Shakespeare's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Shakespeare (1564- 1616) He Was an English Poet and Playwright of the Elizabethan Period

William Shakespeare (1564- 1616) He was an English poet and playwright of the Elizabethan period. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon". He was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men. After the plagues of 1592–3, Shakespeare's plays were performed by his own company at The Theatre and the Curtain north of the Thames. When the company found themselves in dispute with their landlord, they pulled The Theatre down and used the timbers to construct the Globe Theatre, the first playhouse built by actors for actors, on the south bank of the Thames. 1610 portrait The Globe theatre opened in After the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, the company was awarded a 1599. royal patent by the new king, James I, and changed its name to the King's Men. Acting was considered dishonourable for women and women did not appear on the stage in England until the seventeenth century. In Shakespeare's plays, the roles of women were often played by young boys. His works consist of about 38 plays, 154 sonnets and several other poems. He produced most of his known work between 1589 and 1613. His early plays were mainly comedies and histories. He then wrote mainly tragedies until about 1608. -

On the Economic Origins of Constraints on Women's Sexuality

On the Economic Origins of Constraints on Women’s Sexuality Anke Becker* November 5, 2018 Abstract This paper studies the economic origins of customs aimed at constraining female sexuality, such as a particularly invasive form of female genital cutting, restrictions on women’s mobility, and norms about female sexual behavior. The analysis tests the anthropological theory that a particular form of pre-industrial economic pro- duction – subsisting on pastoralism – favored the adoption of such customs. Pas- toralism was characterized by heightened paternity uncertainty due to frequent and often extended periods of male absence from the settlement, implying larger payoffs to imposing constraints on women’s sexuality. Using within-country vari- ation across 500,000 women in 34 countries, the paper shows that women from historically more pastoral societies (i) are significantly more likely to have under- gone infibulation, the most invasive form of female genital cutting; (ii) are more restricted in their mobility, and hold more tolerant views towards domestic vio- lence as a sanctioning device for ignoring such constraints; and (iii) adhere to more restrictive norms about virginity and promiscuity. Instrumental variable es- timations that make use of the ecological determinants of pastoralism support a causal interpretation of the results. The paper further shows that the mechanism behind these patterns is indeed male absenteeism, rather than male dominance per se. JEL classification: I15, N30, Z13 Keywords: Infibulation; female sexuality; paternity uncertainty; cultural persistence. *Harvard University, Department of Economics and Department of Human Evolutionary Biology; [email protected]. 1 Introduction Customs, norms, and attitudes regarding the appropriate behavior and role of women in soci- ety vary widely across societies and individuals. -

Le Marchand De Venise » Et « Le Marchand De Venise De Shakespeare À Auschwitz » Marie-Christiane Hellot

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 19:34 Jeu Revue de théâtre De Shakespeare à Auschwitz « Le Marchand de Venise » et « Le Marchand de Venise de Shakespeare à Auschwitz » Marie-Christiane Hellot « Roberto Zucco » Numéro 69, 1993 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/29188ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc. ISSN 0382-0335 (imprimé) 1923-2578 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Hellot, M.-C. (1993). Compte rendu de [De Shakespeare à Auschwitz : « Le Marchand de Venise » et « Le Marchand de Venise de Shakespeare à Auschwitz »]. Jeu, (69), 168–176. Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc., 1993 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ De Shakespeare à Auschwitz «Le Marchand de Venise «Le Marchand de Venise» de Shakespeare à Auschwitz» Texte de William Shakespeare; traduction de Michelle Allen. Texte de William Shakespeare, Elie Wiesel et Tibor Egervari; Mise en scène : Daniel Roussel, assisté de Roxanne Henty; traduction de Shakespeare : François-Victor Hugo. Mise décor : Guy Neveu; costumes : Mérédith Caron; éclairages : en scène : Tibor Egervari; décor et éclairages ; Margaret Michel Beaulieu; musique : Christian Thomas. -

