Chapter Seventeen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malibongwe Let Us Praise the Women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn

Malibongwe Let us praise the women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn In 1990, inspired by major political changes in our country, I decided to embark on a long-term photographic project – black and white portraits of some of the South African women who had contributed to this process. In a country previously dominated by men in power, it seemed to me that the tireless dedication and hard work of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters needed to be highlighted. I did not only want to include more visible women, but also those who silently worked so hard to make it possible for change to happen. Due to lack of funding and time constraints, including raising my twin boys and more recently being diagnosed with cancer, the portraits have been taken intermittently. Many of the women photographed in exile have now returned to South Africa and a few have passed on. While the project is not yet complete, this selection of mainly high profile women represents a history and inspiration to us all. These were not only tireless activists, but daughters, mothers, wives and friends. Gisele Wulfsohn 2006 ADELAIDE TAMBO 1929 – 2007 Adelaide Frances Tsukudu was born in 1929. She was 10 years old when she had her first brush with apartheid and politics. A police officer in Top Location in Vereenigng had been killed. Adelaide’s 82-year-old grandfather was amongst those arrested. As the men were led to the town square, the old man collapsed. Adelaide sat with him until he came round and witnessed the young policeman calling her beloved grandfather “boy”. -

Download This Report

Military bases and camps of the liberation movement, 1961- 1990 Report Gregory F. Houston Democracy, Governance, and Service Delivery (DGSD) Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) 1 August 2013 Military bases and camps of the liberation movements, 1961-1990 PREPARED FOR AMATHOLE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY: FUNDED BY: NATIONAL HERITAGE COUNCI Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Literature review ........................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: ANC and PAC internal camps/bases, 1960-1963 ........................................................7 Chapter 4: Freedom routes during the 1960s.............................................................................. 12 Chapter 5: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1960s ............................................ 21 Chapter 6: Freedom routes during the 1970s and 1980s ............................................................. 45 Chapter 7: ANC and PAC camps and training abroad in the 1970s and 1980s ........................... 57 Chapter 8: The ANC’s prison camps ........................................................................................ -

Apartheid Kills, Apartheid Maims

June 1990 S The newspaper of the 3 Movement / 0p Apartheid kills, apartheid maims WUth FORZr ee%cpe I South Africa and Chile 0 Talks continue S Bantustans collapse * Black solidaity in ritain • Police action n IN =-DE: in arms cover-up page3 page 5 page6 aparthed page 2 page p 2 AIm-APARIJD man J= Im • ARMS EMBARGO South African G6 promoted as 'made in Chile' [ 4 Theatome of Be ll's 'vitory ton' of Europepresents a TheUnited Nations imposeda cleg dangorto the prospectsof freedom In South Africa. It is mandatory armsembargo on the prospect of the dinsmntlingof esting sanctions. SouthAfrica in 1977 outlaw Theantl-apartbeid movementsof te EuropeanCommunity ing allarms trading with the wereat one in oppasingBe Kirk's visit to Europe becauseIt apartheid regime.The arms cHf a a unacceptable degreeof respectabilityonthe head embargois theonly mandatory of sate of the apartheidregilo, andbecam, byreducing the embargo internationally pressure on the apartbeldregim, it couldunderlne the applied against SouthAfrica, [IT prospectsof achievinga pelitical settlent is Soth Africa. and aas wonafter manyyears" Boapartheid leader has prevlouslybeen ableto meetthe campaigning byanti-apartheid (socialist) presidentsar prim miaistors of France,Italy and organisationaroundthewor. Spain, the kings of Belgi and Spain, the presdnt ofthe EuropeanConmnity (socialist), andthe (conserative) heads of At the biennial FIDA arms 25 March by the new presi gosernmentof Brene, Portugaland Britia, withSwitzerland exhbitin inSantiago in March dent of Chile, the l55nsm thrownIn becauseof its Influence in banking andfinancial 21990, the Armscor G6 self weapons systems of South circles. Membersof the Socialist Groupin the European propelled 155mm howitzer African origin were brought Palament failed even to agrneon a remsolion mildly chiding was promoted asthe Cardoen into the exhibition-apparently acqnsDolors for mneting Be Kerk. -

Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of North Carolina School of Law NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 26 | Number 3 Article 5 Summer 2001 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Stephen Ellman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Stephen Ellman, To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity, 26 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 767 (2000). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol26/iss3/5 To Live Outside the Law You Must Be Honest: Bram Fischer and the Meaning of Integrity* Stephen Ellmann** Brain Fischer could "charm the birds out of the trees."' He was beloved by many, respected by his colleagues at the bar and even by political enemies.2 He was an expert on gold law and water rights, represented Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, the most prominent capitalist in the land, and was appointed a King's Counsel by the National Party government, which was simultaneously shaping the system of apartheid.' He was also a Communist, who died under sentence of life imprisonment. -

Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo

YUSUF MOHAMED DADOO SOUTH AFRICA'S FREEDOM STRUGGLE Statements, Speeches and Articles including Correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi Compiled and edited by E. S. Reddy With a foreword by Shri R. Venkataraman President of India Namedia Foundation STERLING PUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED New Delhi, 1990 [NOTE: A revised and expanded edition of this book was published in South Africa in 1991 jointly by Madiba Publishers, Durban, and UWC Historical and Cultural Centre, Bellville. The South African edition was edited by Prof. Fatima Meer. The present version includes items additional to that in the two printed editions.] FOREWORD TO THE INDIAN EDITION The South African struggle against apartheid occupies a cherished place in our hearts. This is not just because the Father of our Nation commenced his political career in South Africa and forged the instrument of Satyagraha in that country but because successive generations of Indians settled in South Africa have continued the resistance to racial oppression. Hailing from different parts of the Indian sub- continent and professing the different faiths of India, they have offered consistent solidarity and participation in the heroic fight of the people of South Africa for liberation. Among these brave Indians, the name of Dr. Yusuf Mohamed Dadoo is specially remembered for his remarkable achievements in bringing together the Indian community of South Africa with the African majority, in the latter's struggle against racism. Dr. Dadoo met Gandhiji in India and was in correspondence with him during a decisive phase of the struggle in South Africa. And Dr. Dadoo later became an esteemed colleague of the outstanding South African leader, Nelson Mandela. -

Narratives of Madikizela-Mandela's Testimony in Prison

The Power Dynamics and ‘Silent’ Narratives of Madikizela-Mandela’s Testimony in Prison Lebohang Motsomotso Abstract This article explores the underlying ontological violence that occurs in the oppressive structure of prisons. As a site of power dynamics, prisons are naturally defined based on inequalities and hierarchies. As such, they are marked by relationships of domination and subordination of prison wardens and prisoners respectively. Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s actions of resisting the power of the prison wardens becomes an instrument of challenging power. This power will be examined as phallic power and it signifies the overall oppressive systems. The prison experience becomes a mute narrative for Winnie Madikizela-Mandela who is imprisoned by a phallic power- driven system. It is a system that advocates for exercising control over prisoners by silencing and suppressing political convictions through a (il)legitimate system. Winnie Madikizela-Mandela functions as the focal point of discussion in this article through her experience, the argument that unfolds in this article illustrates the prime objective of the mechanics of power that operate in prison is to create docile bodies through, discipline that occurs by means of regulation, surveillance and isolation. Firstly, this article will outline how men monopolise power and how it is expressed and (re)presented through authority, reason, masculinity and dominance. Women are re(presented) through femininity, inferiority and lack of reason. Secondly, it explains and contextualises -

