Popularity Number of Printings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina

The Evolution of the Roman Calendar Dwayne Meisner, University of Regina Abstract The Roman calendar was first developed as a lunar | 290 calendar, so it was difficult for the Romans to reconcile this with the natural solar year. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the calendar, creating a solar year of 365 days with leap years every four years. This article explains the process by which the Roman calendar evolved and argues that the reason February has 28 days is that Caesar did not want to interfere with religious festivals that occurred in February. Beginning as a lunar calendar, the Romans developed a lunisolar system that tried to reconcile lunar months with the solar year, with the unfortunate result that the calendar was often inaccurate by up to four months. Caesar fixed this by changing the lengths of most months, but made no change to February because of the tradition of intercalation, which the article explains, and because of festivals that were celebrated in February that were connected to the Roman New Year, which had originally been on March 1. Introduction The reason why February has 28 days in the modern calendar is that Caesar did not want to interfere with festivals that honored the dead, some of which were Past Imperfect 15 (2009) | © | ISSN 1711-053X | eISSN 1718-4487 connected to the position of the Roman New Year. In the earliest calendars of the Roman Republic, the year began on March 1, because the consuls, after whom the year was named, began their years in office on the Ides of March. -

Representing Roman Female Suicide. Phd Thesis

GUILT, REDEMPTION AND RECEPTION: REPRESENTING ROMAN FEMALE SUICIDE ELEANOR RUTH GLENDINNING, BA (Hons) MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis examines representations of Roman female suicide in a variety of genres and periods from the history and poetry of the Augustan age (especially Livy, Ovid, Horace, Propertius and Vergil), through the drama and history of the early Principate (particularly Seneca and Tacitus), to some of the Church fathers (Tertullian, Jerome and Augustine) and martyr acts of Late Antiquity. The thesis explores how the highly ambiguous and provocative act of female suicide was developed, adapted and reformulated in historical, poetic, dramatic and political narratives. The writers of antiquity continually appropriated this controversial motif in order to comment on and evoke debates about issues relating to the moral, social and political concerns of their day: the ethics of a voluntary death, attitudes towards female sexuality, the uses and abuses of power, and traditionally expected female behaviour. In different literary contexts, and in different periods of Roman history, writers and thinkers engaged in this same intellectual exercise by utilising the suicidal female figure in their works. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for providing the financial assistance necessary for me to carry out this research. The Roman Society also awarded a bursary that allowed me to undertake research at the Fondation Hardt pour I'etude de I'antiquite classique, in Geneva, Switzerland (June 2009). I am also grateful for the CAS Gender Histories bursary award which aided me while making revisions to the original thesis. -

Lesson Two--Rep To

Lesson Two: Rome’s Shift From a Republic to an Empire (Important Note: This lesson might work better being taught in 2 days. Review the lesson carefully before teaching. Perhaps the Republic to Caesar to Empire Reading and Word Wall could be made longer with a longer discussion and then the primary source and monument analyses can be accomplished the next day.) Lesson overview: Briefly remind students of yesterday’s lesson, emphasizing the process of reviewing each of Rome’s historical paradigms through analyzing primary sources and monuments and symbols. Once again review the essential question and remind students of the upcoming final assessment project. Then briefly overview the activities for today’s lesson. Students will then complete a KWL chart on the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. They will then read and report to each other on the “Rome to Caesar to Empire” reading in groups. After this, students will stay in groups and analyze the primary sources and monuments reflecting the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. Finally, the lesson will close with students completing a word wall using the “Rome to Caesar to Empire” reading and their primary source readings. This lesson satisfies the following Common Core and Career Readiness Standards for grades 6-12: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.3 Identify key steps in a text's description of a process related to history/ social studies (e.g., how a bill becomes law, how interest rates are raised or lowered). CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6 Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author's point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts). -

