Digra Conference Publication Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bar Code Printing Guide

Bar Code Printing Guide Please read this guide before operating this product. After you finish reading this guide, store it in a safe place for future reference. ENG Bar Code Printing Guide How This Manual is Organized Chapter 1 Before You Start Chapter 2 Getting Started Chapter 3 Bar Code Symbols and Formats Chapter 4 Troubleshooting Chapter 5 Appendix Considerable effort has been made to ensure that this manual is free of inaccuracies and omissions. However, as we are constantly improving our products, if you need an exact specification, please contact Canon. Contents Preface . vi How To Use This Manual . vi Symbols Used in This Manual . vi Abbreviations Used in This Manual . vi Legal Notices . vii Licence Notice . .vii Trademarks . .vii Copyright . .vii Disclaimers . viii Chapter 1 Before You Start Introduction . 1-2 Overview of Bar Codes . 1-2 1D Bar Codes . 1-2 2D Bar Codes . 1-2 Product Features . 1-2 Menus and Their Functions . 1-3 Accessing the Menus. 1-3 BarDIMM Menu . 1-3 FreeScape Menu . 1-4 Chapter 2 Getting Started Building/Printing a Bar Code . 2-2 Building a Bar Code. 2-2 Printing a Bar Code . 2-3 Cursor Position. 2-3 Transparent Print Data Mode . 2-3 Presentation. 2-4 Bar Code Readability. 2-4 Control Codes . 2-5 PCL Escape Sequences . 2-5 Bar Code Rotation Codes . 2-5 Font Switching . 2-6 OCR-A and OCR-B Fonts . 2-6 FreeScape Codes . 2-7 iii Chapter 3 Bar Code Symbols and Formats Font Parameters. .3-2 T Parameter . .3-2 p Parameter . -

Visual Design in Video Games

Forthcoming in WOLF, Mark J.P. (ed.). Video Game History: From Bouncing Blocks to a Global Industry, Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. Visual Design in Video Games Carl Therrien So why did polygons become the ubiquitous virtual bricks of videogames? Because, whatever the interesting or eccentric devices that had been thrown up along the way, videogames, as with the strain of Western art from the Renaissance up until the shock of photography, were hell-bent on refining their powers of illusionistic deception. —Stephen Poole (2000, page 125). Illusion refining, indeed, appears to be a major driving force of video game evolution. The appeal of ever-more realistic depictions of virtual universes in itself justifies the purchase of expensive new machinery, be it the latest console or dedicated computer parts. Yet, one must not conceive of this evolution as a linear progression towards perfect verisimilitude. The relative quality of static and dynamic renders, associated with a wide range of imaging techniques more or less suited to the capabilities of any given video game system, demonstrate the unsteady evolution of visual representation in the short history of the medium. Moreover, older techniques are sometimes integrated in the latest 3-D games, and 2-D gaming still enjoys a very strong following with portable game systems. Despite its short history, a detailed account of the apparatus behind the illusion would already require many volumes in itself. In this chapter, we will examine only the fundamentals of the different imaging techniques along with key examples. However, we hope to go further than a simple historical account of illusion refining, and expose the different ideals that governed and still governs the evolution of visual design in games. -

Great Northern Machine Wars: Rivalry Between User Groups in Finland

Great Northern Machine Wars: Rivalry Between User Groups in Finland Petri Saarikoski University of Turku, Finland Markku Reunanen Aalto University School of Arts, Design, and Architecture, Finland The history of computing has been colored by “computer wars” that have raged between competing companies. Although the commercial wars have received much attention, clashes between supporters of different platforms remain largely undocumented. This article approaches the topic from a Finnish hobbyist perspective, focusing on three case studies that range from the emergence of affordable home computers and videogame consoles to modern-day wars. Home computer culture has always been different things to the participants. Most marked by a rivalry of user groups. A typical notably, the grassroots wars are often emo- confrontation takes place between the user tionally loaded, personal, and local. The groups of two competing computer models, “flame wars” taking place in social media such as the competition between PC and share several traits with the machine wars.3 It Apple Macintosh users. Another well-known would be an oversimplification to claim that case is the struggle of Linux operating system the users are fighting for the companies users against Microsoft Windows users start- because their motives are much more com- ing in the 1990s. In addition to computing plex than that. So far, most publications have platforms, there have been battles between focused on the commercial side of things and the users of videogame consoles, games (for in only a few countries,4 such as the United example, Super Mario versus Sonic the States or UK, creating a knowledge gap con- Hedgehog), and even hardware extensions. -

