Georgetown Security Studies Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

Whittaker-Annotated Atlbib July 31 2014

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version of August 2, 2014 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. I try in particular to note problems in some of the studies that are often cited by others with less atlatl knowledge, and correct some of the misinformation. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation, but at heart I am an old-fashioned paper-lover. -

SCOTLAND and the BRITISH ARMY C.1700-C.1750

SCOTLAND AND THE BRITISH ARMY c.1700-c.1750 By VICTORIA HENSHAW A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The historiography of Scotland and the British army in the eighteenth century largely concerns the suppression of the Jacobite risings – especially that of 1745-6 – and the growing assimilation of Highland soldiers into its ranks during and after the Seven Years War. However, this excludes the other roles and purposes of the British army, the contribution of Lowlanders to the British army and the military involvement of Scots of all origin in the British army prior to the dramatic increase in Scottish recruitment in the 1750s. This thesis redresses this imbalance towards Jacobite suppression by examining the place of Scotland and the role of Highland and Lowland Scots in the British army during the first half of the eighteenth century, at a time of change fuelled by the Union of 1707 and the Jacobite rebellions of the period. -

2021-22 Undergraduate Catalog

UNIVERSITY OF LYNCHBURG CATALOG One Hundred-Nineteenth Session 2021-22 Lynchburg, Virginia 24501-3113 Thank you for your interest in our undergraduate programs at the University of Lynchburg. This catalog represents the most current information available at the time of publica- tion for the academic year indicated on the cover. How- ever, the University may elect to make changes in the cur- riculum regulations or other aspects of this program. Thus, the provisions of this catalog are not to be regarded as an irrevocable contract between the University and the student. University of Lynchburg Lynchburg, VA 24501-3113 434.544.8100 2 University of Lynchburg TABLE OF CONTENTS ACADEMIC CALENDAR/CALENDAR OF EVENTS ............................................................................ 10 AN INTRODUCTION TO UNIVERSITY OF LYNCHBURG .................................................................. 12 Mission ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Institutional Values ..............................................................................................................................12 Accreditation ....................................................................................................................................... 13 History................................................................................................................................................. 13 University of Lynchburg Presidents -

British and American Perspectives on Early Modern Warfare

BEITRÄGE Peter Wilson British and american perspectives on early modern warfare Anglophone writing on warfare is currently undergoing a transformation, driven by a number of contradictory forces. In the US, as John Lynn has noted, ‘political correctness’ is stifling much traditional military history in the universities. Yet, conflict remains a central concern of academic study and social and political scientists are paying increasing attention to the past in their attempts to trace long-term human developments.1 Given the scope and volume of new work, this paper will eschew a comprehensive survey in favour of concentrating on the last decade, identifying key trends and important individual publications. The focus will be primarily on Anglophone writing on war as a historical phenomenon and as a factor in early modern British history. The revolution in social and economic history which swept British universities in the 1950s did not leave military history untouched. The new methodologies and concerns were incorporated to create what has become known as the ‘new military history’, or ‘war and society’ approach which seeks not merely to understand armed forces as social institutions, but to locate war in its wider historical context. This approach thrived in the 1970s and 1980s, epitomised by the ‘War and Society’ series originally published by Fontana and recently reissued by Sutton.2 It is maintained today by the journal, War in History, published by Arnold, as well as further individual volumes.3 While appreciating their insights, critics have charged the 1 Contrasting perspectives are offered by J. A. Lynn, The embattled future of academic military history, in: Journal of Military History 61 (1997), 777-789; J. -

Wall Street in Irish Affairs

FOUNDED 1939 j KEEP THE DATE FREE Organ of the AT a conference in June 1987, organised by the Connolly Association Connolly Association there will be a discussion on the democratic right cf the Irish people to unity and independence and the problems trade unionists face in generating support for this aim among other trade unionists. Before June there will be a number of meetings in which there will be preparatory discussions. The first of these will be on Saturday, 1st No 512 OCTOBER 1986 November, at the Marchmont Street Community Centre at 2.30 pm, chairman, Noel Harris national organiser of ACTT, main speaker C. Desmond Greaves. Many Trade Union Leaders expressed WALL STREET sympathetic interest at this year's Trades Union Congress. For further information write to or phone Connolly Association, 244, 246, Grays Inn Road, COONEYWANTS MEDDLES London, WC1. Tel: 833 3022. BIGGER LIES Teachers furious GOEBELS, Hitler's propaganda minister advocated the Big Lie. The historians have already been told to IN IRISH AFFAIRS play down the crimes of Britain in Ireland. That means the historians are already distorting history. The leaders U.S. SHOWS CONTEMPT FOR IRISH PEOPLE in'1916 must not be treated as heroes. Not content with that Mr Cooney Irish Minister for Education, wants teachers to introduce further distortion under his The cat is out of the bag good and proper guidance. In his circular he urges teachers to denounce "the evils of the IRA." THE cat is now out of the bag. Good and proper! The circular, sent to all post-primary HARRY COULDRING schools at the end of August, drew A prominent feature article in the prestigious Wall Street Journal, megaphone of the attention to the naming of 1986 by the multi-millionaires, argues that American policy towards Ireland should concentrate on one R.I.P. -

