Christianity and Community Development in Igboland, 1960-2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malibongwe Let Us Praise the Women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn

Malibongwe Let us praise the women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn In 1990, inspired by major political changes in our country, I decided to embark on a long-term photographic project – black and white portraits of some of the South African women who had contributed to this process. In a country previously dominated by men in power, it seemed to me that the tireless dedication and hard work of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters needed to be highlighted. I did not only want to include more visible women, but also those who silently worked so hard to make it possible for change to happen. Due to lack of funding and time constraints, including raising my twin boys and more recently being diagnosed with cancer, the portraits have been taken intermittently. Many of the women photographed in exile have now returned to South Africa and a few have passed on. While the project is not yet complete, this selection of mainly high profile women represents a history and inspiration to us all. These were not only tireless activists, but daughters, mothers, wives and friends. Gisele Wulfsohn 2006 ADELAIDE TAMBO 1929 – 2007 Adelaide Frances Tsukudu was born in 1929. She was 10 years old when she had her first brush with apartheid and politics. A police officer in Top Location in Vereenigng had been killed. Adelaide’s 82-year-old grandfather was amongst those arrested. As the men were led to the town square, the old man collapsed. Adelaide sat with him until he came round and witnessed the young policeman calling her beloved grandfather “boy”. -

Download This Report

Military bases and camps of the liberation movement, 1961- 1990 Report Gregory F. Houston Democracy, Governance, and Service Delivery (DGSD) Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) 1 August 2013 Military bases and camps of the liberation movements, 1961-1990 PREPARED FOR AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: FUNDED BY: NATIONAL HERITAGE COUNCI Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: ANC and PAC internal camps/bases, 1960-1963 ........................................................7 Chapter 4: Freedom routes during the 1960s.............................................................................. 12 Chapter 5: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1960s ............................................ 21 Chapter 6: Freedom routes during the 1970s and 1980s ............................................................. 45 Chapter 7: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1970s and 1980s ........................... 57 Chapter 8: The ANC’s prison camps ........................................................................................ -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

Statements from the Dock Mary

Author : Mary Benson The Sun will Rise: Statements from the Dock by Southern African Political Prisoners Contents James April Introduction Mosioua Robert Lekota Sobukwe Maitshe Nelson Mokoape Mandela Raymond Walter Sisulu Suttner Elias Mosima Motsoaledi Sexwale Andrew Naledi Tsiki Mlangeni Martin Wilton Mkwayi Ramokgadi Bram Fischer Isaac Seko Toivo ja Toivo Stanley Eliaser Nkosi Tuhadeleni Petrus Mothlanthe 1 Introduction This collection of statements made during political trials since 1960 testifies to the high courage, determination and humanity which distinguish the struggle for liberation and for a just society in South Africa and Namibia. The earliest of the statements in the collection is by Robert Sobukwe, late leader of the Pan-Africanist Congress. It expresses a theme running through all the statements: "The history of the human race has been a struggle for the removal of oppression, and we would have failed had we not made our contribution. We are glad we made it". Nelson Mandela`s powerful statement in Pretoria`s Palace of Justice on 20 April 1964, when he and other members of the African National Congress and the Congress Alliance were in the dock in the Rivonia Trial, has become an historic document. Two years later Bram Fischer QC, the advocate who had led the Rivonia defence, was himself on trial in the same court. A large part of the statements made by these two men is reproduced here, along with less well known statements by others on trial during the 1960s. This was the period immediately after the ANC and the PAC were outlawed. The liberation movement`s long-maintained policy of non-violence was finally abandoned for sabotage and armed struggle. -

Download/Pdf/39666742.Pdf De Vries, Fred (2006)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Restless collection: Ivan Vladislavić and South African literary culture Katie Reid PhD Colonial and Postcolonial Cultures University of Sussex January 2017 For my parents. 1 Acknowledgments With thanks to my supervisor, Professor Stephanie Newell, who inspired and enabled me to begin, and whose drive and energy, and always creative generosity enlivened the process throughout. My thanks are due to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding the research. Thanks also to the Harry Ransom Center, at the University of Texas in Austin, for a Dissertation Fellowship (2011-12); and to the School of English at the University of Sussex for grants and financial support to pursue the research and related projects and events throughout, and without which the project would not have taken its shape. I am grateful to all staff at the research institutions I have visited: with particular mention to Gabriela Redwine at the HRC; everyone at the National English Literary Museum, Grahamstown; and all those at Pan McMillan, South Africa, who provided access to the Ravan Press archives. -

