Miroslav Jovanović, Phd When We Speak Today About Both Present And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

£<5 T VV\V Rwve,___CONTINUED in JACKET Ssc Schvuulv Withlll

SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS. IjAÇKET^jj LEAGUE OF NATIONS. REGISTRY. r t Classement. , - - Jf)C\r Dossier N“ | 0^-vU ^), N' **>- Classement Document N". £<5 T_VV\V rwvE,____ SsC Schvuulv W ithlll REMETTRE CE DOCUMENT L'USAGE DE CET EMPLACEMENT EST remettre ce document (En second lieu). réservé au Registry. (En premier lieu). ■chedule within Document ) précédent i Index A. Index B. Schedule within Voir les dossiers : - A classer ' ' ' CONTINUED IN JACKET r rT « » % 1JACKET 3 Ï 1 9 2 a . % SOCIETE DES NATIONS. LEAGUE OF NATIONS. HF.GI8IRV. RUSSIAN REFUGEES Document No. I). -i.,r No. "T ... 2. 3 3 /<$/[ 22278 fîfy\< \£n.|iv d .C A O oM iZa 6 F 3x^{y* M • ^ (Kn I 'l'i-mitrr-Kcw.) (Kn Beuoinl-liini). Héeponaos, &c. (Out Letter Book) : C I'i tf&jXrZ' ^ " Ç/i^ __L J - a TRANSLATION of letter from M r .H A H N,Odessa to Mr Gorvin. t0* I6th November 1923. No.3554 A. Dear Mr Gorvin, A few days ago a small Italian steamer "ALLA" arrived here with about 300 Wrangel soldiers from Varna. About 80# of these refugees have been sent to their native country 'oy the Refugees Association, ^he journey from Varna to Odessa under very unfavourable conditions, costs 10 to 15 Turkish liras. These immigrants nave found here a shelter in the Feeding point of tfe Evacuation Authorities, but they are isolated. They get I pound bread per day, some soup (meat every two days) andbgruel for supper. They are examined as to their state of health and undergo treatment where necessary. -

The Production of Lexical Tone in Croatian

The production of lexical tone in Croatian Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie im Fachbereich Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität zu Frankfurt am Main vorgelegt von Jevgenij Zintchenko Jurlina aus Kiew 2018 (Einreichungsjahr) 2019 (Erscheinungsjahr) 1. Gutacher: Prof. Dr. Henning Reetz 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Sven Grawunder Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 01.11.2018 ABSTRACT Jevgenij Zintchenko Jurlina: The production of lexical tone in Croatian (Under the direction of Prof. Dr. Henning Reetz and Prof. Dr. Sven Grawunder) This dissertation is an investigation of pitch accent, or lexical tone, in standard Croatian. The first chapter presents an in-depth overview of the history of the Croatian language, its relationship to Serbo-Croatian, its dialect groups and pronunciation variants, and general phonology. The second chapter explains the difference between various types of prosodic prominence and describes systems of pitch accent in various languages from different parts of the world: Yucatec Maya, Lithuanian and Limburgian. Following is a detailed account of the history of tone in Serbo-Croatian and Croatian, the specifics of its tonal system, intonational phonology and finally, a review of the most prominent phonetic investigations of tone in that language. The focal point of this dissertation is a production experiment, in which ten native speakers of Croatian from the region of Slavonia were recorded. The material recorded included a diverse selection of monosyllabic, bisyllabic, trisyllabic and quadrisyllabic words, containing all four accents of standard Croatian: short falling, long falling, short rising and long rising. Each target word was spoken in initial, medial and final positions of natural Croatian sentences. -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

The Ethno-Cultural Belongingness of Aromanians, Vlachs, Catholics, and Lipovans/Old Believers in Romania and Bulgaria (1990–2012)

CULTURĂ ŞI IDENTITATE NAŢIONALĂ THE ETHNO-CULTURAL BELONGINGNESS OF AROMANIANS, VLACHS, CATHOLICS, AND LIPOVANS/OLD BELIEVERS IN ROMANIA AND BULGARIA (1990–2012) MARIN CONSTANTIN∗ ABSTRACT This study is conceived as a historical and ethnographic contextualization of ethno-linguistic groups in contemporary Southeastern Europe, with a comparative approach of several transborder communities from Romania and Bulgaria (Aromanians, Catholics, Lipovans/Old Believers, and Vlachs), between 1990 and 2012. I am mainly interested in (1) presenting the ethno-demographic situation and geographic distribution of ethnic groups in Romania and Bulgaria, (2) repertorying the cultural traits characteristic for homonymous ethnic groups in the two countries, and (3) synthesizing the theoretical data of current anthropological literature on the ethno-cultural variability in Southeastern Europe. In essence, my methodology compares the ethno-demographic evolution in Romania and Bulgaria (192–2011), within the legislative framework of the two countries, to map afterward the distribution of ethnic groups across Romanian and Bulgarian regions. It is on such a ground that the ethnic characters will next be interpreted as either homologous between ethno-linguistic communities bearing identical or similar ethnonyms in both countries, or as interethnic analogies due to migration, coexistence, and acculturation among the same groups, while living in common or neighboring geographical areas. Keywords: ethnic characters, ethno-linguistic communities, cultural belongingness, -

