Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Swordplay Through the Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects April 2008 Swordplay Through The Ages Daniel David Harty Worcester Polytechnic Institute Drew Sansevero Worcester Polytechnic Institute Jordan H. Bentley Worcester Polytechnic Institute Timothy J. Mulhern Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Harty, D. D., Sansevero, D., Bentley, J. H., & Mulhern, T. J. (2008). Swordplay Through The Ages. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/3117 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IQP 48-JLS-0059 SWORDPLAY THROUGH THE AGES Interactive Qualifying Project Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation by __ __________ ______ _ _________ Jordan Bentley Daniel Harty _____ ________ ____ ________ Timothy Mulhern Drew Sansevero Date: 5/2/2008 _______________________________ Professor Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Major Advisor Keywords: 1. Swordplay 2. Historical Documentary Video 3. Higgins Armory 1 Contents _______________________________ ........................................................................................0 Abstract: .....................................................................................................................................2 -

Whittaker-Annotated Atlbib July 31 2014

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version of August 2, 2014 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. I try in particular to note problems in some of the studies that are often cited by others with less atlatl knowledge, and correct some of the misinformation. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation, but at heart I am an old-fashioned paper-lover. -

SCOTLAND and the BRITISH ARMY C.1700-C.1750

SCOTLAND AND THE BRITISH ARMY c.1700-c.1750 By VICTORIA HENSHAW A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The historiography of Scotland and the British army in the eighteenth century largely concerns the suppression of the Jacobite risings – especially that of 1745-6 – and the growing assimilation of Highland soldiers into its ranks during and after the Seven Years War. However, this excludes the other roles and purposes of the British army, the contribution of Lowlanders to the British army and the military involvement of Scots of all origin in the British army prior to the dramatic increase in Scottish recruitment in the 1750s. This thesis redresses this imbalance towards Jacobite suppression by examining the place of Scotland and the role of Highland and Lowland Scots in the British army during the first half of the eighteenth century, at a time of change fuelled by the Union of 1707 and the Jacobite rebellions of the period. -

2021-22 Undergraduate Catalog

UNIVERSITY OF LYNCHBURG CATALOG One Hundred-Nineteenth Session 2021-22 Lynchburg, Virginia 24501-3113 Thank you for your interest in our undergraduate programs at the University of Lynchburg. This catalog represents the most current information available at the time of publica- tion for the academic year indicated on the cover. How- ever, the University may elect to make changes in the cur- riculum regulations or other aspects of this program. Thus, the provisions of this catalog are not to be regarded as an irrevocable contract between the University and the student. University of Lynchburg Lynchburg, VA 24501-3113 434.544.8100 2 University of Lynchburg TABLE OF CONTENTS ACADEMIC CALENDAR/CALENDAR OF EVENTS ............................................................................ 10 AN INTRODUCTION TO UNIVERSITY OF LYNCHBURG .................................................................. 12 Mission ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Institutional Values ..............................................................................................................................12 Accreditation ....................................................................................................................................... 13 History................................................................................................................................................. 13 University of Lynchburg Presidents -

British and American Perspectives on Early Modern Warfare

BEITRÄGE Peter Wilson British and american perspectives on early modern warfare Anglophone writing on warfare is currently undergoing a transformation, driven by a number of contradictory forces. In the US, as John Lynn has noted, ‘political correctness’ is stifling much traditional military history in the universities. Yet, conflict remains a central concern of academic study and social and political scientists are paying increasing attention to the past in their attempts to trace long-term human developments.1 Given the scope and volume of new work, this paper will eschew a comprehensive survey in favour of concentrating on the last decade, identifying key trends and important individual publications. The focus will be primarily on Anglophone writing on war as a historical phenomenon and as a factor in early modern British history. The revolution in social and economic history which swept British universities in the 1950s did not leave military history untouched. The new methodologies and concerns were incorporated to create what has become known as the ‘new military history’, or ‘war and society’ approach which seeks not merely to understand armed forces as social institutions, but to locate war in its wider historical context. This approach thrived in the 1970s and 1980s, epitomised by the ‘War and Society’ series originally published by Fontana and recently reissued by Sutton.2 It is maintained today by the journal, War in History, published by Arnold, as well as further individual volumes.3 While appreciating their insights, critics have charged the 1 Contrasting perspectives are offered by J. A. Lynn, The embattled future of academic military history, in: Journal of Military History 61 (1997), 777-789; J. -

