Research Evaluation of the City of Columbus' Response to the 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Striving for Anti-Racism: a Beginner's Journal!

Striving For Anti-Racism: A Beginner’s Journal BY BEYOND THINKING Special Thanks Anti-racism work does not happen in a vacuum. This journal would not be possible without the brilliance of Jennifer Wong, Karimah Edwards, Kyana Wheeler, Lauren Kite, and Cat Cuevas. Jennifer Wong, Creative Designer Attorney, and also the love of my life (!) Karimah Edwards, Editor Hummingbird Cooperative Kyana Wheeler, Anti-Racist Consultant and Advisor Kyana Wheeler Consulting Lauren Kite, Anti-Racist Consultant and Advisor Cat Cuevas, Anti-Racist Consultant and Advisor Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................4 How to Use This Journal........................................................ 7 I. WORKSHEETS & RESOURCES ................................. 9 Values ........................................................................................10 Emotions ................................................................................. 12 Racial Anxiety Self-Assessment (Round 1) .......14 Biases ........................................................................................ 16 Cultural Lenses ................................................................... 17 Privileges .................................................................................18 Privilege Bingo.................................................................... 19 Microaggressions .............................................................20 Common Forms of Resistance .............................. -

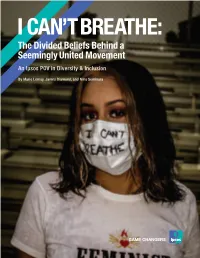

The Divided Beliefs Behind a Seemingly United Movement an Ipsos POV in Diversity & Inclusion

I CAN’T BREATHE: The Divided Beliefs Behind a Seemingly United Movement An Ipsos POV in Diversity & Inclusion By Marie Lemay, James Diamond, and Nina Seminara May 25 marks the one-year anniversary of the killing of George Floyd, an event that sparked outrage against police brutality—particularly toward Black people—in Floyd’s hometown of Minneapolis. Soon after, Americans in over 2,000 cities across all 50 states began organizing demonstrations, with protests extending beyond America’s borders to all corners of the world. Though most of the protests were peaceful, there were instances of violence, vandalism, destruction and death in several cities, provoking escalated police intervention, curfews and in some cases, the mobilization of the National Guard. The nationwide engagement with the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the 2020 protests, and data from a survey conducted nearly a year later showing 71% of Americans believed Chauvin is guilty of murder, paint the picture of a seem- ingly united people. ENGAGEMENT WITH THE GEORGE FLOYD PROTESTS MADE IT CLEAR THAT MANY AMERICANS ACROSS THE NATION ARE NO LONGER WILLING TO TOLERATE RACIAL INJUSTICE. Key Takeaways: • However, major gaps in perception exist when comparing how Black and White Americans understood and perceived the 2020 protests. • Ipsos conducted several national surveys throughout the duration of the Black Lives Matter protests to gain a sense of Americans’ attitudes and opinions towards the events that unfolded. Here’s what we found. 2 IPSOS | I CAN’T BREATHE: THE DIVIDED BELIEFS BEHIND A SEEMINGLY UNITED MOVEMENT What is your personal view on the Do you support or oppose the protests circumstances around the death and demonstrations taking place of George Floyd in Minneapolis? across the country following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis? % It was murder. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Southwest Area Plan City of Columbus - Franklin Township - Jackson Township :: Franklin County, Ohio

Southwest Area Plan City of Columbus - Franklin Township - Jackson Township :: Franklin County, Ohio City of Columbus Department of Development Planning Division Southwest Area Plan City of Columbus · Franklin Township · Jackson Township :: Franklin County, Ohio City of Columbus Mayor Michael B. Coleman Columbus City Council Commissioners Michael C. Mentel Paula Brooks Hearcel F. Craig Marilyn Brown Andrew J. Ginther John O’Grady A. Troy Miller Eileen Y. Paley Charleta B. Tavares Priscilla R. Tyson Franklin Township Board of Trustees Jackson Township Board of Trustees Timothy Guyton David Burris Don Cook Stephen Bowshier Paul Johnson William Lotz Sr. Bonnie Watkinson, Fiscal Officer William Forrester, Fiscal Officer iv Letter from the Directors In the spirit of regional cooperation and coordination, we respectively present the South- west Area Plan to both the Columbus City Council and the Franklin County Board of Commissioners. The plan is a result of a collaborative process among the city of Colum- bus, Franklin County, Franklin Township, Jackson Township, the Southwest Area Com- mission and the many interested citizens and stakeholders in the Southwest Area. The plan outlines a common vision for the future development of the Southwest Area that is a result of extensive community input and outreach to all of the area’s jurisdictions. The plan contains key recommendations in the areas of land use, parks and open spaces, economic development, urban design, transportation and regional coordination. The plan will be implemented cooperatively by the area’s jurisdictions and the Southwest Area Commission through the review of rezoning applications and the planning of future public improvements and initiatives. -

