Mormon Literature: Progress and Prospects by Eugene England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Mormon Stories

EUGENE ENGLAND ed bright angels and familiars contemporary mormon stories salt lake city signature books 1992 xx 548348 appp 199519.95 reviewed by patricia mann alto a high school english teacher in ukiahukich california academics have recently been inundated with demands to include in what has been called a eurocentricEurocentric canon more litera- ture from other cultures such inclusion would necessitate exclu- sion of some standard material to make room in crowded curriculums yet the multiculturalists contend that students derive great satisfaction in literature written by or relating to their own cultures after reading bright angels and familiars contemporary mormon stories I1 better understand the deep satiety that comes from seeing ones culture explained explored and enhanced in what would be in anyones book good literature fortunately or not this books inclusion in the mormon canon of literature would not precipitate bumping much material off the short listfistbist of what one should read cormonsmormons are just now coming into their own in the realm of good literature england explores this coming of age in his introductory essay the new mormon fiction which stands as one of the best parts of the book he has peeled back the academic verbiage and schol- arly pretension that often accompany such an undertaking and offers a lucid and concise history and explanation of mormon fiction after tracing mormon literature from early apology and satire through home literature and the lost generation he intro- duces the crop of well schooled -

Taking Mormons Seriously: Ethics of Representing Latter-Day Saints in American Fiction

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-07-10 Taking Mormons Seriously: Ethics of Representing Latter-day Saints in American Fiction Terrol Roark Williams Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Williams, Terrol Roark, "Taking Mormons Seriously: Ethics of Representing Latter-day Saints in American Fiction" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 1159. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1159 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TAKING MORMONS SERIOUSLY: ETHICS OF REPRESENTING LATTER-DAY SAINTS IN AMERICAN FICTION by Terrol R. Williams A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Brigham Young University August 2007 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Terrol R. Williams This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. Date Gideon O. Burton, Chair Date Susan Elizabeth Howe, Reader Date Phillip A. Snyder, Reader Date Frank Q. Christianson, Graduate Advisor Date Nicholas Mason, Associate Chair -

Healing and Making Peace—In the World and in The

Healing and Making Peace—In the World and the Church By Eugene England This essay examines the ways that feelings of being unjustly treated can lead us into terribly destructive cycles of revenge, and England then uses scripture and stories from history and Shakespeare to suggest that the only way to heal such rifts is through proactively following Christ’s gospel and its emphasis on offering genuine mercy . Originally published : Sunstone 15, no. 6 (December 1991): 36–46. N THE FALL of 1955, Charlotte and I were living in Mapusaga, a small village I in American Samoa. We had been married two years and had been missionaries to the Polynesians for a year and a half. Charlotte was five months pregnant. We were teaching a woman named Taligu E’e, who had Mormon relatives and who had agreed to meet us each Wednesday afternoon. We would walk to her fale , her circu - lar, open, thatch-roofed home, and teach her in broken Samoan one of the lessons from the systematic missionary teaching guide. She would listen politely and impassively, her eyes looking down at the mats we sat on, and after we finished would serve us the meal she had prepared. One Wednesday we taught her the plan of salvation. We told her how we had all chosen to come to earth, with Christ, who had offered himself as our Savior, and how important it was to follow him if we knew him. Then I told her how, by doing temple work, we could help those who had died without knowing Christ, but who were being taught about him in the spirit world. -

EE Published

Becoming a World Religion: Blacks, the Poor—All of Us By Eugene England This essay, originally given as a talk at the 1998 Sunstone West Symposium held in Los Angeles, California, illustrates the ways that Mormons continue to be both racist and classist, and argues that for people to learn to accept the unconditional love God has for us as manifest through the Atonement, we must truly become, like God, “no respecter of persons.” Originally published : Sunstone 21, no. 2 (June-July 1998): 49–60. ROM THE VERY earliest days in the 1830s, of what they called “the Restora - F tion,” the leaders of a tiny American sect known as Mormonism, though reviled and persecuted and driven, have constantly repeated the astounding claim that their church would not only succeed but would grow into a world religion—in fact, the world religion. In 1831, the Lord announced through Joseph Smith that “the keys of the kingdom of God are committed unto man on the earth, and from thence shall the gospel roll forth unto the ends of the earth, as the stone that is cut out of the mountain without hands shall roll forth, until it has filled the whole earth” (D&C 65:2). Since then, we Latter-day Saints have thought ourselves to be the chosen ones to fulfill that prophecy made first in Daniel’s interpretation of the dream of Nebuchadnezzar. He saw, you remember, a great composite figure representing the kingdoms of the world, from the head of gold to feet and toes of clay, that was smitten by a stone which then “became a great mountain, and filled the whole earth” (Dan. -