Wall Street in Irish Affairs

FOUNDED 1939 j KEEP THE DATE FREE Organ of the AT a conference in June 1987, organised by the Connolly Association Connolly Association there will be a discussion on the democratic right cf the Irish people to unity and independence and the problems trade unionists face in generating support for this aim among other trade unionists. Before June there will be a number of meetings in which there will be preparatory discussions. The first of these will be on Saturday, 1st No 512 OCTOBER 1986 November, at the Marchmont Street Community Centre at 2.30 pm, chairman, Noel Harris national organiser of ACTT, main speaker C. Desmond Greaves. Many Trade Union Leaders expressed WALL STREET sympathetic interest at this year's Trades Union Congress. For further information write to or phone Connolly Association, 244, 246, Grays Inn Road, COONEYWANTS MEDDLES London, WC1. Tel: 833 3022. BIGGER LIES Teachers furious GOEBELS, Hitler's propaganda minister advocated the Big Lie. The historians have already been told to IN IRISH AFFAIRS play down the crimes of Britain in Ireland. That means the historians are already distorting history. The leaders U.S. SHOWS CONTEMPT FOR IRISH PEOPLE in'1916 must not be treated as heroes. Not content with that Mr Cooney Irish Minister for Education, wants teachers to introduce further distortion under his The cat is out of the bag good and proper guidance. In his circular he urges teachers to denounce "the evils of the IRA." THE cat is now out of the bag. Good and proper! The circular, sent to all post-primary HARRY COULDRING schools at the end of August, drew A prominent feature article in the prestigious Wall Street Journal, megaphone of the attention to the naming of 1986 by the multi-millionaires, argues that American policy towards Ireland should concentrate on one R.I.P. -

Weaponry from the Vassal House in Křivoklát Castle from the Early 15Th Century. Modernity Or Anachronism?

FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXXIII, PL ISSN 0860-0007 DOI 10.23858/FAH33.2020.013 JOSEF HLOŽEK*, OLGIERD ŁAWRYNOWICZ** WEAPONRY FROM THE VASSAL HOUSE IN KŘIVOKLÁT CASTLE FROM THE EARLY 15TH CENTURY. MODERNITY OR ANACHRONISM? Abstract: This paper aims at discussing an exceptionally well dated assemblage of pre-Hussite weaponry in Bohemia which survived in Křivoklát Castle. This castle was one of the most important medieval defensive seats of the kings of Bohemia. Archaeological examinations of the so-called Vassal House (Czech: Manský dům, German: Lehensmannshaus) which were carried out in the 1980s by Tomaš Durdík yielded important results which have not been published in full. In destruction layers of the feature which was an economic hinterland of the castle there were numerous remains of weaponry and military equipment, such as fragments of shafted weapons, crossbows, armours and individual finds of firearms. These artefacts are now a unique assemblage of weaponry from the period of intense transformation of Euro- pean arms and armour in the early 15th century. They are also a material testimony of existence of the castle garrison, which was composed of local vassals who were obliged to defend it. It is assumed that in the pre-Hussite period the garrison may have been composed of about 60 combatants, including nearly 40 shooters. Keywords: Křivoklát Castle, Manský dům, Medieval Period, weaponry, castle Received: 25.08.2020 Revised: 16.09.2020 Accepted: 07.10.2020 Citation: Hložek J., Ławrynowicz O. 2020. Weaponry from the Vassals House in Křivoklát from the 15th Century. Modernity or Anachro- nism? “Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae” 33, 183-199, DOI 10.23858/FAH33.2020.013 Introduction replaced by nearby Týřov as the central administration Křivoklát Castle in the Rakovník District is one castle in the area of this hunting forest.4 of Bohemia’s most significant castle sites. -

Historical Evolution of Roman Infantry Arms And

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF ROMAN INFANTRY ARMS AND ARMOR 753 BC - 476 AD An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment to the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By Evan Bossio Robert Chase Justin Dyer Stephanie Huang Marmik Patel Nathan Siegel Date: March 2, 2018 Submitted to: Professor Diana A. Lados Professor Luca Capogna Abstract During its time, the Roman Empire gained a formidable reputation as a result of its discipline and organization. The Roman Empire has made a lasting impact on the world due to its culture, political structure, and military might. The purpose of this project was to examine how the materials and processes used to create the weapons and armour helped to contribute to the rise and fall of the Roman Empire. This was done by analyzing how the Empire was able to successfully integrate new technologies and strategies from the regions the Empire conquered. The focus of this project is on the Empire's military, including the organization of the army, and the tactics and weapons used. To better understand the technology and innovations during this time the Roman long sword, spatha, was replicated and analyzed. 1 Acknowledgments The team would like to thank Professor Diana A. Lados and Professor Luca Capogna for this unique experience. The team would also like to thank Anthony Spangenberger for his guidance and time throughout the microstructure analysis. Lastly, this project could not have been done without Joshua Swalec, who offered his workshop, tools, and expertise throughout the manufacturing process 2 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgments 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 11 Authorship 12 1. -

