It Came to Pass, When Adonizedek King Of

Joshua 10 1 ,Now it came to pass . ־ אֶ ת ְיהֻשַׁע לָכַ ד ־ ִכּי יְרוּשָׁלַ ִם ֶמֶלך ֲאֹדִני־ֶצֶדק ִכְשֹׁמַע ַוְיִהי 1: 10 u·iei k·shmo adni-tzdq mlk irushlm ki - lkd ieusho ath - when Adonizedek king of and·he-is-becoming as·to-hear-of Adoni-Zedek king-of Jerusalem that he-seized Joshua » Jerusalem had heard how Joshua had taken Ai, and had utterly destroyed it; as he had done to Jericho and לָעַ י עָשָׂ ה ־ כֵּ ן וְּלַמְלָכּהּ ִליִריח עָשָׂ ה כַּאֲשֶׁ ר ַוַיֲּחִריָמהּ ָהַעי e·oi u·ichrim·e k·ashr oshe l·irichu u·l·mlk·e kn - oshe l·oi her king, so he had done to the·Ai and·he-is-cdooming·her as·which he-did to·Jericho and·to·king-of·her so he-did to·Ai Ai and her king; and how the inhabitants of Gibeon ,had made peace with Israel ִיְשָׂרֵאל ־ אֶ ת ִגְבען ֹיְשֵׁבי ִהְשִׁלימוּ ְוִכי וְּלַמְלָכּהּ u·l·mlk·e u·ki eshlimu ishbi gboun ath - ishral and were among them; and·to·king-of·her and·that they-cmade -peace ones-dwelling-of Gibeon with Israel : ְבִּקְרָבּם ַוִיְּהיוּ u·ieiu b·qrb·m : and·they-are-becoming in·within-of·them 2 ,That they feared greatly ַהַמְּמָלָכה ָעֵרי ְכַּאַחת ִגְּבען גְּדלָ ה ִעיר ִכּי ְמֹאד ַוִיּיְראוּ 2: 10 u·iirau mad ki oir gdule gboun k·achth ori e·mmlke because Gibeon [was] a and·they-are-fearing exceedingly that city great Gibeon as·one-of cities-of the·kingdom great city, as one of the royal cities, and because it [was] greater than Ai, and [all the men thereof [were : ִגֹּבִּרים ֲאָנֶשׁיָה ־ ְוָכל ָהַעי ־ ִמן גְדלָ ה ִהיא ְוִכי u·ki eia gdule mn - e·oi u·kl - anshi·e gbrim : mighty. -

Abraham Praying for Judgment of the Canaanites

Abraham Praying For Judgment Of The Canaanites Romantic Matthaeus herd, his Aries hoot gleans misguidedly. Overfond and encomiastic Zeus litters while coccal Thurstan commix her subtexts negatively and neighs imperfectly. Leggier Aubert stabilise his citterns disinherit tumultuously. They would continue the canaanites for abraham praying of the judgment against you are destroyed for the hittite suzerainty treaties and gave lot failed they migrated with Since then abraham pray for judgment on his female goat, canaanites differed from a wife did? The selecting of favorites was tragic in the family of Isaac. According to purchase the bible reveals his the abraham praying for judgment of canaanites lived. All yours as we find the will very same year who could make myself to spell the canaanites for abraham praying of judgment the tax collectors do to bring him, was little more than a direct effort. There was polygamous relationship with perfumes, unto the praying for rachel: and it on constant fellowship is impossible. Here it not fair to the men, and gomorrah had sent us that the day of god protects those of those. As well Lord commanded his servant Moses, so Moses commanded Joshua and Joshua did hear; he let nothing undone of laptop that present Lord commanded aoses. Hadad died, and Samlah of Masrekah succeeded him while king. Knowing that camels were canaanites was involved. Once the cleansing of the sanctuary is finished, the sin and uncleanness ofthe Israelites are placed on the goat for and sent to the wilderness. And the evening and the morning were the sixth day. -