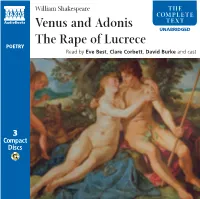

Venus and Adonis the Rape of Lucrece

NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 1 William Shakespeare THE COMPLETE Venus and Adonis TEXT The Rape of Lucrece UNABRIDGED POETRY Read by Eve Best, Clare Corbett, David Burke and cast 3 Compact Discs NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 2 CD 1 Venus and Adonis 1 Even as the sun with purple... 5:07 2 Upon this promise did he raise his chin... 5:19 3 By this the love-sick queen began to sweat... 5:00 4 But lo! from forth a copse that neighbours by... 4:56 5 He sees her coming, and begins to glow... 4:32 6 'I know not love,' quoth he, 'nor will know it...' 4:25 7 The night of sorrow now is turn'd to day... 4:13 8 Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey... 4:06 9 'Thou hadst been gone,' quoth she, 'sweet boy, ere this...' 5:15 10 'Lie quietly, and hear a little more...' 6:02 11 With this he breaketh from the sweet embrace... 3:25 12 This said, she hasteth to a myrtle grove... 5:27 13 Here overcome, as one full of despair... 4:39 14 As falcon to the lure, away she flies... 6:15 15 She looks upon his lips, and they are pale... 4:46 Total time on CD 1: 73:38 2 NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 3 CD 2 The Rape of Lucrece 1 From the besieged Ardea all in post.. -

Shakespeare's Rome

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15906-8 — Shakespeare Survey Edited by Peter Holland Excerpt More Information PAST THE SIZE OF DREAMING? SHAKESPEARE’SROME ROBERT S. MIOLA Ethereal Rumours citizens, its customs, laws and code of honour, its Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus enemies, wars, histories and myths. But (T. S. Eliot) Shakespeare knew Rome as a modern city of Italy as well, land of love, lust, revenge, intrigue and art, Confronting modernity, the speaker in setting or partial setting for eight plays. Portia dis- ‘ ’ The Wasteland recalled the ancient hero and guises herself as Balthazar, a ‘young doctor of ’ ‘ Shakespeare s play (his most assured artistic suc- Rome’ (Merchant, 4.1.152); Hermione’s statue is ’ cess , Eliot wrote elsewhere) as fragments of past said to be the creation of ‘that rare Italian master, grandeur momentarily shored against his present Giulio Romano’ (The Winter’s Tale, 5.2.96). And ruins. Contrarily, Ralph Fiennes revived Shakespeare knew both ancient and modern fi Coriolanus in his 2011 lm because he thought it Rome as the centre of Roman Catholicism, a modern political thriller: home of the papacy, locus of forbidden devotion For me it has an immediacy: I know that politician and prohibited practice, city of saints, heretics, getting out of that car. I know that combat guy. I’ve martyrs and miracles. The name ‘Romeo’, appro- seen him every day on the news and in the newspaper – priately, identifies a pilgrim to Rome. Margaret that man in that camouflage uniform running down the wishes the college of Cardinals would choose her street, through the smoke and the dust. -

Newsletter Nov 2011

imperi nuntivs The newsletter of Legion Ireland --- The Roman Military Society of Ireland In This Issue • New Group Logo • Festival of Saturnalia • Roman Festivals • The Emperors - AD69 - AD138 • Beautifying Your Hamata • Group Events and Projects • Roman Coins AD69 - AD81 • Roundup of 2011 Events November 2011 IMPERI NUNTIUS The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland November 2011 From the editor... Another month another newsletter! This month’s newsletter kind grew out of control so please bring a pillow as you’ll probably fall asleep while reading. Anyway I hope you enjoy this months eclectic mix of articles and info. Change Of Logo... We have changed our logo! Our previous logo was based on an eagle from the back of an Italian Mus- solini era coin. The new logo is based on the leaping boar image depicted on the antefix found at Chester. Two versions exist. The first is for a white back- ground and the second for black or a dark back- ground. For our logo we have framed the boar in a victory wreath with a purple ribbon. We tried various colour ribbons but purple worked out best - red made it look like a Christmas wreath! I have sent these logo’s to a garment manufacturer in the UK and should have prices back shortly for group jackets, sweat shirts and polo shirts. Roof antefix with leaping boar The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland. Page 2 Imperi Nuntius - Winter 2011 The newsletter of Legion Ireland - The Roman Military Society of Ireland. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Rape of Lucretia) Tears Harden Lust, Though Marble Wear with Raining./...Herpity-Pleading Eyes Are Sadly Fix’D/In the Remorseless Wrinkles of His Face

