Robert G. Patterson, Partnership in the Gospel. from the Junkin's First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays ABSTRACT Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. In many ways it is the most striking example of that resurgence. Along with Roman Catholics, as of the 1950s Chinese Protestants carried the heavy historical liability of association with Western domi- nation or imperialism in China, yet they have not only overcome that inheritance but have achieved remarkable growth. Popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. This article first traces the gradual extension of interest in Chinese Protestants from Christian circles to the scholarly world during the last two decades, and then discusses salient characteristics of the Protestant movement today. These include its size and rate of growth, the role of Church–state relations, the continuing foreign legacy in some parts of the Church, the strong flavour of popular religion which suffuses Protestantism today, the discourse of Chinese intellectuals on Christianity, and Protestantism in the context of the rapid economic changes occurring in China, concluding with a perspective from world Christianity. Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. Today, on any given Sunday there are almost certainly more Protestants in church in China than in all of Europe.1 One recent thoughtful scholarly assessment characterizes Protestantism as “flourishing” though also “fractured” (organizationally) and “fragile” (due to limits on the social and cultural role of the Church).2 And popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Identity Tensions Among Chinese Intellectual Christians a Pa

“Who Am I”: Identity Tensions Among Chinese Intellectual Christians A paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion, San Francisco, California, August 14, 2004 Jianbo Huang Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Building 6, 27 Zhongguancun South Street Haidian, Beijing PR China 8610—88218477 [email protected] Since the Reform and Opening Up policy was implemented in 1978, a so-called tide of “Christianity Fever” has swept across the intellectual and academic circle. The concern and zeal they have for Christianity are reflected in the research, comments and translation of its history, theories, doctrines and persons, as well as stimulating the formation of the openness of recognizing Christianity afresh (or correctly). In this rising tide of Christianity in China, some intellectuals have accepted the “cross” and entered the hall of Christian belief including university students, teachers, writers, painters, scholars and scientists. Some overseas Chinese students had converted even earlier (Li, 1996). Obviously, Christianity has a special attraction for them. They were attracted by the doctrines and teachings, and /or personal eXposure to Christian fellowships, then converted and were baptized. Looking back on the beginning of the 20th century, it was also the intellectuals who started a vigorous “anti-Christian movement”, taking the chance of the May Fourth Movement in 1919 and the New Culture Movement, holding up the banners of “Mr. D” (democracy) and “Mr. S” (science). Generally speaking, they wanted to thrust Christianity aside because they assumed that religion equals superstition and was incompatible with science. They reasoned that science was a necessity if the life of the Chinese people was to be improved and China’s international status be promoted (Li, 1994:195-222). -

The Regeneration of Millennium Ancient City by Beijing-Hangzhou

TANG LEI, QIU JIANJUN, ‘FLOWING’: The Regeneration of Millennium ancient city , 47 th ISOCARP Congress 2011 ‘FLOWING’: The Regeneration of Millennium ancient city by Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal ——Practice in Suqian, Jiangsu, China 1 The Millennium ancient city - Suqian Overview 1.1 City Impression Suqian, A millennium ancient city in China, Great Xichu Conqueror Xiangyu's hometown, Birthplace of Chuhan culture, Layers of ancient cities buried. Yellow River (the National Mother River 5,464km) and Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (the National Wisdom River 1794km, declaring the World Cultural Heritage) run through it. With Luoma, Hongze Lake, it has "Two Rivers Two Lakes" unique spatial characteristics. Nowadays Suqian is meeting the challenge of leapfrog development and ‘Livable Cities’ transformation.The city area is 8555 square kilometers and the resident population is 4,725,100. In 2009 its GDP was RMB 82.685 billion, per capita GDP was RMB 1.75 million. It’s industrial structure is19.3:46.3:34.4, level of urbanization is 37.7% 1.2 Superiority Evaluation (1) industrial structure optimized continuously, overall strength increased significantly. (2) people's lives condition Improved. Urban residents per capita disposable income was 12000, increased 11.6% per year; Farmer’s per capita net income was 6,000, increased 8.9% per year. (3) City’s carrying capacity has improved significantly. infrastructure had remarkable results; the process of industrialization and urbanization process accelerated. (4) Good ecological environment. Good days for 331 days, good rate is 90.4%. (5) Profound historical accumulation. the ancient city, the birthplace of Chu and Han culture, the history of mankind living fossil 1.3 Development Opportunities (1) Expansion of the Yangtze River Delta. -