Introduction 1 the Chastity Belt

NOTES Introduction 1. David R. Reuben, Everthing You Always Wanted to Know about Sex* (But Were Afraid to Ask) (1969; New York: David McKay, 1970), 230. 2. Richard A. Schwartz, Woody, From Antz to Zelig: A Reference Guide to Woody Allen’s Creative Work, 1964–1998 ( Westport, CT, and London: Greenwood Press, 2000), 96; see also Foster Hirsch, Love, Sex, Death, and the Meaning Life: Woody Allen’s Comedy (New York, St. Louis, et al: McGraw-Hill, 1981), 65–70. 1 The Chastity Belt 1. There are many new studies on modern medievalism, see, for instance, Elizabeth Emery, Consuming the Past: The Medieval Revival in Fin-De-Siècle France (Aldershot, England, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003); The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy, ed. Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray ( Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland, 2004); Justin E. Griffin, The Grail Procession: The Legend, the Artifacts, and the Possible Sources of the Story ( Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland, 2004). The superficial approach to the past today, however, is not a new phenomenon, and medievalism certainly started already ca. 200 years ago, see Siegfried Grosse and Ursula Rautenberg, Die Rezeption mittelalterlicher deutscher Literatur: Eine Bibliographie ihrer Übersetzungen und Bearbeitungen seit der Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1989); Lorretta M. Holloway and Jennifer A. Palmgren, eds., Beyond Arthurian Romances: The Reach of Victorian Medievalism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). 2. Washington Irving, The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. The Works of Washington Irving, V (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1860), 109–10. 3. Irving, The Life, 110. 4. -

DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE Dossier Proposé Dans Le Cadre Du Dispositif Lycéens À L’Opéra, Financé Par La Région Rhône-Alpes

14/15 LE MARCHAND DE VENISE REYNALDO HAHN DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE Dossier proposé dans le cadre du dispositif Lycéens à l’Opéra, financé par la Région Rhône-Alpes. Dossier réalisé sous la direction d'Oumama Rayan Coordination Clarisse Giroud Rédaction des textes Jonathan Parisi CONTACT Mise en page et suivi de fabrication Aurélie Souillet Clarisse Giroud Document disponible en téléchargement sur Chargée de la médiation et de l'action culturelle www.operatheatredesaintetienne.fr 04 77 47 83 34 / [email protected] LE MARCHAND DE VENISE REYNALDO HAHN OPÉRA EN 3 ACTES ET 5 TABLEAUX LIVRET DE MIGUEL ZAMACOÏS D’APRÈS LA COMÉDIE DE SHAKESPEARE CRÉÉ À L’OPÉRA DE PARIS LE 25 MARS 1935 DIRECTION MUSICALE FRANCK VILLARD MISE EN SCÈNE, DÉCORS ET LUMIÈRES ARNAUD BERNARD ASSISTANT MISE EN SCÈNE GIANNI SANTUCCI ASSISTANT DÉCORS VIRGILE KOERING COSTUMES CARLA RICOTTI LUMIÈRES PATRICK MÉEUS CHEF DE chœur LAURENT TOUCHE CHEF DE CHANT CYRIL GOUJON ANTONIO FRÉDÉRIC GONCALVÈS SHYLOCK PIERRE-YVES PRUVOT BASSANIO GUILLAUME ANDRIEUX PORTIA GABRIELLE PHILIPONET GRATIANO FRANÇOIS ROUGIER LORENZO PHILIPPE TALBOT TUBAL HARRY PEETERS NÉRISSA ISABELLE DRUET JESSICA MAGALI ARNAULT-STANCZAK ANTONIO FRÉDÉRIC GONCALVÈS LA VOIX, LE PRINCE D’ARAGON, SALARINO VINCENT DELHOUME LE PRINCE DU MAROC, LE DOGE FRÉDÉRIC CATON L'AUDIENCIER, UN SERVITEUR FRÉDÉRIK PRÉVAULT LE GRAND DE VENISE ZOLTAN CSEKÖ UN SERVITEUR FRANÇOIS BESCOBO ORCHESTRE SYMPHONIQUE SAINT-ÉTIENNE LOIRE Chœur LYRIQUE SAINT-ÉTIENNE LOIRE GRAND THÉÂTRE MASSENET UNE HEURE AVANT CHAQUE REPRÉSENTATION, MERCREDI 27 MAI : 20H PROPOS D'AVANT SPECTACLE PAR JONATHAN VENDREDI 29 MAI : 20H PARISI, MUSICOLOGUE. DIMANCHE 31 MAI : 15H GRATUIT SUR PRÉSENTATION DE VOTRE BILLET. -