Systemic Racism, Police Brutality of Black People, and the Use of Violence in Quelling Peaceful Protests in America

SYSTEMIC RACISM, POLICE BRUTALITY OF BLACK PEOPLE, AND THE USE OF VIOLENCE IN QUELLING PEACEFUL PROTESTS IN AMERICA WILLIAMS C. IHEME* “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” —Martin Luther King Jr Abstract: The Trump Administration and its mantra to ‘Make America Great Again’ has been calibrated with racism and severe oppression against Black people in America who still bear the deep marks of slavery. After the official abolition of slavery in the second half of the nineteenth century, the initial inability of Black people to own land, coupled with the various Jim Crow laws rendered the acquired freedom nearly insignificant in the face of poverty and hopelessness. Although the age-long struggles for civil rights and equal treatments have caused the acquisition of more black-letter rights, the systemic racism that still perverts the American justice system has largely disabled these rights: the result is that Black people continue to exist at the periphery of American economy and politics. Using a functional approach and other types of approach to legal and sociological reasoning, this article examines the supportive roles of Corporate America, Mainstream Media, and White Supremacists in winnowing the systemic oppression that manifests largely through police brutality. The article argues that some of the sustainable solutions against these injustices must be tackled from the roots and not through window-dressing legislation, which often harbor the narrow interests of Corporate America. Keywords: Black people, racism, oppression, violence, police brutality, prison, bail, mass incarceration, protests. Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION: SLAVE TRADE AS THE ENTRY POINT OF SYSTEMIC RACISM. -

Police Defunding and Reform : What Changes Are Needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan

® About the Authors Olivia Ghafoerkhan is a nonfiction writer who lives in northern Virginia. She is the author of several nonfiction books for teens and young readers. She also teaches college composition. Hal Marcovitz is a former newspaper reporter and columnist who has written more than two hundred books for young readers. He makes his home in Chalfont, Pennsylvania. © 2021 ReferencePoint Press, Inc. Printed in the United States For more information, contact: ReferencePoint Press, Inc. PO Box 27779 San Diego, CA 92198 www.ReferencePointPress.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, web distribution, or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. Picture Credits: Cover: ChameleonsEye/Shutterstock.com 28: katz/Shutterstock.com 6: Justin Berken/Shutterstock.com 33: Vic Hinterlang/Shutterstock.com 10: Leonard Zhukovsky/Shutterstock.com 37: Maury Aaseng 14: Associated Press 41: Associated Press 17: Imagespace/ZUMA Press/Newscom 47: Tippman98x/Shutterstock.com 23: Associated Press 51: Stan Godlewski/ZUMA Press/Newscom LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING- IN- PUBLICATION DATA Names: Ghafoerkhan, Olivia, 1982- author. Title: Police defunding and reform : what changes are needed? / by Olivia Ghafoerkhan. Description: San Diego, CA : ReferencePoint Press, 2021. | Series: Being Black in America | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020048103 (print) | LCCN 2020048104 (ebook) | ISBN 9781678200268 (library binding) | ISBN 9781678200275 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Police administration--United States--Juvenile literature. | Police brutality--United States--Juvenile literature. | Discrimination in law enforcement--United States--Juvenile literature. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

