UNIVERSITY of CALGARY the Construction of Intimate Partner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drayton Valley, Alberta, T7a 1R1 Phone: (780) 542-7777 Edm

JP pi m MUNICIPAL DISTRICT I OF BRAZEAU NO. 77 REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING October 11, 2001 p pi p pi MUNICIPAL DISTRICT OF BRAZEAU NO. 77 REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA DATE: 2000 10 11 TIME: 9:00 AM PLACE: M.D. ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, P COUNCIL CHAMBERS Page Nos. Call to Order » Present 1. Addition to and Adoption of the Agenda 2. Adoption of the Minutesof the Council Meeting of 2001 09 26. 3. Business Arising 4. Emergent Items 5. Delegations/Appointments p, 11:00 Ratepayer Concerns 6. Finance Matters a) Cash Statement and Investment Summary 1-2 - reports attached p) 7. Planning, Development & Land Matters a) Application for Amendment (text) to Land Use Bylaw 368-99 - Proposed Bylaw 410-2001 Blk. 6, Plan 772 2959 Pt.ofNW33-49-07-W5 Owner: Mr. Bob Dow 3-15 - report attached 8. General Matters a) Policy on Use of Undeveloped Road Allowances for Access Routes 16-24 - reports attached as per Council Motion 508-01 b) Ratification of Letter of Support for the Omniplex 25-26 - correspondence attached c) Renovations to Wishing Well Apartments 27-28 - correspondence attached r COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA -2- 200110 11 d) Bylaw No. 409-2001 - to adopt a modified voting procedure 29-31 - bylaw and ministerialorder attached e) Passing of County of St. Paul CAO 32 - copy of correspondence from the AAMD&C attached f) Resolution from County of Camrose in regards to LiabilityProtection for Municipal Officers 33-35 - report and recommendation attached g) Agenda Items for Reeves' Meeting 36 - correspondence attached h) Water and Sewer Agreement 37-43 I - report and recommendation attached p 9. -

The Calgary Congress

AN AGENDA FOR A REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF THE TOWN OF INNISFAIL SCHEDULED FOR MONDAY, JUNE 12,2006 COMMENCING AT 7:00P.M. IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS. IN ATTENDANCE: MAYOR KEN GRAHAM COUNCILORS PATT CHURCHILL, DON SHYGERA, TRACEY WALKER, DEREK BAIRD, GARY MACDONALD, JASON HEISTAD C.A.O. DALE MATHER C.F.O. BARBARA SCOTT DIR. OF OPER. TIM AINSCOUGH DEV. OFFICER ELWIN WIENS ABSENT: ADOPT AGENDA: ______________________ AND -=~~~~~~~~~~~~ THAT THE AGENDA FOR THE REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL SCHEDULED FOR MONDAY, JUNE 12, 2006 BE ADOPTED AS PRESENTED I AMENDED. CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY ADOPT MINUTES: ------~--~~~-=~~ AND ----------------------~-- THAT THE MINUTES OF THE PREVI OUS REGULAR MEETING HELD ON TUESDAY, MAY 23, 2006 BE ADOPTED AS PRESENTED I AMENDED. CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY TlfE MINUTES 01!' A REGULAR MEETING OF THE COUNCIL Oli' THE TOWN OF JNNJSFAIL fiELD ON TUESDAY, MAY23, 2006 COMMENCING AT 7:00P.M. IN THE TOWN OFFICE. IN ATI'ENDANCE: MAYOR: KEN GRAHAM COUNCILORS: GARY MACDONALD, DEREK DAfRD, TRACEY WALKER, DON Sl:IYGERA, PArr CtrURCHILL, JASON HEJSTAD C.A.O.: DALE MATHER C.F.O.: DARBARASCOTT DTR. OF OPER: TIM AJNSCOUGIT DEY. Ol<'FICER: ELWfNWI:ENS INGHAM PRESENTATION: COUNCIL PRESENTED A PLAQUE TO GARTH INGHAM IN RECOGNITION OF 90 YEARS OF BUSINESS TN INNISFAIL. ADOPT AGENDA: BAIRD & SHYGERA- THAT THE AGENDA FOU THE REGULAR MEETJNG SCIJEI>ULED FOR TUESDAY MAY 23, 2006 BE ADOPTED AS J>RESENTED. CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY ADOPT MINUTES: CHlJRCRILL & MACDONALD- THAT THE MlNUTES OF TBE PREVIOUS MEETING HELD ON MONDAY, MAY 8, 2006 BE ADOPTED AS PRESENTED. CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY OATH OJ? OFFICE - THE OATH OF OFI~ICE OF DEJ>UTY MAYOR WAS DEI'UTY MAYOR: I'RESCRffiED TO COUNCILOR PATT CHURCBJLL FOR TilE ENSUING TEIREE MONTH PElUOD. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 144 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ....................................154 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.......................................152 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar........................................153 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer...................................154 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston....................................156 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ..............................157 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ....................................154 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong................................153 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ............................155 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .......................................154 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson..............................156 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Alberta Hansard Thursday, November 24, 2011 Issue 40a The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fourth Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Zwozdesky, Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Hon. Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL), Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Official Opposition Whip Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (W), Knight, Hon. Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Wildrose Opposition House Leader Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Berger, Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Deputy Government House Leader Blackett, Hon. Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Official Opposition House Leader Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (W) Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) Leader of the ND Opposition Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), McQueen, Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Government Whip Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat (PC) Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL) Morton, F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Dallas, Hon. -

