The Sha'ar Hashamayim Yeshiva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rav Yisroel Abuchatzeira, Baba Sali Zt”L

Issue (# 14) A Tzaddik, or righteous person makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. (Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach; Sefer Bereishis 7:1) Parshas Bo Kedushas Ha'Levi'im THE TEFILLIN OF THE MASTER OF THE WORLD You shall say it is a pesach offering to Hashem, who passed over the houses of the children of Israel... (Shemos 12:27) The holy Berditchever asks the following question in Kedushas Levi: Why is it that we call the yom tov that the Torah designated as “Chag HaMatzos,” the Festival of Unleavened Bread, by the name Pesach? Where does the Torah indicate that we might call this yom tov by the name Pesach? Any time the Torah mentions this yom tov, it is called “Chag HaMatzos.” He answered by explaining that it is written elsewhere, “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li — I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine” (Shir HaShirim 6:3). This teaches that we relate the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and He in turn praises us. So, too, we don tefillin, which contain the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and HaKadosh Baruch Hu dons His “tefillin,” in which the praise of Klal Yisrael is written. This will help us understand what is written in the Tanna D’Vei Eliyahu [regarding the praises of Klal Yisrael]. The Midrash there says, “It is a mitzvah to speak the praises of Yisrael, and Hashem Yisbarach gets great nachas and pleasure from this praise.” It seems to me, says the Kedushas Levi, that for this reason it says that it is forbidden to break one’s concentration on one’s tefillin while wearing them, that it is a mitzvah for a man to continuously be occupied with the mitzvah of tefillin. -

Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World

EJIW Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World 5 volumes including index Executive Editor: Norman A. Stillman Th e goal of the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World is to cover an area of Jewish history, religion, and culture which until now has lacked its own cohesive/discreet reference work. Th e Encyclopedia aims to fi ll the gap in academic reference literature on the Jews of Muslims lands particularly in the late medieval, early modern and modern periods. Th e Encyclopedia is planned as a four-volume bound edition containing approximately 2,750 entries and 1.5 million words. Entries will be organized alphabetically by lemma title (headword) for general ease of access and cross-referenced where appropriate. Additionally the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World will contain a special edition of the Index Islamicus with a sole focus on the Jews of Muslim lands. An online edition will follow aft er the publication of the print edition. If you require further information, please send an e-mail to [email protected] EJIW_Preface.indd 1 2/26/2009 5:50:12 PM Australia established separate Sephardi institutions. In Sydney, the New South Wales Association of Sephardim (NAS), created in 1954, opened Despite the restrictive “whites-only” policy, Australia’s fi rst Sephardi synagogue in 1962, a Sephardi/Mizraḥi community has emerged with the aim of preserving Sephardi rituals in Australia through postwar immigration from and cultural identity. Despite ongoing con- Asia and the Middle East. Th e Sephardim have fl icts between religious and secular forces, organized themselves as separate congrega- other Sephardi congregations have been tions, but since they are a minority within the established: the Eastern Jewish Association predominantly Ashkenazi community, main- in 1960, Bet Yosef in 1992, and the Rambam taining a distinctive Sephardi identity may in 1993. -

Schools and Votes: Primary Education Provision and Electoral Support for the Shas Party in Israel

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 344 SO 034 268 AUTHOR Schiffman, Eitan TITLE Schools and Votes: Primary Education Provision and Electoral Support for the Shas Party in Israel. PUB DATE 2001-08-00 NOTE 27p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (San Francisco, CA, August 30- September 2, 2001). PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Research; Elementary Education; Foreign Countries; *Political Issues; *Political Parties; Religious Education IDENTIFIERS Empirical Research; Exploratory Studies; *Israel; Religious Fundamentalism; Research in Progress ABSTRACT This paper presents the foundation of an exploratory study about the effects of primary school education provision by the ultra-orthodox Shas party on electoral support for the party in Israel. Specifically, the research explores the question of whether and to what extent religious organizations that provide services for their clients are able to redirect the loyalties of their targeted communities away from the state and its ideology and toward the ideological goals of their organization. In addition to the discussion of prevailing theories for Shas's party success, the paper theorizes how the success of Shas can be regarded and tested as a case of political clientelism, manifested through the provision of services by the party's publicly funded education network, the Wellspring of Torah Education. Currently, the Shas school system operates schools (n=101) and kindergarten classrooms (n=484). The empirical research for this project is a work in progress. Therefore, no definitive conclusions are presented at this time, pending completion of field research in Israel. -

“For a Prayer in That Place Would Be Most Welcome”: Jews, Holy Shrines, and Miracles—A New Approach