Celts and Romans: the Transformation from Natural to Civic Religion Matthew at Ylor Kennedy James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2012 Celts and Romans: The transformation from natural to civic religion Matthew aT ylor Kennedy James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kennedy, Matthew Taylor, "Celts and Romans: The transformation from natural to civic religion" (2012). Masters Theses. 247. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celts and Romans: The Transformation from Natural to Civic Religion Matthew Kennedy A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History April 2012 Dedication To Verity, whose faith has been unwavering, and to my mother whose constant encouragement has let me reach this point. ii Table of Contents Dedication…………………………………………………………………………......ii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………….iv I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 II. Chapter 1: Early Roman Religion…..…………………………………………7 III. Chapter 2: Transition to Later Roman Religion.……………………………..23 IV. Chapter 3: Celtic Religion.…………………………………………………..42 V. Epilogue and Conclusion…………………………………………………….65 iii Abstract This paper is a case study dealing with cultural interaction and religion. It focuses on Roman religion, both before and during the Republic, and Celtic religion, both before and after Roman conquest. For the purpose of comparing these cultures two phases of religion are defined that exemplify the pagan religions of this period. -

Course Document

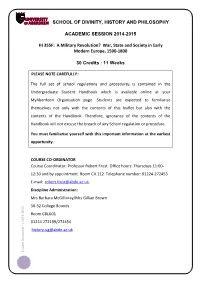

SCHOOL OF DIVINITY, HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY ACADEMIC SESSION 2014-2015 HI 355F: A Military Revolution? War, State and Society in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800 30 Credits : 11 Weeks 20TPLEASE NOTE CAREFULLY20T: The full set of school regulations and procedures is contained in the Undergraduate Student Handbook which is available online at your MyAberdeen Organisation page. Students are expected to familiarise themselves not only with the contents of this leaflet but also with the contents of the Handbook. Therefore, ignorance of the contents of the Handbook will not excuse the breach of any School regulation or procedure. You must familiarise yourself with this important information at the earliest opportunity. COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Course Coordinator: Professor Robert Frost. Office hours: Thursdays 11:00- 12:30 and by appointment. Room CA 112. Telephone number: 01224-272453. E-mail: [email protected] Discipline Administration: Mrs Barbara McGillivray/Mrs Gillian Brown 5 50-52 College Bounds 201 - Room CBLG01 4 201 | 01224 272199/272454 - [email protected] Course Document 1 TIMETABLE Please refer to the online timetable on 29TU MyAberdeenU29T Students can view the University Calendar at 29TUhttp://www.abdn.ac.uk/students/13891.phpU29T COURSE DESCRIPTION This course looks at the development of warfare in early modern Europe in the light of the theory, first proposed by Micheal Roberts, that Europe in this period saw a military revolution that had profound effects not just on the way wars were fought, but on European state formation and social development. It analyses the views of supporters and opponents of the theory, the technological changes seen in warfare in this period, and examines the conduct of war at the tactical and strategic levels, before going on to consider the changing culture of war and its impact on state and society. -

Georgetown Security Studies Review

0 Georgetown Security Studies Review Volume 8, Issue 2 November 2020 A Publication of the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service http://gssr.georgetown.edu 0 1|| Georgetown Security Studies Review Disclaimer The views expressed in Georgetown Security Studies Review do not necessarily represent those of the editors or staff of GSSR, the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, or Georgetown University. The editorial board of GSSR and its affiliated peer reviewers strive to verify the accuracy of all factual information contained in GSSR. However, the staffs of GSSR, the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, and Georgetown University make no warranties or representations regarding the completeness or accuracy of information contained in GSSR, and they assume no legal liability or responsibility for the content of any work contained therein. Copyright 2012–2020, Georgetown Security Studies Review. All rights reserved. Volume 8 || Issue 2 GEORGETOWN SECURITY STUDIES REVIEW Published by the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University’s Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service Editorial Board Samuel Seitz, Editor-in-Chief Caroline Nutt, Deputy Editor Lauren Finkenthal, Associate Editor for Africa Felipe Herrera, Associate Editor for Americas Daniel Cebul, Associate Editor for Europe Emma Jouenne, Associate Editor for Gender and IR Anna Liu, Associate Editor for Indo-Pacific Paul Kearney, Associate Editor for the Middle East Kelley Shaw, Associate Editor for National Security and the Military Shruthi Rajkumar, Associate Editor for South and Central Asia Talia Mamann, Associate Editor for Technology and Cyber Security Christopher Morris, Associate Editor for Terrorism and Counterterrorism The Georgetown Security Studies Review is the official academic journal of Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program.