The Multiple Identities of the Nestorian Monk Mar Alopen: a Discussion on Diplomacy and Politics

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Introduction _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Introduction 37 Chapter 3 The Multiple Identities of the Nestorian Monk Mar Alopen: A Discussion on Diplomacy and Politics Daniel H.N. Yeung According to the Nestorian Stele inscriptions, in the ninth year of the Zhen- guan era of the Tang Dynasty (635 AD), the Nestorian monk Mar Alopen, carry- ing with him 530 sacred texts1 and accompanied by 21 priests from Persia, arrived at Chang’an after years of traveling along the ancient Silk Road.2 The Emperor’s chancellor, Duke3 Fang Xuanling, along with the court guard, wel- comed the guests from Persia on the western outskirts of Chang’an and led them to Emperor Taizong of Tang, whose full name was Li Shimin. Alopen en- joyed the Emperor’s hospitality and was granted access to the imperial palace library4, where he began to undertake the translation of the sacred texts he had 1 According to the record of “Zun jing 尊經 Venerated Scriptures” amended to the Tang Dynasty Nestorian text “In Praise of the Trinity,” there were a total of 530 Nestorian texts. Cf. Wu Changxing 吳昶興, Daqin jingjiao liuxing zhongguo bei: daqin jingjiao wenxian shiyi 大秦景 教流行中國碑 – 大秦景教文獻釋義 [Nestorian Stele: Interpretation of the Nestorian Text ] (Taiwan: Olive Publishing, 2015), 195. 2 The inscription on the Stele reads: “Observing the clear sky, he bore the true sacred books; beholding the direction of the winds, he braved difficulties and dangers.” “Observing the clear sky” and “beholding the direction of the wind” can be understood to mean that Alopen and his followers relied on the stars at night and the winds during the day to navigate. -

China Study Journal

CHINA STUDY JOURNAL CHINA DESK Churches Together in Britain and Ireland churches. ìogether IN BRITAIN ANO IREIAND® China Study Journal Spring/Summer 2011 Editorial Address: China Desk, Churches Together in Britain and Ireland, 39 Eccleston Square, London SW1V 1BX Email: [email protected] ISSN 0956-4314 Cover: Nial Smith Design, from: Shen Zhou (1427-1509), Poet on a Mountain Top, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Album leaf mounted as a hand scroll, ink and water colour on paper, silk mount, image 15 Vi x 23 % inches (38.74 x 60.33cm). © The Nelson-Arkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: Nelson Trust, 46-51/2. Photograph by Robert Newcombe. Layout by raspberryhmac - www.raspberryhmac.co.uk Contents Section I Articles 5 CASS work group Report on an in-house survey of Chinese 7 Christianity Caroline Fielder Meeting social need through charity: religious 27 contributions in China A new exploration of religious participation in 53 social services - a project research report on the Liaoning Province Catholic Social Service Center Gao Shining & He Guanghu The Central Problem of Christianity in Today's 71 China and some Proposed Solutions Section II Documentation 89 Managing Editor: Lawrence Braschi Translators: Caroline Fielder, Lawrence Braschi Abbreviations ANS : Amity News Service (HK) CASS : Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Beijing) CCBC : Chinese Catholic Bishops' Conference CCC : China Christian Council CCPA : Chinese Catholic Patriodc Association CM : China Muslim (Journal) CPPCC : Chinese People's Consultative Conference FY : Fa Yin (Journal of the Chinese Buddhist Assoc.) SCMP : South China Morning Post(HK) SE : Sunday Examiner (HK) TF : Tian Feng (Journal of the China Christian Council) TSPM : Three-Self Patriotic Movement UCAN : Union of Catholic Asian News ZENIT : Catholic News Agency ZGDJ : China Taoism (Journal) ZGTZJ : Catholic Church in China (Journal of Chinese Catholic Church) Note: the term lianghui is used in this journal to refer to the joint committees of the TSPM and CCC. -

