Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Chapter (PDF)

CONTENTS Introduction by Fawn Μ. Brodie Note on the Text ROUTE FROM LIVERPOOL το GREAT SALT LAKE VALLEY Preface [Chapters I-IX by Linforth] Chapter I. Commencement of the Latter-day Saints' Emigration—History until the Suspension in 1846 Chapter II. Memorial to the Queen—Re-opening of the Emigration—History until 1851 Chapter III. History of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund—Act of Incorporation by the General Assembly of Deseret Chapter IV. History of the Emigration from 1851 to 1852—Contemplated Routes via the Isthmus of Panama and Cape Horn Chapter V. History of the Emigration from 1852 to April, 1854—Extensive Operations of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company vi CONTENTS Chapter VI. Foreign Emigration passing through Liverpool 38 Chapter VII. Statistics of the Latter-day Saints' Emigration from the British Isles 40 Chapter VIII. Mode of conducting the Emigration 49 Chapter IX. Instructions to Emigrants 54 [Chapters X-XXI by Piercy] Chapter X. Departure from Liverpool—San Domingo—Cuba—The Gulf of Mexico—The Mississippi River—The Balize—Arrival at New Orleans—Attempts of "Sharpers" to board the Ship and pilfer from the Emigrants 62 Chapter XI. Louisiana—The City of New Orleans—Disembarkation 71 Chapter XII. Departure from New Orleans—Steam-Boats—Negro-Slavery— Carrollton—The Face of the Country—-Baton Rouge—Red River —Mississippi—Unwholesomeness of the waters of the Mississippi —Danger in procuring Water from the Stream—Washing away of the Banks of the River—Snags—Landing at Natchez at night —Beautiful effect caused by reflection on the Water of the Light from the Steamboat Windows—^American Taverns and Hospi- tality—Rapidity at Meals—American Cooking Stoves and Wash- ing Boards—Old Fort Rosalie—An Amateur Artist 73 Chapter XIII. -

INTERPRETER§ a Journal of Mormon Scripture

INTERPRETER§ A Journal of Mormon Scripture Volume 21 • 2016 The Interpreter Foundation Orem, Utah The Interpreter Foundation Chairman and President Contributing Editors Daniel C. Peterson Robert S. Boylan John M. Butler Vice Presidents James E. Faulconer Jeffrey M. Bradshaw Kristine Wardle Frederickson Daniel Oswald Benjamin I. Huff Allen Wyatt Jennifer C. Lane David J. Larsen Executive Board Donald W. Parry Kevin Christensen Ugo A. Perego Steven T. Densley, Jr. Stephen D. Ricks Brant A. Gardner William J. Hamblin G. Bruce Schaalje Jeff Lindsay Andrew C. Smith Louis C. Midgley John A. Tvedtnes George L. Mitton Sidney B. Unrau Gregory L. Smith Stephen T. Whitlock Tanya Spackman Lynne Hilton Wilson Ted Vaggalis Mark Alan Wright Board of Editors Donor Relations Matthew L. Bowen Jann E. Campbell David M. Calabro Alison V. P. Coutts Treasurer Craig L. Foster Kent Flack Taylor Halverson Ralph C. Hancock Production Editor & Designers Cassandra S. Hedelius Kelsey Fairbanks Avery Benjamin L. McGuire Tyler R. Moulton Timothy Guymon Mike Parker Bryce M. Haymond Martin S. Tanner Bryan J. Thomas Gordon C. Thomasson A. Keith Thompson John S. Thompson Bruce F. Webster The Interpreter Foundation Editorial Consultants Media & Technology Talia A. K. Abbott Sean Canny † Linda Hunter Adams Scott Dunaway Merrie Kay Ames Richard Flygare Jill Bartholomew Brad Haymond Tyson Briggs Tyler R. Moulton Starla Butler Tom Pittman Joshua Chandler Russell D. Richins Kasen Christensen S. Hales Swift Ryan Daley Victor Worth Marcia Gibbs Jolie Griffin Laura Hales Hannah Morgan Jordan Nate Eric Naylor Don Norton Neal Rappleye Jared Riddick William Shryver Stephen Owen Smoot Kaitlin Cooper Swift Jennifer Tonks Austin Tracy Kyle Tuttle Scott Wilkins © 2016 The Interpreter Foundation. -