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Contributors

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 13 Number 1 Article 1 7-31-2004 Contributors Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Studies, Journal of Book of Mormon (2004) "Contributors," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 13 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol13/iss1/1 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CONTRIBUTORS Gerald S. Argetsinger is an associate professor in the Department of Cultural and Creative Studies at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf, a college of the Rochester Institute of Technology. He received a BA in theatre from Brigham Young University and a PhD in dramaturgy from Bowling Green State University. He has 25 years’ experience in directing outdoor drama, and his scholarly writings include two books on the father Gerald S. Argetsinger of Danish theatre, Ludvig Holberg. David F. Boone is associate professor of church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University. His research interests include the frontier American West, the historical Southern States Mission, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the 20th century. David F. Boone John E. Clark is professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University and director of the BYU New World Archaeological Foundation. John E. -

Mormondom's Lost Generation: the Novelists of the 1940S

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 7 1-1-1978 Mormondom's Lost Generation: The Novelists of the 1940s Edward A. Geary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Geary, Edward A. (1978) "Mormondom's Lost Generation: The Novelists of the 1940s," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol18/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Geary: Mormondom's Lost Generation: The Novelists of the 1940s mormondomsMormondoms lost generation the novelists of the 1940s edward A geary wallace stegner in his essay on the writer in the american west laments that westerners have been unable to get beyond the celebration of the heroic and mythic frontier he says we cannot find apparently a present andanclanci living society that is truly ours and that contains the material of a deep commit- ment instead we must live in exile and write of anguishesanguislanguisheshes not our own or content ourselves with the bland troubles the remembered vioviolenceslences the already endured hardships of a regional success story without an aftermath 1L but perhaps this tendency is characteristic of regional literature in general not just of western regional literature faulkner has his heroic -

Mormon Novels Entertain While Teaching Lessons

SUNSTONE BOOKS MORMON NOVELS ENTERTAIN WHILE TEACHING LESSONS by Peggy Fletcher Stack Tribune religion writer This story orignally appeared in the 10 October 1998 Salt Lake Tribune. Reprinted in its entirety by permission. The world of romance novels seethes with heaving bosoms, manly men, seduction, betrayal. Mormon novels have all of that and then some-excommunica- tion, repentance, prayer, re- demution. In the past few years, popular Today's wxnovels deal with serious topics-abuse, adultery, date rape- fiction-romance, mystery and but they have Mormon theology-based solutions. historical novels-aimed at members of The Church of Jesus Too, such books are peopled they are getting something out of Since then, Weyland, a Christ of Latter-day Saints has with recognizable LDS charac- it." physics professor at LDS-owned been selling by the barrelful. ters-Brigham Young University 100 Years: The first Mormon Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho, Anita Stansfield has sold more students, missionaries, converts, popular novel may have been has written a dozen more, many than two hundred thousand bishops, Relief Society presi- Added Upon, written by Nephi of them almost as successful. copies of her work. Jack Weyland dents, religion professors, home Anderson in 1898, Cracroft says. "The ones that have done the routinely sells between twenty schoolers. It told the story of an LDS best are all issue-related," says and thirty thousand novels And they are laced with theo- I couple who met in a pre-Earth Emily Watts, an associate editor aimed at the LDS teen market. logcal certainty existence and agreed to get to- at Deseret Book who has worked The hbrk and the Glory, a "Lots of Mormons feel they gether in mortal life. -

Sacred Sci-Fi Orson Scott Card As Mormon Mythmaker

52-59_smith_card:a_chandler_kafka 2/13/2011 8:57 pm page 52 SUNSTONE I, Ender, being born of goodly parents . SACRED SCI-FI ORSON SCOTT CARD AS MORMON MYTHMAKER By Christopher C. Smith LMOST EVERY CULTURE HAS TRADITIONAL new myths are less vulnerable than the old mythologies be - mythologie s— usually stories set in a primordial cause they make no claim to be literally, historically true. A time of gods and heroes. Although in popular dis - Their claim to truth is at a deeper, more visceral level. course the term “myth” typically refers only to fiction, lit - Fantasy and science fiction can be used either to chal - erary critics and theologians use it to refer to any “existen - lenge and replace or to support and complement traditional tial” stor y— even a historical one. Myths explain how the religious mythologies. One author who has adopted the world came to be, why it is the way it is, and toward what latter strategy is Mormon novelist Orson Scott Card. end it is headed. They explore the meaning of life and pro - Literary critic Marek Oziewicz has found in Card’s fiction all vide role models for people to imitate. They express deep the earmarks of a modern mythology. It has universal scope, psychological archetypes and instill a sense of wonder. In creates continuity between past, present, and future, inte - short, they answer the Big Questions of life and teach us grates emotion and morality with technology, and posits the how to live. interrelatedness of all existence. 2 Indeed, few science fiction Due to modernization in recent centuries, the world has and fantasy authors’ narratives feel as mythic as Card’s. -