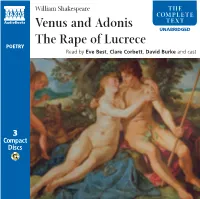

Venus and Adonis the Rape of Lucrece

NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 1 William Shakespeare THE COMPLETE Venus and Adonis TEXT The Rape of Lucrece UNABRIDGED POETRY Read by Eve Best, Clare Corbett, David Burke and cast 3 Compact Discs NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 2 CD 1 Venus and Adonis 1 Even as the sun with purple... 5:07 2 Upon this promise did he raise his chin... 5:19 3 By this the love-sick queen began to sweat... 5:00 4 But lo! from forth a copse that neighbours by... 4:56 5 He sees her coming, and begins to glow... 4:32 6 'I know not love,' quoth he, 'nor will know it...' 4:25 7 The night of sorrow now is turn'd to day... 4:13 8 Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey... 4:06 9 'Thou hadst been gone,' quoth she, 'sweet boy, ere this...' 5:15 10 'Lie quietly, and hear a little more...' 6:02 11 With this he breaketh from the sweet embrace... 3:25 12 This said, she hasteth to a myrtle grove... 5:27 13 Here overcome, as one full of despair... 4:39 14 As falcon to the lure, away she flies... 6:15 15 She looks upon his lips, and they are pale... 4:46 Total time on CD 1: 73:38 2 NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 3 CD 2 The Rape of Lucrece 1 From the besieged Ardea all in post.. -

Women's Masturbation: an Exploration of the Influence of Shame, Guilt, and Religiosity (Protocol #: 18712)

WOMEN’S MASTURBATION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE INFLUENCE OF SHAME, GUILT, AND RELIGIOSITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY AND PHILOSOPHY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY ANGELA HUNGRIGE, B.S., M.A. DENTON, TEXAS AUGUST 2016 1 DEDICATION To those who gave me courage. I will be forever grateful for the strength and support of the Fantastic Four. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not exist without the help and guidance from my Chair, Debra Mollen, Ph.D. She went above and beyond what was expected of her. She provided inspiration from the beginning of my doctoral experience with the classes she taught, which challenged preconceived notions and provided insight. Her support and patience was invaluable throughout my dissertation experience and gave me the courage to tackle a sensitive subject that intimidated me. Her calmness was invaluable when I needed encouragement, as was her feedback, which broadened my perspective and strengthened my writing. I feel honored for the experience of being able to work with her. Thank you. I am also grateful for the members of my dissertation committee, Sally Stabb, Ph.D., Jeff Harris, Ph.D., and Claudia Porras Pyland, Ph.D. Their support, insight, feedback, and enthusiasm have enriched my experience and improved my skills as a researcher, writer, and professional. I appreciate their willingness to participate and support me in my journey. I would also like to specially thank Lisa Rosen, Ph.D., for her help with my statistical analyses. -

