Visions of Tsafendas: Literary Biography and the Limits of “Research”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download/Pdf/39666742.Pdf De Vries, Fred (2006)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Restless collection: Ivan Vladislavić and South African literary culture Katie Reid PhD Colonial and Postcolonial Cultures University of Sussex January 2017 For my parents. 1 Acknowledgments With thanks to my supervisor, Professor Stephanie Newell, who inspired and enabled me to begin, and whose drive and energy, and always creative generosity enlivened the process throughout. My thanks are due to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding the research. Thanks also to the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas in Austin, for a Dissertation Fellowship (2011-12); and to the School of English at the University of Sussex for grants and financial support to pursue the research and related projects and events throughout, and without which the project would not have taken its shape. I am grateful to all staff at the research institutions I have visited: with particular mention to Gabriela Redwine at the HRC; everyone at the National English Literary Museum, Grahamstown; and all those at Pan McMillan, South Africa, who provided access to the Ravan Press archives. -

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd Is Assassinated in the House of Assembly by a Parliamentary Messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd is assassinated in the House of Assembly by a parliamentary messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September. Balthazar J Vorster becomes Prime Minister on 13 September. 1967 The Terrorism Act is passed, in terms of which police are empowered to detain in solitary confinement for indefinite periods with no access to visitors. The public is not entitled to information relating to the identity and number of people detained. The Act is allegedly passed to deal with SWA/Namibian opposition and NP politicians assure Parliament it is not intended for local use. Besides being used to detain Toivo ya Toivo and other members of Ovambo People’s Organisation, the Act is used to detain South Africans. SAP counter-insurgency training begins (followed by similar SADF training in the following year). Compulsory military service for all white male youths is extended and all ex-servicemen become eligible for recall over a twenty-year period. Formation of the PAC armed wing, the Azanian Peoples Liberation Army (APLA). MK guerrillas conduct their first military actions with ZIPRA in north-western Rhodesia in campaigns known as Wankie and Sepolilo. In response, SAP units are deployed in Rhodesia. 1968 The Prohibition of Political Interference Act prohibits the formation and foreign financing of non-racial political parties. The Bureau of State Security (BOSS) is formed. BOSS operates independently of the police and is accountable to the Prime Minister. The PAC military wing attempts to reach South Africa through Botswana and Mozambique in what becomes known as the Villa Peri campaign. 1969 The ANC holds its first Consultative (Morogoro) Conference in Tanzania, and adopts the ‘Strategies and Tactics of the ANC’ programme, which includes its new approach to the ‘armed struggle’ and ‘political mobilisation’. -

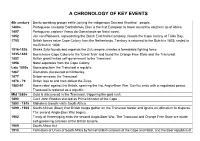

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire. -

Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for White South African Christians

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 10 Original Research Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for white South African Christians Author: A significant factor undermining real racial reconciliation in post-1994 South Africa is 1 Wilhelm J. Verwoerd widespread resistance to shared historical responsibility amongst South Africans racialised as Affiliation: white. In response to the need for localised ‘white work’ (raising self-critical, intragroup 1Studies in Historical Trauma historical awareness for the sake of deepened racial reconciliation), this article aims to Stellenbosch University, contribute to the uprooting of white denialism, specifically amongst Afrikaans-speaking Stellenbosch, South Africa Christians from (Dutch) Reformed backgrounds. The point of entry is two underexplored, Corresponding author: challenging, contextualised crucifixion paintings, namely, Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus. Wilhelm Johannes Verwoerd, Drawing on critical whiteness studies, extensive local and international experience as a [email protected] ‘participatory’ facilitator of conflict transformation and his particular embodiment, the author explores the creative unsettling potential of these two prophetic ‘icons’. Through this Dates: incarnational, phenomenological, diagnostic engagement with Black Christ, attention is drawn Received: 05 Oct. 2019 Accepted: 09 Mar. 2020 to the dynamics of family betrayal, ‘moral injury’ and idolisation underlying ‘white fragility’. Published: 30 July -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ...................................................... -

Three Studies of Ritual Sacrifice in Late-Capitalism

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ATLAS OF SACRIFICE: THREE STUDIES OF RITUAL SACRIFICE IN LATE-CAPITALISM A Dissertation in Communication Arts and Sciences by Keren Wang © 2018 Keren Wang Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 The dissertation of Keren Wang was reviewed and approved* by the following: Stephen H. Browne Liberal Arts Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Jeremy Engels Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Kirt H. Wilson Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and African American Studies CAS Graduate Program Chair Larry Catá Backer Professor of Law and International Affairs *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on one understudied rhetorical dynamic of late-capitalist governmentality – its deployment of ritual and sacrificial discourses. Ritual takings of things of human value, including ritual human sacrifice, has been continuously practiced for as long as human civilization itself has existed. It is important to note that ritual sacrifices were far more than simply acts of religious devotion. Ample historical records suggest ritual sacrifices were performed as crisis management devices. Large scale human sacrifices in Shang dynasty China were organized as responses to severe food shortages. Ancient Greece devised the specialized sacrificial forms of Holokaustos (total oblation) and Pharmakos (human scapegoat) as apotropaic responses to ward off catastrophes. The Aztec Empire introduced a highly institutionalized form of ritual warfare, known as the “Flower War” (Nahuatl: xōchiyāōyōtl), for the purpose of calendrical population control during periods of famine. -

Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions

NHBB Nationals Bee 2018-2019 Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions (1) An unsuccessful siege of the Jasna Gora Monastery during this conflict stiffened resistance by one side, which formed the Confederation of Tyszowce. Janusz Radziwill switched sides in this conflict by signing the Union of (+) Kedainiai. This conflict was ended by the Peace of Oliva and the Truce of Andrusovo and began with an uprising of Zaphorozian Cossacks which cost one side control of Ukraine, the (*) Khmelnytsky Uprising. Hetman Stefan Czarniecki helped John Casimir II drive out the invading armies of Alexis I and Charles X in this conflict. For the points, name this devastating Russian and Swedish invasion which broke the power of Poland-Lithuania. ANSWER: The Deluge (accept the Swedish Deluge or the Russian Deluge, accept First or Second Northern War, prompt on Northern Wars, prompt on Russo-Polish War, prompt on Swedish-Polish War, do not accept or prompt on Great Northern War) (2) In a speech delivered in this city, William Seward remarked that the incompatibility of slave states and free states presented an \irrepressible conflict,” which could lead to civil war. One of the final stops on the Underground Railroad was in this city's (+) Kelsey Landing, located along the Genesee River. Met with controversy due to her sex, Abigail Post was elected as the presiding officer of a convention in this city, where the (*) Declaration of Sentiments was approved two weeks after its introduction at the Seneca Falls Convention. Justice Ward Hunt fined a woman one hundred dollars for casting a vote in this city. -

South Africa, Prime Minister Hendrik F

Southern Africa Political Developments XHROUGHOUT Southern Africa, 1966 was a turbulent year. In the Republic of South Africa, Prime Minister Hendrik F. Verwoerd led the Na- tionalists to a sweeping election victory, only to be assassinated a few months later. In a decision generally regarded as a victory for South Africa, the In- ternational Court of Justice refused to pass on the merits of the suit by Ethiopia and Liberia to invalidate South Africa's administration of South West Africa. The United Nations General Assembly then adopted a resolu- tion revoking the mandate over South West Africa, declaring that it reverted to direct UN jurisdiction, and setting up a committee to consider ways of asserting this authority. Elsewhere, the High Commission territories of Bechuanaland and Basuto- land became the independent states of Botswana and Lesotho. The conflict precipitated by Rhodesia's unilateral declaration of independence in 1965 continued and intensified, with political and economic repercussions through- out the entire area. South Africa The South African economy remained prosperous in 1966. South Africa benefited to some extent from the Rhodesian conflict. For example, Zam- bia, seeking to reduce her own trade with Rhodesia, found South Africa the best available substitute source of some manufactured goods and coal. The government sought to curb a sharp inflationary trend by imposing credit and price controls, and relaxing restrictions on imports. In the campaign leading to the South African general election of March 30, the opposition United party charged that the Verwoerd government was giving inadequate support to the Smith regime in Rhodesia, and that it was opening the way to a partition of South Africa by promising eventual inde- pendence to the "Bantustans" established under the program of "'separate development." The first charge did not impress the electorate since the gov- ernment, while officially neutral and withholding formal recognition from the Smith regime, was giving it massive assistance in counteracting the effects of sanctions. -

Political Struggle in the 20Th Century

University of California UCOP | Political struggle in the 20th century [MUSIC PLAYING] In my lecture today, what I'd like to do is focus on developments in South Africa in the 20th century and to look at the struggle that took place by people trying to get to independence and freedom for themselves in a country that was ruled as a white supremacist state, either as adopting a form of government that was known prior to 1948 as segregation-- that is, the separation by people on the basis of their race. And that was given another name after 1948. And that is the word apartheid, meaning separate or apartness, and generally correctly pronounced as it can sometimes be pronounced by people who want to emphasize the political impression. They want to play with the word, and that is "a-part-hate," not "a-part-heid." What I want to look at is the development of a series of policies and people from the early part of the 20th century up through the 1960s when apartheid is really getting put fully into force. And let's look at some images of people so we can counterpose them as time goes on. This image I showed you in the Time magazine's survey of Africa in its covers. This was the first cover of anyone from Africa. In this case, it was JBM Hertzog. JBM Hertzog had been a soldier in the Anglo-Boer War as it's sometimes known, or the Boer War, or as historians would now call it, the South African War, between 1899 and 1902 when the British had fought to defeat those people who called themselves Afrikaners. -