Desarrollo De Un Prototipo De Videojuego

UNIVERSIDAD DE EXTREMADURA Escuela Politécnica Máster en Ingeniería Informática Trabajo de Fin de Máster Desarrollo de un Prototipo de Videojuego Ricardo Franco Martín Noviembre, 2016 UNIVERSIDAD DE EXTREMADURA Escuela Politécnica Máster en Ingeniería Informática Trabajo de Fin de Máster Desarrollo de un Prototipo de Videojuego Autor: Ricardo Franco Martín Fdo: Directores: Pablo García Rodriguez y Rober Morales Chaparro Fdo: Tribunal Calicador Presidente: Fdo: Secretario: Fdo: Vocal: Fdo: Dedicado a mi familia i ii Agradecimientos Quisiera agradecer a varias personas el apoyo y ayuda que me han prestado en la realización de este Trabajo de Fin de Máster. En primer lugar, agradecer a mi director Pablo García Rodríguez por per- mitirme realizar este proyecto y recibirme con los brazos abiertos cada vez que he necesitado su ayuda. También quiero agradecer a mi codirector Rober Morales Chaparro por conar en mí y proporcionarme una de las fases profesional y educativa más importantes de mi vida. Por último, agradecer a mi familia y amigos, que sin su apoyo, no habría llegado tan lejos. En especial, darle las gracias a mi hermano José Carlos Franco Martín que ha realizado y proporcionado algunos recursos artísticos para el proyecto. ½Muchas gracias a todos! iii iv Resumen Este Trabajo de Fin de Máster (en adelante TFM) trata sobre todo el proceso de investigación, conguración de un entorno de trabajo y desarrollo de un prototipo de videojuego. Analizaremos la tecnología actual y repasaremos algunas de las herramien- tas más relevantes utilizadas en el proceso de desarrollo de un videojuego. Seguidamente, trataremos de desarrollar un videojuego. Para ello, a partir de una idea de juego, diseñaremos las mecánicas y construiremos un prototipo funcional que pueda ser jugado y que reeje las principales características planteadas en la idea inicial, con el objetivo de comprobar si el juego es viable, si es divertido y si interesa desarrollar el juego completo. -

Pelit-Lehden Lukijakirjeet [email protected] Ja Digipelaamisen Muutos Suomessa Vuosina 1992–2002 Turun Yliopisto

Pelitutkimuksen vuosikirja 2012, s. 21–40. Toim. Jaakko Suominen et al. Tampereen yliopisto. http://www.pelitutkimus.fi Artikkeli PETRI SAARIKOSKI “Rakas Pelit-lehden toimitus...” Pelit-lehden lukijakirjeet [email protected] Turun yliopisto ja digipelaamisen muutos Suomessa vuosina 1992–2002 Tiivistelmä Readers’ letters in Finnish Pelit gaming magazine during Artikkelissa tarkastellaan lukijakirjeiden roolia Pelit-lehdessä vuosina 1992–2002. Aineisto 1992–2002 tarjoaa ainutkertaisen aikalaiskuvan suomalaisesta pelikulttuurista. Kyseisenä ajanjakso- na Suomessa PC oli tärkein pelikone kotitalouksissa, konsolien merkitys alkoi näkyä vasta Abstract tarkasteltavan ajanjakson loppupuolella. Kirjeissä pelaajat ottivat yleensä kantaa lehdessä Article examines the history of readers’ letters in Finnish Pelit computer game magazine julkaistuihin juttuihin tai muihin pelimaailman ajankohtaisiin ilmiöihin ja tapahtumiin. during 1992–2002. Letters provides a unique picture of the Finnish game culture in time Niissä kyseltiin myös paljon pelaamisen liittyviä vinkkejä ja vihjeitä. Osa kirjeistä voidaan when PC was the most popular game machine in Finland. The importance of game con- luokitella niin sanotuiksi “fanikirjeiksi”, joissa lukijat jakoivat kehuja lehden tunnetuille soles, such as Sony Play Station, began to emerge from late 1990s onwards. In the letters peliarvostelijoille. Kirjeissä näkyy miten tietoverkot, aluksi BBS-purkit ja myöhemmin players gave their opinions of the published game reviews or commented on the contem- Internet, alkoivat vakiinnuttaa asemaansa pelaajia yhdistävinä viestintävälineinä, mikä porary issues and events in gaming culture. They also asked for a gaming tips and tricks. lopulta näkyi myös postitettujen kirjeiden määrän romahtamisena vuodesta 1997 eteen- Some of the letters could be classified as so-called “fan letters”, where readers shared their päin. praise for the well-known game reviewers. -

