Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Crime Compounds Conflict

WHERE CRIME COMPOUNDS CONFLICT Understanding northern Mozambique’s vulnerabilities SIMONE HAYSOM October 2018 WHERE CRIME COMPOUNDS CONFLICT Understanding northern Mozambique’s vulnerabilities Simone Haysom October 2018 Cover photo: iStock/Katiekk2 Pemba, Mozambique: ranger with a gun looking at feet of elephants after poachers had killed the animals for illegal ivory trade © 2018 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Contents Summary and key findings ..............................................................................................................................................1 Background .........................................................................................................................................................................................2 The militants and funding from the illicit economy .......................................................................................4 Methodology .....................................................................................................................................................................................5 Corrosion, grievance and opportunity: A detailed picture -

July 2014 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • JULY 2014 Parenting Young Adults, p. 56 The Book of Mormon and the Gathering of Israel, p. 26 Brazil: A Century of Growth, p. 42 “Sometimes we become the lightning rod, and we must ‘take the heat’ for holding fast to God’s standards and doing His work. I testify that we need not be afraid if we are grounded in His doctrine. We may experience misunderstanding, criticism, and even false accusation, but we are never alone. Our Savior was ‘despised and rejected of men’ [Isaiah 53:3]. It is our sacred privilege to stand with Him!” Elder Robert D. Hales of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, “Stand Strong in Holy Places,” Ensign, May 2013, 50. Contents July 2014 Volume 44 • Number 7 YOUNG ADULT FEATURES 14 Becoming Perfect in Christ Elder Gerrit W. Gong The Savior’s perfection can help us overcome a perfectionist, self-critical, and unrealistic mind-set. 20 Faith in God’s Plan for Me Jessica George The Kirtland stone quarry taught me a valuable lesson about God’s hand in my life. 22 Keeping a Journal Your Way Tara Walker From online blogs to audio recordings, there are many ways to keep a journal. These ideas will help you find what works for you. FEATURES 26 The Book of Mormon, the Gathering of Israel, and the Second Coming 4 Elder Russell M. Nelson The Book of Mormon is God’s instrument to help accomplish two divine objectives. MESSAGES 32 Be Like Ammon FIRST PRESIDENCY MESSAGE Could Ammon’s story help you activate the members 4 The Promise of Hearts Turning in your ward or branch? President Henry B. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Staging Lusophony: politics of production and representation in theater festivals in Portuguese-speaking countries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70h801wr Author Martins Rufino Valente, Rita Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Staging Lusophony: politics of production and representation in theater festivals in Portuguese-speaking countries A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Rita Martins Rufino Valente 2017 © Copyright by Rita Martins Rufino Valente 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Staging Lusophony: politics of production and representation in theater festivals in Portuguese-speaking countries by Rita Martins Rufino Valente Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair My dissertation investigates the politics of festival curation and production in artist-led theater festivals across the Portuguese-speaking (or Lusophone) world, which includes Latin America, Africa, Europe, and Asia. I focus on uses of Lusophony as a tactics to generate alternatives to globalization, and as a response to experiences of racialization and marginalization stemming from a colonial past. I also expose the contradictory relation between Lusophony, colonialism, and globalization, which constitute obstacles for transnational tactics. I select three festivals where, I propose, the legacies of the colonial past, which include the contradictions of Lusophony, become apparent throughout the curatorial and production processes: Estação da Cena Lusófona (Portugal), Mindelact – Festival Internacional de Teatro do Mindelo (Cabo Verde), and Circuito de Teatro em Português (Brazil). -

Thesis Title Page with Pictures2

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University GIRLS IN WAR, WOMEN IN PEACE: REINTEGRATION AND (IN)JUSTICE IN POST-WAR MOZAMBIQUE Town Cape of University A MINOR DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN JUSTICE AND TRANSFORMATION LILLIAN K. BUNKER BNKLIL001 FACULTY OF THE HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN 2011 COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: Town Cape of University i UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN GRADUATE SCHOOL IN HUMANITIES DECLARATION BY CANDIDATE FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES I, Lillian Bunker, of 101 B W. McKnight Way #27, Grass Valley, California 95949 U.S.A. do hereby declare that I empower the University of Cape Town to produceTown for the purpose of research either the whole or any portion of the contents of my dissertation entitled Girls in War, Women in Peace: Reintegration and (In)justice in Post-war Mozambique in any manner whatsoever. -