Christianity and Community Development in Igboland, 1960-2000

AFRREV IJAH, Vol.1 (2) May, 2012 AFRREV IJAH An International Journal of Arts and Humanities Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Vol. 1 (2), May, 2012:133-141 ISSN: 2225-8590 (Print) ISSN 2227-5452 (Online) Nelson Mandela and the politics of representation in Robben Island Museum, South Africa Nwafor, Okechukwu Department of Fine and Applied Arts Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In the post apartheid South Africa, Nelson Mandela emerges as the chief icon of political imprisonment in the narration of Robben Island Museum. The predominating conception of Mandela as the former prisoner emeritus of Robben Island continues to attract public discourse and as a matter of fact has become the narrative iconography of Robben Island in the eyes of international visitors. This article examines how and why such narratives persist. This is done by analyzing how the Jetty 1 exhibition has attempted to engage this dominant ideology. 133 Copyright © IAARR 2012: www.afrrevjo.net/afrrevijah AFRREV IJAH, Vol.1 (2) May, 2012 The making of Nelson Mandela 1948 was a remarkable year in the history of African National Congress in South Africa. The African National Congress Youth League was formed in 1948 followed by the adoption of the Youth League Programme of Action against the white led apartheid government. Nelson Madela was elected the Secretary General of this Youth league. This position attracted wide publicity to Nelson Mandela especially with his new visibility and responsibility on the national level. The 1948 Youth League Programme culminated in Defiance Campaign against unjust laws in 1952. -

Historical Events, Trauma and Memory in South African Video Art (J0 Ractliffe, Penny Siopis, Berni Searle, Minnette Vári)

1 PRECARIOUS VIDEO: HISTORICAL EVENTS, TRAUMA AND MEMORY IN SOUTH AFRICAN VIDEO ART (J0 RACTLIFFE, PENNY SIOPIS, BERNI SEARLE, MINNETTE VÁRI) PhD DISSERTATION – HISTORY OF ART VOLUME 1 Yvette Mariette Greslé History of Art University College London January 2015 2 Declaration I, Yvette Mariette Greslé, confirm that the work presented in this dissertation is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the dissertation. 3 Abstract This dissertation explores four recent examples of video art by four South African women artists. It focuses on Jo Ractliffe’s Vlakplaas: 2 June 1999 (drive-by shooting) [1999/2000], Berni Searle’s Mute (2008), Penny Siopis’ Obscure White Messenger (2010) and Minnette Vári’s Chimera (the white edition, 2001 and the black edition 2001-2002). I consider the visual, sonic, temporal, durational, spatial, sensory and affective capacities of these works, and their encounter with historical events/episodes and figures the significance and affective charge of which move across the eras differentiated as apartheid and post-apartheid. I seek to contribute to critiques of the post-apartheid democracy, and the impetus to move forward from the past, to forgive and reconcile its violence, while not actively and critically engaging historical trauma, and its relation to memory. Each of the videos engaged enter into a dialogue with historical narratives embedded within the experience and memory of violence and racial oppression in South Africa. The study is concerned with the critical significance and temporality of memory in relation to trauma as a historical and psychoanalytical concept applicable to ongoing conditions of historical and political violence and its continuous, apparently irresolvable repetition in political-historical life. -

Rethinking White Societies in Southern Africa

Rethinking White Societies in Southern Africa This book showcases new research by emerging and established scholars on white workers and the white poor in Southern Africa. Rethinking White Societies in Southern Africa challenges the geographical and chronological limitations of existing scholarship by presenting case studies from Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe that track the fortunes of nonhegemonic whites during the era of white minority rule. Arguing against prevalent understandings of white society as uniformly wealthy or culturally homogeneous during this period, it demonstrates that social class remained a salient element throughout the twentieth century, how Southern Africa’s white societies were often divided and riven with tension and how the resulting social, political and economic complexities animated white minority regimes in the region. Addressing themes such as the class-based disruption of racial norms and practices, state surveillance and interventions – and their failures – towards nonhegemonic whites, and the opportunities and limitations of physical and social mobility, the book mounts a forceful argument for the regional consideration of white societies in this historical context. Centrally, it extends the path-breaking insights emanating from scholarship on racialized class identities from North America to the African context to argue that race and class cannot be considered independently in Southern Africa. This book will be of interest to scholars and students of Southern African studies, African history and the history of race. Duncan Money is a historian of Southern Africa whose research focuses on the mining industry. He is currently a researcher at the African Studies Centre, Leiden University, Netherlands and was previously a postdoctoral fellow at the International Studies Group, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.