24. Wilton Mkwayi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malibongwe Let Us Praise the Women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn

Malibongwe Let us praise the women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn In 1990, inspired by major political changes in our country, I decided to embark on a long-term photographic project – black and white portraits of some of the South African women who had contributed to this process. In a country previously dominated by men in power, it seemed to me that the tireless dedication and hard work of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters needed to be highlighted. I did not only want to include more visible women, but also those who silently worked so hard to make it possible for change to happen. Due to lack of funding and time constraints, including raising my twin boys and more recently being diagnosed with cancer, the portraits have been taken intermittently. Many of the women photographed in exile have now returned to South Africa and a few have passed on. While the project is not yet complete, this selection of mainly high profile women represents a history and inspiration to us all. These were not only tireless activists, but daughters, mothers, wives and friends. Gisele Wulfsohn 2006 ADELAIDE TAMBO 1929 – 2007 Adelaide Frances Tsukudu was born in 1929. She was 10 years old when she had her first brush with apartheid and politics. A police officer in Top Location in Vereenigng had been killed. Adelaide’s 82-year-old grandfather was amongst those arrested. As the men were led to the town square, the old man collapsed. Adelaide sat with him until he came round and witnessed the young policeman calling her beloved grandfather “boy”. -

Download This Report

Military bases and camps of the liberation movement, 1961- 1990 Report Gregory F. Houston Democracy, Governance, and Service Delivery (DGSD) Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) 1 August 2013 Military bases and camps of the liberation movements, 1961-1990 PREPARED FOR AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: FUNDED BY: NATIONAL HERITAGE COUNCI Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: ANC and PAC internal camps/bases, 1960-1963 ........................................................7 Chapter 4: Freedom routes during the 1960s.............................................................................. 12 Chapter 5: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1960s ............................................ 21 Chapter 6: Freedom routes during the 1970s and 1980s ............................................................. 45 Chapter 7: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1970s and 1980s ........................... 57 Chapter 8: The ANC’s prison camps ........................................................................................ -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

Statements from the Dock Mary

Author : Mary Benson The Sun will Rise: Statements from the Dock by Southern African Political Prisoners Contents James April Introduction Mosioua Robert Lekota Sobukwe Maitshe Nelson Mokoape Mandela Raymond Walter Sisulu Suttner Elias Mosima Motsoaledi Sexwale Andrew Naledi Tsiki Mlangeni Martin Wilton Mkwayi Ramokgadi Bram Fischer Isaac Seko Toivo ja Toivo Stanley Eliaser Nkosi Tuhadeleni Petrus Mothlanthe 1 Introduction This collection of statements made during political trials since 1960 testifies to the high courage, determination and humanity which distinguish the struggle for liberation and for a just society in South Africa and Namibia. The earliest of the statements in the collection is by Robert Sobukwe, late leader of the Pan-Africanist Congress. It expresses a theme running through all the statements: "The history of the human race has been a struggle for the removal of oppression, and we would have failed had we not made our contribution. We are glad we made it". Nelson Mandela`s powerful statement in Pretoria`s Palace of Justice on 20 April 1964, when he and other members of the African National Congress and the Congress Alliance were in the dock in the Rivonia Trial, has become an historic document. Two years later Bram Fischer QC, the advocate who had led the Rivonia defence, was himself on trial in the same court. A large part of the statements made by these two men is reproduced here, along with less well known statements by others on trial during the 1960s. This was the period immediately after the ANC and the PAC were outlawed. The liberation movement`s long-maintained policy of non-violence was finally abandoned for sabotage and armed struggle. -

International Dimensions, 1960-1967

INTERNATIONAL nternational support for what THE TURN TO ARMED STRUGGLE became Umkhonto we Sizwe I(MK) was forthcoming soon after the South African Communist Party © Shutterstock.com International Dimensions, (SACP) decided at its December 1960 conference to authorise the training of 1960-1967 a nucleus of fighters capable of leading a shift to violent methods, should the broader African National Congress (ANC) led liberation movement decide on a change of tactics. Arthur Goldreich was then a sub- manager in the Checkers store chain. The SACP’s Central Committee tasked him, using his job as cover, to explore the possibility of obtaining arms from Czechoslovakia. While the project was in its infancy, the Central Committee learned that the Chinese Communist Party was prepared to accept six people for military, Marxist and scholastic training. They selected Wilton Mkwayi, Nandha Naidoo, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni, Abel Mthembu and Joe Gqabi to receive the training. The six gathered in Peking towards the end of 1961 before separating in January 1962, with Mlangeni and Naidoo heading north for radio training, and the remainder south to Nanking for military training in the use of guns, hand grenades, and explosives. Within South Africa, the ANC and its alliance partners met at a beach house near Stanger a couple of months after the failure of a three-day stay- at-home that Nelson Mandela had organised for the eve of the country’s proclamation as a republic on 31 May 1961. The purpose of the Congress Alliance meeting was to reconsider the movement’s tactics in the wake of the strike. -