LDS (Mormon) Temples World Map

LDS (Mormon) Temples World Map 155 operating temples · 14 temples under construction · 8 announced temples TEMPLES GOOGLE EARTH (KML) TEMPLES GOOGLE MAP TEMPLES HANDOUT (PDF) HIGH-RES TEMPLES MAP (GIF) Africa: 7 temples United States: 81 temples Alabama: 1 temple Aba Nigeria Temple Birmingham Alabama Temple † Abidjan Ivory Coast Temple Alaska: 1 temple Accra Ghana Temple Anchorage Alaska Temple † Durban South Africa Temple Arizona: 6 temples † Harare Zimbabwe Temple Gila Valley Arizona Temple, The Johannesburg South Africa Temple Gilbert Arizona Temple Kinshasa Democratic Republic of the Congo Mesa Arizona Temple † Temple Phoenix Arizona Temple Snowflake Arizona Temple Asia: 10 temples Tucson Arizona Temple† Bangkok Thailand Temple† California: 7 temples Cebu City Philippines Temple Fresno California Temple Fukuoka Japan Temple Los Angeles California Temple Hong Kong China Temple Newport Beach California Temple Manila Philippines Temple Oakland California Temple Sapporo Japan Temple Redlands California Temple Seoul Korea Temple Sacramento California Temple Taipei Taiwan Temple San Diego California Temple Tokyo Japan Temple Colorado: 2 temples http://www.ldschurchtemples.com/maps/ LDS (Mormon) Temples World Map Urdaneta Philippines Temple† Denver Colorado Temple Fort Collins Colorado Temple Europe: 14 temples Connecticut: 1 temple Hartford Connecticut Temple Bern Switzerland Temple Florida: 2 temples Copenhagen Denmark Temple Fort Lauderdale Florida Temple ‡ Frankfurt Germany Temple Orlando Florida Temple Freiberg Germany Temple Georgia: -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

1 and 2 Nephi: an Inspiring Whole

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 26 Issue 4 Article 4 10-1-1986 1 And 2 Nephi: An Inspiring Whole Frederick W. Axelgard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Axelgard, Frederick W. (1986) "1 And 2 Nephi: An Inspiring Whole," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 26 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol26/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Axelgard: 1 And 2 Nephi: An Inspiring Whole I11 and 2 nephi an inspiring whole frederick W axelgard how inspired do we believe the scriptures to be do we justifiably confine ourselves to a verse by verse study of their doctrinal or didactic content are we missing much of the intended impact if we do not believe that entire sections chapters or books were organized under inspiration spiritualinspiritualunspiritualIn no less than literary terms could not the whole of a scriptural text amount to more than the sum of its I1 I1 parts these questions suggest an approach to scripture study which seeks to integrate rather than fragment the meaning of scriptural passages the spirit of this approach pervades the following observation which comments on those sections of the doctrine and covenants revealed in 1831 As we follow the development from section to section we perceive -

Byu Religious Education WINTER 2015 REVIEW

byu religious education WINTER 2015 REVIEW CALENDAR COMMENTS INTERVIEWS & SPOTLIGHTS STUDENT & TEACHER UPDATES BOOKS Keith H. Meservy Off the Beaten Path message from the deans’ office The Blessing of Positive Change B righam Young University’s Religious Studies Center (RSC) turns forty this year. Organized in 1975 by Jeffrey R. Holland, then dean of Religious Instruction, the RSC has been the means of publishing and disseminat- ing some of the best Latter-day Saint scholarship on the Church during the past four decades. The RSC continues to be administered and supported by Religious Education. One notable example of RSC publishing accomplish- ments is the journal Religious Educator. Begun in 2000, this periodical continues to provide insightful articles for students of scripture, doctrine, and quality teaching and learning practices. Gospel teachers in wards and branches around the world as well as those employed in the Church Educational System continue to access this journal through traditional print and online options. Alongside the Religious Educator, important books continue to be published by the RSC. For example, the RSC published the Book of Mormon Symposium Series, which has resulted in nine volumes of studies on this key Restoration scripture (1988–95). Two other important books from 2014 are By Divine Design: Best Practices for Family Success and Happiness and Called to Teach: The Legacy of Karl G. Maeser. For some years now the RSC has also provided research grants to faculty at BYU and elsewhere who are studying a variety of religious topics, texts, and traditions. And the RSC Dissertation Grant helps provide funds for faithful Latter-day Saint students who are writing doctoral dissertations on religious topics. -