The Influence of External Actors in the Western Balkans

The influence of external actors in the Western Balkans A map of geopolitical players www.kas.de Impressum Contact: Florian C. Feyerabend Desk Officer for Southeast Europe/Western Balkans European and International Cooperation Europe/North America team Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Phone: +49 30 26996-3539 E-mail: [email protected] Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. 2018, Sankt Augustin/Berlin Maps: kartoxjm, fotolia Design: yellow too, Pasiek Horntrich GbR Typesetting: Janine Höhle, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Diese Publikation ist/DThe text of this publication is published under a Creative Commons license: “Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 international” (CC BY-SA 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/4.0/legalcode. ISBN 978-3-95721-471-3 Contents Introduction: The role of external actors in the Western Balkans 4 Albania 9 Bosnia and Herzegovina 14 Kosovo 17 Croatia 21 Macedonia 25 Romania 29 Serbia and Montenegro 32 The geopolitical context 39 3 Introduction: The role of external actors in the Western Balkans by Dr Lars Hänsel and Florian C. Feyerabend Dear readers, A spectre haunts the Western Balkans – the spec- consists of reports from our representatives in the tre of geopolitics. Once again, the region is at risk various countries involved. Along with the non-EU of becoming a geostrategic chessboard for exter- countries in the Western Balkans, this study also nal actors. Warnings are increasingly being voiced considers the situation in Croatia and Romania. in Brussels and other Western capitals, as well as in the region itself. Russia, China, Turkey and the One thing is clear: the integration of the Western Gulf States are ramping up their political, eco- Balkans into Euro-Atlantic and European struc- nomic and cultural influence in this enclave within tures is already well advanced, with close ties and the European Union – with a variety of resources, interdependencies. -

Cinema / Performance Program

Cinema / Performance Program Soviet cinema of the 1920s and after introduced Il cinema sovietico degli anni ’20 e successivi or popularized significant new genres and subjects: introdusse e rese popolari nuovi significativi generi agitational newsreels, educational shorts, and e soggetti: cinegiornali di protesta, cortometraggi documentaries on mass cultural events or the educativi e documentari su eventi culturali di massa everyday lives of urban or agricultural workers, o sulla vita di tutti i giorni dei lavoratori di città o among others. Trains and village tents became agricoli. Treni e tendoni diventarono case di cinema makeshift movie houses; in artists’ imagination, improvvisati; nell’immaginario degli artisti, chioschi multimedia kiosks would soon spring up on street multimediali sarebbero comparsi agli angoli delle corners across the USSR. The aim was to open a strade in tutta l’USSR. L’obbiettivo era quello di aprire vast, heterogeneous populace to new ideas and una vasta ed eterogenea popolazione a nuove idee e technologies and in doing so to shape tecnologie e così formare il vero popolo sovietico. a truly Soviet people. A metà del ventesimo secolo l’Unione Sovietica The Soviet Union inspired new systems of è stata di ispirazione per la nascita di nuovi sistemi governance across the world in the mid-twentieth governativi in tutto il mondo, quando gli imperi century, when Western colonial empires fell and coloniali occidentali decaddero e la Russia e gli Stati Russia and the United States battled for international Uniti combatterono -

Serbia & Montenegro

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SERBIA & MONTENEGRO Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 27 September, 2005) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin de Balexert, 7-9 1219 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 799 07 00 Fax: + 41 22 799 07 01 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 8 IDPS FROM KOSOVO: STUCK BETWEEN UNCERTAIN RETURN PROSPECTS AND DENIAL OF LOCAL INTEGRATION 8 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND 12 BACKGROUND 12 THE CONFLICT IN KOSOVO (1981-1999): INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY FINALLY IMPOSES AUTONOMY OF THE PROVINCE TO YUGOSLAV AUTHORITIES 12 OUSTING OF PRESIDENT MILOSEVIC OPENS NEW ERA OF DEMOCRACY (2000-2003) 14 DJINDJIC ASSASSINATION THREATENS CONTINUATION OF SERBIA’S REFORMS (2003) 15 KOSOVO UNDER INTERNATIONAL ADMINISTRATION (2003) 16 BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT IN SOUTHERN SERBIA (2000-2005) 18 UNCERTAINTY AROUND FINAL STATUS ISSUE HAS A NEGATIVE IMPACT ON DISPLACEMENT AND RETURN (2005) 21 CAUSES OF DISPLACEMENT 23 DISPLACEMENT BEFORE AND DURING NATO INTERVENTION (1998-1999) 23 MASSIVE RETURN OF KOSOVO ALBANIANS SINCE END OF NATO INTERVENTION (FROM JUNE 1999) 26 LARGE SCALE DISPLACEMENT OF ETHNIC MINORITIES FOLLOWING THE NATO INTERVENTION (1999) 26 DISPLACEMENT CAUSED BY -