“FOR A PRAYER IN THAT PLACE WOULD BE MOST WELCOME”: JEWS, HOLY SHRINES, AND MIRACLES—A NEW APPROACH ● by Ephraim Shoham-Steiner Recently, a small booklet entitled Gliding over the Lips of Sleepers, designed espe- cially for recital at the supposed burial site of the first century sage and head of the Sanhedrin, Rabbi Gamliel of Yavneh, was published in the modern Israeli town of Yavneh.1 In the introduction, author Eitan Zan’ani, a Jew of Yemenite descent, chose a quotation from Sefer Ha’midot (The Book of Merits, associated with the teachings of the late eighteenth-century Hassidic master Rabbi Nachman of Braslav) in praise of the visitation of such grave sites and the recital of prayers in loca sacra: “For by vis- iting these graves of the righteous and by prostrating oneself upon them, the Holy One, blessed be he, grants favors even if one is totally unworthy of them.” Turning to a “healing saint” in moments of distress is a longtime and cross-cultural phenomenon. Still in existence today, it was common practice among medieval European folk as part of a range of response methods used when a kinsman or neighbor fell ill or was found in a debilitating situation. In many cases vows were made by the ill person him- self, his immediate kin, or members of his close social circle to go on pilgrimage to the shrines of healing saints. Such visits were understood to be part of the healing process. Through close physical proximity to the saint, and by touching his or her rel- ics and artifacts, one could invoke the berakhah implicitly associated with such fig- ures, by assuming that a commitment was made to “convince” the saint to intervene on 1 This article is based on a chapter from my doctoral dissertation, “Social Attitudes Toward Marginal In- dividuals in Jewish Medieval European Society” (The Hebrew University Jerusalem 2002). -

Fine Judaica

t K ESTENBAUM FINE JUDAICA . & C PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS, GRAPHIC & CEREMONIAL ART OMPANY F INE J UDAICA : P RINTED B OOKS , M ANUSCRIPTS , G RAPHIC & C & EREMONIAL A RT • T HURSDAY , N OVEMBER 12 TH , 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY THURSDAY, NOV EMBER 12TH 2020 K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 115 Catalogue of FINE JUDAICA . Printed Books, Manuscripts, Graphic & Ceremonial Art Featuring Distinguished Chassidic & Rabbinic Autograph Letters ❧ Significant Americana from the Collection of a Gentleman, including Colonial-era Manuscripts ❧ To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 12th November, 2020 at 1:00 pm precisely This auction will be conducted only via online bidding through Bidspirit or Live Auctioneers, and by pre-arranged telephone or absentee bids. See our website to register (mandatory). Exhibition is by Appointment ONLY. This Sale may be referred to as: “Shinov” Sale Number Ninety-One . KESTENBAUM & COMPANY The Brooklyn Navy Yard Building 77, Suite 1108 141 Flushing Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11205 Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & C OMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Zushye L.J. Kestenbaum Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Judaica & Hebraica: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Shimon Steinmetz (consultant) Fine Musical Instruments (Specialist): David Bonsey Israel Office: Massye H. Kestenbaum ❧ Order of Sale Manuscripts: Lot 1-17 Autograph Letters: Lot 18 - 112 American-Judaica: Lot 113 - 143 Printed Books: Lot 144 - 194 Graphic Art: Lot 195-210 Ceremonial Objects: Lot 211 - End of Sale Front Cover Illustration: See Lot 96 Back Cover Illustration: See Lot 4 List of prices realized will be posted on our website following the sale www.kestenbaum.net — M ANUSCRIPTS — 1 (BIBLE). -

"El Misterio De La Creación Y El Árbol De La Vida En La Mística Judía: Una Interpretación Del Maasé Bereshit"

"EL MISTERIO DE LA CREACIÓN Y EL ÁRBOL DE LA VIDA EN LA MÍSTICA JUDÍA: UNA INTERPRETACIÓN DEL MAASÉ BERESHIT" Mario Javier Saban Dipòsit Legal: T.1423-2012 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, Ceremonial obJeCts & GraphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, nov ember 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 61 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, GR APHIC & CEREMONIAL A RT INCLUDING A SINGULAR COLLECTION OF EARLY PRINTED HEBREW BOOK S, BIBLICAL & R AbbINIC M ANUSCRIPTS (PART II) Sold by order of the Execution Office, District High Court, Tel Aviv ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th November, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th November - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 16th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Sempo” Sale Number Sixty Six Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky (Consultant) Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

