The Belfast Project: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Division and the City: Spatial Dramas of Divided Cities

ARTICLE MEGARON 2015;10(4):565-579 DOI: 10.5505/MEGARON.2015.29290 Division and the City: Spatial Dramas of Divided Cities Bölünme ve Kent: Bölünmüş Kentlerin Mekânsal Trajedileri Gizem CANER ABSTRACT ÖZ Every contemporary city is divided to a certain extent. The Günümüz şehirlerinin neredeyse tamamı kavramsal bağlam- present study is concerned with urban division defined by da bir düzeye kadar bölünmüştür. Ancak bu yazı, milliyet, extreme tensions related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, etnisite, din ve kültürle ilişkili uç gerilimlerin neden olduğu, and culture, which are channelled into urban arenas. Once daha spesifik bir kentsel bölünme türüyle ilgilenmektedir. Bu these contestations are made spatially visible, the “divided çatışmalar kentsel alanlarda ses bulmaktadır ve mekânsal city” with which this study is concerned appears. Well-known görünürlük kazandıkları zaman, bu yazının da konusu olan examples of such “divided” cities are Belfast, Jerusalem, Nic- ‘bölünmüş kentler’ ortaya çıkmaktadır. Bu şehirler arasında osia, Mostar, Beirut, and Berlin. Due to distinctive attributes, en iyi bilinen örnekler Belfast, Kudüs, Lefkoşa, Mostar, Bey- these cities contain an exclusive discourse that differentiates rut ve Berlin’dir. Özgün niteliklerinden dolayı, bu şehirler, them from other urban areas. In this context, the aim of the kendilerini diğer kentsel alanlardan ayıran özel bir söyleme present study was to comparatively analyze urban conse- sahiptirler. Bu çerçevede, bu yazının ana konusu, seçilmiş quences of division in selected case studies: Belfast and Ber- şehir örneklerinde–Belfast ve Berlin–bölünmenin kentsel so- lin. As each city has unique attributes of geography, history, nuçlarının karşılaştırmalı olarak analiz edilmesidir. Her kent, and economic development, the processes and outcomes of kendine has coğrafi, tarihi ve ekonomik gelişme özelliklerine their division differ substantially. -

EAA Meeting 2016 Vilnius

www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME Organisers CONTENTS President Words .................................................................................... 5 Welcome Message ................................................................................ 9 Symbol of the Annual Meeting .............................................................. 13 Commitees of EAA Vilnius 2016 ............................................................ 14 Sponsors and Partners European Association of Archaeologists................................................ 15 GENERAL PROGRAMME Opening Ceremony and Welcome Reception ................................. 27 General Programme for the EAA Vilnius 2016 Meeting.................... 30 Annual Membership Business Meeting Agenda ............................. 33 Opening Ceremony of the Archaelogical Exhibition ....................... 35 Special Offers ............................................................................... 36 Excursions Programme ................................................................. 43 Visiting Vilnius ............................................................................... 57 Venue Maps .................................................................................. 64 Exhibition ...................................................................................... 80 Exhibitors ...................................................................................... 82 Poster Presentations and Programme ........................................... -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Woodford, I., & Smith, M. L. R. (2017). The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA – A Revision. STUDIES IN CONFLICT AND TERRORISM. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2017.1283195 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