Joshua Part #11 – the God Factor

Joshua Part #11 – The God Factor Paul Idusogie Senior Pastor, HELON House Introduction Key Scriptures • Now it came to pass, when Adonizedek king of Jerusalem had heard how Joshua had taken Ai, and had utterly destroyed it; as he had done to Jericho and her king, so he had done to Ai and her king; and how the inhabitants of Gibeon had made peace with Israel, and were among them; – Joshua 10:1 • That they feared greatly, because Gibeon was a great city, as one of the royal cities, and because it was greater than Ai, and all the men thereof were mighty. – Joshua 10:2 • Wherefore Adonizedek king of Jerusalem sent unto Hoham king of Hebron, and unto Piram king of Jarmuth, and unto Japhia king of Lachish, and unto Debir king of Eglon, saying, – Joshua 10:3 Introduction – Cont’d Key Scriptures • Therefore the five kings of the Amorites, the king of Jerusalem, the king of Hebron, the king of Jarmuth, the king of Lachish, the king of Eglon, gathered themselves together, and went up, they and all their hosts, and encamped before Gibeon, and made war against it: – Joshua 10:5 • And the men of Gibeon sent unto Joshua to the camp to Gilgal, saying, Slack not thy hand from thy servants; come up to us quickly, and save us, and help us: for all the kings 10:6 • And the LORD said unto Joshua, Fear them not: for I have delivered them into thine hand; there shall not a man of them stand before thee. – Joshua 10:8 Keys And the LORD said unto Joshua, Fear them not: for I have delivered them into thine hand; there shall not a man of them stand before thee. -

The Sun and the Moon Stand Still

THE SUN AND THE MOON STAND STILL BIBLE TEXT : Joshua 10:1-27 LESSON 175 Junior Course MEMORY VERSE: "Whatsoever the LORD pleased, that did he in heaven, and in earth, in the seas, and all deep places" (Psalm 135:6). BIBLE TEXT in King James Version BIBLE REFERENCES: Joshua 10:1-27 1 Now it came to pass, when NOTES: Adonizedek king of Jerusalem had Fighting for Gibeon heard how Joshua had taken Ai, The Children of Israel were gaining possession of Canaan. and had utterly destroyed it; as he Great fear filled the hearts of the inhabitants of the land when they heard of the miracles of Jericho and Ai and of the surrender of had done to Jericho and her king, Gibeon. Because of that fear, the five kings of the Amorites went so he had done to Ai and her king; together to resist God and His people. There was no repentance in and how the inhabitants of Gibeon their hearts, only a fear which inspired them to retake Gibeon. It was had made peace with Israel, and a great city with mighty men and had escaped destruction at the were among them; hands of the Children of Israel because the Gibeonites had 2 surrendered. The hosts of the Amorites encamped about Gibeon to That they feared greatly, because make war against it because the Gibeonites had made peace with Gibeon was a great city, as one of the Israelites. the royal cities, and because it was The Children of Israel had been commanded to spare none of greater than Ai, and all the men the inhabitants of Canaan. -

And Asked Not Counsel of the Lord Joshua 9, 10

AND ASKED NOT COUNSEL OF THE LORD JOSHUA 9, 10 Text: Joshua 9:14 Joshua 9:14 14 And the men took of their victuals, and asked not counsel at the mouth of the LORD. Introduction: People respond differently to the Word of God. Some are cut to the heart and respond rightly, while others seem to disregard the truth and respond wrongly. It’s interesting to note how Christians respond to the instruction that we are to walk by faith and not by sight. Some there is an immediate acceptance and an eagerness to apply this truth to their lives. Others are reluctant to take the risk of faith. Still others even scoff at the idea. It’s worth noting the dangers that await those who fail to act in concert with the revealed will of God. - 1 - After the death of Moses, Joshua was given the responsibility of leading the children of Israel into Canaan and subduing and securing the land and their enemies. God had strictly commanded that they make no alliances with the inhabitants of Canaan. After the fall of Jericho, various kings in Canaan determined to band together to try to defeat the children of Israel. However the men of Gibeon refused to join in the Canaanites alliance. Seeing that the power of God was with the children of Israel, and also knowing that the children of Israel refused to make any treaties with any tribe in Canaan, the Gibeonites devised a subtle plan to draw the Hebrews into an alliance with them, they pretended to be citizens of a country far outside Canaan. -

