Editors' Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Site © 2000, Dustin Evermore. to Navigate This Site, Click the Section

A Fuzion Fantasy role playing game by Dustin Evermore This site © 2000, Dustin Evermore. To navigate this site, click the section you want from the left frame, then select the chapter from the right frame. http://www.actionstudios.com/dol/index.html [4/4/2001 9:35:38 AM] History Religion Druids Saxon Religion Life in Britain The Otherworld http://www.actionstudios.com/dol/settingframe.html [4/4/2001 9:35:40 AM] HISTORY The history of the lands of Dawn of Legends is quite similar to the history of these lands of our world. However, there are some rather critical differences. The following outlines these. Ancient Times In the centuries B.C.E. (Before Common Era), the Celtic peoples populated much of Europe. Although the ancient Celts varied in description, they had a reasonably similar culture. The religion of the Celts in particular helped to unify tradition. The ancient druidic faith held the sum of all the Celt people’s knowledge and laws. The ancient druids generally maintained a neutrality in politics and gained impartiality in as judges of important social matters among the Celtic peoples. It has been said that a druid could stop a battle between warring tribes in these ancient times simply by walking between the armies. None challenged the authority and power of the druids. Coming of the Romans Boudicea, A Bard’s Tale The Romans line every hill, The conquests of Julius Ceasar targeted the druids as the nerve center and unifying force of Spears bright and deadly still, Blood red with silver shields, the Gallic Celts. -

Supplemental Information 1: System Assumptions

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Lab on a Chip This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Supplemental Information 1: System Assumptions Starting from the mass transfer equation: ∂C 2 + υ ⋅ ∇C = D∇ C + R ∂t (a) Distance between the droplet and air channels, O(10‐4) m is much smaller than the distance between the droplet channel PDMS device boundary O(10‐2) m, so little € mass transfer is out of the device and most mass transfer is into the air channel. (b) Assume the oil provides no resistance as compared to the PDMS. (c) Assume psuedo‐steady state since the PDMS boundaries and concentration boundary conditions are fixed: ∂C = 0 ∂t (d) No convection € υ = 0 (e) No reaction € R = 0 (f) Since the oil provides little resistance to mass transfer, the end of the droplets can be assumes as a constant value with surface area equal to the height of the droplet, h, multiplied by the width of the droplet (g) The concentration out the top is a function of the distance between droplet and air channels and will related to mass transfer out the sides for fixed droplet/air separations. This mass transfer can be represented by multiplying by an effective area. Therefore the system is simplified to one dimension. ∂ 2C = 0 ∂x 2 BC1 C(x = 0) = Csat,PDMS € Csat,PDMS BC2 C(x = d) = Cair = HCair Csat,air € (Csat,PDMS − HCair ) C = Csat,PDMS − x d € dC C − HC J = −D = D ( sat,PDMS air ) dx d € € Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Lab on a Chip This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2011 Supplemental Information 2: Droplet Change This derivation and model is derived assuming an approximate rectangular block shaped droplet with constant fluxes (Jtop, Jend, Jside) out of each the top, the ends and the side of the drop (Atop, Aend, Aside) in Equation S1. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

The Duality of the Composer-Performer

The Duality of the Composer-Performer by Marek Pasieczny Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Supervisors: Prof. Stephen Goss ©Marek Pasieczny 2015 The duality of the composer-performer A portfolio of original compositions, with a supplementary dissertation ‘Interviews Project: Thirteen Composers on Writing for the Guitar’. Abstract The main focus of this submission is the composition portfolio which consists of four pieces, each composed several times over for different combinations of instruments. The purpose of this PhD composition portfolio is threefold. Firstly, it is to contribute to the expansion of the classical guitar repertoire. Secondly, it is to defy the limits imposed by the technical facilities of the physical instrument and bring novelty to its playability. Third and most importantly, it is to overcome the challenges of being a guitarist-composer. Due to a high degree of familiarity with the traditional guitar repertoire, and possessing intimate knowledge of the instrument, it is often difficult for me as a guitarist-composer to depart from habitual tendencies to compose truly innovative works for the instrument. I have thus created a compositional approach whereby I separated my role as a composer from my role as a guitarist in an attempt to overcome this challenge. I called it the ‘dual-role’ approach, comprising four key strategies that I devised which involves (1) borrowing ‘New Music’ practices to defy traditionalist guitar tendencies which are often conservative and insular; (2) adapting compositional materials to different instrumentations; and expanding on (3) the guitar technique as well as; (4) the guitar’s inventory of extended techniques. -