3Dckit-Alt-Manual

30 conSTRUCTIOn Hll C64, SPECTRUM & AMSTRAD CPC CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 REGISTRATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 LOADING INSTRUCTIONS 3 INTRODUCTION TO FREESCAPE 6 INTRODUCTION TO THE EDITOR 11 THE USER INTERFACE 13 MOVEMENT AND VIEWPOINT CONTROLS 15 THE 3D KIT GAME 16 CREATING AND EDITING YOUR FIRST OBJECT 16 FILE MENU OPTIONS 17 GENERAL MENU OPTIONS 18 AREA MENU OPTIONS 21 CONDITION MENU OPTIONS 23 THE SHORTCUT ICONS 24 CONDITIONS - FREESCAPE COMMAND LANGUAGE (FCL) 28 EXAMPLES 41 VARIABLES - HOW TO USE VARIABLES 42 HANDLING VALUES GREATER THAN 255 43 APPENDIX 45 INTRODUCTION Manual by: Mandy Rodrigues Welcome to the 3D Construction Kit. We had often been asked when a Freescape Typesetting : Peter Carter of Starlight Graphics creator would be made, so here it is! It represents a total of four and a half years of Additional contributions : Andy Tait actual development, and many more man-years. Helen Andrew The program uses an advanced version of the Freescape 3D System, and will Anita Bradley allow you to design and create your own 3D Virtual Worlds. These could be your living Ursula Taylor room, your office, an ideal home or even a space station ! Thanks also to: Domark Software You may then walk or fly through the three dimensional environment as if you (j ii 3:f'(tf.U; '" is a registered trademark of Incentive Software . were actually there. Look around, up and down, move forward and back, go inside Program and documentation copyright © 1991 . New D1mens1on International buildings and even interact with objects you find. The facilities to make a fully fledged Limited, Zephyr One, Calleva Park, Aldermaston , Berkshire RG7 4QW. -

Kalle Kotipsykiatri -Tietokone- Ohjelma Tekoälyn Popularisoijana 1980-Luvulla

THS Tekniikan Waiheita ISSN 2490-0443 Tekniikan Historian Seura ry. 37. vuosikerta:3 2019 https://journal.fi/tekniikanwaiheita ”Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa”: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokone- ohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen Jaakko Suominen https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1352-7699 To cite this article: Petri Saarikoski, Markku Reunanen & Jaakko Suominen, ”'Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa': Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokoneohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-lu- vulla” Tekniikan Waiheita 37, no. 3 (2019): 6–30. https://dx.doi.org/10.33355/tw.86772 To link to this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.33355/tw.86772 ”Leiki pöpiä – Kalle parantaa”: Kalle kotipsykiatri -tietokone- ohjelma tekoälyn popularisoijana 1980-luvulla Petri Saarikoski1, Markku Reunanen2 & Jaakko Suominen3 Tekoälyä koskevalla vilkkaalla julkisuuskeskustelulla on oma monipuolinen taustahistoriansa. Artikke- lissa käsitellään Pekka Tolosen luoman Kalle kotipsykiatri -ohjelman vaiheita 1980-luvun tietokoneleh- distössä. Kalle kotipsykiatri tunnetaan varhaisena esimerkkinä tekoälyä simuloivasta keskusteluohjel- masta, jonka Commodore 64 -käännösversion koodivirheitä korjailtiin yli vuoden ajan kotitietokoneisiin erikoistuneessa MikroBitti -lehdessä. Johdanto Tekoälyltä koskevalta keskustelulta voi tuskin välttyä nykyään missään. Tekoäly esiintyy uu- tisissa, poliittisissa puheissa, mediajulkisuudessa sekä ihmisten kasvokkais- ja nettikeskuste- luissa. Tekoälyllä viitataan muun muassa robotteihin, erilaisiin digitaalisiin -