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Tarquin and Lucretia (Rape of Lucretia) Tears harden lust, though marble wear with raining./...Herpity-pleading eyes are sadly fix’d/In the remorseless wrinkles of his face... She conjures him by high almighty Jove/...Byheruntimely tears, her husband’s love,/By holy hu- man law, and common troth,/By heaven and earth and all the power of both,/That to his borrow’d bed he make retire,/And stoop to honor, not to foul desire.1(p17) UCRETIA WAS A LEGENDARY HEROINE OF ANCIENT shadow so his expression is concealed as he rips off Lucretia’s Rome, the quintessence of virtue, the beautiful wife remaining clothing. Lucretia physically resists his violence and of the nobleman Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus.2 brutality. A sculpture decorating the bed has fallen to the floor, In a lull in the war at Ardea in 509 BCE, the young the sheets are in disarray, and Lucretia’s necklace is broken, noblemen passed their idle time together at din- her pearls scattered. Both artists transmit emotion to the viewer, Lners and in drinking bouts. When the subject of their wives came Titian through her facial expression and Tintoretto in the vio- up, every man enthusiastically praised his own, and as their ri- lent corporeal chaos of the rape itself. valry grew, Collatinus proposed that they mount horses and see Lucretia survived the rape but committed suicide. After en- the disposition of the wives for themselves, believing that the best during the rape, she called her husband and her father to her test is what meets his eyes when a woman’s husband enters un- and asked them to seek revenge. -

The Triumph of Flora

Myths of Rome 01 repaged 23/9/04 1:53 PM Page 1 1 THE TRIUMPH OF FLORA 1.1 TIEPOLO IN CALIFORNIA Let’s begin in San Francisco, at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in Lincoln Park. Through the great colonnaded court, past the Corinthian columns of the porch, we enter the gallery and go straight ahead to the huge Rodin group in the central apse that dominates the visitor’s view. Now look left. Along a sight line passing through two minor rooms, a patch of colour glows on the far wall. We walk through the Sichel Glass and the Louis Quinze furniture to investigate. The scene is some grand neo-classical park, where an avenue flanked at the Colour plate 1 entrance by heraldic sphinxes leads to a distant fountain. To the right is a marble balustrade adorned by three statues, conspicuous against the cypresses behind: a muscular young faun or satyr, carrying a lamb on his shoulder; a mature goddess with a heavy figure, who looks across at him; and an upright water-nymph in a belted tunic, carrying two urns from which no water flows. They form the static background to a riotous scene of flesh and drapery, colour and movement. Two Amorini wrestle with a dove in mid-air; four others, airborne at a lower level, are pulling a golden chariot or wheeled throne, decorated on the back with a grinning mask of Pan. On it sits a young woman wearing nothing but her sandals; she has flowers in her hair, and a ribboned garland of flowers across her thighs. -