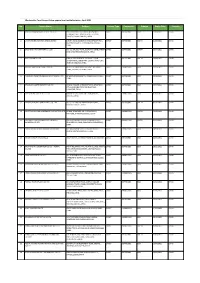

Apparel & Textile Factory List

Woolworths Food Group-Active apparel and textile factories- April 2021 No. Factory Name Address Factory Type Commodity Scheme Expiry Date Country 1 JIANGSU HONGMOFANG TEXTILE CO., LTD EAST CIFU ROAD, EAST RUISHENG AVENUE,, DIRECT SOFTGOODS BSCI 23/04/2021 CHINA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ZONE, SHUYANG COUNTY,,SUQIAN,JIANGSU,,CHINA 2 LIANYUNGANG ZHAOWEN SHOES LIMITED 2 BEIHAI ROAD,ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AREA, DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 11/05/2021 CHINA GUANNAN COUNTY,,LIANYUNGANG,JIANGSU,, CHINA 3 ZHUCHENG YIXIN GARMENT CO., LTD NO. 321 SHUNDU ROAD,,ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 13/07/2021 CHINA ZONE,,ZHUCHENG,SHANDONG,,CHINA 4 HRX FASHION CO LTD 1000 METERS SOUTH OF GUOCANG TOWN DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 25/08/2021 CHINA GOVERNMENT,,WENSHANG COUNTY, JINING CITY, JINING,SHANDONG,,CHINA 5 PUJIANG KINGSHOW CARPET CO LTD NO.75-1 ZHEN PU ROAD, PU JIANG, ZHE JIANG, DIRECT HARDGOODS BSCI 24/12/2021 CHINA CHINA,,PUJIANG,ZHEJIANG,,CHINA 6 YANGZHOU TENGYI SHOES MANUFACTURE CO., LTD. 13 WEST HONGCHENG RD,,,FANGXIANG,JIANGSU,, DIRECT SOFTGOODS BSCI 22/10/2021 CHINA CHINA 7 ZHAOYUAN CASTTE GARMENT CO LTD PANJIAJI VILLAGE, LINGLONG TOWN,,ZHAOYUAN DIRECT SOFTGOODS BSCI 06/07/2021 CHINA CITY, SHANDONG PROVINCE,ZHAOYUAN, SHANDONG,,CHINA 8 RUGAO HONGTAI TEXTILE CO LTD XINJIAN VILLAGE, JIANGAN TOWN,,RUGAO, DIRECT HARDGOODS BSCI 07/12/2021 CHINA JIANGSU,,CHINA 9 NANJING BIAOMEI HOMETEXTILES CO.,LTD NO.13 ERST WUCHU ROAD,HENGXI TOWN,,, DIRECT SOFTGOODS SMETA 04/11/2021 CHINA NANJING,JIANGSU,,CHINA 10 NANTONG YAOXING HOUSEWARE PRODUCTS CO.,LTD NO.999, TONGFUBEI RD., CHONGCHUAN, DIRECT HARDGOODS SMETA 24/09/2021 CHINA NANTONG,,NANTONG,JIANGSU,,CHINA 11 CHAOZHOU CHAOAN ZHENGYUN CERAMICS QIAO HU VILLAGE, CHAOAN, CHAOZHOU CITY, DIRECT HARDGOODS SMETA 19/05/2021 CHINA INDUSTRIAL CO LTD GUANGDONG, CHINA,,CHAOZHOU,GUANGDONG,, CHINA 12 YANTAI PACIFIC HOME FASHION FUSHAN MILL NO. -

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020 Wei Zhang Xiamen University Jia Rui Xiamen University Xiaoqing Cheng Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Bin Deng Xiamen University Hesong Zhang Xiamen University Lijing Huang Xiamen University Lexin Zhang Xiamen University Simiao Zuo Xiamen University Junru Li Xiamen University XingCheng Huang Xiamen University Yanhua Su Xiamen University Benhua Zhao Xiamen University Yan Niu Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing City, People’s Republic of China Hongwei Li Xiamen University Jian-li Hu Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Tianmu Chen ( [email protected] ) Page 1/30 Xiamen University Research Article Keywords: Hand foot mouth disease, Jiangsu Province, model, transmissibility, effective reproduction number Posted Date: July 30th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-752604/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/30 Abstract Background: Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has been a serious disease burden in the Asia Pacic region represented by China, and the transmission characteristics of HFMD in regions haven’t been clear. This study calculated the transmissibility of HFMD at county levels in Jiangsu Province, China, analyzed the differences of transmissibility and explored the reasons. Methods: We built susceptible-exposed-infectious-asymptomatic-removed (SEIAR) model for seasonal characteristics of HFMD, estimated effective reproduction number (Reff) by tting the incidence of HFMD in 97 counties of Jiangsu Province from 2015 to 2020, compared incidence rate and transmissibility in different counties by non -parametric test, rapid cluster analysis and rank-sum ratio. -