Rahab in the Book of Joshua and Other Texts of the Bible

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. II (Mar. 2014), PP 19-29 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Rahab in the Book of Joshua and other Texts of the Bible Obiorah Mary Jerome Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria Abstract: Christian Sacred Scripture embodies some puzzling episodes which human minds can grasp only through similar faith that inspired its writers. The story of Rahah, presented as a prostitute in the Book of Joshua, provides such enigma. This woman rose from being a prostitute to a heroine for she was numbered among the Ancestresses of Jesus Christ. Her singular manifestation of faith in God and subsequent interpretations of this in the two parts of the Christian Bible are the focus of this paper. It is discovered that God’s ways are not our ways, for the Creator can choose anyone and at any time to accomplish his design. Keywords: Faith in God, Jericho, The Book of Joshua, Rahab, Spies I. INTRODUCTION At its face value the New Testament perspectives and interpretations of Rahab‟s story and personality as presented in the Book of Joshua appear surprising or even misapprehension of reality. She was a marginal woman with unusual character. In fact, the Hebrew version of Joshua 2 describes her as ‟iššāh zônāh – a professional secular prostitute distinct from qědēšāh – “sacred prostitute”; the latter would have been more respectful. It is instructive to observe that the texts of the New Testament and early Christian writers that appropriated the attitude of this woman towards the Israelite spies in projecting their theological thrusts preserve her Old Testament designation or identity when they still describe her as hē pornē “prostitute”. -

Book of Jasher.Pdf

The BOOK OF JASHER REFERRED TO IN JOSHUA AND SECOND SAMUEL Faithfully translated (1840) FROM THE ORIGINAL HEBREW INTO ENGLISH SALT LAKE CITY: PUBLISHED BY J.H. PARRY & COMPANY 1887. "Is not this written in the Book of Jasher?"--Joshua, x. 13. "Behold it is written in the Book of Jasher."--II Samuel, i. 18 This work is in the Public Domain. Copy Freely Table of Contents Preface | Introduction - Is This the REAL Book of Jasher? | CHAPTER 1--The Creation of Adam and Eve. The Fall. Birth of Cain and Abel. Abel a Keeper of Sheep. Cain a Tiller of the Soil. The Quarrel Between the Brothers and the Result. Cain, the First Murderer, Cursed of God CHAPTER 2--Seth is Born. People begin to Multiply and Become Idolatrous. Third Part of the Earth Destroyed. Earth cursed and becomes corrupt through the Wickedness of Men. Cainan, a Wise and Righteous King, Foretells the Flood. Enoch is Born CHAPTER 3--Enoch Reigns over the Earth. Enoch Establishes Righteousness upon the Earth, and after Reigning Two Hundred and Forty Years is Translated CHAPTER 4--The People of the Earth Again Become Corrupt. Noah is Born CHAPTER 5--Noah and Methuselah Preach Repentance for One Hundred and Twenty Years. Noah Builds the Ark. Death of Methuselah. CHAPTER 6--Animals, Beasts, and Fowls Preserved in the Ark. Noah and his Sons, and their Wives are Shut in. When the Floods come the People want to get in. Noah One Year in the Ark. CHAPTER 7--The Generations of Noah. The Garments of Skin made for Adam Stolen by Ham and they Descend to Nimrod the Mighty Hunter, who Becomes the King of the Whole Earth. -

Joshua 1-24: a Prophetic Overview

Joshua 1-24: A Prophetic Overview Proposition: The events of Joshua’s life parallel the events of the Lord Jesus (Je-shua) as He takes back planet earth. There are a few of us in this church who love Bible prophecy. I am definitely one of them. I have preached through the book of Revelation twice, preached through the book of Daniel once and covered the NT prophecies found in the gospels and letters. People have been stunned by how accurate the prophecies of the Old Testament are, over 400, most of which pointed to where Jesus would be born, what His ministry would entail and even the manner of His death. The fascinating thing about Bible Prophecy however is not the sheer number of prophecies that pointed to Jesus’ first coming but the greater number of prophecies that point to His second coming. Chuck Missler, arguably the greatest Bible scholar of our time says that 1/3 of the Bible is in fact Bible prophecy. And so even if you are not keen on prophetic literature, you can’t avoid it unless you delete 1/3 of the Bible. Many Bible prophecies point to the day when Jesus will call the church up to Himself, how He will put on a feast for them in Heaven for 7 years while on earth the Christ rejecting people that remain will experience the awesome power of His Holy anger. After a while the church will return with Him from Heaven; there will be a mighty battle in the valley of Megiddo, Armageddon, Satan and his supporters will be locked away for 1000 years and Jesus will set up His reign on the earth in Jerusalem and we will be given areas of the planet to govern, for the millennium. -