Yugosphere Tim Judah

LSEE Papers on South Eastern Europe Tim Judah Good news from the Western Balkans YUGOSLAVIA IS DEAD LONG LIVE THE YUGOSPHERE TIM JUDAH Tim Judah Good news from the Western Balkans YUGOSLAVIA IS DEAD LONG LIVE THE YUGOSPHERE TIM JUDAH Yugoslavia is Dead . Long Live the Yugosphere LSEE – Research on South Eastern Europe European Institute, LSE Edited by Spyros Economides Managing Editor Ivan Kovanović Reproduction and Printing Crowes Complete Print, London, November 2009 Design & Layout Komshe d.o.o. Cover Photograph Tim Judah Tim Judah LSEE Papers LSEE, the LSE’s new research unit on South East Europe, wel- comes you to the first of the LSEE Papers series. As part of the ac- tivities of LSEE we aim to publish topical, provocative and timely Papers, alongside our other core activities of academic research and public events. As part of our commitment to quality and impact we will commission contributions from eminent commentators and policy-makers on the significant issues of the day pertaining to an ever-important region of Europe. Of course, independent submissions will also be considered for the LSEE Paper series. It is with great pleasure that the LSEE Papers are launched by a hugely stimulating contribution from Tim Judah whose knowledge and expertise of the region is second to none. Tim Judah worked on this paper while with the LSE as a Senior Visiting Fellow in 2009 and we are delighted to inaugurate the series with his work on the ‘Yugosphere’. Dr Spyros Economides Yugoslavia is Dead . Long Live the Yugosphere Tim Judah v Tim Judah Preface In general terms good news is no news. -

The Relationship Between Space, Resources, and Genocide

Ruling the Bloodlands: The Relationship between Space, Resources, and Genocide Connor Mayes Advisor: Dr. Kari Jensen, Department of Global Studies & Geography Committee: Dr. Zilkia Janer, Department of Global Studies & Geography, and Dr. Mario Ruiz, Department of History Honors Essay in Geography Fall 2017 Hofstra University Mayes 2 Contents Part 1: The Meaning of Genocide................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Positionality and Purpose ......................................................................................................... 5 Definitions: Genocide, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, and war crimes .......... 6 Part 2: Genocide and Resources ................................................................................................ 10 Material Murder: The Link between Genocide and Resources ......................................... 10 Land .......................................................................................................................................... 13 Natural Resources ................................................................................................................... 19 Human Resources .................................................................................................................... 25 Cultural and Urban Resources ............................................................................................. -

The Deterritorialised Muslim Convert in Post-Communist Eastern European Cinema

BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2014 / VOLUME 2 / ARTICLE Article The Deterritorialised Muslim Convert in Post-Communist Eastern European Cinema EWA MAZIERSKA, University of Central Lancashire, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] LARS KRISTENSEN, University of Skövde, Sweden; email: [email protected] EVA NÄRIPEA, Estonian Academy of Arts, Film Archives of The National Archives; email: [email protected] 54 DOI: 10.1515/bsmr-2015-0015 BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2014 / VOLUME 2 / ARTICLE ABSTRACT This article analyses the Muslim convert as portrayed in three post-communist Eastern European fi lms: Vladimir Khotinenko’s A Moslem (Мусульманин, Russia, 1996), Jerzy Skolimowski’s Essential Killing (Poland/Norway/ Ireland/Hungary/France, 2010), and Sulev Keedus’s Letters to Angel (Kirjad Inglile, Estonia, 2011). Although set in diff erent periods, the fi lms have their origins in Afghanistan and then move to European countries. The conversion to Islam happens in connection to, or as a con- sequence of, diff erent military confl icts that the country has seen. The authors examine the consequences the char- acters have on their environment, using Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of deterritorialisation, under- stood as an opportunity to produce political and cultural change. Resettling from one religion and place into another means breaking up structures that need to be reassembled diff erently. However, these three fi lms seem to desire deterritorialisation and resettlement for diff erent reasons. In A Moslem, national structures need to be reset since foreign Western values have corrupted the post-com- munist Russian rural society. In Essential Killing, it is the Western military system of oppression that cannot uphold the convert and his values. -