Celts and Romans: the Transformation from Natural to Civic Religion Matthew at Ylor Kennedy James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2012 Celts and Romans: The transformation from natural to civic religion Matthew aT ylor Kennedy James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kennedy, Matthew Taylor, "Celts and Romans: The transformation from natural to civic religion" (2012). Masters Theses. 247. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celts and Romans: The Transformation from Natural to Civic Religion Matthew Kennedy A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History April 2012 Dedication To Verity, whose faith has been unwavering, and to my mother whose constant encouragement has let me reach this point. ii Table of Contents Dedication…………………………………………………………………………......ii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………….iv I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 II. Chapter 1: Early Roman Religion…..…………………………………………7 III. Chapter 2: Transition to Later Roman Religion.……………………………..23 IV. Chapter 3: Celtic Religion.…………………………………………………..42 V. Epilogue and Conclusion…………………………………………………….65 iii Abstract This paper is a case study dealing with cultural interaction and religion. It focuses on Roman religion, both before and during the Republic, and Celtic religion, both before and after Roman conquest. For the purpose of comparing these cultures two phases of religion are defined that exemplify the pagan religions of this period. -

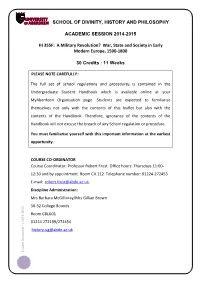

Course Document

SCHOOL OF DIVINITY, HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY ACADEMIC SESSION 2014-2015 HI 355F: A Military Revolution? War, State and Society in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800 30 Credits : 11 Weeks 20TPLEASE NOTE CAREFULLY20T: The full set of school regulations and procedures is contained in the Undergraduate Student Handbook which is available online at your MyAberdeen Organisation page. Students are expected to familiarise themselves not only with the contents of this leaflet but also with the contents of the Handbook. Therefore, ignorance of the contents of the Handbook will not excuse the breach of any School regulation or procedure. You must familiarise yourself with this important information at the earliest opportunity. COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Course Coordinator: Professor Robert Frost. Office hours: Thursdays 11:00- 12:30 and by appointment. Room CA 112. Telephone number: 01224-272453. E-mail: [email protected] Discipline Administration: Mrs Barbara McGillivray/Mrs Gillian Brown 5 50-52 College Bounds 201 - Room CBLG01 4 201 | 01224 272199/272454 - [email protected] Course Document 1 TIMETABLE Please refer to the online timetable on 29TU MyAberdeenU29T Students can view the University Calendar at 29TUhttp://www.abdn.ac.uk/students/13891.phpU29T COURSE DESCRIPTION This course looks at the development of warfare in early modern Europe in the light of the theory, first proposed by Micheal Roberts, that Europe in this period saw a military revolution that had profound effects not just on the way wars were fought, but on European state formation and social development. It analyses the views of supporters and opponents of the theory, the technological changes seen in warfare in this period, and examines the conduct of war at the tactical and strategic levels, before going on to consider the changing culture of war and its impact on state and society. -

Print This Article

EARLY MODERN CELTIC WARFARING Mathew Glozier Introduction Whenever the need arose and a war broke out … they all joined the battle.1 The whole race is war-mad, high-spirited and quick to battle.2 Caesar’s self-serving memoir of his Gallic wars (58-51 B.C.) reveals much about the ancient Celtic attitude towards war. Fighting was a key component of the life of the Celtic elite, but also pervaded the culture at all levels. The legends of other Celtic lands give a similar impression of small war bands, great heroes and large set-piece battles – much as Caesar himself described them in Gaul. From about the early fifth century B.C. in central Europe to its high- point in the third century B.C. the Celts came to dominate much of Europe, from Spain to Asia Minor. Their growth and expansion was not synonymous with war; trade and industry played a large part in their cultural primacy by the 200s B.C. However, war was the key to opposing the expansion of others, including Romans and the Germanic tribes. In the British Isles, Rome’s influence contained Celtic culture within Scotland, Wales and Ireland, and fifth century Christianisation challenged some Celtic practices. War was an all-male activity. Archaeological evidence suggests as many as half all adult males were buried with weaponry. Caesar reported the high level of ownership of weapons among some groups (did this make his victory sound all the more impressive?). 3 The typical Celtic warrior carried a spear over a metre long as well as short throwing spears and a large round shield of wood covered with leather and bearing a metal boss to protect the hand that gripped it. -