Proposed Severance Packages for Alberta Mlas

Proposed severance packages for Alberta MLAs If the Alberta government approves the recommendations of the all-party Member Services Committee, MLAs who retire or are defeated in 2005 would receive severance packages as per the following list. If the recommendations are approved, MLAs will receive three months’ pay for every year of service after March of 1989, based on the average of the three highest-paid years. Premier Ralph Klein $529,680 Opposition Leader Ken Nicol $356,112 ND Leader Raj Pannu $136,656 Speaker Ken Kowalski $474,816 Cabinet Ministers first elected in 1989 $474,816 Shirley McClellan Deputy Premier and Minister of Agriculture Pat Nelson Finance Halvar Jonson International and Intergovernmental Relations Ty Lund Infrastructure Stan Woloshyn Seniors Mike Cardinal Sustainable Resource Development Pearl Calahasen Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Cabinet Ministers first elected in 1993 $356,112 Gary Mar Health and Wellness Murray Smith Energy Ed Stelmach Transportation Clint Dunford Human Resources and Employment Lyle Oberg Learning Lorne Taylor Environment Gene Zwozdesky Community Development Victor Doerksen Innovation and Science Heather Forsyth Solicitor General Cabinet Ministers first elected in 1997 $237,408 Iris Evans Children’s Services David Hancock Justice and Attorney General Ron Stevens Gaming Greg Melchin Revenue Guy Boutilier Municipal Affairs David Coutts Government Services Cabinet Ministers first elected in 2001 $118,704 Mark Norris Economic Development Total severance pay for all 24 cabinet members: -

The Alberta Gazette

The Alberta Gazette Part I Vol. 100 Edmonton, Friday, December 31, 2004 No. 24 APPOINTMENTS (Provincial Court Act) Provincial Court Judge Appointed December 6, 2004 Dalton, Danielle Alice Marie Dunnigan, Gerald Sean, Q.C. Fisher, Frederick Charles, Q.C. Graham, Marlene Louise, Q.C. McLellan, Lillian Katherine Millar, Bruce Alexander, Q.C. RESIGNATIONS AND RETIREMENTS (Justice of the Peace Act) Resignation of Justice of the Peace December 2, 2004 Henderickson, Madeline Krieger, Brenda McHale, Donna McLaughlin, James Whitney, Rena THE ALBERTA GAZETTE, PART I, DECEMBER 31, 2004 GOVERNMENT NOTICES Energy Declaration of Withdrawal From Unit Agreement (Petroleum and Natural Gas Tenure Regulations) The Minister of Energy on behalf of the Crown in Right of Alberta hereby declares and states that the Crown in right of Alberta has withdrawn as a party to the agreement entitled “Long Coulee Sunburst “I” Unit No.1” effective December 1, 2004. Brenda Ponde, for Minister of Energy ______________ Production Allocation Unit Agreement (Mines and Minerals Act) Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 102 of the Mines and Minerals Act, that the Minister of Energy on behalf of the Crown has executed counterparts of the agreement entitled “Production Allocation Unit Agreement – Waterton Rundle Agreement #2) and that the Unit became effective on June 1, 2003. - 3634 - THE ALBERTA GAZETTE, PART I, DECEMBER 31, 2004 EXHIBIT “A” Attached to and made part of an Agreement Entitled “Production Allocation Unit Agreement for the Waterton 59 Well, Waterton Rundle -

Town of Drumheller COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES May 1, 2006 4:30 PM Council Chambers, Town Hall 703 - 2Nd Ave

Town of Drumheller COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES May 1, 2006 4:30 PM Council Chambers, Town Hall 703 - 2nd Ave. West, Drumheller, Alberta PRESENT: MAYOR: Paul Ainscough COUNCIL: Karen Bertamini Don Cunningham Larry Davidson Karen MacKinnon Sharel Shoff John Sparling CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER/ENGINEER: Ray Romanetz DIRECTOR OF INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES: Wes Yeoman DIRECTOR OF CORPORATE SERVICES: Michael Minchin DIRECTOR OF COMMUNITY SERVICES: Scott Blevins RECORDING SECRETARY: Corinne Macdonald 1.0 CALL TO ORDER Councillor Karen MacKinnon was sworn in as Deputy Mayor for the months of May and June, 2006. 2.0 MAYOR AINCOUGH’S OPENING REMARKS 2.1 Mayor P. Ainscough proclaimed May 13th to 20th as Alberta Crime Prevention Week. 2.2 Mayor P. Ainscough proclaimed May 14th to 20th as Census Week. Statistics Canada will conduct the Census of Population and Agriculture on May 16, 2006. Council Meeting May 1, 2006 Page 2 2.3 Mayor P. Ainscough proclaimed Wednesday as requested by the Communities in Bloom “Weed’ N Wednesdays. The group encouraged everyone to assist in making Drumheller the envy of every town for miles around. 2.4 Mayor P. Ainscough presented a letter from Minister Rob Renner of Municipal Affairs advising approval of the Town’s grant application under the 2005/06 Emergency Management Training Special Initiative. He advised that the Town had been awarded a grant of $2,500 in support of emergency management training. 2.5 Mayor P. Ainscough presented a letter from Minister Rob Renner of Municipal Affairs advising he recently authorized payment of a 2006/2007 Unconditional Municipal Grant to Municipalities and Metis Settlements. -

Report of the Standing Committee on Government Services

Standing Committee on Twenty-Sixth Legislature Third Session StandingGovernment Committee Services on NOVEMBER 2007 Government Services Report on Bill 2: Conflicts of Interest Amendment Act, 2007 COMMITTEES OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Standing Committee on Government Services 801 Legislature Annex Edmonton, AB T5K 1E4 (780) 644-8621 [email protected] November, 2007 To the Honourable Ken Kowalski Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Alberta The Standing Committee on Government Services has the honour to submit its Report containing recommendations on Bill 2, Conflicts of Interest Amendment Act, 2007 for consideration by the Legislative Assembly of Alberta. Harvey Cenaiko, MLA Calgary Buffalo Chair Standing Committee on Government Services Mo Elsalhy, MLA Edmonton-McClung Deputy Chair Standing Committee on Government Services Contents Members of the Standing Committee on Government Services 1 1.0 Introduction 2 2.0 Order of Reference 2 3.0 Recommendations 3.1 Proposed Amendments to Bill 2 3 Appendix A: Explanatory Notes 4 Appendix B: List of Submitters 5 MEMBERS OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT SERVICES 26th Legislature, Third Session Harvey Cenaiko, MLA Chair Calgary-Buffalo (PC) Mo Elsalhy, MLA Deputy Chair Edmonton-McClung (L) Moe Amery, MLA Richard Marz, MLA Calgary-East (PC) Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Dr. Neil Brown, MLA Brian Mason, MLA Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (NDP) David Coutts, MLA Bridget A. Pastoor, MLA Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lethbridge-East (L) Alana DeLong, MLA George VanderBurg, MLA Calgary-Bow (PC) Whitecourt-Ste. Anne (PC) Heather Forsyth, MLA Calgary-Fish Creek (PC) Temporary Substitutions* For Brian Mason: For Heather Forsyth: Dr. -

Klein Names New Cabinet, Reorganizes Some Portfolios

November 24, 2004 Klein names new Cabinet, reorganizes some portfolios Creation of Advanced Education portfolio recognizes postsecondary as a priority Edmonton... New faces at the Cabinet table and new assignments for Cabinet veterans are the highlights of the new Cabinet team named by Premier Ralph Klein. "This Cabinet brings together experience and new perspectives, and I believe those who now sit at the Cabinet table are the best team to lead Alberta into its centennial year and beyond," said Klein. The new Cabinet make-up includes a new ministry and some changes to old portfolios. With the increased emphasis on post-secondary education in the government's 20-year strategic plan, the former ministry of Learning has been split into Education (for K-12 education) and Advanced Education (for postsecondary education). The old Finance and Revenue portfolios have been merged into a single Finance ministry. The previous Infrastructure and Transportation portfolios have been combined into one Infrastructure and Transportation ministry. The Seniors ministry has had responsibility for community supports added, including the Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped and Persons with Development Disabilities programs, and is therefore renamed Seniors and Community Supports. The newly created portfolio of Restructuring and Government Efficiency will include responsibility for the Alberta Corporate Service Centre (previously under Government Services) and the Corporate Chief Information Officer (formerly with Innovation and Science). The Restructuring and Government Efficiency Minister will also be responsible for developing ideas and policies to streamline the delivery of government services. "The new restructuring ministry will help government in focusing on its most-important job, which is providing programs and services to Albertans effectively and efficiently," Klein said. -

S:\CLERK\JOURNALS\Votes & Proceedings\20050302 Vp.Wpd

Legislative Assembly Province of Alberta No. 2 VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS First Session Twenty-Sixth Legislature Wednesday, March 2, 2005 The Speaker took the Chair at 3:00 p.m. Speaker’s Statement The Speaker offered a prayer and a moment of silence was observed in recognition of the Late, The Honourable Dr. Lois E. Hole, who passed away on January 6, 2005. While awaiting the arrival of His Honour the Honourable the Lieutenant Governor, the Royal Canadian Artillery Band played a brief musical interlude. His Honour the Honourable the Lieutenant Governor entered the Assembly and took his seat on the Throne. Speaker's Address to the Lieutenant Governor The Speaker said: May it please Your Honour, the Legislative Assembly have elected me as their Speaker, though I am but little able to fulfil the important duties thus assigned to me. 1 If in the performance of those duties I should at any time fall into error, I pray that the fault may be imputed to me and not the Assembly, whose servant I am, and who, through me, the better to enable them to discharge their duties to their Queen and Province, hereby claim all their undoubted rights and privileges, especially that they may have freedom of speech in their debates, access to your person at all seasonable times, and that their proceedings may receive from you the most favourable construction. Statement by the Provincial Secretary The Provincial Secretary, Hon. Mr. Stevens, then said: I am commanded by His Honour the Honourable the Lieutenant Governor to declare to you that he freely confides in the duty and attachment of this Assembly to Her Majesty's person and Government, and, not doubting that the proceedings will be conducted with wisdom, temperance, and prudence, he grants and upon all occasions will recognize and allow the Assembly's constitutional privileges. -

2001 Provincial General Election

Members Elected to the Twenty-fifth Legislative Assembly Province of Alberta Electoral Division Name Political Affiliation 01 Athabasca-Wabasca Mike Cardinal Progressive Conservative 02 Lesser Slave Lake Pearl Calahasen Progressive Conservative 03 Calgary-Bow Alana DeLong Progressive Conservative 04 Calgary-Buffalo Harvey Cenaiko Progressive Conservative 05 Calgary-Cross Yvonne Fritz Progressive Conservative 06 Calgary-Currie Jon Lord Progressive Conservative 07 Calgary-East Moe Amery Progressive Conservative 08 Calgary-Egmont Denis Herard Progressive Conservative 09 Calgary-Elbow Ralph Klein Progressive Conservative 10 Calgary-Fish Creek Heather Forsyth Progressive Conservative 11 Calgary-Foothills Pat Nelson Progressive Conservative 12 Calgary-Fort Wayne Cao Progressive Conservative 13 Calgary-Glenmore Ron Stevens Progressive Conservative 14 Calgary-Lougheed Marlene Graham Progressive Conservative 15 Calgary-McCall Shiraz Shariff Progressive Conservative 16 Calgary-Montrose Hung Pham Progressive Conservative 17 Calgary-Mountain View Mark Hlady Progressive Conservative 18 Calgary-North Hill Richard Magnus Progressive Conservative 19 Calgary-North West Greg Melchin Progressive Conservative 20 Calgary-Nose Creek Gary Mar Progressive Conservative 21 Calgary-Shaw Cindy Ady Progressive Conservative 22 Calgary-Varsity Murray Smith Progressive Conservative 23 Calgary-West Karen Kryczka Progressive Conservative 24 Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview Julius Yankowsky Progressive Conservative 25 Edmonton-Calder Brent Rathgeber Progressive Conservative -

Quality Transmission

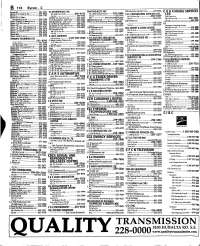

B 116 Byrom - C GDI Education 400 700 2 St SW 250-8686 Byrom M -283-4051 C3 ENTERPRISES INC CBM PROJEaS INC C G G CANADA SERVICES Byron B 224 Dtadel Pk NW - -547-4472 110- 6940 Rsher Rd SE 640-4191 335-10601 Southport Rd SW 270-3444 C D I PROFESSIONAL SERVICES LTD LTD Byron C- -269-3787 Fax Une 640-4192 F„une 225-2924 330- 736 8 Ave SW 266-1009 Data Processing Byron & Maru C21ETV 102- 351517 Ave SV/ 266-6150 Web: www.cbmprojects.com FaxUne 264-1961 500- 404 6 Ave SW 266-1011 205 Havenhurst Cr SW 212-7160 CBM Solutions Ltd 250-5582 C 2 C Marketing 7- 6143 4 St SE 255-1661 Fax Une 264-7054 Byron Frands 93 FaJworth Way N£ —293-2652 CBMC Christian Business Ministries Canada GDI Rentals Inc C2C Marketing 7-6143 4 St SE 255-1799 282-1599 Byron J lO- 2921 26 A»e SE 248-8374 C 2 C Mining corporation 264-5352 254-5286 CGI Byron JP 237-7592 C2 Energy Inc 425- 550 6 Ave SW 262-9226 fax Une 254-5297 FaxUne 282-5835 Information Technology Services Byron J P1201-1710 Radisson Dr SE —237-0141 C2 Paint 132817 Are SW 244-8931 CBN Woodwork Ltd CDL CARPET & FLOOR CENTRE 900- 800 5 Ave SW 218-8300 Byron.J P1201-1710 RatBsson DrSE —264-2479 Gil Petroleum Ltd 1-1935 27 Ave NE 291-9522 Fax Line 218-8309 ^n L 224 Otadel Pk NW 255-6914 400-33311 Ave SW 705-0537 7265 U StSE 255-1811 FaxUne 291-0827 Fax Une 255-0656 Insurance Business Services Byron L J — 276-2670 FaxUne 705-0538 CBS Construction 800- 7015 Macleod Trail SW 296*1308 Byron Neil 284-9364 CDL Syrtems 100- 3553 31 St NW —289-1733 Byron S 6520 23 Are nE 235-4770 C-WAY COURIERS 228 Riverstone PI SE 230-0794