Former President Thabo Mbeki's Letter to ANC President Jacob Zuma

Former President Thabo Mbeki’s letter to ANC President Jacob Comrade President, I imagine that these must be especially trying times for you as president of our movement, the ANC, as they are for many of us as ordinary members of our beloved movement, which we have strived to serve loyally for many decades. I say this to apologise that I impose an additional burden on you by sending you this long letter. I decided to write this letter after I was informed that two days ago, on October 7, the president of the ANC Youth League and you the following day, October 8, told the country, through the media, that you would require me to campaign for the ANC during the 2009 election campaign. As you know, neither of you had discussed this with me prior to your announcements. Nobody in the ANC leadership - including you, the presidents of the ANC and ANCYL - has raised this matter with me since then. To avoid controversy, I have declined all invitations publicly to indicate whether I intended to act as you indicated or otherwise. In truth your announcements took me by surprise. This is because earlier you had sent Comrades Kgalema Motlanthe and Gwede Mantashe to inform me that the ANC NEC and our movement in general had lost confidence in me as a cadre of our movement. They informed me that for this reason you suggested that I should resign my position as president of the Republic, which I did. I therefore could not understand how the same ANC which was so disenchanted with me could, within a fortnight, consider me such a dependable cadre as could be relied upon to promote the political fortunes of the very same movement, the ANC, which I had betrayed in such a grave and grevious manner as to require that I should be removed from the presidency of the Republic a mere six or seven months before the end of our term, as mandated by the masses of our people! Your public announcements I have mentioned came exactly at the moment when Comrade Mosiuoa "Terror" Lekota and other ANC comrades publicly raised various matters about our movement of concern to them. -

A Nation Behind Bars

A NATION BEHIND BARS A.ZANZOLO NOBODY REALLY KNOWS how many political prisoners there are in South Africa. Estimates range from four to tcn thousand. For a long time it was thought that the number in the Eastern Cape was over nine hundred. Then the notorious Mr. Vorsler. who has now become Prime Minister of South Africa, revealed in Parliament that there were no less than 1,669 prisoners in the Eastern Cape alone! This was almost double the accepted estimate. This could mean there has been under-estimation of the national total. Bearing in mind that the authorities themselves will do everything to conceal the true Slate of affairs we can expect that the real figures are much higher than generally accepted. Robben Island. Glamorgan Prison in East London called KwaNongqongqo by the Africans. Lecukop prison on the Rand already a byword for brutality against prisoners. Port Elizabeth Central. Pieterntaritzburg gaol. Pretoria Central. Viljoensdrift. Kroon stad. Umtata. Kokstad. The list is endless. There has always been a legend about Robben Island. The most persistent was built around the story of the famed war strategist and prophet Makana, otherwise known as Nxele(the left-handed). After the defeat of the AmaNdlambe in the fifth Eastern frontier war in 1819 Makana was sent to Robben Island as a prisoner of the British. Later the authorities let it be known that Makana had died whilst trying to escape from the island. The Africans were naturally suspicious of this version of Makana's death. It was prophesied that one day Makana would arise from Robben Island to lead the people in the struggle against the White invaders. -

The South African Liberation Movements in Exile, C. 1945-1970. Arianna Lissoni

The South African liberation movements in exile, c. 1945-1970. Arianna Lissoni This thesis is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, January 2008. ProQuest Number: 11010471 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010471 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the reorganisation in exile of the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) of South Africa during the 1960s. The 1960s are generally regarded as a period of quiescence in the historiography of the South African liberation struggle. This study partially challenges such a view. It argues that although the 1960s witnessed the progressive silencing of all forms of opposition by the apartheid government in South Africa, this was also a difficult time of experimentation and change, during which the exiled liberation movements had to adjust to the dramatically altered conditions of struggle emerging in the post-Sharpeville context. -

Govan Mbeki Awards

GOVAN MBEKI AWARDS BACKGROUND The purpose of the Govan Mbeki Awards is to promote and inculcate a culture of excellence within the Human Settlement sector in the delivery of quality Human Settlements and dignity to South Africans. Encourage all Stakeholders in the sector to respond systematically and foster the entrenchment of spatial patterns across all geographic scales that exacerbate social inequality and economic inefficiency. In addressing these patterns the Awards takes in to account the unique needs and potentials of different rural and urban areas in the context of emerging development corridors in the Southern African sub-region. Who is Govan Mbeki The Awards were named after Govan Mbeki in 2006 based on the role he played and vision he had on the preservation of human dignity and provision of human settlements for all. In all his work, he distinguished himself as a scholar, a disciplined cadre, a builder and a teacher. His students remember his distinctive, interactive and encouraging style of teaching, using methods which were well ahead of time. He built and sustained a tradition of excellent political journalism and theoretical writing. Together with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Elias Motsoaledi, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni, Wilton Mkwayi and Dennis Goldberg and he was sentenced to life imprisonment in Rivonia Trial by the apartheid government in 1964. Govan Mbeki was and remained a firm believer in the superior morality of socialism to his last day. Former President Nelson Mandela paid a moving tribute at the funeral of Govan Archibald Mvuyelwa Mbeki in September 2001 in Port Elizabeth: “I want you to know that (Govan) was one of the truly great sons of Africa and that we can take courage from his life. -