Shakespeare's Rome

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15906-8 — Shakespeare Survey Edited by Peter Holland Excerpt More Information PAST THE SIZE OF DREAMING? SHAKESPEARE’SROME ROBERT S. MIOLA Ethereal Rumours citizens, its customs, laws and code of honour, its Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus enemies, wars, histories and myths. But (T. S. Eliot) Shakespeare knew Rome as a modern city of Italy as well, land of love, lust, revenge, intrigue and art, Confronting modernity, the speaker in setting or partial setting for eight plays. Portia dis- ‘ ’ The Wasteland recalled the ancient hero and guises herself as Balthazar, a ‘young doctor of ’ ‘ Shakespeare s play (his most assured artistic suc- Rome’ (Merchant, 4.1.152); Hermione’s statue is ’ cess , Eliot wrote elsewhere) as fragments of past said to be the creation of ‘that rare Italian master, grandeur momentarily shored against his present Giulio Romano’ (The Winter’s Tale, 5.2.96). And ruins. Contrarily, Ralph Fiennes revived Shakespeare knew both ancient and modern fi Coriolanus in his 2011 lm because he thought it Rome as the centre of Roman Catholicism, a modern political thriller: home of the papacy, locus of forbidden devotion For me it has an immediacy: I know that politician and prohibited practice, city of saints, heretics, getting out of that car. I know that combat guy. I’ve martyrs and miracles. The name ‘Romeo’, appro- seen him every day on the news and in the newspaper – priately, identifies a pilgrim to Rome. Margaret that man in that camouflage uniform running down the wishes the college of Cardinals would choose her street, through the smoke and the dust. -

Rape of Lucretia) Tears Harden Lust, Though Marble Wear with Raining./...Herpity-Pleading Eyes Are Sadly Fix’D/In the Remorseless Wrinkles of His Face

ART AND IMAGES IN PSYCHIATRY SECTION EDITOR: JAMES C. HARRIS, MD Tarquin and Lucretia (Rape of Lucretia) Tears harden lust, though marble wear with raining./...Herpity-pleading eyes are sadly fix’d/In the remorseless wrinkles of his face... She conjures him by high almighty Jove/...Byheruntimely tears, her husband’s love,/By holy hu- man law, and common troth,/By heaven and earth and all the power of both,/That to his borrow’d bed he make retire,/And stoop to honor, not to foul desire.1(p17) UCRETIA WAS A LEGENDARY HEROINE OF ANCIENT shadow so his expression is concealed as he rips off Lucretia’s Rome, the quintessence of virtue, the beautiful wife remaining clothing. Lucretia physically resists his violence and of the nobleman Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus.2 brutality. A sculpture decorating the bed has fallen to the floor, In a lull in the war at Ardea in 509 BCE, the young the sheets are in disarray, and Lucretia’s necklace is broken, noblemen passed their idle time together at din- her pearls scattered. Both artists transmit emotion to the viewer, Lners and in drinking bouts. When the subject of their wives came Titian through her facial expression and Tintoretto in the vio- up, every man enthusiastically praised his own, and as their ri- lent corporeal chaos of the rape itself. valry grew, Collatinus proposed that they mount horses and see Lucretia survived the rape but committed suicide. After en- the disposition of the wives for themselves, believing that the best during the rape, she called her husband and her father to her test is what meets his eyes when a woman’s husband enters un- and asked them to seek revenge. -

Airs Et Mélodies

LIVINE MERTENS Airs et mélodies MENU Tracklist p.4 Français p.10 English p.18 Nederlands p.26 Deustch p.36 LIVINE MERTENS Mezzo-soprano (Anvers, 1898 – Bruxelles, 1968) Airs et mélodies BOÏELDIEU François-Adrien (1775-1834) 1 « D’ici voyez ce beau domaine », Couplets de Jenny, dans La dame blanche (I, 5), 3’02 chœurs et orchestre du Théâtre royal de la Monnaie, dir. Maurice Bastin (Columbia RF29–WLB128) [ULB] THOMAS Ambroise (1811-1896) 2 « Connais-tu le pays ? », Cantabile de Mignon (I), 4’20 orchestre du Théâtre royal de la Monnaie, dir. Maurice Bastin (Columbia RFX30–LBX73) [KBR : Becko V/8/2b Mus] MASSENET Jules (1842-1912) 3 « Va ! laisse couler mes larmes », air de Charlotte dans Werther (III, 2), 2’28 avec accompagnement de piano (Edison 89259–F374) [KBR : Becko V/57/13 Mus] BIZET Georges (1838-1875) 4 « L’amour est un oiseau rebelle », Habanera de Carmen (I, 5), 2’43 avec accompagnement de piano (Edison 89257–F373) [KBR : Becko V/57/11a Mus] 5 « Près des remparts de Séville », Séguedille de Carmen (I, 10), 1’51 avec accompagnement de piano (Edison 89258–F373) [KBR : Becko V/57/11b Mus] GOUNOD Charles (1818-1893) 6 « Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle », Chanson de Stéphano, dans Roméo et Juliette (III, 2e tableau) 2’44 avec accompagnement de piano (Edison 89260–F374) [ULB] 7 « Depuis hier je cherche en vain mon maître » – « Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle », Chanson de Stéphano, dans Roméo et Juliette (III, 2e tableau), 4’09 orchestre du Théâtre royal de la Monnaie, dir. Maurice Bastin (Columbia RFX30–LBX74) [KBR: Becko V/8/2a MUS] OFFENBACH Jacques (1819-1880) 8 « Voici le sabre de mon père », Couplets de La grande duchesse de Gérolstein (I, 13), 3’12 chœurs et orchestre du Théâtre royal de la Monnaie, dir. -

