Final Chien and Wu Formatted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Primer on Governance Issues for China and Hong Kong

A Primer on Governance Issues for China and Hong Kong Michael DeGolyer October 2010 marks the 40th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian diplomatic relations with China. In recent years we usually think of China in terms of trade or currency issues or the potential impact of the booming Chinese economy. The political system is ignored as it is thought to be outside the western democratic tradition. This article looks at how modern China is dealing 2010 CanLIIDocs 256 with political forces arising from its increasingly capitalist economic system. It explains the very strong resistance to federalist theory although in some ways China seems headed toward a kind of de facto federalism. It suggests, particularly in the context of China-Hong Kong relations, we may be witnessing a new approach to governance which deserves to be better known among western states as they grapple with their own governance issues and as they try to come to terms with the emergence of China as a world power. entral authorities of the Peoples Republic Despite official denials that China practices any form of China are sensitive to even discussing of federalism, non-China based scholars such as Zheng Cfederalism. Those within China advocating Yongnian1 of the National University of Singapore federalism as a solution to China’s complex ethnic and may and do make the case for federalism in China. He regional relations have more than once run afoul of argues that in truth China governs itself behaviorally official suspicion that federalism is another name for as a de facto federalist state. -

No. 01: the Urban Food System of Nanjing, China

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Hungry Cities Partnership Reports and Papers 2016 No. 01: The Urban Food System of Nanjing, China Zhenzhong Si Balsillie School of International Affairs/WLU Jonathan Crush Balsillie School of International Affairs/WLU, [email protected] Steffanie Scott University of Waterloo Taiyang Zhong Nanjing University, China Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/hcp Part of the Food Studies Commons, Human Geography Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Si, Z., Crush, J., Scott, S., & Zhong, T. (2016). The Urban Food System of Nanjing, China (rep., pp. i-48). Waterloo, ON: Hungry Cities Partnership. Hungry Cities Report, No. 1. This Hungry Cities Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Reports and Papers at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hungry Cities Partnership by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUNGRY CITIES PARTNERSHIP T!" U#$%& F''( S)*+", '- N%&./&0, C!/&% HUNGRY CITIES REPORT NO. 1 HUNGRY CITIES PARTNERSHIP THE URBAN FOOD SYSTEM OF NANJING, CHINA ZHENZHONG SI WITH JONATHAN CRUSH, STEFFANIE SCOTT AND TAIYANG ZHONG SERIES EDITOR: PROF. JONATHAN CRUSH HUNGRY CITIES REPORT NO. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research and publication of this report was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and the Interna- tional Development Research Centre (IDRC) under the International Partnerships for Sustainable Societies (IPaSS) Program. © HUNGRY CITIES PARTNERSHIP 2016 Published by the Hungry Cities Partnership African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, South Africa, and Wilfrid Laurier University/Balsillie School of International Affairs, Waterloo, Canada First published 2016 ISBN 978-1-920597-16-0 Cover photo: Zhenzhong Si Production by Bronwen Dachs Muller, Cape Town All rights reserved. -

Nanjing Travel Guide - Page 1

Nanjing Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/nanjing page 1 Max: 32.5°C Min: 24.7°C Rain: 200.7mm Nanjing When To Aug Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Famed as 'The dwelling place of umbrella. Max: 31.6°C Min: 24.0°C Rain: 162.7mm tigers and dragons', Nanjing, a VISIT breathtakingly beautiful city, is Sep http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-nanjing-lp-1137867 dotted with hills and winding Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. waters. The city was the capital of Jan Max: 27.9°C Min: 19.3°C Rain: 62.6mm ancient China, famous for its Famous For : Places To VisitHistory & CulturCity Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, history and culture, and is currently umbrella. Oct Max: 7.1°C Min: -1.3°C Rain: 63.4mm Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, a real treat for history buffs. The umbrella. Capital of Jiangsu province, Nanjing is a city presents a pleasant picture of a Max: 22.7°C Min: 12.6°C Rain: 52.4mm famous historical and cultural city housing Feb great mix of ancient and modern many museums, tombs and historical sites. Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, umbrella. Nov cultures. For food-lovers, this place has a unique way Max: 9.8°C Min: 0.7°C Rain: 55.7mm Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, of cooking duck which has earned it one of umbrella. it’s many nicknames- Duck Capital. The rich Mar Max: 16.4°C Min: 5.9°C Rain: 57.4mm heritage combines with the natural scenic Very cold weather. -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends Over Pan-Arctic Tundra