The Worship of Augustus Caesar

J THE WORSHIP OF AUGUSTUS C^SAR DERIVED FROM A STUDY OF COINS, MONUMENTS, CALENDARS, ^RAS AND ASTRONOMICAL AND ASTROLOGICAL CYCLES, THE WHOLE ESTABLISHING A NEW CHRONOLOGY AND SURVEY OF HISTORY AND RELIGION BY ALEXANDER DEL MAR \ NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY THE CAMBRIDGE ENCYCLOPEDIA CO. 62 Reade Street 1900 (All rights reserrecf) \ \ \ COPYRIGHT BY ALEX. DEL MAR 1899. THE WORSHIP OF AUGUSTUS CAESAR. CHAPTERS. PAGE. Prologue, Preface, ........ Vll. Bibliography, ....... xi. I. —The Cycle of the Eclipses, I — II. The Ancient Year of Ten Months, . 6 III. —The Ludi S^eculares and Olympiads, 17 IV. —Astrology of the Divine Year, 39 V. —The Jovian Cycle and Worship, 43 VI. —Various Years of the Incarnation, 51 VII.—^RAS, 62 — VIII. Cycles, ...... 237 IX. —Chronological Problems and Solutions, 281 X. —Manetho's False Chronology, 287 — XI. Forgeries in Stone, .... 295 — XII. The Roman Messiah, .... 302 Index, ........ 335 Corrigenda, ....... 347 PROLOGUE. THE ABYSS OF MISERY AND DEPRAVITY FROM WHICH CHRISTIANITY REDEEMED THE ROMAN EMPIRE CAN NEVER BE FULLY UNDERSTOOD WITHOUT A KNOWLEDGE OF THE IMPIOUS WoA^P OF EM- PERORS TO WHICH EUROPE ONCE BOWED ITS CREDULOUS AND TERRIFIED HEAD. WHEN THIS OMITTED CHAPTER IS RESTORED TO THE HISTORY OF ROME, CHRISTIANITY WILL SPRING A LIFE FOR INTO NEW AND MORE VIGOROUS ; THEN ONLY WILL IT BE PERCEIVED HOW DEEP AND INERADICABLY ITS ROOTS ARE PLANTED, HOW LOFTY ARE ITS BRANCHES AND HOW DEATH- LESS ARE ITS AIMS. PREFACE. collection of data contained in this work was originally in- " THEtended as a guide to the author's studies of Monetary Sys- tems." It was therefore undertaken with the sole object of estab- lishing with precision the dates of ancient history. -

Post Scriptum: a Number of Observations, with Hindsight

Post Scriptum: A Number of Observations, with Hindsight Astronomia Etrusco-Romana was first published in Italian in 2003, following Astronomy and Calendar in Ancient Rome—The Eclipse Festivals in 2001, and Le Feste di Venere—Fertilità femminile e configurazioni astrali nel calendario di Roma antica in 1996. In nigh on a decade of ‘‘crazy, desperate’’ study, as Giacomo Leopardi would have it, I have reconstructed a solid framework of the Roman calendar’s astronomical underpinnings, especially the Numan calendar. Stars, Myths and Rituals in Etruscan Rome makes only minimal adjustments to this framework, as well as adding some interesting elements to the fray. Over this time—and at long last—there has been a radical change in our understanding of man’s relationship with the heavens during the time of Rome’s early kings. The eighth century BCE calendars that have survived the centuries are no longer viewed as the basic calendars of an agricultural and pastoral society, lacking in any consideration for heavenly phenomena or the movements of heavenly bodies; calendar feast days are no longer considered simple anniversaries of natural events, such as storing away grain or lambing time. On the contrary, the Romulean calendar demonstrates an awareness of a number of significant celestial phenomena, while the Numan calendar and cycle are a highly advanced—indeed, close to perfect—mechanism for monitoring observable movements in the solar system. The end result of this research is a demonstration not just that Romans in Augustus’ day were mistaken in their belief—asserted time and time again by Ovid, our best witness1—that Romans were uninterested in and had no understanding of astronomy. -

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy’ 2016 Jillian Mitchell For Michael – and in memory of my father Kenneth who started it all Abstract for PhD Thesis in Classics The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus This thesis explores the last decades of legal paganism in the Roman Empire of the second half of the fourth century CE through the eyes of Symmachus, orator, senator and one of the most prominent of the pagans of this period living in Rome. It is a religious biography of Symmachus himself, but it also considers him as a representative of the group of aristocratic pagans who still adhered to the traditional cults of Rome at a time when the influence of Christianity was becoming ever stronger, the court was firmly Christian and the aristocracy was converting in increasingly greater numbers. Symmachus, though long known as a representative of this group, has only very recently been investigated thoroughly. Traditionally he was regarded as a follower of the ancient cults only for show rather than because of genuine religious beliefs. I challenge this view and attempt in the thesis to establish what were his religious feelings. Symmachus has left us a tremendous primary resource of over nine hundred of his personal and official letters, most of which have never been translated into English. These letters are the core material for my work. I have translated into English some of his letters for the first time.