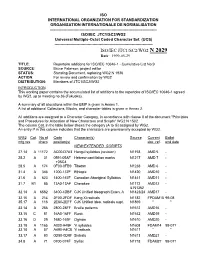

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29

ISO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N 2029 Date: 1999-05-29 TITLE: Repertoire additions for ISO/IEC 10646-1 - Cumulative List No.9 SOURCE: Bruce Paterson, project editor STATUS: Standing Document, replacing WG2 N 1936 ACTION: For review and confirmation by WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of JTC1/SC2/WG2 INTRODUCTION This working paper contains the accumulated list of additions to the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646-1 agreed by WG2, up to meeting no.36 (Fukuoka). A summary of all allocations within the BMP is given in Annex 1. A list of additional Collections, Blocks, and character tables is given in Annex 2. All additions are assigned to a Character Category, in accordance with clause II of the document "Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts" WG2 N 1502. The column Cat. in the table below shows the category (A to G) assigned by WG2. An entry P in this column indicates that the characters are provisionally accepted by WG2. WG2 Cat. No of Code Character(s) Source Current Ballot mtg.res chars position(s) doc. ref. end date NEW/EXTENDED SCRIPTS 27.14 A 11172 AC00-D7A3 Hangul syllables (revision) N1158 AMD 5 - 28.2 A 31 0591-05AF Hebrew cantillation marks N1217 AMD 7 - +05C4 28.5 A 174 0F00-0FB9 Tibetan N1238 AMD 6 - 31.4 A 346 1200-137F Ethiopic N1420 AMD10 - 31.6 A 623 1400-167F Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics N1441 AMD11 - 31.7 B1 85 13A0-13AF Cherokee N1172 AMD12 - & N1362 32.14 A 6582 3400-4DBF CJK Unified Ideograph Exten. -

13 Reflections on Tolkien's Use of Beowulf

13 Reflections on Tolkien’s Use of Beowulf Arne Zettersten University of Copenhagen Beowulf, the famous Anglo-Saxon heroic poem, and The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Author of the Century”, 1 have been thor- oughly analysed and compared by a variety of scholars.2 It seems most appropriate to discuss similar aspects of The Lord of the Rings in a Festschrift presented to Nils-Lennart Johannesson with a view to his own commentaries on the language of Tolkien’s fiction. The immediate pur- pose of this article is not to present a problem-solving essay but instead to explain how close I was to Tolkien’s own research and his activities in Oxford during the last thirteen years of his life. As the article unfolds, we realise more and more that Beowulf meant a great deal to Tolkien, cul- minating in Christopher Tolkien’s unexpected edition of the translation of Beowulf, completed by J.R.R. Tolkien as early as 1926. Beowulf has always been respected in its position as the oldest Germanic heroic poem.3 I myself accept the conclusion that the poem came into existence around 720–730 A.D. in spite of the fact that there is still considerable debate over the dating. The only preserved copy (British Library MS. Cotton Vitellius A.15) was most probably com- pleted at the beginning of the eleventh century. 1 See Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, 2000. 2 See Shippey, T.A., The Road to Middle-earth, 1982, Pearce, Joseph, Tolkien. -

Of Elves and Men Simon J

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 1 2016 Fantasy Incarnate: Of Elves and Men Simon J. Cook Dr. None, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Esthetics Commons, Intellectual History Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Cook, Simon J. Dr. (2016) "Fantasy Incarnate: Of Elves and Men," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol3/iss1/1 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Services at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Cook: Fantasy Incarnate Fantasy Incarnate: Of Elves and Men Introduction The following essay arises out of sustained engagement with the section of J.R.R. Tolkien’s On Fairy Stories entitled ‘Origins’. This section is dense, often elliptical, sometimes cryptic, with depths that have yet to be plumbed. It defies easy exegesis. My attempt to understand the ideas behind the text have led me far afield – into other sections of the essay, into other writings by Tolkien, and into works by other scholars which, in varying degrees, illuminate Tolkien’s thought. I have yet to exhaust this material and more remains to be said. What fruit I now present from my exegetical labour boils down to two claims: that loss of historical memory plays a vital role in Tolkien’s account of mythology, and that the notion of incarnation provides a key to his conception of fantasy.1 The essay consists of four main sections. -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

