Mormon” in Mormon Studies Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

DIALOGUE PO Box 1094 Farmington, UT 84025 electronic service requested DIALOGUE 52.3 fall 2019 52.3 DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought EDITORS DIALOGUE EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT a journal of mormon thought ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT FICTION Jennifer Quist, Edmonton, Canada POETRY Elizabeth C. Garcia, Atlanta, GA IN THE NEXT ISSUE REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan Papers from the 2019 Mormon Scholars in the INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS Humanities conference: “Ecologies” HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT A sermon by Roger Terry FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT Karen Moloney’s “Singing in Harmony, Stitching in Time” ART Andi Pitcher Davis, Orem, UT BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF Join our DIALOGUE! BUSINESS MANAGER Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT PUBLISHER Jenny Webb, Woodinville, WA Find us on Facebook at Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought COPY EDITORS Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI Follow us on Twitter @DialogueJournal Jared Gillins, Washington DC PRINT SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS EDITORIAL BOARD ONE-TIME DONATION: 1 year (4 issues) $60 | 3 years (12 issues) $180 Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT Becky Reid Linford, Leesburg, VA Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA RECURRING DONATION: Verlyne Christensen, Calgary, AB Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA $10/month Subscriber: Receive four print issues annually and our Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Taylor Petrey, Kalamazoo, MI Subscriber-only digital newsletter Ignacio M. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS --In Memoriam: Leonard J. Arrington, 5 --Remembering Leonard: Memorial Service, 10 --15 February, 1999 --The Voices of Memory, 33 --Documents and Dusty Tomes: The Adventure of Arrington, Esplin, and Young Ronald K. Esplin, 103 --Mormonism's "Happy Warrior": Appreciating Leonard J. Arrington Ronald W.Walker, 113 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --In Search of Ephraim: Traditional Mormon Conceptions of Lineage and Race Armand L. Mauss, 131 TANNER LECTURE • --Extracting Social Scientific Models from Mormon History Rodney Stark, 174 • --Gathering and Election: Israelite Descent and Universalism in Mormon Discourse Arnold H. Green, 195 • --Writing "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (1973): Context and Reflections, 1998 Lester Bush, 229 • --"Do Not Lecture the Brethren": Stewart L. Udall's Pro-Civil Rights Stance, 1967 F. Ross Peterson, 272 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss1/ 1 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY SPRING 1999 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY SPRING 1999 Staff of the Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff Editor: Lavina Fielding Anderson Executive Committee: Lavina Fielding Anderson, Will Bagley, William G. -

Latter-Day Saint Kinship: the Salvific Power of the Family

Latter-Day Saint Kinship: The Salvific Power of the Family Louisa Fowler Honors Defense Date: May 6th, 2020 Thesis Advisor: Professor Christopher Vecsey Defense Committee: Professor Benjamin Stahlberg Professor Steven Kepnes Introduction Since its inception in 1830, the people of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Days have evoked reactions from the public, ranging from confusion to outrage. In turn, the Church community has struggled to fit into secular society. The Church has constantly worked to craft and improve its relationship with the world. Recently, in 2018, Latter-Day Saint President Russell M. Nelson explained that the “Lord has impressed upon [his] mind the importance of the name he has revealed for the Church.”1 Latter-Day Saints reject the title ‘Mormons,’ asking outsiders to refer to members of the Church as Latter-Day Saints. Non-members of the Church misunderstand the Latter-Day Saint community, right down to its name. For the last two centuries, the Church community has been mysterious and confusing to the ‘outside world.’ What exactly do the Latter-Day Saints believe? Why do they behave the way that they do? Why do they seem so ‘other’, in relation to the greater society in which they live? This thesis will utilize the lens of the Latter-Day social structure-- from family life to marital expectations, to dating guidelines-- in order to demonstrate that this religion is unique due to its view of the family as sacred. An understanding of Latter-Day Saints’ family life is the key to understanding their Church because Latter-Day Saint religion is deeply relational, embedded in gender, marriage, and the family. -

Policing the Borders of Identity At

POLICING THE BORDERS OF IDENTITY AT THE MORMON MIRACLE PAGEANT Kent R. Bean A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2005 Jack Santino, Advisor Richard C. Gebhardt, Graduate Faculty Representative John Warren Nathan Richardson William A. Wilson ii ABSTRACT Jack Santino, Advisor While Mormons were once the “black sheep” of Christianity, engaging in communal economic arrangements, polygamy, and other practices, they have, since the turn of the twentieth century, modernized, Americanized, and “Christianized.” While many of their doctrines still cause mainstream Christians to deny them entrance into the Christian fold, Mormons’ performance of Christianity marks them as not only Christian, but as perhaps the best Christians. At the annual Mormon Miracle Pageant in Manti, Utah, held to celebrate the origins of the Mormon founding, Evangelical counter- Mormons gather to distribute literature and attempt to dissuade pageant-goers from their Mormonism. The hugeness of the pageant and the smallness of the town displace Christianity as de facto center and make Mormonism the central religion. Cast to the periphery, counter-Mormons must attempt to reassert the centrality of Christianity. Counter-Mormons and Mormons also wrangle over control of terms. These “turf wars” over issues of doctrine are much more about power than doctrinal “purity”: who gets to authoritatively speak for Mormonism. Meanwhile, as Mormonism moves Christianward, this creates room for Mormon fundamentalism, as small groups of dissidents lay claim to Joseph Smith’s “original” Mormonism. Manti is home of the True and Living Church of Jesus Christ of Saints of the Last Days, a group that broke away from the Mormon Church in 1994 and considers the mainstream church apostate, offering a challenge to its dominance in this time and place. -

Armand L. Mauss, Shifting Borders and a Tattered Passport: Intellectual Journeys of a Mormon Academic Reviewed by David E

Mormon Studies Review Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 25 1-1-2014 Armand L. Mauss, Shifting Borders and a Tattered Passport: Intellectual Journeys of a Mormon Academic Reviewed by David E. Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Campbell, Reviewed by David E. (2014) "Armand L. Mauss, Shifting Borders and a Tattered Passport: Intellectual Journeys of a Mormon Academic," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 25. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol1/iss1/25 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Campbell: Armand L. Mauss, <em>Shifting Borders and a Tattered Passport: In 214 Mormon Studies Review the Name of Hawaiians.2 One aspect of the story that Kester was not able to tell, yet one that does not diminish the overall significance of this book, is the impact of Mormon settlement on the indigenous nations in what is now Utah. For additional reading on this topic, I recommend Ned Blackhawk’s Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West.3 Dr. Hokulani K. Aikau is associate professor of Native Hawaiian and In- digenous politics in the Department of Political Science at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She is the author of A Chosen People, a Promised Land: Mormonism and Race in Hawai‘i (University of Minnesota Press, 2012). -

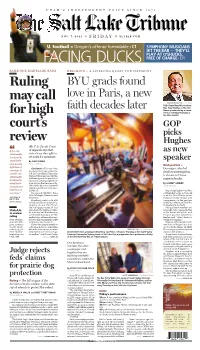

Peggy Fletcher Stack, the Salt Lake Tribune

UTAH’S INDEPENDENT VOICE SINCE 1871 NOV. 7, 2014 « FRIDAY » SLTRIB.COM U. football • Oregon’s offense formidable > C1 SYMPHONY MUSICIANS HIT THE BAR — THEY’LL PLAY AT O’SHUCKS, FACING DUCKS FREE OF CHARGE > D1 SAME-SEX MARRIAGE BANS RELIGION • A LIFELONG QUEST FOR HARMONY Ruling BYU grads found may call love in Paris, a new FRANCISCO KJOLSETH | The Tribune Utah House Republicans chose faith decades later Rep. Greg Hughes as the new House speaker during a closed for high election meeting Thursday at the state Capitol. court’s GOP picks review Hughes “ 6th U.S. Circuit Court If it is con- of Appeals says that as new stitutionally states have the right to irrational to set rules for marriage. speaker stand by the By DAN SEWELL man-woman The Associated Press Utah politics • definition of Cincinnati • The march to- Dunnigan, who led marriage, it ward gay marriage across the Swallow investigation, U.S. hit a roadblock Thursday must be con- is chosen as House stitutionally when afederalappeals courtup- held laws againstthepractice in majority leader. irrational to four states, creating asplitin the stand by the legal system that increases the By ROBERT GEHRKE monogamous chancestheSupremeCourtwill The Salt Lake Tribune step in to decide the issue once definition of and for all. Rep. Greg Hughes was elect- marriage.” The cases decided were from ed Thursday as the new speak- Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky and er of the Utah House, prom- JEFFREY Tennessee. ising to bring energy and SUTTON Breaking ranks with oth- transparency to the position 6th Circuit judge er federal courts around the and to be inclusive of all of the country, the 6th U.S. -

Chapter 14 Latter-Day Saints and the Problem of Theology Fenella

Chapter 14 Latter-Day Saints and the Problem of Theology Fenella Cannell “‘I’ll freely admit that I’m not a theologian.’ Bishop Hammond said.” In April 2014, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) excommunicated one of its rank and file members, a woman named Kate Kelly. Kelly was declared apostate for advocating for her church’s recognition of women as members of the lay priesthood, which is currently reserved to adult men. In October 2013, representatives of the LDS group Ordain Women, to which Kelly belonged, made news in Utah and other Mormon stronghold states by requesting tickets to attend the ‘priesthood sessions,’ - that is, men-only sessions,- of the semi-annual cConference of the LDS church. These are held in the Conference Centre Center in Salt Lake City, but are livestreamed streamed live to various satellite locations where ‘priesthood holders’ ( that is, i.e., men) are invited and expected to go to watch them collectively. Footage posted online that year and the following year showed examples of what happened in some locations. For instance, Brigham Young University (BYU) graduate Abbey Hansen and others gained entrance to watch the broadcasts with the men at BYU’s Marriott Centre Center in October, 2015. The video shows a very Mormon encounter, in which polite and modestly -dressed members of Ordain Women awkwardly ask to be allowed to enter the meeting, and are eventually, though very reluctantly, admitted by an equally polite and respectably -dressed lady on at the door ( Karen Roberts). The encounter takes -