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4229-4254; doi:10.3390/rs5094229 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra Uma S. Bhatt 1,*, Donald A. Walker 2, Martha K. Raynolds 2, Peter A. Bieniek 1,3, Howard E. Epstein 4, Josefino C. Comiso 5, Jorge E. Pinzon 6, Compton J. Tucker 6 and Igor V. Polyakov 3 1 Geophysical Institute, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, P.O. Box 757000, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.W.); [email protected] (M.K.R.) 3 International Arctic Research Center, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, 930 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, 291 McCormick Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Cryospheric Sciences Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Biospheric Science Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.E.P.); [email protected] (C.J.T.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-474-2662; Fax: +1-907-474-2473. -

Wu Guanzhong's Artistic Career Yong Zhang1,*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 572 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021) Wu Guanzhong's Artistic Career Yong Zhang1,* 1 State Specialist Institute of Arts, Rezervnyy Proyezd, D.12, Moscow, 121165 Russia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Combining with Wu Guanzhong's learning experience, this paper analyzes Chinese oil painting art characteristics in different periods, and the method of integrating traditional Chinese ink and wash painting language with the western modern design language in the aspects such as modelling, colour and composition. Wu Guanzhong successfully used western painting method to show the Oriental artistic conception, and formed unique composition views and forms. With the use of concise and simple colors and free-writing lines, the painter's personal emotions, thoughts and standpoint and deep understanding of life can be expressed. On the basis of in-depth research on the essence, connotation and thought of Chinese and Western art, Wu Guanzhong found the "junction" of the integration of Chinese and Western art. Keywords: Wu Guanzhong, Hangzhou Academy of Art, Ink and wash painting, Oil painting, Integration of Chinese and Western art. 1. INTRODUCTION Wu Guanzhong entered Hangzhou Academy of Art to study Chinese and Western paintings. In the Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), the People's school, he received direct guidance from teachers Artist, Art Educator, and Professor of the Academy such as Li Chaoshi, Fang Ganmin, and Pan of Arts and Design of Tsinghua University, used to Tianshou. Li Chaoshi and Fang Ganmin are both be an executive director of the Chinese Artists teachers who have returned from studying in Association, a member of the Standing Committee France, but their styles of painting are different. -

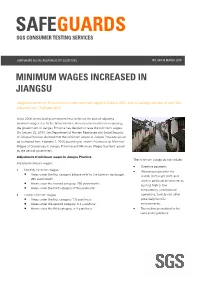

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

China Human Rights Report 2009

臺灣民主基金會 Taiwan Foundation for Democracy 本出版品係由財團法人臺灣民主基金會負責出版。臺灣民主基金會是 一個獨立、非營利的機構,其宗旨在促進臺灣以及全球民主、人權的 研究與發展。臺灣民主基金會成立於二○○三年,是亞洲第一個國家 級民主基金會,未來基金會志在與其他民主國家合作,促進全球新一 波的民主化。 This is a publication of the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD). The TFD is an independent, non-profit foundation dedicated to the study and promotion of democracy and human rights in Taiwan and abroad. Founded in 2003, the TFD is the first democracy assistance foundation established in Asia. The Foundation is committed to the vision of working together with other democracies, to advance a new wave of democratization worldwide. 本報告由臺灣民主基金會負責出版,報告內容不代表本會意見。 版權所有,非經本會事先書面同意,不得翻印、轉載及翻譯。 This report is published by the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy. Statements of fact or opinion appearing in this report do not imply endorsement by the publisher. All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the publisher. Taiwan Foundation for Democracy China Human Rights Report 2009 CONTENTS Foreword ....................................................................................................................i Chapter I: Preface ............................................................................................. 1 Chapter II: Social Rights .......................................................................... 25 Chapter III: Political Rights ................................................................... 39 Chapter IV: Judicial Rights ................................................................... -

Deciphering the Spatial Structures of City Networks in the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait Through the Lens of Functional and Innovation Networks

sustainability Article Deciphering the Spatial Structures of City Networks in the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait through the Lens of Functional and Innovation Networks Yan Ma * and Feng Xue School of Architecture and Urban-Rural Planning, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350108, Fujian, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 April 2019; Accepted: 21 May 2019; Published: 24 May 2019 Abstract: Globalization and the spread of information have made city networks more complex. The existing research on city network structures has usually focused on discussions of regional integration. With the development of interconnections among cities, however, the characterization of city network structures on a regional scale is limited in the ability to capture a network’s complexity. To improve this characterization, this study focused on network structures at both regional and local scales. Through the lens of function and innovation, we characterized the city network structure of the Economic Zone of the West Side of the Taiwan Strait through a social network analysis and a Fast Unfolding Community Detection algorithm. We found a significant imbalance in the innovation cooperation among cities in the region. When considering people flow, a multilevel spatial network structure had taken shape. Among cities with strong centrality, Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Whenzhou had a significant spillover effect, which meant the region was depolarizing. Quanzhou and Ganzhou had a significant siphon effect, which was unsustainable. Generally, urbanization in small and midsize cities was common. These findings provide support for government policy making. Keywords: city network; spatial organization; people flows; innovation network 1. -