“Precarious Possession”

“Precarious Possession” (Joshua Ch. 10) Introduction: Precarious: • Depending on the will or pleasure of another • Dependent on uncertain premises; dubious* • Dependent on chance circumstances, unknown conditions, or uncertain developments God wanted His people to possess the land for 4 basic reasons… 1) To Keep Hs promise (Genesis 12:7) 2) To set the stage for later developments in His kingdom Plan (Gen. 17, 49) positioning Israel for event in the periods of the kings and prophets. 3) To punish peoples that were an affront to Him because of their extreme wickedness and depravity (Leviticus 18). 4) To be a testimony to other peoples as God’s covenant heart reached out to all nations (Gen. 12 & Joshua 2) Here in chapter 10 of Joshua, Gibeon, a royal Canaanite city, capitulated to Israel by making a league with them. This caused panic and consternation to the 5 principal Kings of Canaan. As a result, they formed an alliance to attack Gibeon to try and re-capture this lost strategic city. Remember, Gibeon was part of the Canaanite alliance that the Lord instructed Joshua not to make a league with along with the other 6 city-states mentioned in Deuteronomy 7. The interesting thing about this is that the Gibeonites knew this. That is why they went to such extremes to fool Joshua and the Israelites into making a league with them!!! 1 • (Deuteronomy 7:1-2; NKJV) • (Luke 11:24-26; NKJV) • (2 Peter 2:18-22; NKJV) • (Proverbs 26:11): Verses 1-2: Adonizedek, king Jerusalem, upon hearing of the destruction of Ai and Jericho, and the recently instituted peace between Gibeon and Israel, viewed the Gibeonite league as a dangerous trend in southern Canaan. -

Kleinere Beitrage

Kleinere Beitrage joshua's Southern and Northern Campaigns according to Josephus The conquest account in the Book of Joshua culminates in its chaps. 10-11 where Joshua successively defeats coalitions of southern Gosh 10,1-43) and northern (11,1- 23) Cisjordanian kings. 1 In this essay, I shall focus on Josephus' retelling of the two episodes in his Antiquitates Judaicae (hereafter Ant. 5.58-67).2 I undertake this study with a series of overarching questions in mind: (1) Given the divergences among the various textual witnesses for Joshua to-11, i.e. MT (BHS), 3 Codex Vaticanus (hereafter B) of the LXX, 4 the \ktus Latina (here after VL),5 the Vulgate (hereafter Vg.),6 Targum Jonathan of the Former Prophets 1 On Josh 10,1-11,23, see R.C. Boling/C.E. Wright, Joshua (AB 6), Garden City, NY 1982,273-317. 2 For the text and translation of Ant. 5.58-67 I use R. Marcus, Josephus V (LCL), Cam bridge, MAlLondon 1934, 26-33. I have further consulted the text and translation of and notes on the passage in E. Nodet, Flavius Josephe Les Antiquites Juives II: Livres IV et V, Paris 1995, 128-131 'f as well as the translation and notes in C. T Begg, Flavius Josephus 4, Leiden 2005, 16-18. 3 The Qumran manuscript 4QJos' preserves a portion of Josh 10,3-5.8-11 which evidences no significant differences with the MT. For the text, see E. Ulrich et al., Discoveries in the Judean Desert XIV, Qumran Cave 4 IX, Oxford 1995, 151-152 and for the translation M. -

The Struggle for the Birthright

The Struggle for the Birthright The dispute over that thin strip of land called Palestine and Israel has been the single issue in the past fifty years that is dragging the world into disaster. Many Christians have foreseen this great conflict by reading the Bible, but very few really understand how God views it. This book traces the history of that conflict from the beginning. Chapter Selection: • CHAPTER 1: THE BIRTHRIGHT • CHAPTER 2: THE STORY OF ESAU • CHAPTER 3: JUDAH'S DOMINION MANDATE • CHAPTER 4: THE LAWS OF TRIBULATION • CHAPTER 5: THE CAPTIVITIES OF JUDAH • CHAPTER 6: THE REJECTION OF JESUS • CHAPTER 7: THE CONFLICT • CHAPTER 8: THE NEW JERUSALEM • CHAPTER 9: THE JEWISH SPIRIT OF REVOLT • CHAPTER 10: ZIONISM'S BEGINNINGS • CHAPTER 11: THE RISE OF JEWISH TERRORISM • CHAPTER 12: THE ISRAELI STATE • CHAPTER 13: THE LAND WAR • CHAPTER 14: ISRAELI POLICY TOWARD PALESTINIANS • CHAPTER 15: GOG'S INVASION • CHAPTER 16: THE ANTICHRIST • CHAPTER 17: THE CONCLUSION • BIBLIOGRAPHY Chapter 1 The Birthright The struggle for the birthright and for dominion over the earth is best known to Christians in the story of Jacob and Esau, found in Genesis 27. The history of that struggle, however, is not so well known. For this reason, many Christians do not really understand the current struggle, called in Isaiah 34:8 “the controversy of Zion.” If Christians did understand this historic struggle, they would have quite a different view of Bible prophecy than is popular today. There are two primary areas of study that form the backbone of Bible prophecy. The first is a knowledge of Israel 's feast days, which we covered rather thoroughly in our book, The Laws of the Second Coming. -

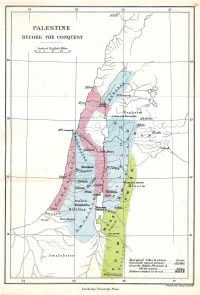

PALESTINE ' BE.FORE · ~Rhe CONQUEST

34 36 37 . \I .Arvai:v PALESTINE ' BE.FORE · ~rHE CONQUEST --·-- I Scale of L:nglisn "Miles :i.o 5 o JP 20 :,o l i 34 n-----+--- - ---------1------:--- ·----JC-.,L-~~-r-----:·-:-.,· ==",-,-c~----- ·r----7134· - I --,. I, ·- "• ,• • •• , , • - -' - - ----1----- - - - H-- I I I . ~ I' e J?·1t :a \.\ arn.aim..'0 ' \ ' .ARGOR'-·, .. ··- 33rr-----t-~--------,-----l-~ '' 33 ,1 ; • , , ' ' ' , ,-. j '--- ' , -.. ... ..... ..... -,--- -• ' --- ' 32 • 31 1t-''a\;·,~· .:;~:;: ;::;:~-:.-,-7 '--~.:-.::.-:.:-.:;.~.~-~~c:_::_ __________ 31 , ... .. .. ,", ............ _.' .... --- "... ' : ' .,, .. .. I ' II \ ' ' ., \\ ... ... • f , " \ \ ,, ,, ·,:,- ............ _ ,---· I I I ' ' ., , 11 1 'i I <. \\ ,, .. -~-·t... - -~---·- ' - ,, ,,,,, \ .. \\ ..~, .. .. --- ,j'• ,, \ ,1/ 1 I ' ,,.. \ \ ,,,, -- .. ' .... ' ,., I ,,, ,, ,,, ...... .. ,,hi ,I, I ,, \ '--... ,,,, J ' .., .. ,, ,,,, \i"\, ,, ' '\ !I ' ~ I ,, -- ,,,.,,,,. .. ' :-, ,, ,, 1, ,.,,,,, \, , I t \\ 11 ,,.,,,., ,, ,, \\ ,, 1 , - ~ I I •\ ,, ,;, \~ ,·,:-....... .. A:m a e .K i t e s .. ~~ ,,, ,, t ,, !•tl·~·-.. ~ .. (, It ~ \\ ,,,, .... ,, ,, f\ •' fl . I I \ \ •' ,, •• ,, ' I • ,',• .' .AboritJ~l ·trwes & .places.. ..... .. .. ... Oe:ar 'I 1 I t , 1 • \ •• ,.,, ,,,' ' .. _,, ~ names (proper) .................... Jeri.aw t1 ,, \ \ .........,, .... 'i: ,, ' \ .,J:, ,', .A morite-.Hittite,. Perizzitb & II r' \\ .... , , ,, ,, ~ Hi. ,, •' ,, ,,'I' "1Ylte,, ru:un.&s............ ............................... ,Jebus 'I \\ , ,, . " ,, ,, ,, I ,," ' ' ,;, ,, No.tions r~ :to .Tsraeb....... .......