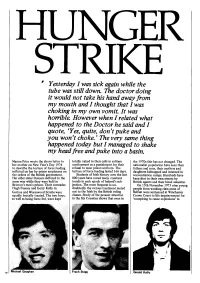

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

The Unsung Heroes of the Irish Peace Process Ted Smyth

REC•NSIDERATI•NS Ted Smyth took part in the Irish peace process as an Irish diplomat in the United States, Britain, and the secretariat of the New Ireland Forum. The Unsung Heroes of the Irish Peace Process Ted Smyth Why did the Irish peace process eventually been viewed as traitors to their Catholic succeed in stopping the sectarian killing af- tribe, but today they are celebrated for their ter centuries of violence in Ireland and when courage and integrity. other sectarian conflicts still rage around the The road to peace in Ireland was led by world? Might there be lessons the Irish many, many individuals who made contri- could teach the world about reconciling bit- butions large and small. There were politi- ter enemies? The political successes in cians who were truly heroic, but it should Northern Ireland owe much to that oft- never be forgotten that the ordinary people scorned ingredient, patient, determined, and of Northern Ireland steadily found their principled diplomacy, which spanned suc- own way toward reconciliation, defying his- cessive administrations in London, Dublin, tory and the climate of fear. Maurice Hayes, and Washington. The result is a structure a columnist for the Irish Independent and a surely durable enough to survive the IRA’s veteran peacemaker puts it well: “Through- disturbing recent violations: an apparently out the troubles, in the darkest days, there long-planned $50 million raid on the have been outstanding examples of charity Northern Bank in Belfast in December at- and courage, of heroic forgiveness, often, tributed to IRA militants and the leader- and most notably, from those who had suf- ship’s unabashedly outlaw offer to shoot fered most. -

Full Book PDF Download

9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page i Irish literature since 1990 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page ii 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page iii Irish literature since 1990 Diverse voices edited by Scott Brewster and Michael Parker Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed in the United States exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page iv Copyright © Manchester University Press 2009 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY- NC-ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. Details of the licence can be viewed at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 978 07190 7563 6 hardback First published 2009 18171615141312111009 10987654321 Typeset by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong 9780719075636_1_pre.qxd 17/2/09 2:11 PM Page v Contents Acknowledgements page vii Notes -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

Urban Planning Approaches in Divided Cities

ITU A|Z • Vol 13 No 1 • March 2016 • 139-156 Urban planning approaches in divided cities Gizem CANER1, Fulin BÖLEN2 1 [email protected] • Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Graduate School of Science, Engineering and Technology, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey 2 [email protected] • Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Architecture, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey Received: April 2014 • Final Acceptance: December 2015 Abstract This paper provides a comparative analysis of planning approaches in divided cities in order to investigate the role of planning in alleviating or exacerbating urban division in these societies. It analyses four urban areas—Berlin, Beirut, Belfast, Jerusalem—either of which has experienced or still experiences extreme divisions related to nationality, ethnicity, religion, and/or culture. Each case study is investigated in terms of planning approaches before division and after reunifi- cation (if applicable). The relation between division and planning is reciprocal: planning effects, and is effected by urban division. Therefore, it is generally assumed that traditional planning approaches are insufficient and that the recognized engagement meth- ods of planners in the planning process are ineffective to overcome the problems posed by divided cities. Theoretically, a variety of urban scholars have proposed different perspectives on this challenge. In analysing the role of planning in di- vided cities, both the role of planners, and planning interventions are evaluated within the light of related literature. The case studies indicate that even though different planning approaches have different consequences on the ground, there is a universal trend in harmony with the rest of the world in reshaping these cities. -

Baku Airport Bristol Hotel, Vienna Corinthia Hotel Budapest Corinthia

Europe Baku Airport Baku Azerbaijan Bristol Hotel, Vienna Vienna Austria Corinthia Hotel Budapest Budapest Hungary Corinthia Nevskij Palace Hotel, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Fairmont Hotel Flame Towers Baku Azerbaijan Four Seasons Hotel Gresham Palace Budapest Hungary Grand Hotel Europe, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Grand Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton DoubleTree Zagreb Zagreb Croatia Hilton Hotel am Stadtpark, Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton Hotel Dusseldorf Dusseldorf Germany Hilton Milan Milan Italy Hotel Danieli Venice Venice Italy Hotel Palazzo Parigi Milan Italy Hotel Vier Jahreszieten Hamburg Hamburg Germany Hyatt Regency Belgrade Belgrade Serbia Hyatt Regenct Cologne Cologne Germany Hyatt Regency Mainz Mainz Germany Intercontinental Hotel Davos Davos Switzerland Kempinski Geneva Geneva Switzerland Marriott Aurora, Moscow Moscow Russia Marriott Courtyard, Pratteln Pratteln Switzerland Park Hyatt, Zurich Zurich Switzerland Radisson Royal Hotel Ukraine, Moscow Moscow Russia Sacher Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Suvretta House Hotel, St Moritz St Moritz Switzerland Vals Kurhotel Vals Switzerland Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam Amsterdam Netherlands France Ascott Arc de Triomphe Paris France Balmoral Paris Paris France Casino de Monte Carlo Monte Carlo Monaco Dolce Fregate Saint-Cyr-sur-mer Saint-Cyr-sur-mer France Duc de Saint-Simon Paris France Four Seasons George V Paris France Fouquets Paris Hotel & Restaurants Paris France Hôtel de Paris Monaco Monaco Hôtel du Palais Biarritz France Hôtel Hermitage Monaco Monaco Monaco Hôtel -