Demonstrations, Demoralization, and Depolicing

Demonstrations, Demoralization, and Depolicing Christopher J. Marier Lorie A. Fridell University of South Florida Direct correspondence to Christopher J. Marier, Department of Criminology, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Ave. SOC107, Tampa, FL 33620 (email: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2445-6315). Christopher J. Marier is a PhD candidate at the University of South Florida. His areas of interest include race and justice, policing, and cross-national research. He is a recipient of the University of South Florida Graduate Fellowship Award. Lorie A. Fridell is Professor of Criminology at the University of South Florida, former Director of Research at the Police Executive Research Forum, and CEO of Fair and Impartial Policing, a national law enforcement training program. NOTE: Draft version 1.1, 8/10/2019. This paper has not been peer reviewed. This paper has not yet been published and is therefore not the authoritative document of record. Please do not copy or cite without authors’ permission. DEMONSTRATIONS, DEMORALIZATION & DEPOLICING 1 Abstract Research Summary This study examined relationships between public antipathy toward the police, demoralization, and depolicing using pooled time-series cross-sections of 13,257 surveys from law enforcement officers in 100 U.S. agencies both before and after Ferguson and contemporaneous demonstrations. The results do not provide strong support for Ferguson Effects. Post-Ferguson changes to job satisfaction, burnout, and cynicism (reciprocated distrust) were negligible, and while Post-Ferguson officers issued fewer citations, they did not conduct less foot patrol or attend fewer community meetings. Cynicism, which was widespread both before and after Ferguson, was associated with less police activity of all types. -

Blacklivesmatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 #BlackLivesMatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Naomi Mezey Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Lisa O. Singh Georgetown University, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2387 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3860435 California Law Review Online, Vol. 12, Reckoning and Reformation symposium. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons #BlackLivesMatter— Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams*, Naomi Mezey**, and Lisa Singh*** Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 I. Methodology ............................................................................................ 5 II. BLM: From Contemporary Social Movement to Structural Change ..... 6 A. Black Lives Matter as a Social Media Powerhouse ................. 6 B. Tweets and Streets: The Dynamic Relationship between Online and Offline Activism ................................................. 12 C. A Theory of How to Move from Social Media -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

The Great American Read Starts Tuesday, May 22 at 8Pm Details on Page 6 All Programs Are Subject to Change

May 2018 • wosu.org The Great American Read Starts Tuesday, May 22 at 8pm details on page 6 All programs are subject to change. VOLUME 39 • NUMBER 5 Airfare (UPS 372670) is published except for June, July and August by: WOSU Public Media 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 614.292.9678 Copyright 2018 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in any form or by any means without express written NPR political reporter Asma Khalid permission from the publisher. Subscription is by a minimum contribution of $60 to WOSU Public Media, of which $3.25 is allocated to Airfare. Periodicals postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Airfare, May 24 Dialogue: 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 WOSU Public Media Excuse me, is that seat taken? General Manager Tom Rieland A Look at Women in Ohio Politics Director of Marketing Meredith Hart & Communications Membership Rob Walker Inspired by the 2017 Women’s March on Washington, the #MeToo movement and other forces, 2018 is shaping up to be a record year Friends of WOSU Board President Bill Schiffman for women running for elected office. Rutgers University’s Center for Vice President Kathy McGinnis American Women and Politics counts 309 women running for seats in Secretary/Treasurer Kyle Anderson the US House, 29 women running for US Senate and 40 women running Board Members in governors’ races. William Ballenger Mac Joseph Among Ohio elected officials, the gender gap remains wide. Even Ann DiMarco Ray LaVoie Jeri Grier Ed Lentz though women make up the majority of the population, they remain in Fred Hadley Christine Mortine Dale Heydlauff Stacy Rastauskas the minority in public office. -

Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: from Elian to the Internment

Fordham Law Review Volume 70 Issue 6 Article 18 2002 Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment Andrew E. Taslitz Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew E. Taslitz, Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment, 70 Fordham L. Rev. 2257 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol70/iss6/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment Cover Page Footnote Visiting Professor, Duke University Law School, 2000-01; Professor of Law, Howard University School of Law; J.D., University of Pennsylvania School of Law, 1981, former Assistant District Attorney, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I thank my wife, Patricia V. Sun, Esq., Professors Robert Mosteller, Sara Sun-Beale, Girardeau Spann, joseph Kennedy, Eric Muller, Ronald Wright, and many other members of the Triangle Criminal Law Working Group, for their comments on early drafts of this Article. I also thank my research assistants, Nicole Crawford, Eli Mazur, and Amy Pope, and my secretary, Ann McCloskey. Appreciation also goes to the Howard University School of Law for funding this project, and to the Duke University Law School for helping me see this effort through to its completion.