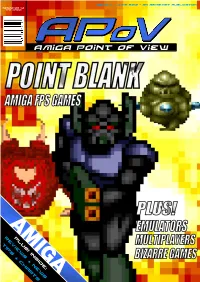

Apov Issue 4 Regulars

issue 4 - june 2010 - an abime.net publication the amiga dedicated to amIga poInt of vIew AMIGA reviews w news tips w charts apov issue 4 regulars 8 editorial 10 news 14 who are we? 116 charts 117 letters 119 the back page reviews 16 leander 18 dragon's breath 22 star trek: 25th anniversary 26 operation wolf 28 cabal 30 cavitas 32 pinball fantasies 36 akira 38 the king of chicago ap o 40 wwf wrestlemania v 4 42 pd games 44 round up 5 features 50 in your face The first person shooter may not be the first genre that comes to mind when you think of the Amiga, but it's seen plenty of them. Read about every last one in gory detail. “A superimposed map is very useful to give an overview of the levels.” 68 emulation station There are literally thousands of games for the Amiga. Not enough for you? Then fire up an emulator and choose from games for loads of other systems. Wise guy. “More control options than you could shake a joypad at and a large number of memory mappers.” 78 sensi and sensibility Best football game for the Amiga? We'd say so. Read our guide to the myriad versions of Sensi. “The Beckhams had long lived in their estate, in the opulence which their eminence afforded them.” wham into the eagles nest 103 If you're going to storm a castle full of Nazis you're going to need a plan. colorado 110 Up a creek without a paddle? Read these tips and it'll be smooth sailing. -

The Gamification of Digital Gaming – Video Game Competitions and High Score Tables As a Prehistory of E-Sports in Finland in the 1980S and Early 1990S

The Gamification of Digital Gaming – Video Game Competitions and High Score Tables as a Prehistory of E-Sports in Finland in the 1980s and Early 1990s Petri Saarikoski, Jaakko Suominen University of Turku Finland [email protected], [email protected] Markku Reunanen Aalto University Finland [email protected] Abstract: The aim of this paper is to examine the “prehistory” of E-sports from the Finnish perspective. In the context of the GamiFIN conference, we approach E-sports as a gamified form of video gaming. In particular, we study the early Finnish game championships of the 1980s and the early 1990s as well as the high score lists of Finnish computer and video game magazines. We ask the question: how did these publications and activities construct video gaming as a socially-experienced competitive practice? In addition, we seek answers to the following questions: Who were the early video game contestants? How was competitive gaming presented in media? What kind of rules were defined for the contests? How was cheating dealt with? Keywords: Competitive gaming, game history, e-sports, high score tables, Pac-Man 1. Introduction Academic research on E-sports has focused on competitive game playing as a contemporary popular cultural phenomenon. The studies have touched upon, for instance, questions on game playing and tactics, comparisons between E-sports and traditional sports consumers’ behavior, as well as other activities revolving around E-sports. (Hamari & Sjöblom 2017.) The studies often briefly mention the history of competitive gaming and typically date its roots back to the activities from the mid or late 1990s that took place in the US, South Korea, UK, and other countries, in relation to different online game genres and the rising interest towards competitive gaming (e.g. -

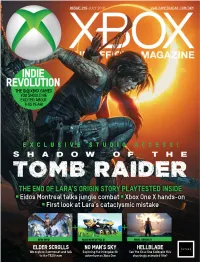

The End of Lara's Origin Story

ISSUE 215 JULY 2018 W W W.GAMESRADAR.COM/OXM THE ID@XBOX GAMES YOU SHOULD BE EXCITED ABOUT THIS YEAR! EXCLUSIVE STUDIO ACCESS! THE END OF LARA’S ORIGIN STORY PLAYTESTED INSIDE Q Eidos Montreal talks jungle combat QXbox One X hands-on QFirst look at Lara’s cataclysmic mistake NEW INFO! HUGE NEW DETAILS! FINAL VERDICT! ELDER SCROLLS NO MAN’S SKY HELLBLADE We explore Summerset and talk Exploring the intergalactic Can the Xbox One X elevate this to the TESO team adventure on Xbox One stunningly animated title? INTRO ISSUE 215 JULY 2018 Mexican EDITORIAL Editor Stephen Ashby Seryph01 [email protected] Group Senior Art Editor Warren Brown wozbrown Deputy Editor Daniella Lucas CelShadedDreams Production Editor Russell Lewin FloatedRelic264 Paul Taylor Taylor Paul Paulus McT Paulus Staff Writer Adam Bryant FirebreedpunkUnder Down Man Our CONTRIBUTORS Writing Kimberley Ballard, Vikki Blake, Zoe Delahunty-Light, Ian Dransfield, Fraser Gilbert, Callum Hart, Steve Hogarty, Leon Hurley, Phil Iwaniuk, cave Martin Kitts, Dave Meikleham, Dom Peppiatt, Dom Reseigh-Lincoln, Paul Walker-Emig, Josh West, Ben Wilson Art Rebecca Shaw All copyrights and trademarks are recognized and respected BUSINESS Vice President, Sales Stacy Gaines, [email protected] We managed to get another huge scoop this Vice President, Strategic Partnerships Isaac Ugay, [email protected] East Coast Account Director month after Eidos Montreal invited us over to Brandie Rushing, [email protected] East Coast Account Director Michael Plump, [email protected] Midwest Account Director Canada to see the latest Tomb Raider title, play Jessica Reinert, [email protected] West Coast Account Director Austin Park, [email protected] the first hour, and chat to the team about what we West Coast Account Director Brandon Wong, [email protected] West Coast Account Manager can expect from the final chapter of Lara’s origins Tad Perez, [email protected] Director of Marketing Robbie Montinola Director, Client Services Tracy Lam story. -