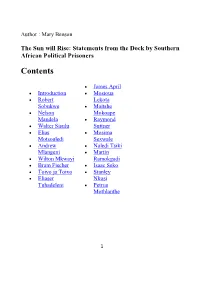

Statements from the Dock Mary

Author : Mary Benson The Sun will Rise: Statements from the Dock by Southern African Political Prisoners Contents James April Introduction Mosioua Robert Lekota Sobukwe Maitshe Nelson Mokoape Mandela Raymond Walter Sisulu Suttner Elias Mosima Motsoaledi Sexwale Andrew Naledi Tsiki Mlangeni Martin Wilton Mkwayi Ramokgadi Bram Fischer Isaac Seko Toivo ja Toivo Stanley Eliaser Nkosi Tuhadeleni Petrus Mothlanthe 1 Introduction This collection of statements made during political trials since 1960 testifies to the high courage, determination and humanity which distinguish the struggle for liberation and for a just society in South Africa and Namibia. The earliest of the statements in the collection is by Robert Sobukwe, late leader of the Pan-Africanist Congress. It expresses a theme running through all the statements: "The history of the human race has been a struggle for the removal of oppression, and we would have failed had we not made our contribution. We are glad we made it". Nelson Mandela`s powerful statement in Pretoria`s Palace of Justice on 20 April 1964, when he and other members of the African National Congress and the Congress Alliance were in the dock in the Rivonia Trial, has become an historic document. Two years later Bram Fischer QC, the advocate who had led the Rivonia defence, was himself on trial in the same court. A large part of the statements made by these two men is reproduced here, along with less well known statements by others on trial during the 1960s. This was the period immediately after the ANC and the PAC were outlawed. The liberation movement`s long-maintained policy of non-violence was finally abandoned for sabotage and armed struggle. -

John Brown's Body Lies A-Mouldering in Its Grave, but His Soul Goes

52 I THE NEW AFRICAN I MAY 1965 struggle of the South African people this man, a member of the privileged group. gave his life because of his passionate belief in racial equality. This will serve to strengthen the faith of all those who fight against the danget of a "race war" and retain their faith that all human beings can live together in dignity irrespective of the colour of their skin. I have, of course, known of Mr. John Harris and his activity in the movement against apartheid in sports for some time. Last July, a few days before his arrest, the attention of the Sub-Com mittee was drawn to a confidential A THIRD-GENERATION SOUTH AFRICAN, message from him on the question of Frederick John Harris was born in sports apartheid. 1937 and spent part of his childhood I have recently received a message on a farm at Eikenhof in the Transvaal. sent by him from his death cell in From earliest days his intellectual Pretoria Central Prison in January. He brilliance was recognised in the family wrote: circle. He became a radio "Quiz kid" "The support and warm sympathy of and his relatives, several of whom were friends has been and is among my basic teachers, used to say half-seriously of reinforcements. I daily appreciate the him that he would one day be Prime accuracy of the observation that when Minister. From an early age his main one really has to endure one relies ultimately on Reason and Courage. I've dream was of himself as a statesman been fortunate in that the first has stood in an ideal South Africa. -

Madikizela's a Human Being Died That Night

History, memory and reconciliation: Njabulo Ndebele’s The cry of Winnie Mandela and Pumla Gobodo- Madikizela’s A human being died that night Ralph Goodman Department of English University of Stellenbosch STELLENBOSCH E-pos: [email protected] Abstract History, memory and reconciliation: Njabulo Ndebele’s The cry of Winnie Mandela and Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela’s A human being died that night This article deals with two texts written during the process of transition in South Africa, using them to explore the cultural and ethical complexity of that process. Both Njabulo Ndebele’s “The cry of Winnie Mandela” and Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela’s “A human being died that night” deal with controversial public figures, Winnie Mandela and Eugene de Kock respectively, whose role in South African history has made them part of the national iconography. Ndebele and Gobodo-Madikizela employ narrative techniques that expose and exploit faultlines in the popular representations of these figures. The two texts offer radical ways of understanding the communal and individual suffering caused by apartheid, challenging readers to respond to the past in ways that will promote healing rather than perpetuate a spirit of revenge. The part played by official histories is implicitly questioned and the role of individual stories is shown to be crucial. Forgiveness and reconciliation are seen as dependent on an awareness of the complex circumstances and the humanity of those who are labelled as offenders. This requirement applies especially to the case of “A human being died that night”, a text that insists that the overt Literator 27(2) Aug. 2006:1-20 ISSN 0258-2279 1 History, memory and reconciliation: Njabulo Ndebele .. -

Umkhonto Wesizwe)