The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.•Łs Â

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Student Writing Award Winners Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 12-2013 Leveraging Doubt: The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.‟s “Mormonism‟s Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview” on Mormon Thought Chad L. Nielsen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_stwriting Recommended Citation Nielsen, Chad L., "Leveraging Doubt: The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.'s "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview"" (2013). Arrington Student Writing Award Winners. This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Student Writing Award Winners by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leveraging Doubt Leveraging Doubt: The Impact of Lester E. Bush, Jr.‟s “Mormonism‟s Negro Doctrine: A Historical Overview” on Mormon Thought Chad L. Nielsen Utah State University 1 Leveraging Doubt The most exciting single event of the years I [Leonard J. Arrington] was church historian occurred on June 9, 1978, when the First Presidency announced a divine revelation that all worthy males might be granted the priesthood…. Just before noon my secretary, Nedra Yeates Pace, telephoned with remarkable news: Spencer W. Kimball had just announced a revelation that all worthy males, including those of African descent, might be ordained to the priesthood. Within five minutes, my son Carle Wayne telephoned from New York City to say he had heard the news. I was in the midst of sobbing with gratitude for this answer to our prayers and could hardly speak with him. -

Idaho Profile Idaho Facts

Idaho Profile Idaho Facts Name: Originally suggested for Colorado, the name “Idaho” was used for a steamship which traveled the Columbia River. With the discovery of gold on the Clearwater River in 1860, the diggings began to be called the Idaho mines. “Idaho” is a coined or invented word, and is not a derivation of an Indian phrase “E Dah Hoe (How)” supposedly meaning “gem of the mountains.” Nickname: The “Gem State” Motto: “Esto Perpetua” (Let it be perpetual) Discovered By Europeans: 1805, the last of the 50 states to be sighted Organized as Territory: March 4, 1863, act signed by President Lincoln Entered Union: July 3, 1890, 43rd state to join the Union Official State Language: English Geography Total Area: 83,569 square miles – 14th in area size (read more) Water Area: 926 square miles Highest Elevation: 12,662 feet above sea level at the summit of Mt. Borah, Custer County in the Lost River Range Lowest Elevation: 770 feet above sea level at the Snake River at Lewiston Length: 164/479 miles at shortest/longest point Width: Geographic 45/305 miles at narrowest/widest point Center: Number of settlement of Custer on the Yankee Fork River, Custer County Lakes: Navigable more than 2,000 Rivers: Largest Snake, Coeur d’Alene, St. Joe, St. Maries and Kootenai Lake: Lake Pend Oreille, 180 square miles Temperature Extremes: highest, 118° at Orofino July 28, 1934; lowest, -60° at Island Park Dam, January 18, 1943 2010 Population: 1,567,582 (US Census Bureau) Official State Holidays New Year’s Day January 1 Martin Luther King, Jr.-Human Rights Day Third Monday in January Presidents Day Third Monday in February Memorial Day Last Monday in May Independence Day July 4 Labor Day First Monday in September Columbus Day Second Monday in October Veterans Day November 11 Thanksgiving Day Fourth Thursday in November Christmas December 25 Every day appointed by the President of the United States, or by the governor of this state, for a public fast, thanksgiving, or holiday. -

Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848-1861 / Dunvood Ball

Amy Regulars on the WestmFrontieq r 848-1 861 This page intentionally left blank Army Regulars on the Western Frontier DURWOOD BALL University of Oklahoma Press :Norman Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ball, Dunvood, 1960- Army regulars on the western frontier, 1848-1861 / Dunvood Ball. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8061-3312-0 I. West (U.S.)-History, Military-I 9th century. 2. United States. Army-History- 19th century. 3. United States-Military policy-19th century. 4. Frontier and pioneer life-West (U.S.) 5. West (US.)-Race relations. 6. Indians of North Arnerica- Government relations-1789-1869. 7. Indians of North America-West (U.S.)- History-19th century. 8. Civil-military relations-West (U.S.)-History-19th century. 9. Violence-West (U.S.)-History-I 9th century. I. Title. F593 .B18 2001 3 5~'.00978'09034-dcz I 00-047669 CIP The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources, Inc. m Copyright O 2001 by the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Publishing Division of the University. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the U.S.A. 12345678910 For Mom, Dad, and Kristina This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Maps IX Preface XI Acknowledgments xv INT R o D U C T I o N : Organize, Deploy, and Multiply XIX Prologue 3 PART I. DEFENSE, WAR, AND POLITICS I Ambivalent Duty: Soldiers, Indians, and Frontiersmen I 3 2 All Front, No Rear: Soldiers, Desert, and War 24 3 Chastise Them: Campaigns, Combat, and Killing 3 8 4 Internal Fissures: Soldiers, Politics, and Sectionalism 56 PART 11. -