How New Is New Loyalism?

HOW NEW IS NEW LOYALISM? CATHERINE MCGLYNN EUROPEAN STUDIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF SALFORD SALFORD, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, February 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Page 1 Chapter One Hypothesis and Methodology Page 6 Chapter Two Literature Review: Unionism, Loyalism, Page 18 New Loyalism Chapter Three A Civic Loyalism? Page 50 Chapter Four The Roots of New Loyalism 1966-1982 Page 110 Chapter Five New Loyalism and the Peace Process Page 168 Chapter Six New Loyalism and the Progressive Page 205 Unionist Party Chapter Seven Conclusion: How New is New Loyalism? Page 279 Bibliography Page 294 ABBREVIATONS CLMC Combined Loyalist Military Command DENI Department of Education for Northern Ireland DUP Democratic Unionist Party IOO Independent Orange Order IRA Irish Republican Army LAW Loyalist Association of Workers LVF Loyalist Volunteer Force NICRA Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association NIHE Northern Ireland Housing Executive NILP Northern Ireland Labour Party PUP Progressive Unionist Party RHC Red Hand Commandos RHD Red Hand Defenders SDLP Social Democratic and Labour Party UDA Ulster Defence Association UDP Ulster Democratic Party UDLP Ulster Democratic and Loyalist Party UFF Ulster Freedom Fighters UUP Ulster Unionist Party UUUC United Ulster Unionist Council UWC Ulster Workers' Council UVF Ulster Volunteer Force VPP Volunteer Political Party ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my PhD supervisor, Jonathan Tonge for all his support during my time at Salford University. I am also grateful to all the staff at the Northern Irish Political collection at the Linen Hall Library in Belfast for their help and advice. -

La Mon Atrocity Remembered a Memorial Service Has Been Held In

::: u.tv ::: NEWS Body found at Grand Canal SUNDAY Confidential files found at roadside 17/02/2008 18:05:01 Jobs boost for Cork Two 'critical' after attack La Mon atrocity remembered War of words 09:39 A memorial service has been held in Belfast to 09:20 New crime crackdown launched mark the 30th anniversary of the La Mon hotel Atrocity is remembered Man held after 'sex attack' bombing. La Mon atrocity remembered Relatives of the 12 people killed in the 1978 IRA atrocity gathered at Two held after Moira assault Castlereagh Council offices this afternoon for a service of remembrance Three held after drugs find led by the Rev David McIlveen. Limavady fire is 'suspicious' Man dies after Galway crash The DUP`s Irish Robinson and Jimmy Spratt were also among those Brendan Hughes has died attending the service today. Petrol bomb attack in Cullybackey Charge after Belfast death Disruption to Dublin Airport flights The event follows criticism of the DUP from some of the La Mon families who have accused Ian Paisley of letting victims down by going into Cannabis seeds found in Moy government with Sinn Fein. Man dies after Carlow RTC Charges after Portadown attack Two held after drugs seizure More than 400 people were attending a dinner dance in La Mon, when the IRA incendiary device went off. Man stabbed in Sligo Man 'critical' after Dublin assault Bluetongue confirmed in NI A wreath was laid at the La Mon garden in the council grounds today in Donegal murder victim laid to rest memory of the seven women and five men who were killed in one of the worst attacks of the Troubles.