MUFI Character Recommendation V. 3.0: Alphabetical Order

MUFI character recommendation Characters in the official Unicode Standard and in the Private Use Area for Medieval texts written in the Latin alphabet ⁋ ※ ð ƿ ᵹ ᴆ ※ ¶ ※ Part 1: Alphabetical order ※ Version 3.0 (5 July 2009) ※ Compliant with the Unicode Standard version 5.1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ※ Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI) ※ www.mufi.info ISBN 978-82-8088-402-2 ※ Characters on shaded background belong to the Private Use Area. Please read the introduction p. 11 carefully before using any of these characters. MUFI character recommendation ※ Part 1: alphabetical order version 3.0 p. 2 / 165 Editor Odd Einar Haugen, University of Bergen, Norway. Background Version 1.0 of the MUFI recommendation was published electronically and in hard copy on 8 December 2003. It was the result of an almost two-year-long electronic discussion within the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (http://www.mufi.info), which was established in July 2001 at the International Medi- eval Congress in Leeds. Version 1.0 contained a total of 828 characters, of which 473 characters were selected from various charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 355 were located in the Private Use Area. Version 1.0 of the recommendation is compliant with the Unicode Standard version 4.0. Version 2.0 is a major update, published electronically on 22 December 2006. It contains a few corrections of misprints in version 1.0 and 516 additional char- acters (of which 123 are from charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 393 are additions to the Private Use Area). -

Tolkien's Lost Knights

Volume 39 Number 1 Article 9 Fall 10-15-2020 Tolkien's Lost Knights Ben Reinhard Christendom College Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Reinhard, Ben (2020) "Tolkien's Lost Knights," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 39 : No. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol39/iss1/9 OLKIEN ’S L OST KNIGHTS BEN REINHARD OLKIEN IS OFTEN CONSIDERED A STOLIDLY TRADITIONAL and even reactionary T author, and for good reason. Tolkien himself seemed almost to welcome the labels, and his debt to traditional models is obvious to all. -

Summer's Crossing

Summer’s Crossing The Iron Fey Julie Kagawa A Midsummer's Nightmare? Robin Goodfellow. Puck. Summer Court prankster, King Oberon's right hand, bane of many a faery queen's existence—and secret friend to Prince Ash of the Winter Court. Until one girl's death came between them, and another girl stole both their hearts. Now Ash has granted one favor too many and someone's come to collect, forcing the prince to a place he cannot go without Puck's help—into the heart of the Summer Court. And Puck faces the ultimate choice—betray Ash and possibly win the girl they both love, or help his former friend turned bitter enemy pull off a deception that no true faery prankster could possibly resist. An ebook exclusive novella from Julie Kagawa's Iron Fey series. Chapter One And as I am an Honest Puck Names. What’s in a name, really? I mean, besides a bunch of letters or sounds strung together to make a word. Does a rose by any other name really smell as sweet? Would the most famous love story in the world be as poignant if it was called Romeo and Gertrude? Why is what we call ourselves so important? Heh, sorry, I don’t usually get philosophical. I’ve just been wondering lately. Names are, of course, very important to my kind. Me, I have so many, I can’t even remember them all. None of them are my True Name, of course. No one has ever spoken my real name out loud, not once, despite all the titles and nicknames and myths I’ve collected for myself over the years. -

2017 MFA MSA Finalists Press Release

The Mythopoeic Society PRESS RELEASE: June 5, 2017 2017 Mythopoeic Award Finalists Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature Hairston, Andrea. Will Do Magic For Small Change (Aqueduct Press, 2016). Kowal, Mary Robinette. Ghost Talkers (Tor, 2016). McKillip, Patricia A. Kingfisher (Ace, 2016). Stiefvater, Maggie, The Raven Cycle: The Raven Boys (Scholastic, 2012); The Dream Thieves (Scholastic, 2013); Blue Lily, Lily Blue (Scholastic, 2014); and The Raven King (Scholastic, 2016). Walton, Jo. Thessaly Trilogy: The Just City (Tor, 2015); The Philosopher Kings (Tor, 2015); Necessity (Tor, 2016). Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Children’s Literature Gidwitz, Adam. The Inquisitor’s Tale: Or, The Three Magical Children and their Holy Dog (Dutton, 2016). Grove, S. E. The Mapmakers Trilogy: The Class Sentence (Viking 2014); The Golden Specific (Viking, 2015); The Crimson Skew (Viking, 2015). Hodder, Bridget. The Rat Prince (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2016). Lin, Grace. When the Sea Turned to Silver (Little, Brown, 2016). Sherman, Delia. The Evil Wizard Smallbone (Candlewick, 2016). Mythopoeic Scholarship Award in Inklings Studies Coutras, Lisa. Tolkien’s Theology of Beauty: Majesty, Splendor, and Transcendence in Middle Earth (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016). Higgins, Sørina, ed. The Chapel of the Thorn by Charles Williams (Apocryphile Press, 2015). Donovan, Leslie, ed. Approaches to Teaching Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and Other Works (Modern Language Association, 2015). Tolkien, Christopher, ed. Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell by J.R.R. Tolkien (Houghton Mifflin, 2014). Zaleski, Philip and Carol Zaleski, The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015).