Moderating the Mormon Discourse on Modesty

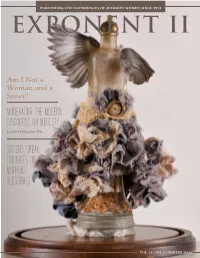

PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF MORMON WOMEN SINCE 1974 EXPONENT II Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? MODERATING THE MODERN DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Jennifer Finlayson-Fife SISTERS SPEAK: THOUGHTS ON MOTHERS’ BLESSINGS VOL. 33 | NO. 3 | WINTER 2014 04 PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF 18 Mormon Women SINCE 1974 14 16 WHAT IS EXPONENT II ? The purpose of Exponent II is to provide a forum for Mormon women to share their life 34 experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and our commitment to 24 women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity 30 of women. 36 FEATURED STORIES ADDITIONAL FEATURES 03 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 24 FLANNEL BOARD New Recruits in the Armies of Shelaman: Notes from a Primary Man MODERATING THE 04 AWAKENINGS Rob McFarland Making Peace with Mystery: To Prophet Jonah MORMON DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Mary B. Johnston 28 Reflections on a Wedding BY JENNIFER FINLAYSON-FIFE, WILMETTE, ILLINOIS Averyl Dietering 07 SISTERS SPEAK ON THE COVER: I believe the LDS cultural discourse around modesty is important because Sharing Experiences with Mothers’ Blessings 30 SABBATH PASTORALS Page Turner of its very real implications for women in the Church. How we construct Being Grateful for God’s Hand in a World I our sexuality deeply affects how we relate to ourselves and to one another. Moderating the Mormon Discourse on -

Essays on the Persecution of Religious Minorities by David Thomas Smith

Essays on the Persecution of Religious Minorities by David Thomas Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor William R. Clark, co-chair Professor Anna M. Grzymala-Busse, co-chair Professor Robert J. Franzese, Jr. Professor Andrei S. Markovits Professor Robert W. Mickey i Acknowledgements Throughout the last six and a half years I have benefited enormously from the mentorship and friendship of my wonderful dissertation committee members: Bill Clark, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Andy Markovits, Rob Mickey and Rob Franzese. I assembled this committee before I even knew what I wanted to write about, and I made the right choices—I cannot imagine a more supportive, patient and insightful group of advisers. They gave me badly-needed discipline when I needed it (which was all the time) and oversaw numerous episodes of Schumpeterian “creative destruction.” They also gave me more ideas than I could ever hope to assimilate, ideas which will be providing me with directions for future research for many years to come. But these huge contributions are minor in comparison to the fact that they taught me how to think like a political scientist. I couldn’t ask for anything more. All of these papers had trial runs in various internal workshops and seminars at the University of Michigan, and I profited greatly from the structured feedback that I received from the Michigan political science community, faculty and grad students alike. Thanks to everyone who was a discussant for one of these papers—Zvi Gitelman, Chuck Shipan, Sana Jaffrey, Cassie Grafstrom (twice!), Ron Inglehart, Ken Kollman, Allison Dale, Pam Brandwein, Andrea Jones-Rooy, Rob Salmond and Jenna Bednar. -