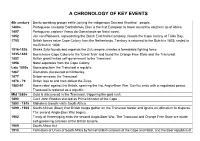

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd Is Assassinated in the House of Assembly by a Parliamentary Messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September

Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd is assassinated in the House of Assembly by a parliamentary messenger, Dimitri Tsafendas on 6 September. Balthazar J Vorster becomes Prime Minister on 13 September. 1967 The Terrorism Act is passed, in terms of which police are empowered to detain in solitary confinement for indefinite periods with no access to visitors. The public is not entitled to information relating to the identity and number of people detained. The Act is allegedly passed to deal with SWA/Namibian opposition and NP politicians assure Parliament it is not intended for local use. Besides being used to detain Toivo ya Toivo and other members of Ovambo People’s Organisation, the Act is used to detain South Africans. SAP counter-insurgency training begins (followed by similar SADF training in the following year). Compulsory military service for all white male youths is extended and all ex-servicemen become eligible for recall over a twenty-year period. Formation of the PAC armed wing, the Azanian Peoples Liberation Army (APLA). MK guerrillas conduct their first military actions with ZIPRA in north-western Rhodesia in campaigns known as Wankie and Sepolilo. In response, SAP units are deployed in Rhodesia. 1968 The Prohibition of Political Interference Act prohibits the formation and foreign financing of non-racial political parties. The Bureau of State Security (BOSS) is formed. BOSS operates independently of the police and is accountable to the Prime Minister. The PAC military wing attempts to reach South Africa through Botswana and Mozambique in what becomes known as the Villa Peri campaign. 1969 The ANC holds its first Consultative (Morogoro) Conference in Tanzania, and adopts the ‘Strategies and Tactics of the ANC’ programme, which includes its new approach to the ‘armed struggle’ and ‘political mobilisation’. -

International Dimensions, 1960-1967

INTERNATIONAL nternational support for what THE TURN TO ARMED STRUGGLE became Umkhonto we Sizwe I(MK) was forthcoming soon after the South African Communist Party © Shutterstock.com International Dimensions, (SACP) decided at its December 1960 conference to authorise the training of 1960-1967 a nucleus of fighters capable of leading a shift to violent methods, should the broader African National Congress (ANC) led liberation movement decide on a change of tactics. Arthur Goldreich was then a sub- manager in the Checkers store chain. The SACP’s Central Committee tasked him, using his job as cover, to explore the possibility of obtaining arms from Czechoslovakia. While the project was in its infancy, the Central Committee learned that the Chinese Communist Party was prepared to accept six people for military, Marxist and scholastic training. They selected Wilton Mkwayi, Nandha Naidoo, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni, Abel Mthembu and Joe Gqabi to receive the training. The six gathered in Peking towards the end of 1961 before separating in January 1962, with Mlangeni and Naidoo heading north for radio training, and the remainder south to Nanking for military training in the use of guns, hand grenades, and explosives. Within South Africa, the ANC and its alliance partners met at a beach house near Stanger a couple of months after the failure of a three-day stay- at-home that Nelson Mandela had organised for the eve of the country’s proclamation as a republic on 31 May 1961. The purpose of the Congress Alliance meeting was to reconsider the movement’s tactics in the wake of the strike. -

Former President Thabo Mbeki's Letter to ANC President Jacob Zuma

Former President Thabo Mbeki’s letter to ANC President Jacob Comrade President, I imagine that these must be especially trying times for you as president of our movement, the ANC, as they are for many of us as ordinary members of our beloved movement, which we have strived to serve loyally for many decades. I say this to apologise that I impose an additional burden on you by sending you this long letter. I decided to write this letter after I was informed that two days ago, on October 7, the president of the ANC Youth League and you the following day, October 8, told the country, through the media, that you would require me to campaign for the ANC during the 2009 election campaign. As you know, neither of you had discussed this with me prior to your announcements. Nobody in the ANC leadership - including you, the presidents of the ANC and ANCYL - has raised this matter with me since then. To avoid controversy, I have declined all invitations publicly to indicate whether I intended to act as you indicated or otherwise. In truth your announcements took me by surprise. This is because earlier you had sent Comrades Kgalema Motlanthe and Gwede Mantashe to inform me that the ANC NEC and our movement in general had lost confidence in me as a cadre of our movement. They informed me that for this reason you suggested that I should resign my position as president of the Republic, which I did. I therefore could not understand how the same ANC which was so disenchanted with me could, within a fortnight, consider me such a dependable cadre as could be relied upon to promote the political fortunes of the very same movement, the ANC, which I had betrayed in such a grave and grevious manner as to require that I should be removed from the presidency of the Republic a mere six or seven months before the end of our term, as mandated by the masses of our people! Your public announcements I have mentioned came exactly at the moment when Comrade Mosiuoa "Terror" Lekota and other ANC comrades publicly raised various matters about our movement of concern to them. -

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire. -

Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for White South African Christians

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 10 Original Research Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus for white South African Christians Author: A significant factor undermining real racial reconciliation in post-1994 South Africa is 1 Wilhelm J. Verwoerd widespread resistance to shared historical responsibility amongst South Africans racialised as Affiliation: white. In response to the need for localised ‘white work’ (raising self-critical, intragroup 1Studies in Historical Trauma historical awareness for the sake of deepened racial reconciliation), this article aims to Stellenbosch University, contribute to the uprooting of white denialism, specifically amongst Afrikaans-speaking Stellenbosch, South Africa Christians from (Dutch) Reformed backgrounds. The point of entry is two underexplored, Corresponding author: challenging, contextualised crucifixion paintings, namely, Black Christ and Cross-Roads Jesus. Wilhelm Johannes Verwoerd, Drawing on critical whiteness studies, extensive local and international experience as a [email protected] ‘participatory’ facilitator of conflict transformation and his particular embodiment, the author explores the creative unsettling potential of these two prophetic ‘icons’. Through this Dates: incarnational, phenomenological, diagnostic engagement with Black Christ, attention is drawn Received: 05 Oct. 2019 Accepted: 09 Mar. 2020 to the dynamics of family betrayal, ‘moral injury’ and idolisation underlying ‘white fragility’. Published: 30 July -

24. Wilton Mkwayi

Chapter 24 Wilton Mkwayi Wilton Mkwayi1 is an ANC veteran who was active in Port Elizabeth before he was charged with treason in 1956. He managed to escape during the course of the Treason Trial and was among the first six MK cadres sent for military training in China in 1961. After the Rivonia arrests in 1963 he took over as commander-in-chief of MK from Raymond Mhlaba. I was born on the 17th December 1923 in the Chwarhu area in Middledrift. My parents never went to school. That area is very bad; it's a very dry area. We had difficulties all the time, for instance with ploughing, because the type of corn we planted was what the European people call kaffir corn, the Zimbas. Even if the mielie is there, it dies. But the Zimbas are better. During those days we had no wire to fence our ploughing fields. Nevertheless, we could feed everybody that was hungry. On one occasion some Europeans came to the village – we didn't know them – and they said this field is not good and it must be killed by poison. The mielies must not be eaten. They would come and say to you: “Wait for that one because it's healthier. This one has been injected.” But at that stage we had already eaten enough but no one was dying. They said after a certain period it would kill you. So we got frightened. At home we were seven children, four boys and three girls. The eldest one was Elena, then Zimasile, Zilindile, Mlungwana, Lowukazi, Zukile and Noncithakalo, the last-born. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report

VOLUME THREE Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction to Regional Profiles ........ 1 Appendix: National Chronology......................... 12 Chapter 2 REGIONAL PROFILE: Eastern Cape ..................................................... 34 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Eastern Cape........................................................... 150 Chapter 3 REGIONAL PROFILE: Natal and KwaZulu ........................................ 155 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in Natal, KwaZulu and the Orange Free State... 324 Chapter 4 REGIONAL PROFILE: Orange Free State.......................................... 329 Chapter 5 REGIONAL PROFILE: Western Cape.................................................... 390 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Western Cape ......................................................... 523 Chapter 6 REGIONAL PROFILE: Transvaal .............................................................. 528 Appendix: Statistics on Violations in the Transvaal ......................................................