Moderating the Mormon Discourse on Modesty

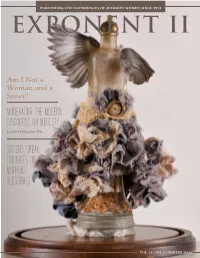

PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF MORMON WOMEN SINCE 1974 EXPONENT II Am I Not a Woman and a Sister? MODERATING THE MODERN DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Jennifer Finlayson-Fife SISTERS SPEAK: THOUGHTS ON MOTHERS’ BLESSINGS VOL. 33 | NO. 3 | WINTER 2014 04 PUBLISHING THE EXPERIENCES OF 18 Mormon Women SINCE 1974 14 16 WHAT IS EXPONENT II ? The purpose of Exponent II is to provide a forum for Mormon women to share their life 34 experiences in an atmosphere of trust and acceptance. This exchange allows us to better understand each other and shape the direction of our lives. Our common bond is our connection to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and our commitment to 24 women. We publish this paper as a living history in celebration of the strength and diversity 30 of women. 36 FEATURED STORIES ADDITIONAL FEATURES 03 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 24 FLANNEL BOARD New Recruits in the Armies of Shelaman: Notes from a Primary Man MODERATING THE 04 AWAKENINGS Rob McFarland Making Peace with Mystery: To Prophet Jonah MORMON DISCOURSE ON MODESTY Mary B. Johnston 28 Reflections on a Wedding BY JENNIFER FINLAYSON-FIFE, WILMETTE, ILLINOIS Averyl Dietering 07 SISTERS SPEAK ON THE COVER: I believe the LDS cultural discourse around modesty is important because Sharing Experiences with Mothers’ Blessings 30 SABBATH PASTORALS Page Turner of its very real implications for women in the Church. How we construct Being Grateful for God’s Hand in a World I our sexuality deeply affects how we relate to ourselves and to one another. Moderating the Mormon Discourse on -

The Commissioned Flute Choir Pieces Presented By

THE COMMISSIONED FLUTE CHOIR PIECES PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY/COLLEGE FLUTE CHOIRS AND NFA SPONSORED FLUTE CHOIRS AT NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONVENTIONS WITH A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FLUTE CHOIR AND ITS REPERTOIRE DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yoon Hee Kim Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Russel C. Mikkelson Dr. Charles M. Atkinson Karen Pierson Copyright by Yoon Hee Kim 2013 Abstract The National Flute Association (NFA) sponsors a range of non-performance and performance competitions for performers of all ages. Non-performance competitions are: a Flute Choir Composition Competition, Graduate Research, and Newly Published Music. Performance competitions are: Young Artist Competition, High School Soloist Competition, Convention Performers Competition, Flute Choirs Competitions, Professional, Collegiate, High School, and Jazz Flute Big Band, and a Masterclass Competition. These competitions provide opportunities for flutists ranging from amateurs to professionals. University/college flute choirs perform original manuscripts, arrangements and transcriptions, as well as the commissioned pieces, frequently at conventions, thus expanding substantially the repertoire for flute choir. The purpose of my work is to document commissioned repertoire for flute choir, music for five or more flutes, presented by university/college flute choirs and NFA sponsored flute choirs at NFA annual conventions. Composer, title, premiere and publication information, conductor, performer and instrumentation will be included in an annotated bibliography format. A brief history of the flute choir and its repertoire, as well as a history of NFA-sponsored flute choir (1973–2012) will be included in this document. -

Primary 5 Manual: Doctrine and Covenants, Church History

References Information given in the historical accounts in each lesson was taken from the sources listed below. Lesson 1 Church History in the Fulness of Times (Church Educational System manual [32502], 1993), pp. 21–24, 29–36. Dean C. Jessee, ed. The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1984), p. 4. J. W. Peterson, “Another Testimony: Statement of William Smith, Concerning Joseph, the Prophet,” Deseret Evening News, 20 Jan. 1894, p. 11. Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith, ed. Preston Nibley (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1958), pp. 67, 82. Lesson 2 Church History in the Fulness of Times (Church Educational System manual [32502], 1993), pp. 3–10, 17. Milton V. Backman Jr. American Religions and the Rise of Mormonism, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1970), pp. 65–69, 179–81. Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), p. 185. Edwin Scott Gaustad, A Religious History of America (New York: Harper and Row, 1966), pp. 47–66. Lesson 3 Church History in the Fulness of Times (Church Educational System manual [32502], 1993), p. 37. Lesson 4 Church History in the Fulness of Times (Church Educational System manual [32502], 1993), pp. 41–43. J. W. Peterson, “Another Testimony: Statement of William Smith, Concerning Joseph, the Prophet,” Deseret Evening News, 20 Jan. 1894, p. 11. Lucy Mack Smith, History of Joseph Smith, ed. Preston Nibley (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1958), pp. 82–83, 87. Lesson 5 Church History in the Fulness of Times (Church Educational System manual [32502], 1993), pp. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley.