Police Defunding and Reform : What Changes Are Needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Divided Beliefs Behind a Seemingly United Movement an Ipsos POV in Diversity & Inclusion

I CAN’T BREATHE: The Divided Beliefs Behind a Seemingly United Movement An Ipsos POV in Diversity & Inclusion By Marie Lemay, James Diamond, and Nina Seminara May 25 marks the one-year anniversary of the killing of George Floyd, an event that sparked outrage against police brutality—particularly toward Black people—in Floyd’s hometown of Minneapolis. Soon after, Americans in over 2,000 cities across all 50 states began organizing demonstrations, with protests extending beyond America’s borders to all corners of the world. Though most of the protests were peaceful, there were instances of violence, vandalism, destruction and death in several cities, provoking escalated police intervention, curfews and in some cases, the mobilization of the National Guard. The nationwide engagement with the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the 2020 protests, and data from a survey conducted nearly a year later showing 71% of Americans believed Chauvin is guilty of murder, paint the picture of a seem- ingly united people. ENGAGEMENT WITH THE GEORGE FLOYD PROTESTS MADE IT CLEAR THAT MANY AMERICANS ACROSS THE NATION ARE NO LONGER WILLING TO TOLERATE RACIAL INJUSTICE. Key Takeaways: • However, major gaps in perception exist when comparing how Black and White Americans understood and perceived the 2020 protests. • Ipsos conducted several national surveys throughout the duration of the Black Lives Matter protests to gain a sense of Americans’ attitudes and opinions towards the events that unfolded. Here’s what we found. 2 IPSOS | I CAN’T BREATHE: THE DIVIDED BELIEFS BEHIND A SEEMINGLY UNITED MOVEMENT What is your personal view on the Do you support or oppose the protests circumstances around the death and demonstrations taking place of George Floyd in Minneapolis? across the country following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis? % It was murder. -

Excessive Use of Force by the Police Against Black Americans in the United States

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Written Submission in Support of the Thematic Hearing on Excessive Use of Force by the Police against Black Americans in the United States Original Submission: October 23, 2015 Updated: February 12, 2016 156th Ordinary Period of Sessions Written Submission Prepared by Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Global Justice Clinic, New York University School of Law International Human Rights Law Clinic, University of Virginia School of Law Justin Hansford, St. Louis University School of Law Page 1 of 112 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary & Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Pervasive and Disproportionate Police Violence against Black Americans ..................................................................... 21 A. Growing statistical evidence reveals the disproportionate impact of police violence on Black Americans ................. 22 B. Police violence against Black Americans compounds multiple forms of discrimination ............................................ 23 C. The treatment of Black Americans has been repeatedly condemned by international bodies ...................................... 25 D. Police killings are a uniquely urgent problem ............................................................................................................. 25 II. Legal Framework Regulating the Use of Force by Police ................................................................................................ -

1. Petitions to Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4

Disclaimer and Credit: This is by no means comprehensive, but rather a list we hope you find helpful as a starting point to begin or to continue to support our Black brothers, sisters, communities and patients. Thank you to the Student National Medical Association chapter at George Washington University School of Medicine for compiling many of these resources. Editing Guidelines: Please feel free to add any resources that you feel are useful. Any inappropriate edits will be deleted and editing capabilities will be revoked. Table of Contents 1. Petitions To Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4. Mental Health Resources 5. Anti-Racism Reading and Resource List 6. Media 7. Voter Registration and Related Information 8. How to Support Memphis 1. Petitions To Sign *Please note that should you decide to sign a petition on change.org, DO NOT donate through change.org. Rather, donate through the websites specific to the organizations to ensure your donated funds are going directly to the organization. ● Justice for George Floyd ● Justice for Breonna ● Justice for Ahmaud Arbery ● We Can’t Breathe ● Justice for George Floyd 2. Protestor Bail Funds ● National Bail Fund Network (by state) ○ This link includes links to various cities ● Restoring Justice (Legal & Social services) 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations Actions are loud. As students, we know that money is tight. But if each of us donated just $5 to one cause, together we could demand a great impact. ● Black Visions Collective (Minnesota Based): “BLVC is committed to a long term vision in which ALL Black lives not only matter, but are able to thrive. -

Fresno-Commission-Fo

“If you are working on a problem you can solve in your lifetime, you’re thinking too small.” Wes Jackson I have been blessed to spend time with some of our nation’s most prominent civil rights leaders— truly extraordinary people. When I listen to them tell their stories about how hard they fought to combat the issues of their day, how long it took them, and the fact that they never stopped fighting, it grounds me. Those extraordinary people worked at what they knew they would never finish in their lifetimes. I have come to understand that the historical arc of this country always bends toward progress. It doesn’t come without a fight, and it doesn’t come in a single lifetime. It is the job of each generation of leaders to run the race with truth, honor, and integrity, then hand the baton to the next generation to continue the fight. That is what our foremothers and forefathers did. It is what we must do, for we are at that moment in history yet again. We have been passed the baton, and our job is to stretch this work as far as we can and run as hard as we can, to then hand it off to the next generation because we can see their outstretched hands. This project has been deeply emotional for me. It brought me back to my youthful days in Los Angeles when I would be constantly harassed, handcuffed, searched at gunpoint - all illegal, but I don’t know that then. I can still feel the terror I felt every time I saw a police cruiser. -

Blacklivesmatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 #BlackLivesMatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Naomi Mezey Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Lisa O. Singh Georgetown University, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2387 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3860435 California Law Review Online, Vol. 12, Reckoning and Reformation symposium. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons #BlackLivesMatter— Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams*, Naomi Mezey**, and Lisa Singh*** Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 I. Methodology ............................................................................................ 5 II. BLM: From Contemporary Social Movement to Structural Change ..... 6 A. Black Lives Matter as a Social Media Powerhouse ................. 6 B. Tweets and Streets: The Dynamic Relationship between Online and Offline Activism ................................................. 12 C. A Theory of How to Move from Social Media -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

Black Lives Matter Syllabus

Black Lives Matter: Race, Resistance, and Populist Protest New York University Fall 2015 Thursdays 6:20-9pm Professor Frank Leon Roberts Fall 2015 Office Hours: (By Appointment Only) 429 1 Wash Place Thursdays 1:00-3:00pm, 9:00pm-10:00pm From the killings of teenagers Michael Brown and Vonderrick Myers in Ferguson, Missouri; to the suspicious death of activist Sandra Bland in Waller Texas; to the choke-hold death of Eric Garner in New York, to the killing of 17 year old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida and 7 year old Aiyana Stanley-Jones in Detroit, Michigan--. #blacklivesmatter has emerged in recent years as a movement committed to resisting, unveiling, and undoing histories of state sanctioned violence against black and brown bodies. This interdisciplinary seminar links the #blacklivesmatter” movement to four broader phenomena: 1) the rise of the U.S. prison industrial complex and its relationship to the increasing militarization of inner city communities 2) the role of the media industry (including social media) in influencing national conversations about race and racism and 3) the state of racial justice activism in the context of a purportedly “post-racial” Obama Presidency and 4) the increasingly populist nature of decentralized protest movements in the contemporary United States (including the tea party movement, the occupy wall street movement, etc.) Among the topics of discussion that we will debate and engage this semester will include: the distinction between #blacklivesmatter (as both a network and decentralized movement) vs. a broader twenty first century movement for black lives; the moral ethics of “looting” and riotous forms of protest; violent vs. -

In Solidarity — a Note from Shelly

June 4, 2020: In Solidarity — A Note from Shelly Dear CDS Family, As a white person, no matter how closely I am an observer, I will NEVER understand the suffering in our Black community. What we are witnessing now is the manifestation of years of pain, trauma, and the pushing down of emotions in response to systemic state-sanctioned racial violence and police brutality. At this moment, the pain is present and acute. The critical way forward is to keep the observance of this pain in mind as we navigate the next steps individually and collectively. For some additional learning and perspective, watch the film Just Mercy (streaming for free this month) and Bryan Stevenson’s follow-up TED talk. As a faculty and staff community, we have committed to putting our resources where they can help. Together, we have donated more than $4,100 to the organizations listed at the bottom of this email. Some have made monthly commitments and others are first-time connections to organizations which may become a lifelong philanthropic focus. We encourage you and your family to donate what you can to organizations defending and celebrating Black lives as well as individuals in your community who are in need. Another opportunity to stand up is to support Black-owned restaurants in the Bay Area with your business. I thought this article would resonate with you as you support your children and yourself in unpacking this complex topic of race. Woke Kindergarten’s Word of the Day - Protest offers young children an age-appropriate perspective on the protests and can be a catalyst to start or continue your conversations at home. -

What Is Police Violence? Plain Language Toolkit

What is Police Violence? A plain language booklet about anti-Black racism, police violence, and what you can do to stop it 1 Introduction We are writing this booklet in June of 2020. Right now, there are protests all over the country about racism and police violence. We wrote this booklet in plain language so as many people as possible can understand the protests. There is a lot to know about racism and police violence. We can’t talk about everything in this short booklet. We will tell you where to learn more. And, we will work on more resources. This booklet is just to get you started. Racism is when people are treated unfairly because of their race. Anti-Black racism is when Black people are treated unfairly because they are Black. People can do racist things. For example: Byron is Black. He wants to rent a house. Tyler is white. He owns a house, and wants to rent it out. Byron comes to see Tyler’s house. Tyler lies to Byron because Byron is Black. Tyler tells Byron that the house is not up for rent. Tyler only wants to rent his house to white people. Tyler was being racist when he lied to Byron. Society does racist things. For example: There are many times where a Black person and a white person do the same crime. Usually, the Black person will go to jail for longer. The white person might not even go to jail! The way our society deals with crime is racist. It is set up to hurt Black people. -

Final List George Floyd

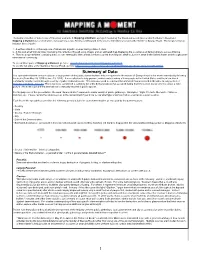

The below collection of data is one of three key elements in Mapping a Moment, a project created by the Cleveland based musical duo the Baker’s Basement. Mapping a Moment was crafted after a long journey across America and beyond in the weeks immediately following the murder of George Floyd. The full presentation includes these 3 parts: 1. A written reflection on the response of Americans in public spaces during a time of crisis 2. A five and a half minute video illustrating this reflection through song, image, and an animated map displaying the occurrence of demonstrations across America 3. The below spreadsheet containing data on over 1600 public demonstrations that occurred from May 25, 2020 to June 13, 2020 in the United States and throughout the international community. To see all three parts of Mapping a Moment, go here: www.thebakersbasement.com/mapping-a-moment To see the full video of the murder of George Floyd, go here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zaGmz4DPlJw&app=desktop&bpctr=1596415559 Summary of Data: The spreadsheet below contains data on a large portion of the public demonstrations held in response to the murder of George Floyd in the weeks immediately following his death (From May 25, 2020 to June 13, 2020). It was collected to help provide a wider understanding of how people in the United States and the international community initially reacted through a variety of public demonstrations. This data was used to construct the animated map presented in the video & song portion of Mapping a Moment - Youtube. This is not to be considered a complete list of the demonstrations that occurred during that time period, but an effort to create a fuller picture of how the USA and the international community reacted in public spaces. -

Struggle for Power: the Ongoing Persecution of Black Movement the by U.S

STRUGGLE FOR POWER T H E ONGOING PERSECUTION O F B L A C K M O V E M E N T BY THE U.S. GOVERNMENT In the fight for Black self-determination, power, and freedom in the United States, one institution’s relentless determination to destroy Black movement is unrivaled— the United States federal government. Black resistance and power-building threaten the economic interests and white supremacist agenda that uphold the existing social order. Throughout history, when Black social movements attract the nation’s or world’s attention, or we fight our way onto the nation’s political agenda as we have today, we experience violent repression. We’re disparaged and persecuted; cast as villains in the story of American prosperity; and forced to defend ourselves and our communities against police, anti-Black policymakers, and U.S. armed forces. Last summer, on the heels of the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, millions of people mobilized to form the largest mass movement against police violence and racial injustice in U.S. history. Collective outrage spurred decentral- ized uprisings in defense of Black lives in all 50 states, with a demand to defund police and invest in Black communities. This brought global attention to aboli- tionist arguments that the only way to prevent deaths such as Mr. Floyd’s and Ms. Taylor’s is to take power and funding away from police. At the same time, the U.S federal government, in a flagrant abuse of power and at the express direction of disgraced former President Donald Trump and disgraced former Attorney General William Barr, deliberately targeted supporters of the movement to defend Black lives in order to disrupt and discourage the movement. -

Dialogue Session Resources

Dialogue Session Resources This document is not exhaustive of resources to fight police brutality, organizations to follow on social media, resources for addressing racism and for engaging in anti-racism work and practicing solidarity Resources for Fighting Police Brutality ● https://www.joincampaignzero.org/ ● https://www.obama.org/wp-content/uploads/Toolkit.pdf ● https://www.aclu.org/other/fighting-police-abuse-community-action-manual A summary of research-based solutions to stop police violence from Data Scientist & Policy Analyst Samuel Sinyangwe: https://twitter.com/samswey/status/1180655701271732224 A Physician/Activist, Dr. Quinn Capers IV introduces some of his medical role models that were also activists for African American civil rights and calls all of us to use our careers to create positive change. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5y5nPSjNNZs&app=desktop This link provides resources compiled by Autumn Gupta with Bryanna Wallace’s oversight for the purpose of providing a starting place for individuals trying to become better allies. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1H- Vxs6jEUByXylMS2BjGH1kQ7mEuZnHpPSs1Bpaqmw0/mobilebasic Organizations to follow on social media: ● Antiracism Center: Twitter ● Audre Lorde Project: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook ● Black Women’s Blueprint: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook ● Color Of Change: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook ● Colorlines: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook ● The Conscious Kid: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook ● Equal Justice Initiative (EJI): Twitter | Instagram | Facebook ● Families Belong