Mormon Feminism: Not an Oxymormon Alexa Himonas [email protected]

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2015 Mormon Feminism: Not an Oxymormon Alexa Himonas [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Himonas, Alexa, "Mormon Feminism: Not an Oxymormon" (2015). Summer Research. Paper 246. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/246 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mormon Feminism: Not an Oxymormon Alexa Himonas September 23, 2015 Advisor: Greta Austin Himonas 1 Acknowledgments Thank you first and foremost to all of my grandparents, without whose hard work, sacrifice, love and vast support I would not be able to be studying my passion. Thank you to my Nana and Yiayia for being incredible examples of people I would love to become. Professor Greta Austin, my advisor for this project, gave me brilliant guidance and support, and was the perfect advisor for this project. I feel very lucky I got to work with her. My parents and sister listened to me endlessly monologue about all that I was learning this summer. Both my parents were incredibly helpful in this entire process, from reading my research proposal to helping me with my research presentation. My mother especially deserves recognition for spending hours on poster design and setup with me. It would be impossible for me to feel any more supported. -

The Story of Mormons for the Equal Rights Amendment

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2018 From Housewives to Protesters: The Story of Mormons for the Equal Rights Amendment Kelli N. Morrill Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Morrill, Kelli N., "From Housewives to Protesters: The Story of Mormons for the Equal Rights Amendment" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7056. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7056 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM HOUSEWIVES TO PROTESTERS: THE STORY OF MORMONS FOR THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT by Kelli N. Morrill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: _____________________ ____________________ Victoria Grieve, Ph.D. Rebecca Anderson, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member _____________________ ____________________ Daniel Davis, M.A. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Kelli N. Morrill 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FROM HOUSEWIVES TO PROTESTERS: THE STORY OF MORMONS FOR THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT by Kelli N. Morrill, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Dr. Victoria Grieve Department: History In the mid 1970s a group of highly educated, white Mormon women living in Virginia formed the group Mormons for the ERA (MERA). -

From the God Makers to the Myth Maker: Simultaneous— and Lasting—Challenges to Mormonism’S Reputation in the 1980S

Haws: Challenges to Mormonism’s Reputation in the 1980s 31 From The God Makers to the Myth Maker: Simultaneous— and Lasting—Challenges to Mormonism’s Reputation in the 1980s J. B. Haws What a difference two decades can make. In 1973, on the heels of the presidency of David O. McKay, a time retired LDS Public Affairs managing director Bruce Olsen called the “golden era of Mormonism,” the Church commissioned an opinion survey.1 Respondents to that survey ranked the LDS Church relatively low in comparison to other de- nominations when it came to perceptions of secrecy and suspicion, and even lower in terms of public influence. In line with those survey results, in 1981 Martin Marty, one of the country’s most eminent historians of religion, wrote that “by 1980, the Mormons had grown to be so much like everyone else or, perhaps, had so successfully gotten other Americans to be like them, that they no longer inspired curiosity for wayward ways.”2 In retrospect, there is significant irony in that pronouncement. Marty could hardly have guessed the extent to which curiosity, consternation, and even contempt for the wayward ways of Mormonism would experience a re- birth after 1980 and spawn what LDS Apostle Dallin H. Oaks called “some of J. B. Haw S ([email protected]) received a BA from Weber State University, an MA from Brigham Young University, and a PhD in American History from the University of Utah. He recently accepted an appointment as an assistant professor of Church History and Doc- trine at Brigham Young University. -

An Overview of LDS Involvement in the Proposition 8 Campaign

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 26 Issue 3 Volume 26, Spring 2012, Issue 3 Article 8 "The Divine Institution of Marriage": An Overview of LDS Involvement in the Proposition 8 Campaign Kaimipono David Wenger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THE DIVINE INSTITUTION OF MARRIAGE": AN OVERVIEW OF LDS INVOLVEMENT IN THE PROPOSITION 8 CAMPAIGN KAIMIPONO DAVID WENGER1 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon church) was heavily involved in the passage ofProposition8 in California. Church members participated in a variety of ways including extensive fundraisingand a variety of publicity efforts such as door-to-door get-out- the-word campaigns. Statements by the church and its leaders were a central part of the LDS Proposition 8 strategy. The church issued three official statements on Proposition 8, which combined theological and religious content with specific political, sociological, and legal claims. For instance, in their support for Proposition 8, LDS church leaders (most of them not legal professionals) made a series of detailed predictions about the legal consequences of same-sex marriage. These official declarations were supplemented and reinforced by a variety of unofficial statements from church leaders and members. This Article tells the story of LDS involvement with Proposition 8, in particular the legal claims made by the church and its leaders.