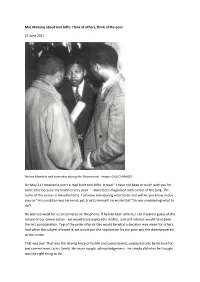

Mac Maharaj About Joel Joffe: Think of Others, Think of the Poor

Mac Maharaj about Joel Joffe: Think of others, think of the poor 25 June 2017 Nelson Mandela and comrades during the Rivonia trial. Image: GALLO IMAGES On May 21 I received a short e-mail from Joel Joffe. It read: "I have not been in touch with you for some time because my health is very poor ... I have been diagnosed with cancer of the lung. The name of the cancer is mesothelioma. I am now considering what to do and will let you know in due course." His condition was terminal, yet, true to himself, he wrote that "he was considering what to do"! He was too weak for us to converse on the phone. If he had been able to, I can hazard a guess at the nature of our conversation - we would have explored a matter, and self-interest would have been the last consideration. Top of the order of priorities would be what a decision may mean for others. And when the subject allowed it, we would put the implication for the poor and the disempowered at the centre. That was Joel. That was the driving force of his life and commitment, surpassed only by his love for and commitment to his family. He never sought acknowledgement - he simply did what he thought was the right thing to do. The Rivonia arrests In 1963 he was an attorney in the practice of Kantor and Wolpe when the Rivonia arrests took place. Kantor was detained. Wolpe was also detained, only to escape shortly thereafter. Almost by default, Joel became the instructing attorney in the Rivonia trial. -

SECOND ISSUE This Is the Second Number of a Bulletin Put out by the American Committee on Africa, a Private, Non-Profit Organiza

SECOND ISSUE This is the second number of a Bulletin put out by the American Committee on Africa, a private, non-profit organization, formed in 1953. The Committee has basically three important aims: 1. To promote African American understanding, through its monthly magazine, Africa Today, by pamphlets written by specialists, and also through presentation of outstanding Africans on the lecture platform. 2. To further the development of an American public opinion and a U.S. Government policy favorable to the complete liquidation of colonialism and white domination in Africa. Assistance is given to U .N. petitioners; meetings and conferences on such problems as South African apartheid are sponsored; and demonstrations are occasionally organized around specific events, __ 3. To raise funds for humanitarian assistance of critical African needs, especially where a political context precludes assistance from major relief groups . Thus, current emphasis is on aid to v1ctims of South African apartheid, and on medical relief to Angolans uprooted by the war in their homeland. FOUR MINI CHILDREN TRADING FOR LIVES Mini, Nkaba and Khayinga need not have died; they could have saved themselves at the last moment. All three left behind, in personal statements, the sordid details of official offers made to them to com mute their death sentences to life imprisonment if they would testify against a friend and associate, Wilton Mkwayi. They refused, and were hanged. One of their colleagues writes: "They chose to die rather than betray the freedom struggle and their just belief." The three patriots left widows and 13 children: Mini 5, ranging from 2 to 14 years of age, Khayinga 6, Nkosazana, 12 years old; Nomkhosi, 6, all small, Nkaba 2. -

One Particular Aspect of Umkhonto We Sizwe About Which Little Has Been

THE ORGANISATION, LEADERSHIP MID FINANCING OF UKlCHONTO lIE SIZE One partIcular aspect of Umkhonto we Sizwe about which little has been written since the beginning of the armed struggle in 1961, has been the organisation's structure, the nature of its leadership and its funding. This is not surprisIng, since revelations about how the organisation operated, who its leaders were, and who financed it, could be harmful if not destructive to its security. This is particularly true of the period between 1961 and the middle of the 1960's When the armed struggle was being conducted from within South Africa. During these early years no information was ever officially released by the ANC on any of its underground structures; their interrelations and functions or who was responsIble for what in the organisation. What is known about the organisation and leadership of Umkhonto and the underground during these early years, is largely based. on information revealed during the numerous court cases that involved the members or alleged members of the underground. ANC and the SACP and the research that has been undertaken by various scholars on the SUbject. Edward Felt was the first scholar to make extensive use of the abovementioned court material for research into the hIstory of the ANC, the SACP and Umkhonto between 1960 and 196!., As a result of the work done by him and the information contained in other sources such as Bruno Mtolo's book on Umkhonto a reasonably clear picture can be formed of the organisatlonal structure of Umkhonto and its leadership during this period.