Addressing E-Payment Challenges in Global E-Commerce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS PLASTIC DISAPPEARING? the Cards International Prepaid Summit

November 2015 Issue 525 www.cardsinternational.com IS PLASTIC DISAPPEARING? The Cards International Prepaid Summit • ANALYSIS: Card Fraud • INTERVIEW: ITRS • GUEST COMMENT: Peter Pop • COUNTRY REPORTS: Malaysia, China & Egypt CI Nov 525.indd 1 04/12/2015 14:40:17 Multichannel digital solutions for fi nancial services providers To fi nd out more about us please visit: www.intelligentenvironments.com Intelligent Environments is an international provider of innovative mobile and online solutions for fi nancial services providers. Our mission is to enable our clients to always stay close to their own customers. We do this through Interact®, our single software platform, which enables secure customer acquisition, engagement, transactions and servicing across any mobile and online channel and device. Today these are predominantly focused on smartphones, PCs and tablets. However Interact® will support other devices, if and when they become mainstream. We provide a more viable option to internally developed technology, enabling our clients with a fast route to market whilst providing the expertise to manage the complexity of multiple channels, devices and operating systems. Interact® is a continuously evolving technology that ensures our clients keep pace with the fast moving digital landscape. We are immensely proud of our achievements, in relation to our innovation, our thought leadership, our industrywide recognition, our demonstrable product differentiation, the diversity of our client base, and the calibre of our partners. For many years we have been the digital heart of a diverse range of fi nancial services providers including Atom Bank, Generali Wealth Management, HRG, Ikano Retail Finance, Lloyds Banking Group and Think Money Group. -

Moneylab Reader: an Intervention in Digital Economy

READER A N INTERVENTION IN DIGITAL ECONOMY FOREWORD BY SASKIA SASSEN EDITED BY GEERT LOVINK NATHANIEL TKACZ PATRICIA DE VRIES INC READER #10 MoneyLab Reader: An Intervention in Digital Economy Editors: Geert Lovink, Nathaniel Tkacz and Patricia de Vries Copy editing: Annie Goodner, Jess van Zyl, Matt Beros, Miriam Rasch and Morgan Currie Cover design: Content Context Design: Katja van Stiphout EPUB development: André Castro Printer: Drukkerij Tuijtel, Hardinxveld-Giessendam Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2015 ISBN: 978-90-822345-5-8 Contact Institute of Network Cultures phone: +31205951865 email: [email protected] web: www.networkcultures.org Order a copy or download this publication freely at: www.networkcultures.org/publications Join the MoneyLab mailing list at: http://listcultures.org/mailman/listinfo/moneylab_listcultures.org Supported by: Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (Hogeschool van Amster- dam), Amsterdam Creative Industries Publishing and the University of Warwick Thanks to everyone at INC, to all of the authors for their contributions, Annie Goodner and Morgan Currie for their copy editing, and to Amsterdam Creative Industries Publishing for their financial support. This publication is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. EDITED BY GEERT LOVINK, NATHANIEL TKACZ AND PATRICIA DE VRIES INC READER #10 Previously published INC Readers The INC Reader series is derived from conference contributions and produced by the Institute of Network Cultures. They are available in print, EPUB, and PDF form. The MoneyLab Reader is the tenth publication in the series. -

Defining the Digital Services Landscape for the Middle East

Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East 1 2 Contents Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East 4 The Digital Services landscape 6 Consumer needs landscape Digital Services landscape Digital ecosystem Digital capital Digital Services Maturity Cycle: Middle East 24 Investing in Digital Services in the Middle East 26 Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East 3 Defining the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East The Middle East is one of the fastest growing emerging markets in the world. As the region becomes more digitally connected, demand for Digital Services and technologies is also becoming more prominent. With the digital economy still in its infancy, it is unclear which global advances in Digital Services and technologies will be adopted by the Middle East and which require local development. In this context, identifying how, where and with whom to work with in this market can be very challenging. In our effort to broaden the discussion, we have prepared this report to define the Digital Services landscape for the Middle East, to help the region’s digital community in understanding and navigating through this complex and ever-changing space. Eng. Ayman Al Bannaw Today, we are witnessing an unprecedented change in the technology, media, and Chairman & CEO telecommunications industries. These changes, driven mainly by consumers, are taking Noortel place at a pace that is causing confusion, disruption and forcing convergence. This has created massive opportunities for Digital Services in the region, which has in turn led to certain industry players entering the space in an incoherent manner, for fear of losing their market share or missing the opportunities at hand. -

How Mpos Helps Food Trucks Keep up with Modern Customers

FEBRUARY 2019 How mPOS Helps Food Trucks Keep Up With Modern Customers How mPOS solutions Fiserv to acquire First Data How mPOS helps drive food truck supermarkets compete (News and Trends) vendors’ businesses (Deep Dive) 7 (Feature Story) 11 16 mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved TABLEOFCONTENTS 03 07 11 What’s Inside Feature Story News and Trends Customers demand smooth cross- Nhon Ma, co-founder and co-owner The latest mPOS industry headlines channel experiences, providers of Belgian waffle company Zinneken’s, push mPOS solutions in cash-scarce and Frank Sacchetti, CEO of Frosty Ice societies and First Data will be Cream, discuss the mPOS features that acquired power their food truck operations 16 23 181 Deep Dive Scorecard About Faced with fierce eTailer competition, The results are in. See the top Information on PYMNTS.com supermarkets are turning to customer- scorers and a provider directory and Mobeewave facing scan-and-go-apps or equipping featuring 314 players in the space, employees with handheld devices to including four additions. make purchasing more convenient and win new business ACKNOWLEDGMENT The mPOS Tracker™ was done in collaboration with Mobeewave, and PYMNTS is grateful for the company’s support and insight. PYMNTS.com retains full editorial control over the findings presented, as well as the methodology and data analysis. mPOS Tracker™ © 2019 PYMNTS.com All Rights Reserved February 2019 | 2 WHAT’S INSIDE Whether in store or online, catering to modern consumers means providing them with a unified retail experience. Consumers want to smoothly transition from online shopping to browsing a physical retail store, and 56 percent say they would be more likely to patronize a store that offered them a shared cart across channels. -

2019.05.10 Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Financial results briefing for the Q2 of FY2019 May 10, 2019 GMO Payment Gateway, Inc. st (Code: 3769, TSE-1 Section) h t t p s : //c o r p . g m o - pg. c o m / The Growth track record: KPIs & Business results FY2018 revenue reached ¥26.4bn and OP ¥6.5bn (unit: mil. JPY) (unit: mil. JPY) (unit: mil. JPY) *1 9,000 8,000 *2 30,000 Revenues Operating Profit EBITDA 26,417 8,000 7,516 7,000 6,550 25,000 7,000 +25.5% 6,000 +65.9% 6,000 +58.9% 20,000 5,000 5,000 15,000 4,000 4,000 3,000 3,000 10,000 2,000 2,000 5,000 1,000 1,000 0 0 0 2008/9 2009/9 2010/9 2011/9 2012/9 2013/9 2014/9 2015/9 2016/9 2017/9 2018/9 2008/9 2009/9 2010/9 2011/9 2012/9 2013/9 2014/9 2015/9 2016/9 2017/9 2018/9 2008/9 2009/9 2010/9 2011/9 2012/9 2013/9 2014/9 2015/9 2016/9 2017/9 2018/9 2019/9E 2019/9E 2019/9E J-GAAP IFRS J-GAAP IFRS J-GAAP IFRS Operating Stores*3 TRX Volume TRX Value 133,199 1.57 billion ¥4.1 trillion (*1)The group commenced voluntary adoption of IFRS in FY2018. The figures for the FY2017 have been re-calculated on the same basis. (*2)EBITDA under J-GAAP is calculated as the sum total of operating profit, depreciation and amortization; and under IFRST is calculated as sum total of operating profit and depreciation. -

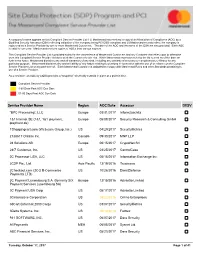

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

Middle East and Africa Online Payment Methods 2019 Publication Date: February 2019

MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA ONLINE PAYMENT METHODS 2019 PUBLICATION DATE: FEBRUARY 2019 PAGE 2 GENERAL INFORMATION I PAGE 3 KEY FINDINGS I PAGE 4-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS I PAGE 7 REPORT-SPECIFIC SAMPLE CHARTS I PAGE 8 METHODOLOGY I PAGE 9 RELATED REPORTS I PAGE 10 CLIENTS I PAGE 11-12 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS PAGE 13 ORDER FORM I PAGE 14 TERMS AND CONDITIONS MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA ONLINE PAYMENT METHODS 2019 PRODUCT DETAILS Title: Middle East and Africa Online Payment Methods 2019 Type of Product: Report Category: Online Payment Covered Regions: Middle East, Africa Covered Countries: UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Morocco, Lebanon, Bahrain, South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya, Tunisia, Namibia, Uganda Language: English Formats: PDF & PowerPoint Number of Charts: 87 PRICES* Single User License: € 1,950 (exc. VAT) Site License: € 2,925 (exc. VAT) Global Site License: € 3,900 (exc. VAT) We occasionally offer a discount on selected reports as newer reports are published. Please see the most up-to-date pricing on our website www.ystats.com. QUESTIONS What are the major digital payment trends in the Middle East and Africa? ANSWERED How do payment method preferences of online shoppers vary between countries? How high is the share of digital buyers using cash on delivery in various countries of the Middle IN THIS REPORT East and Africa? Which barriers prevent consumers from using online payments? What is the projected growth of mobile payments in the Middle East and Africa by 2022? SECONDARY MARKET Our reports are exclusively based on secondary market research. Our researchers derive RESEARCH information and data from a variety of reliable published sources and compile the data into understandable and easy-to-use formats. -

Services in Mena

A CONSUMER PERSPECTIVE OTT AND PREMIUM ONLINE VIDEO SERVICES IN MENA EXCLUSIVE REPORT FOR CABSAT now looking at this market seriously in INTRODUCTION order to drive new revenue streams as revenues from voice and SMS stagnate or even decline. The MENA region and in particular GCC markets have some of the highest In order to maximize a return on their internet penetration figures in the world investments it is important for operators and a proliferation of high end devices. to have a solid market understanding In parallel operators have invested from a consumer perspective on how heavily in fixed and mobile broadband OTT players have recognized this these developments are viewed. The services to be able to deliver high market opportunity and 2016 has size of the potential market, preferences quality experiences to customers. The seen the launch of new OTT services for premium content, willingness to distribution of video content in the in MENA for Premium Video Content. pay for premium, brand preferences, region has been dominated by satellite At the start of 2016 Netflix announced satisfaction with their experiences to TV operators to date. While the appetite global expansion to include MENA date and unmet needs. for video content is phenomenal with markets. The hyperbole around this Saudi Arabia famously having some launch raised the profile of OTT services, To this end Ipsos embarked on a of the highest per capita consumption other operators have followed suit with research programme to track market figures for online video anywhere in the Google Play movies launching towards developments from a customer view. -

Tokyo 100Ventures 101 Digital 11:FS 1982 Ventures 22Seven 2C2P

Who’s joining money’s BIGGEST CONVERSATION? @Tokyo ACI Worldwide Alawneh Exchange Apiture Association of National Advertisers 100Ventures Acton Capital Partners Alerus Financial AppBrilliance Atlantic Capital Bank 101 Digital Actvide AG Align Technology AppDome Atom Technologies 11:FS Acuminor AlixPartners AppFolio Audi 1982 Ventures Acuris ALLCARD INC. Appian AusPayNet 22seven Adobe Allevo Apple Authomate 2C2P Cash and Card Payment ADP Alliance Data Systems AppsFlyer Autodesk Processor Adyen Global Payments Alliant Credit Union Aprio Avant Money 500 Startups Aerospike Allianz Apruve Avantcard 57Blocks AEVI Allica Bank Limited Arbor Ventures Avantio 5Point Credit Union AFEX Altamont Capital Partners ARIIX Avast 5X Capital Affinipay Alterna Savings Arion bank AvidXchange 7 Seas Consultants Limited Affinity Federal Credit Union Altimetrik Arroweye Solutions Avinode A Cloud Guru Affirm Alto Global Processing Aruba Bank Aviva Aadhar Housing Finance Limited African Bank Altra Federal Credit Union Arvest Bank AXA Abercrombie & Kent Agmon & Co Alvarium Investments Asante Financial Services Group Axway ABN AMRO Bank AgUnity Amadeus Ascension Ventures AZB & Partners About Fraud AIG Japan Holdings Amazon Ascential Azlo Abto Software Aimbridge Hospitality American Bankers Association Asian Development Bank Bahrain Economic Development ACAMS Air New Zealand American Express AsiaPay Board Accenture Airbnb Amsterdam University of Applied Asignio Bain & Company Accepted Payments aircrex Sciences Aspen Capital Fund Ballard Spahr LLP Acciones y Valores -

Harnessing Internet Finance with Innovative Cyber Credit Management

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lin, Zhangxi; Whinston, Andrew B.; Fan, Shaokun Article Harnessing Internet finance with innovative cyber credit management Financial Innovation Provided in Cooperation with: SpringerOpen Suggested Citation: Lin, Zhangxi; Whinston, Andrew B.; Fan, Shaokun (2015) : Harnessing Internet finance with innovative cyber credit management, Financial Innovation, ISSN 2199-4730, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 1, Iss. 5, pp. 1-24, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40854-015-0004-7 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/176396 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Lin et al. Financial Innovation (2015) 1:5 DOI 10.1186/s40854-015-0004-7 RESEARCH Open Access Harnessing Internet finance with innovative cyber credit management Zhangxi Lin1,2*, Andrew B. -

IDC Finance Technology Conference 20 Ekim 2016

FinTech İstanbul Platformu Prof. Dr. Selim YAZICI Co-Founder FinTech Istanbul @SelimYazici IDC Finance Technology Conference 20 Ekim 2016 Nedir bu FinTech? Girişimcilik dünyasında 2014 yılından beri en çok duyulan kelime: “FinTech” Bankacılık Sigortacılık “Finansal HİZMET” sağlamak için “TEKNOLOJİ” kullanımı ! Aracı Kurumlar FinTech Neden Gündemde? Finans dünyasına, dijitalleşme ile çözüm: “Yeniden Yapılanma” Dijital kanallardan anında; hızlı esnek bireysel çözümler sunar FinTech Neden Gündemde? “Dijital Dönüşüm” Dijital kanallardan anında; hızlı esnek bireysel çözümler sunar FinTech Finansal Hizmetler Dünyasını Yeniden Şekillendirecek “Korkunun Ecele Faydası Yok” • Önümüzdeki 5 yıl içinde global FinTech yatırımlarının 150 Milyar USD’yi aşması bekleniyor. • FinTech’ler %100 müşteri odaklı • Müşterinin çektiği acıyı biliyorlar • Yeni iş modelleri ile yeni ürün ve hizmetleri getiriyorlar • FinTech Startupları geleneksel şirketlerin işlerini tehdit edebilir • Blockchain Teknolojisi çok şeyi değiştirecek Çözüm: “Rekaberlik” Dünyada FinTech Sadece Aralık 2015’de 81 FinTech girişimi 1 milyar USD yatırım aldı. 894 224 Sadece Google, son 5 yılda 37 farklı FinTech 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 yatırımı yaptı Son 5 yılda FinTech odaklı girişim sermayesi (VC) sayısı Dünyada FinTech Yatırımları DEsignED BY POWERED BY PIERRE DREUX Fintech Landscape Banking & Payment (356) Investments (108) Financing (196) Insurance (82) Banking (54) P2P Lending (49) Banking Personal Finance Investment P&C Reinsurance (6) Platforms Mobile Virtual Banking (9) - Expense -

Digital Payments: on Track to a Less-Cash Future

06 November 2019 SECTOR UPDATE INDIA INTERNET Digital Payments: On track to a less-cash future Digital Investment focus Key enablers - transactions to to shift from Payment gateways; reach USD 41tn wallets to other QR; POS by FY25 payment modes 6 November 2019 SECTOR UPDATE INDIA | INTERNET TABLE OF CONTENTS Prince Poddar [email protected] 03 Introduction Tel: (91 22) 62241879 04 Focus Charts 06 Fintech – attracting investments from global VCs Swapnil Potdukhe [email protected] 07 Payments industry in India Tel: (91 22) 62241876 09 Landscaping the digital payments industry 10 Sizing the digital payments market Pankaj Kapoor [email protected] 12 Digital payment infrastructure Tel: (91 22) 66303089 14 Pay-modes which enable digital payments 15 Business economics for digital payments enablers 17 Future of digital payments: Key themes • Evolving use-cases in digital payments • Positioning of payment gateway aggregators • POS deployment – government’s digital agenda • POS penetration to aid higher card transactions • UPI to lead the growth in digital payments • Will wallets be able to survive the onslaught of UPI? 26 Government’s smart initiatives for digital payments 28 Survey – online survey on digital payments 29 Funding of payments intermediaries in India 33 How are digital payments faring globally? 35 Takeaways from management meetings 36 Company Profiles 60 Appendix JM Financial Research is also available on: Bloomberg - JMFR <GO>, • How have the digital payments evolved in India? Thomson Publisher & Reuters • How card transaction processing works? S&P Capital IQ and FactSet and Visible Alpha Please see Appendix I at the end of this report for Important Disclosures and Disclaimers and Research Analyst Certification.