INTRODUCTION There Have Been Three Major Episodes of The

INTRODUCTION There have been three major episodes of the controversy on Confucian religiosity throughout Chinese intellectual history. The first episode started in the late 16th century with the Jesuit attempt to convert the Chinese population, and ended with the bitter twist of the Rites Controversy in the mid-18th century. Instead of seeing the sect of Literati as some form of paganism, the early Jesuits, Matteo Ricci in particular, tried to explore the compatibilities between Confucianism and Christianity from a pragmatic perspective. For them, Confucianism was nothing short of a preparation for the coming of Christianity to the Chinese land. It is through this historical encounter that Confucianism as a body of philosophy, beliefs, and rituals was systematically construed in Western societies. While the social and political conditions of the time did not allow the Jesuits to make much of headway, their effort to conciliate Confucianism with Christianity had set a long-lasting tone for modern imaginations about Confucianism and about religion in both Eastern and Western academic fields. The second surge of the controversy on Confucian religiosity took place during the late 19th and early 20th centuries when China was tremendously traumatized by social and political turmoil. Many Chinese intellectuals—traditionalists and iconoclasts alike— endeavored to capitalize on Confucianism for their political causes. While Kang Youwei and his followers tried to dress Confucianism up as a state religion to counter the influence of Christianity, the May Fourth intellectuals vehemently opposed any attempt of this kind. For the former, Confucianism is the gravity for the inspiration of Chinese national spirit just as Christianity is for Western societies; for the latter, Confucianism 1 belongs to the past and has to be swept into the realm of academics. -

The Growing Public Nature of Chinese Christianity

Edinburgh Research Explorer Chinese Public Theology Citation for published version: Chow, A 2018, Chinese Public Theology: Generational Shifts and Confucian Imagination in Chinese Christianity. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198808695.001.0001 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/oso/9780198808695.001.0001 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Introduction A state official once asked Confucius (551–479 BCE) about whether to kill all the wicked people in his domain. The sage replied, ‘Just desire the good yourself and the common people will be good. By nature the gentleman [junzi] is like wind and the small man [xiaoren] like grass. Let the wind sweep over the grass and it is sure to bend.’1 Confucius believed that morality is not limited to the private life but also has public implications. In context, he was teaching that the cultivation of a ruler’s moral character would result in a good and harmonious society. -

Study of the Allocation of Regional Flood Drainage Rights In

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Study of the Allocation of Regional Flood Drainage Rights in Watershed Based on Entropy Weight TOPSIS Model: A Case Study of the Jiangsu Section of the Huaihe River, China Kaize Zhang 1,2, Juqin Shen 3, Han Han 1,* and Jinglai Zhang 4 1 Business School, Hohai University, Nanjing 211100, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA 16802, USA 3 College of Agricultural Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemistry, College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Henan University, Kaifeng 475001, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 13 June 2020; Accepted: 10 July 2020; Published: 13 July 2020 Abstract: During the flood season, various regions in a watershed often have flood drainage conflicts, when the regions compete for flood drainage rights (FDR). In order to solve this problem, it is very necessary to study the allocation of FDR among various regions in the watershed. Firstly, this paper takes fairness, efficiency and sustainable development as the allocation principles, and comprehensively considers the differences of natural factors, social development factors, economic development factors and ecological environment factors in various regions. Then, an indicator system for allocation of FDR among regions in the watershed is established. Secondly, an entropy weight Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) model is used to construct the FDR allocation model among regions in the watershed. Based on a harmony evaluation model, a harmony evaluation and comparison are carried out on the FDR allocation schemes under three different allocation principles.