William Smith, Isaach Sheen, and the Melchisedek & Aaronic Herald

William Smith, Isaach Sheen, and the Melchisedek & Aaronic Herald by Connell O'Donovan William Smith (1811-1893), the youngest brother of Mormon prophet, Joseph Smith, was formally excommunicated in absentia from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on October 19, 1845.1 The charges brought against him as one of the twelve apostles and Patriarch to the church, which led to his excommunication and loss of position in the church founded by his brother, included his claiming the “right to have one-twelfth part of the tithing set off to him, to be appropriated to his own individual use,” for “publishing false and slanderous statements concerning the Church” (and in particular, Brigham Young, along with the rest of the Twelve), “and for a general looseness and recklessness of character which is ill comported with the dignity of his high calling.”2 Over the next 15 years, William founded some seven schismatic LDS churches, as well as joined the Strangite LDS Church and even was surreptitiously rebaptized into the Utah LDS church in 1860.3 What led William to believe he had the right, as an apostle and Patriarch to the Church, to succeed his brother Joseph, claiming authority to preside over the Quorum of the Twelve, and indeed the whole church? The answer proves to be incredibly, voluminously complex. In the research for my forthcoming book, tentatively titled Strange Fire: William Smith, Spiritual Wifery, and the Mormon “Clerical Delinquency” Crises of the 1840s, I theorize that William may have begun setting up his own church in the eastern states (far from his brother’s oversight) as early as 1842. -

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects by Eugene England

Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects By Eugene England This essay is the culmination of several attempts England made throughout his life to assess the state of Mormon literature and letters. The version below, a slightly revised and updated version of the one that appeared in David J. Whittaker, ed., Mormon Americana: A Guide to Sources and Collections in the United States (Provo, Utah: BYU Studies, 1995), 455–505, is the one that appeared in the tribute issue Irreantum published following England’s death. Originally published in: Irreantum 3, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 67–93. This, the single most comprehensive essay on the history and theory of Mormon literature, first appeared in 1982 and has been republished and expanded several times in keeping up with developments in Mormon letters and Eugene England’s own thinking. Anyone seriously interested in LDS literature could not do better than to use this visionary and bibliographic essay as their curriculum. 1 ExpEctations MorMonisM hAs bEEn called a “new religious tradition,” in some respects as different from traditional Christianity as the religion of Jesus was from traditional Judaism. 2 its beginnings in appearances by God, Jesus Christ, and ancient prophets to Joseph smith and in the recovery of lost scriptures and the revelation of new ones; its dramatic history of persecution, a literal exodus to a promised land, and the build - ing of an impressive “empire” in the Great basin desert—all this has combined to make Mormons in some ways an ethnic people as well as a religious community. Mormon faith is grounded in literal theophanies, concrete historical experience, and tangible artifacts (including the book of Mormon, the irrigated fields of the Wasatch Front, and the great stone pioneer temples of Utah) in certain ways that make Mormons more like ancient Jews and early Christians and Muslims than, say, baptists or Lutherans. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley. -

In Union Is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1998 In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900 Kathleen C. Haggard Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Haggard, Kathleen C., "In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900" (1998). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 738. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/738 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. " IN UNION IS STRENGTH" MORMON WOMEN AND COOPERATION, 1867-1900 by Kathleen C. Haggard A Plan B thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1998 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Anne Butler, for never giving up on me. She not only encouraged me, but helped me believe that this paper could and would be written. Thanks to all the many librarians and archival assistants who helped me with my research, and to Melissa and Tige, who would not let me quit. I am particularly grateful to my parents, Wayne and Adele Creager, and other family members for their moral and financial support which made it possible for me to complete this program. Finally, I express my love and gratitude to my husband John, and our children, Lindsay and Mark, for standing by me when it meant that I was not around nearly as much as they would have liked, and recognizing that, in the end, the late nights and excessive typing would really be worth it. -

Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J

Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 Number 1 Article 7 1-1-2017 Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, eds., The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women's History Reviewed by Dave Hall, Susanna Morrill, Catherine A. Brekus [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Catherine A. Brekus, Reviewed by Dave Hall, Susanna Morrill, (2017) "Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, eds., The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women's History," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol4/iss1/7 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Catherine A. Brekus: Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matth Review Panel Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, eds. The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History. Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016. Reviewed by Dave Hall, Susanna Morrill, and Catherine A. Brekus DAVE HALL: This work gathers in one useful volume documents piv- otal to understanding the early history of Mormon women. Adding to its value is the wealth of knowledge contributed by its editorial team, headed by experienced scholars Jill Derr, Carol Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew Grow.