V60-I3-31-Gentles.Pdf (67.26Kb)

290 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS important a contribution to seventeenth-century studies as was The Paradise of Women. Mark Charles Fissel. English Warfare 1511-1642. London and New York: Routledge, 2001. xviii + 382 pp. + 38 illus. $25.95 [library edition $85]. Review by IAN GENTLES, GLENDON COL- LEGE, YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO. Mark Fissel advances a strong and ably-supported thesis– that the English accumulated a great deal of military experience in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, that they were conversant with the new techniques and technologies of the “mili- tary revolution,” that they sometimes achieved military victories against the best armies of Europe, that they were courageous, adapt- able, and eclectic, but that they refused to become a military cul- ture. He thus effectively challenges the argument of David Eltis and others that England was militarily backward and inexperi- enced during this period. English Warfare is grounded in a breathtakingly impressive quantity of research. It is densely factual, and up to date with the most recent historiography in the field. Fissel writes clearly, but his prose is some times less than sure-footed, resulting in a book that takes considerable effort to read. But the effort is rewarded. For example, Fissel highlights the relatively little-known fact that Elizabeth sent more men to the wars than her bellicose father. Her reasons were also more compelling than those of Henry VIII: the genuine defence of the realm and protestant commitment. It is surprising to learn that English involvement in the Dutch war of independence dated, not from the Earl of Leicester’s expedition of 1585-6, but from 1572, when Elizabeth sent a contingent of ‘vol- untaries.’ Within a few years these troops had won their spurs, demonstrating that they “could work in unison with allies, hold their ground, and perhaps even more importantly, maintain disci- pline in the crucible of battle, even against the best forces in Eu- rope” (141). -

Sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory Celine Savatier-Lahondès

Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory Celine Savatier-Lahondès To cite this version: Celine Savatier-Lahondès. Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Trough the Shakespearean Repertory. Linguistics. University of Stirling, 2019. English. NNT : 2019CLFAL012. tel-02439401 HAL Id: tel-02439401 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02439401 Submitted on 14 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. University of Stirling – Université Clermont Auvergne Transtextuality, (Re)sources and Transmission of the Celtic Culture Through the Shakespearean Repertory THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH.D) AND DOCTEUR DES UNIVERSITÉS (DOCTORAT) BY CÉLINE SAVATIER LAHONDÈS Co-supervised by: Professor Emeritus John Drakakis Professor Emeritus Danièle Berton-Charrière Department of Arts and Humanities IHRIM Clermont UMR 5317 University of Stirling Faculté de Lettres et Sciences Humaines Members of the Jury: -

International Politics and Warfare in the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Europe

INTERNATIONAL POLITICS AND WARFARE IN THE LATE MIDDLE AGES AND EARLY MODERN EUROPE A Bibliography of Diplomatic and Military Studies William Young Chapter 1 General Studies General Histories Andrews, Stuart. Eighteenth Century Europe: The 1680s to 1815. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1965. Bergin, Joseph, editor. Seventeenth Century Europe, 1598-1715. Short Oxford History of Europe series. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Birn, Raymond. Crisis, Absolutism, Revolution: Europe and the World, 1648- 1789. Third edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005. Black, Jeremy. Eighteenth Century Europe. Palgrave History of Europe series. Second edition. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. __________. AWarfare, Crisis, and Absolutism.@ In Early Modern Europe: An Oxford History. Edited by Euan Cameron. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Blanning, Timothy C.W. Pursuit of Glory: Europe, 1648-1815. Penguin History of Europe series. London: Allen Lane, 2007. __________. The Culture of Power and the Power of Culture: Old Regime Europe, 1660-1789. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. __________, editor. The Eighteenth Century: Europe 1688-1815. Short Oxford History of Europe series. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Bonney, Richard. The European Dynastic States, 1494-1660. The Short Oxford History of the Modern World series. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991. 1 Breunig, Charles and Matthew Levinger. The Revolutionary Era, 1789-1850. Norton History of Modern Europe series. Third edition. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2002. Bush, Michael L. Renaissance, Reformation and the Outer World, 1450-1660. Blandford History of Europe series. Second edition. London: Blandford Press, 1971. Cameron, Euan, editor. In Early Modern Europe: An Oxford History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.