Rape and Resistance of Lavinia in Titus Andronicus

Texture: A Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 2017 The Body that Writes: Rape and Resistance of Lavinia in Titus Andronicus Arnab Baul Assistant Professor of English Surya Sen College, Siliguri Abstract The violent rape of a woman is at the centre of Shakespeare’s early tragedy ‘Titus Andronicus’. The gang rape of Titus’ daughter Lavinia unsettles our civilized sensibility in terms of its brutality and raises questions regarding rape’s appropriation in socio-cultural space. The play shows, as I argue here, how the violated body of Lavinia has become a site of contestation representing a struggle between Roman patriarchy’s attempted construction of narrative of shame and Lavinia’s courageous rebuttal. Lavinia’s subversion of this strategy of gender stratification by speaking through language of silence and then using writing as performance, shows a rape victim’s regaining of her lost self.The narrative of rape and revenge thus turns into a narrative of resistance when more than the act of violation it is the consequence of violation of the body and the resultant trauma which is highlighted. This paper further shows that an environment that makes it shameful to speak of rape, disallows a critique of rape and the culture that sustains it. I conclude by suggesting that the death of Lavinia, even after registering her protest, bursts forth the state of crafty amnesia of a society which still is befuddled on the issue of appropriating rape both culturally and psychologically. Keywords: Rape, patriarchy, gender-construction, protest, befuddlement And that deep torture may be call’d a hell, When more is felt than one hath power to tell. -

86 Women Under Siege. the Shakespearean Ethics Of

DOI: 10.2478/v10320-012-0030-9 WOMEN UNDER SIEGE. THE SHAKESPEAREAN ETHICS OF VIOLENCE DANA PERCEC and ANDREEA ŞERBAN West University of Timișoara 4, Pârvan Blvd, Timișoara, Romania [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses notions of physical violence, domestic violence, and sexual assault and the ways in which these were socially and legally perceived in early modern Europe. Special attention will be paid to a number of Shakespearean plays, such as Titus Andronicus and Edward III, but also to the narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece (whose motifs were later adopted in Cymbeline), where the consumption of the female body as a work of art is combined with verbal and physical abuse. Key words: consumption, rape, sexual assault, siege, violence Introduction The fourth act of William Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus opens with the raped and mutilated Lavinia chasing Lucius’ son, gesturing at the book in the boy’s hand, Ovid’s Metamorphoses. She manages to turn the pages to the story of the rape of Philomela, thus informing her father and uncle about Tamora’s sons’ deeds. Starting from this scene, which is one of Ovid’s most prominent influences on Shakespeare’s plays, the paper will discuss notions of physical violence, domestic violence and sexual assault and the way in which they are socially and legally perceived in premodern and early modern Europe. Special attention will be paid to such Shakespearean plays as Titus Andronicus and Edward III, probably the best example of sexual harassment in early modern fiction, but also to the narrative poem The Rape of Lucrece (whose motifs were later adopted in 86 Cymbeline), where the consumption of the female body as a work of art is combined with verbal and physical abuse.