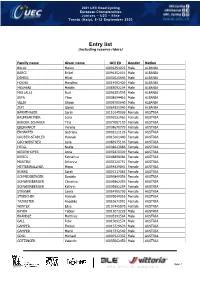

Entry List (Including Reserve Riders)

2021 UEC Road Cycling European Championships Juniors – U23 – Elite Trento (Italy), 8-12 September 2021 Entry list (including reserve riders) Family name Given name UCI ID Gender Nation BALAJ Mateo 10096354023 Male ALBANIA BARCI Brikel 10096352003 Male ALBANIA DEMIRI Mikel 10032025643 Male ALBANIA HOXHA Marolino 10014592420 Male ALBANIA MALHANI Mejdin 10083092204 Male ALBANIA MULLALLI Nuri 10096351595 Male ALBANIA SEFA Ylber 10008694416 Male ALBANIA VELIA Olsian 10009705640 Male ALBANIA ZEFI Gjergj 10064821040 Male ALBANIA BÄRNTHALER Sarah 10110145096 Female AUSTRIA BAUMGARTNER Lena 10096522963 Female AUSTRIA BERGER-SCHAUER Tina 10077087193 Female AUSTRIA EBERHARDT Verena 10008670770 Female AUSTRIA ERHARTER Gabriela 10092222126 Female AUSTRIA GRUBER-STADLER Hannah 10015661440 Female AUSTRIA GSCHWENTNER Leila 10083975106 Female AUSTRIA HEIGL Nadja 10008623886 Female AUSTRIA KIESENHOFER Anna 10092870309 Female AUSTRIA KREIDL Katharina 10048898084 Female AUSTRIA MARTINI Johanna 10035120751 Female AUSTRIA MITTERWALLNER Mona 10054839841 Female AUSTRIA RIJKES Sarah 10007217083 Female AUSTRIA SCHMIDSBERGER Daniela 10099849356 Female AUSTRIA SCHWEINBERGER Christina 10009862355 Female AUSTRIA SCHWEINBERGER Kathrin 10009862254 Female AUSTRIA STIGGER Laura 10054955736 Female AUSTRIA STREICHER Hannah 10035049316 Female AUSTRIA TAZREITER Angelika 10010671091 Female AUSTRIA WINTER Elisa 10107445870 Female AUSTRIA BAYER Tobias 10011072229 Male AUSTRIA BRÄNDLE Matthias 10005391564 Male AUSTRIA GALL Felix 10015092574 Male AUSTRIA GAMPER Florian 10015329620 -

The Charlotte Zolotow Award Observations About Publishing in 1998

CCBC Choices Kathleen T. Horning Ginny Moore Kruse Megan Schliesman Cooperative Children's Book Center School of Education University of Wisconsin-Madison Copyright 01999, Friends of the CCBC, Inc. (ISBN 0-931641-98-5) CCBC Choices was produced by University Publications, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Cover design: Lois Ehlert For information about other CCBC publications, send a self- addressed, stamped envelope to: Cooperative Children's Book Cenrer, 4290 Helen C. White Hall, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 600 N. Park St., Madison, WI 53706-1403 USA. Inquiries may also be made via fax (6081262-4933) or e-mail ([email protected]).See the World Wide Web (http://www.soemadison.wisc.edu/ccbc/)for information about CCBC publications and the Cooperative Children's Book Center. Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Results of the CCBC Award Discussions The Charlotte Zolotow Award Observations about Publishing in 1998 The Choices The Natural World Seasons and Celebrations Folklore, Mythology and Traditional Literature Historical People, Places and Events Biography 1 Autobiography Contemporary People, Places and Events Issues in Today's World Understanding Oneself and Others The Arts Poetry Concept Books Board Books Picture Books for Younger Children Picture Books for Older Children Easy Fiction Fiction for Children Fiction for Teenagers New Editions of Old Favorites Appendices Appendix I: How to Obtain the Books in CCBC Choices and CCBC Publications Appendix 11: The Cooperative Children's Book Center (CCBC) Appendix 111: CCBC Book Discussion Guidelines Appendix IV: The Compilers of CCBC Choices 1998 Appendix V:The Friends of the CCBC, Inc. Index CCBC Choices 1778 5 Acknowledgments Thank you to Friends of the CCBC member Tana Elias for creating the index for this edition of CCBC Choices.