J. Kirk Richards

mormonartist Issue 1 September 2008 inthisissue Margaret Blair Young & Darius Gray J. Kirk Richards Aaron Martin New Play Project editor.in.chief mormonartist Benjamin Crowder covering the Latter-day Saint arts world proofreaders Katherine Morris Bethany Deardeuff Mormon Artist is a bimonthly magazine Haley Hegstrom published online at mormonartist.net and in print through MagCloud.com. Copyright © 2008 Benjamin Crowder. want to help? All rights reserved. Send us an email saying what you’d be Front cover paper texture by bittbox interested in helping with and what at flickr.com/photos/31124107@N00. experience you have. Keep in mind that Mormon Artist is primarily a Photographs pages 4–9 courtesy labor of love at this point, so we don’t Margaret Blair Young and Darius Gray. (yet) have any money to pay those who help. We hope that’ll change Paintings on pages 12, 14, 17–19, and back cover reprinted soon, though. with permission from J. Kirk Richards. Back cover is “Pearl of Great Price.” Photographs on pages 2, 28, and 39 courtesy New Play Project. Photograph on pages 1 and 26 courtesy Vilo Elisabeth Photography, 2005. Photograph on page 34 courtesy Melissa Leilani Larson. Photograph on page 35 courtesy Gary Elmore. Photograph on page 37 courtesy Katherine Gee. contact us Web: mormonartist.net Email: [email protected] tableof contents Editor’s Note v essay Towards a Mormon Renaissance 1 by James Goldberg interviews Margaret Blair Young & Darius Gray 3 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder J. Kirk Richards 11 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder Aaron Martin 21 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder New Play Project 27 interviewed by Benjamin Crowder editor’snote elcome to the pilot issue of what will hope- fully become a longstanding love affair with the Mormon arts world. -

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

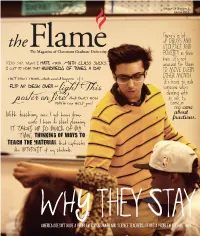

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

Reflections on a Lifetime with the Race Issue

SUNSTONE Twenty-five Years after the Revelation—Where Are We Now? REFLECTIONS ON A LIFETIME WITH THE RACE ISSUE By Armand L. Mauss HIS YEAR WE ARE COMMEMORATING THE resolution was forthcoming when the Presidency decided that twenty-fifth anniversary of the revelation extending the the benefit of the doubt should go to the parties involved. In due T priesthood to “all worthy males” irrespective of race or course, the young couple was married in the temple, but the res- ethnicity. My personal encounter with the race issue, however, olution came too late to benefit Richard. goes back to my childhood in the old Oakland Ward of My own wife Ruth grew up in a family stigmatized by the California. In that ward lived an elderly black couple named LDS residents of her small Idaho town because her father’s aunt Graves, who regularly attended sacrament meeting but (as far in Utah had earlier eloped with a black musician named as I can remember) had no other part in Church activities. Tanner in preference to accepting an arranged polygamous Everyone in the ward seemed to treat them with cordial dis- marriage. Before Ruth’s parents could be married, the intended tance, and periodically Brother Graves would bear his fervent bride (Ruth’s mother) felt the need to seek reassurance from testimony on Fast Sunday. I could never get a clear under- the local bishop that the family into which she was to marry standing from my parents about what (besides color) made was not under any divine curse because of the aunt’s black them “different,” given their obvious faithfulness. -

The Pro-Democracy Faith Movement Prominent Religious Leaders Reflect on the Meaning of Democracy

JIM WATSON/STAFF JIM The Pro-Democracy Faith Movement Prominent Religious Leaders Reflect On the Meaning of Democracy Maggie Siddiqi, Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons, and Carol Lautier February 2021 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 3 The pro-democracy faith movement 6 The religious right’s anti-democratic turn 8 The values of the pro-democracy faith movement 9 Building an inclusive, democratic movement for a more inclusive democracy 10 Centering the experiences of Black Americans 12 Grounding democracy in a shared sense of community 13 Being political but nonpartisan 16 Meeting the urgency of the moment 19 Conclusion 20 About the authors 20 Acknowledgments 21 Appendix 24 Endnotes Introduction and summary This report was developed through a project with Auburn Seminary, which for more than 200 years has equipped leaders of faith and moral courage who are on the front lines fighting for the health and wholeness of U.S. society. The past year has been an incredible test for American democracy. The coronavirus crisis not only crippled America’s public health and economy, but it also necessitated new ways of voting in a presidential election. This incited new tactics for voter sup- pression that compounded long-standing efforts to hobble the voting power of com- munities of color. The electoral process was further compromised by a campaign of unfounded accusations of voter fraud. Then, following the election in November, the former president and certain factions of his allies attempted to overturn the results. Former President Trump was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for his role in inciting the deadly January 6 insurrection at the U.S.