Preventing Deglobalization: an Economic and Security Argument for Free Trade and Investment in ICT Sponsors

Preventing Deglobalization: An Economic and Security Argument for Free Trade and Investment in ICT Sponsors U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE FOUNDATION U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE CENTER FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION Contributing Authors The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is the world’s largest business federation representing the interests of more than 3 million businesses of all sizes, sectors, and regions, as well as state and local chambers and industry associations. Copyright © 2016 by the United States Chamber of Commerce. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form—print, electronic, or otherwise—without the express written permission of the publisher. Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 6 Part I: Risks of Balkanizing the ICT Industry Through Law and Regulation ........................................................................................ 11 A. Introduction ................................................................................................. 11 B. China ........................................................................................................... 14 1. Chinese Industrial Policy and the ICT Sector .................................. 14 a) “Informatizing” China’s Economy and Society: Early Efforts ...... 15 b) Bolstering Domestic ICT Capabilities in the 12th Five-Year Period and Beyond ................................................. 16 (1) 12th Five-Year -

Health Privatisation in China: from the Perspective of Subnational

Health Privatisation in China: from the Perspective of Subnational Governments By FENG Qian Submitted to Central European University Department of Political Science In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Anil Duman Budapest, Hungary 2020 Abstract From 2009, the Chinese government started to promote the policy She Hui Ban Yi/SHBY that encourages private investment in hospitals. This strategy of promoting private investment in hospitals represents the overall privatisation trend in Chinese health policymaking. Building on the national level health policymaking, the thesis focuses on the subnational governments in China and explains why are this national initiative has been implemented differently at the subnational level. Most existing studies in this topic focus either on the national level policymaking, discussing the relations between welfare policies and regime type or ideologies; or on the efficiency of public versus private hospitals in health sector by evaluating the outcomes. The thesis aims to understand SHBY and privatisation in health mainly from the local governments’ perspective, analysing how the fiscal survival pressure and political incentives affect the actual health policymaking in local governments in China. Drawing on official statistics, government policies and existing studies, the thesis mainly consider two types of influencing factors, and categorises three types of responses at the subnational levels. While the implementation of this policy requires a lot of resources and efforts, the thesis emphasises that, firstly, for the local governments, the fiscal impact, especially the hard budget constraint from the central government and soft budget constraint to the local public sector, plays the key role in health privatisation policies in China. -

The Regeneration of Millennium Ancient City by Beijing-Hangzhou

TANG LEI, QIU JIANJUN, ‘FLOWING’: The Regeneration of Millennium ancient city , 47 th ISOCARP Congress 2011 ‘FLOWING’: The Regeneration of Millennium ancient city by Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal ——Practice in Suqian, Jiangsu, China 1 The Millennium ancient city - Suqian Overview 1.1 City Impression Suqian, A millennium ancient city in China, Great Xichu Conqueror Xiangyu's hometown, Birthplace of Chuhan culture, Layers of ancient cities buried. Yellow River (the National Mother River 5,464km) and Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (the National Wisdom River 1794km, declaring the World Cultural Heritage) run through it. With Luoma, Hongze Lake, it has "Two Rivers Two Lakes" unique spatial characteristics. Nowadays Suqian is meeting the challenge of leapfrog development and ‘Livable Cities’ transformation.The city area is 8555 square kilometers and the resident population is 4,725,100. In 2009 its GDP was RMB 82.685 billion, per capita GDP was RMB 1.75 million. It’s industrial structure is19.3:46.3:34.4, level of urbanization is 37.7% 1.2 Superiority Evaluation (1) industrial structure optimized continuously, overall strength increased significantly. (2) people's lives condition Improved. Urban residents per capita disposable income was 12000, increased 11.6% per year; Farmer’s per capita net income was 6,000, increased 8.9% per year. (3) City’s carrying capacity has improved significantly. infrastructure had remarkable results; the process of industrialization and urbanization process accelerated. (4) Good ecological environment. Good days for 331 days, good rate is 90.4%. (5) Profound historical accumulation. the ancient city, the birthplace of Chu and Han culture, the history of mankind living fossil 1.3 Development Opportunities (1) Expansion of the Yangtze River Delta.