Contentscontents SOME WORDS of ENCOURAGEMENT

CONTENTSContents SOME WORDS OF ENCOURAGEMENT .........................................3 IMPRESSIONS OF A JOURNEY ABROAD.......................................9 THE ROOT OF THE RIGHTEOUS WILL GIVE............................... 16 THE LATEST ACHIEVEMENTS OF OUR TEACHER AND RAV.. ....22 JTHE GAON AND TZADDIK RABBI YITZCHAK KADURI ZT”L....... 24 IS THERE WATER ABOVE THE FIRMAMENT? .............................29 THE NEED TO STUDY THE LAWS OF MODESTY ........................ 30 JERUSALEM HAS LOST A JEWEL ................................................34 THE LESSON OF SELF-SACRIFICE AND ITS IMPORTANCE FOR THE FUTURE.................................................................................36 THE HILLOULA OF RABBI HAIM PINTO ZT”L ............................... 40 A TZADDIK HAS LEFT THIS WORLD THE GAON RABBI NISSIM REBIBO ZATZAL............................................................................46 THE PASSING OF RABBI NATHAN BOKOBZA..............................48 THE DISASTER EFFECTS OF CARELESSNESS..........................49 THE ADMOR OF SATMAR HARAV MOSHE TEITELBAUM ZT”L....50 A FEW GOLDEN RULES................................................................52 DVOR TORAH IN HEBREW...........................................................54 UNDER AEGIS OF RABBI DAVID HANANIA PINTO CHLITA ISRAEL - ASHDOD The Pinto “OROT HAÏM OU MOSHE” REHOV HA-ADMOUR MI-BELZ 41/6 • ASHDOD • ISRAËL Associations around TEL: +972 88 856 125 • FAX: +972 88 563 851 ISRAEL - JERUSALEM the world, along with KOLLEL “OROTH HAIM OU MOSHE” KOLLEL “MISHKAN BETSALEL” Rabbi David Hanania Pinto YÉCHIVAT “NEFESH HAIM” REHOV BAYIT VAGAN 97 • JERUSALEM • ISRAEL Shlita, send you their best TEL: +972 26 433 605 • FAX: +972 26 433 570 U.S.A - CHEVRAT PINTO wishes for an exceptional new 8 MORRIS ROAD - SPRING VALLEY • NY 10977 • U.S.A TEL: 1 845 426 1276 • FAX: 1 845 426 1149 year 5767. Shana Tova! May PARIS - ORH HAÏM VÉMOSHÉ 11, RUE DU PLATEAU - 75019 PARIS • FRANCE we all be inscribed in the TEL: 01 42 08 25 40 - FAX: 01 42 08 50 85 LYON - HEVRAT PINTO Book of Life. -

Conversations

CONVERSATIONS Orthodoxy: Widening Perspectives Autumn 2020/5781 Issue 36 CONVERSATIONS CONTENTS In Honor of Rabbi Hayyim Angel, on His 25 Years of Rabbinic Service v RABBI MARC ANGEL Editor’s Introduction vii RABBI HAYYIM ANGEL How the Torah Broke with Ancient Political Thought 1 JOSHUA BERMAN Walking Humbly: A Brief Interpretive History of Micah 6:8 13 ERICA BROWN It’s in the Gene(alogy): Family, Storytelling, and Salvation 21 STUART HALPERN Hassidim and Academics Unite: The Significance of Aggadic Placement 30 YITZHAK BLAU Love the Ger: A Biblical Perspective 37 HAYYIM ANGEL Does the Gender Binary Still Exist in Halakha? 47 NECHAMA BARASH Four Spaces: Women’s Torah Study in American Modern Orthodoxy 68 RACHEL FRIEDMAN Three Short Essays 74 HAIM JACHTER The Yemima Method: An Israeli Psychological-Spiritual Approach 89 YAEL UNTERMAN You Shall Love Truth and Peace 103 DANIEL BOUSKILA Agnon’s Nobel Speech in Light of Psalm 137 108 JEFFREY SAKS Re-Empowering the American Synagogue: A Maslovian Perspective 118 EDWARD HOFFMAN Yearning for Shul: The Unique Status of Prayer in the Synagogue 125 NATHANIEL HELFGOT Halakha in Crisis Mode: Four Models of Adaptation 130 ARYEH KLAPPER Responsiveness as a Greatmaking Property 138 ANDREW ARKING Religious Communities and the Obligation for Inclusion 147 NATHAN WEISSLER SUBMISSION OF ARTICLES If you wish to submit an article to Conversations, please send the Senior Editor ([email protected]) or the Editor ([email protected]) a short description of the essay you plan to write. Articles should be written in a conversa- tional style and should be submitted typed, double spaced, as Word documents. -

AJS Perspectives: the Magazine TABLE of CONTENTS of the Association for Jewish Studies President Sara R