Gerber Gear Full Line Product Catalog

PRODUCT CATALOG + ii 1 Badassador (noun) – doing whatever it takes, even if that’s everything you got; finding out you have more inside than you thought; out there in the woods and swamp and sea, in it; the act of being Unstoppable. BLOG.GERBERGEAR.COM/BADASSADORS/ 2 AMERICAN ORIGINAL BORN ON THE BUILT TO SPIRIT INNOVATOR BATTLEFIELD ENDURE Built through grit, passion Gerber products challenge Gerber understands trust, Made to save time or save and hard work, Gerber's the staus quo, and bring and knows great products the day, Gerber tools are competitive spirit is new solutions to common can be the difference built for use and will stand unwavering. problems. between life and death. the test of time. 3 TOC KNIVES 5 New 6 Fixed Blade 22 Assisted Opening 42 Automatic 53 Folding Clip 56 Folding Sheath 78 Multi-Blade 84 Pocket Folding 85 CUTTING TOOLS 88 New 89 Axes 92 Machetes 97 Pruners + Shears 1Ø2 Saws 1Ø4 MULTI-TOOLS 1Ø9 New 111 One-Hand Opening 112 Butterfly Opening 116 Solid State 123 Specialized 125 Accessories 129 LIGHTING 130 EQUIPMENT 137 New 139 Accessories 144 Breaching 148 Kits 149 Sharpeners 155 Shovels 157 Specialized 159 INDEX 162 GERBERGEAR.COM 4 KNIVES + KNIVES | FIXED BLADE 5 Ø6 AUTO™ 1ØTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION Honoring the American heritage and time-tested durability of the Ø6 Automatic family, Gerber proudly presents an innovative evolution of everything that made the original the best in its class. The Ø6 Automatic 1Øth Anniversary knife is a special edition celebration of Gerber’s craftsmanship, design, and spirit. -

Producción De Una Experiencia De Horror Inmersivo Utilizando Un Entorno De Desarrollo De Videojuegos Y Un Visor De Realidad Virtual

PRODUCCIÓN DE UNA EXPERIENCIA DE HORROR INMERSIVO UTILIZANDO UN ENTORNO DE DESARROLLO DE VIDEOJUEGOS Y UN VISOR DE REALIDAD VIRTUAL Yusef Abubakra Abubakra Miguel Andrés Herrero Javier Fernández Villanueva David Martín Sanz Alejandro Zabala Hidalgo Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de Informática Memoria de Trabajo de Fin de Grado en Ingeniería Informática y Grado en Ingeniería del Software Madrid, 19 de junio de 2015 Director: Federico Peinado Gil Autorización de difusión y utilización Yusef Abubakra Abubakra, Miguel Andrés Herrero, Javier Fernández Villanueva, David Martín Sanz y Alejandro Zabala Hidalgo, responsables de este Trabajo Fin de Grado, autorizamos a la Universidad Complutense de Madrid a difundir y utilizar con fines académicos, no comerciales y mencionando expresamente a sus autores, tanto la propia memoria del trabajo, como el código, los contenidos audiovisuales -incluyendo imágenes de los autores-, la documentación y el prototipo desarrollado. Fdo. D. Yusef Abubakra Abubakra Fdo. D. Miguel Andrés Herrero Fdo. D. Javier Fernández Villanueva Fdo. D. David Martín Sanz Fdo. D. Alejandro Zabala Hidalgo I II Índice Índice de figuras ............................................................................................................ VII Índice de tablas y gráficas .............................................................................................. IX Resumen ......................................................................................................................... XI Abstract ........................................................................................................................