Spear of the Nation (Umkhonto weSizwe) SOUTH AFRICA’S LIBERATION ARMY, 1960s–1990s Janet Cherry OHIO UNIVERSITY PRESS ATHENS Contents Preface ....................................7 1. Introduction ............................9 2. The turn to armed struggle, 1960–3 ........13 3. The Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns, 1967–8 ................................35 4. Struggling to get home, 1969–84...........47 5. Reaping the whirlwind, 1984–9 ............85 6. The end of armed struggle...............113 7. A sober assessment of MK ...............133 Sources and further reading ................145 Index ...................................153 1 Introduction Hailed as heroes by many South Africans, demonised as evil terrorists by others, Umkhonto weSizwe, the Spear of the Nation, is now part of history. Though the organisation no longer exists, its former members are represented by the MK Military Veterans’ Association, which still carries some political clout within the ruling African National Congress (ANC). The story of MK, as Umkhonto is widely and colloquially known in South Africa, is one of paradox and contradiction, successes and failures. A people’s army fighting a people’s war of national liberation, they never got to march triumphant into Pretoria. A small group of dedicated revolutionaries trained by the Soviet Union and its allies, they were committed to the seizure of state power, but instead found their principals engaged in negotiated settlement with the enemy as the winds of global politics shifted in 9 the late 1980s. A guerrilla army of a few thousand soldiers in exile, disciplined and well trained, many of them were never deployed in battle, and most could not ‘get home’ to engage the enemy. Though MK soldiers set off limpet mines in public places in South Africa, killing a number of innocent civilians, they refrained from laying the anti-personnel mines that killed and maimed hundreds of thousands in other late-twentieth-century wars. -

We Were Cut Off from the Comprehension of Our Surroundings

Black Peril, White Fear – Representations of Violence and Race in South Africa’s English Press, 1976-2002, and Their Influence on Public Opinion Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von Christine Ullmann Institut für Völkerkunde Universität zu Köln Köln, Mai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The work presented here is the result of years of research, writing, re-writing and editing. It was a long time in the making, and may not have been completed at all had it not been for the support of a great number of people, all of whom have my deep appreciation. In particular, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Michael Bollig, Prof. Dr. Richard Janney, Dr. Melanie Moll, Professor Keyan Tomaselli, Professor Ruth Teer-Tomaselli, and Prof. Dr. Teun A. van Dijk for their help, encouragement, and constructive criticism. My special thanks to Dr Petr Skalník for his unflinching support and encouraging supervision, and to Mark Loftus for his proof-reading and help with all language issues. I am equally grateful to all who welcomed me to South Africa and dedicated their time, knowledge and effort to helping me. The warmth and support I received was incredible. Special thanks to the Burch family for their help settling in, and my dear friend in George for showing me the nature of determination. Finally, without the unstinting support of my two colleagues, Angelika Kitzmantel and Silke Olig, and the moral and financial backing of my family, I would surely have despaired. Thank you all for being there for me. We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. -

Detention Without Trial Saturday 19 March 1 Ruth and Louis Goldman

Detention without Trial Chapter 15 Page 1 Saturday 19 March 1 Ruth and Louis Goldman arrived today from Maritzburg to stay with us for a few days at 2 Ridsdale Avenue. After supper we started discussing the political situation, and we mentioned the rumours of another round of police raids to be made on members of the Congress movement as a result of the Anti Pass Campaign. Ruth and Louise became more and more uncomfortable as they realised that our house might be raided as well. Eventually we asked them whether they would rather stay with other friends in Durban to avoid the possibility of their being found in our house during a raid? After some discussion, they decided they would not stay with us after all; they left at about 11 p.m. in the pouring rain. Monday 21 March We heard on the radio today of the frightful massacre at Sharpeville in the Transvaal when the police opened fire on a peaceful demonstration outside the police station, protesting about the Pass Laws. There were many dead and a large number of wounded.2 1 I am starting off the beginning of this account as a daily diary 2 In Dr Sam Kleinot's obituary in October 2000, it is written that he was the surgeon in charge of Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto at the time, and that he was horrified to find that most of the dead and wounded had been shot in the back by the police. Detention without Trial Chapter 15 Page 2 Previous page: People fleeing from the police 3 Above: some of the dead 4 Right: police and a dead man 5 On several evenings during the next few days, I went to Harold Strachan's house on the Berea where several of us were busy duplicating thousands of leaflets for the Anti-Pass campaign.