ERSPECTIVESERSPECTIVES AJSPPThe Magazine of the Association for Jewish Studies IN THIS ISSUE: Martyrdom through the Ages SPRING 2009 AJS Perspectives: The Magazine TABLE OF CONTENTS of the Association for Jewish Studies President Sara R. Horowitz From the Editor . 3 York University From the President . 4 Editor Allan Arkush From the Executive Director . 6 Binghamton University Editorial Board Martyrdom through the Ages Howard Adelman Introduction Queen's University Shmuel Shepkaru . 8 Alanna Cooper University of Massachusetts Amherst Foils or Heroes? On Martyrdom in First and Second Maccabees Jonathan Karp Daniel R. Schwartz . 10 Binghamton University Heidi Lerner Origins of Rabbinic Martyrology: Rabbi Akibah, the Song of Stanford University Songs, and Hekhalot Mysticism Frances Malino Joseph Dan . 14 Wellesley College Vanessa Ochs Radical Jewish Martyrdom University of Virginia Robert Chazan . 18 Riv-Ellen Prell Martyrs of 1096 “On Site” University of Minnesota Shmuel Shepkaru Eva Haverkamp . 22 University of Oklahoma What Does Martyrdom Lore Tell Us? Abe Socher Miriam Bodian . 26 Oberlin College Shelly Tenenbaum “The Final Battle” or “A Burnt Offering”?: Clark University Lamdan’s Masada Revisited Keith Weiser Yael S. Feldman . 30 York University Steven Zipperstein Perspectives on Technology Stanford University Scholarly Communication in the Twenty-first Century: Managing Editor A Changing Landscape Karin Kugel Executive Director Heidi Lerner . 36 Rona Sheramy Diarna: Digitally Mapping Mizrahi Heritage Graphic Designer Matt Biscotti Frances Malino and Jason Guberman-Pfeffer . 42 Wild 1 Graphics, Inc. Remembering Our Colleagues Please direct correspondence to: Joseph M. Baumgarten (1928 – 2008) Association for Jewish Studies Moshe Bernstein . 46 Center for Jewish History 15 West 16th Street Sarah Blacher Cohen (1936 – 2008) New York, NY 10011 Elaine Safer. -

Mikveh Israel Hashem

BS”D MIKVEH ISRAEL HASHEM JUST AS THE MIKVAH PURIFIES THE CONTAMINATED [TEMEIM], JUST THE SAME THE HOLY ONE BLESSED BE HE PURIFIES ISRAEL (MISHNA YOMA 8:9) MIKVEH ISRAEL HASHEM 1 THE BAAL SHEM TOV MERITED HIS LOFTY LEVELS THROUGH CONSTANT IMMERSIONS IN THE MIKVAH The Baal Shem Tov ZTK’L said that he merited great levels through constant immersions in the Mikvah, and they are much better than mortifications like fasting for this weakens the person and does not permit him to serve the Holy One Blessed be He. See then my friends how much can the Mikvah achieve Sefer Shaare Parnassah Tova, Tehillim Chapter 51 THE MIKVAH TODAY To our Jewish brothers, to those who listen and fear to the word of Hashem, and to those who strive to observe the Mitzvot of our Holy Torah It is known and revealed to everyone that the foundation of the holiness and the purity (Keddusha and the Tahara) of Israel depends on the Mikvah for purity, and due to our many sins in the latter times great are the pitfalls and dangers with the Mikvaot. And even though it will bring great anguish to those who fear the word of Hashem we must admit that the problems have emanated from the BATE DINIM for they have appointed supervising Rabbis, who don’t know and are not familiar with the laws of the Mikvahs. And in turn they knowingly and without knowing it cause the many to stumble in sin, and day after day they cause thousands of families to live in sin, and not any sin but a sin which warrants the punishment of KARET G-d save us. -

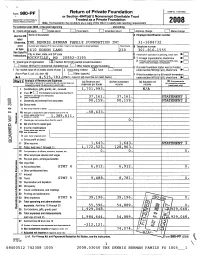

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF I

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I • or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements 2 00 8 For calendar year 2008 , or tax year beginning , and ending R ('hark au that annh, F__l Ind,sl return F__] 9:m2l rahirn I-1 e,nonnorl ratnrn 1 1 Adrlrocc nhanno hI,mn ,.h^nno Name of Use the IRS foundation A Employer identification number label Otherwise , HE DENNIS BERMAN FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 31-1684732 print Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number or type . 5410 EDSON LANE 220 301-816-1555 See Specific City or town, state , and ZIP code Instructions . C If exemption application is pending , check here OCKVILLE , MD 20852-319 5 D 1- Foreign organizations , check here ► 2. Foreignrganrzatac meetingthe85%test, H Check tYPtype oorganization 0X Section 501 (c)( 3 ) exempt Pprivate foundation check heere and atttach computation Section 4947(a )( 1 nonexempt charitable trust 0 Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foun dation status was termina ted I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method OX Cash Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part Il, col (c), line 16) = Other (specify ) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (Part I, column (d) must be on cash basis) ► $ 4 , 515 , 783 .