Columbia River Basin Toxics Reduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbia River Crossing I-5 Immersed Tunnel I-5 Immersed Tunnel Advantages Immersed Tunnel

6 Sections 500 feet long x 170 feet wide 3,000 ft. Columbia River Crossing I-5 Immersed Tunnel I-5 Immersed Tunnel Advantages Immersed Tunnel Navigation clearances Aviation clearances No freeway noise on river front No mile-long elevated bridge ramps dividing Vancouver Aberdeen Casting Basin 165 x 910 feet Baltimore's Fort McHenry Tunnel Completed 1985 1.4 miles 8 lanes – 4 tubes 115,000 vehicles/day I-95 Immersed Tunnel saved Baltimore’s Inner Harbor 1985 1959 freeway plan Vancouver’s Massey Tunnel under Fraser River October 14, 2019 Vancouver’s Fraser River Bridge replaced by Tunnel 10 lanes April 1, 2020 Vancouver’s Columbia River Bridge replaced by Tunnel Øresund Bridge 20 sections x 577ft = 2.2miles & Tunnel 1999 138ft wide Øresund Tunnel Section 20 sections x 577ft =2.2miles 138ft wide Columbia River Tunnel Section 6 sections x 500ft = 0.6miles 170ft wide Immersed Tunnels About six 500 foot immersed tunnel sections could be a simple, elegant, and cost effective solution to the I-5 Columbia River Crossing. The Aberdeen Casting Basin used to build the SR 520 bridge pontoons would be well suited to casting tunnel sections. https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2014/11/12/SR520-Factsheet-Pontoons- February2017.pdf In 1985 Baltimore completed the Fort McHenry Immersed Tunnel and saved its famous Inner Harbor from encirclement by I-95 concrete bridge. https://www.baltimorebrew.com/2011/04/29/the-senator-and-the-highway/ Vancouver, Canada rejected a ten lane bridge over the Fraser in favor of an immersed tunnel. https://www.enr.com/blogs/15-evergreen/post/47724-vancouvers-george-massey- tunnel-replacement-may-now-be-a-tunnel-instead-of-a-bridge The 1999 Oresund Bridge & Immersed Tunnel connects Sweden to Denmark. -

The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement

Volume 26 Issue 2 U.S. - Canada Transboundary Resource Issues Spring 1986 The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement Jackie Krolopp Kirn Marion E. Marts Recommended Citation Jackie K. Kirn & Marion E. Marts, The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement, 26 Nat. Resources J. 261 (1986). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol26/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. JACKIE KROLOPP KIRN* and MARION E. MARTS** The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement SETTING AND BACKGROUND The Skagit River is a short but powerful stream which rises in the mountains of southwestern British Columbia, cuts through the northern Cascades in a spectacular and once-remote mountain gorge, and empties into Puget Sound approximately sixty miles north of Seattle. The beautiful mountain scenery of the heavily glaciated north Cascades was formally recognized in the United States by the creation of the North Cascades National Park and the Ross Lake National Recreation Area in 1968, and earlier in British Columbia by creation of the E.C. Manning Provincial Park. The Ross Lake Recreation Area covers the narrow valley of the upper Skagit River in Washington and portions of several tributary valleys. It was created as a political and, to environmentalists who wanted national park status for the entire area, controversial, compromise which accom- modated the city of Seattle's Skagit River Project and the then-planned North Cascades Highway. -

Overview of Wheat Movement on the Columbia River Report Prepared August 17, 2016 All Data Based on Five Year Averages (2011-2015)

Overview of Wheat Movement on the Columbia River Report Prepared August 17, 2016 All data based on five year averages (2011-2015) The Columbia-Snake River grain handling system includes: o 7 grain export terminals. o 26 up-country grain barge loading terminals along 360 miles of navigable river. o Eight dams that lift a barges a combined 735 feet. o 80 barges controlled by two companies (Shaver and Tidewater). The seven export terminals on the Columbia River annually export 26.5 MMT of grain, including 11.7 MMT of wheat. This makes the Columbia River the third largest grain export corridor in the world behind the Mississippi River and the Parana River in South America. Grain exports from the Columbia River continue to grow each year. Every year approximately 4.0 MMT of wheat, largely Soft White, is shipped down the Columbia River via barge from the states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. This is equivalent to: o 34% of all wheat exports from the Columbia River. o 15% of all grain exports from the Columbia River. o 15% of all wheat exported from the United States. o 70% of all wheat exported from the Pacific Northwest. o 50% of all wheat produced in the Pacific Northwest. The wheat moved by barge is largely sourced from the upper river system. o 18% from between Bonneville Dam and McNary Dam. o 36% from between McNary Dam and Lower Monumental Dam. o 46% from between Lower Monumental Dam and Lewiston, Idaho. o 54% of the wheat moved by barge moves through one or more of the four Lower Snake River dams. -

The Columbia River Gorge: Its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway by IRA A

VOLUMB 2 NUMBBI3 NOVBMBBR, 1916 . THE .MINERAL · RESOURCES OF OREGON ' PuLhaLed Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Mitchell Point tunnel and viaduct, Columbia River Hi~hway The .. Asenstrasse'' of America The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations Entered aa oeoond cl,... matter at Corvallis, Ore., on Feb. 10, l9lt, accordintt to tbe Act or Auc. :U, 1912. .,.,._ ;t ' OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY COMMISSION On1cm or THm Co><M188ION AND ExmBIT OREGON BUILDING, PORTLAND, OREGON Orncm or TBm DtBIICTOR CORVALLIS, OREGON .,~ 1 AMDJ WITHY COMBE, Governor HENDY M. PABKB, Director C OMMISSION ABTBUB M. SWARTLEY, Mining Engineer H. N. LAWRill:, Port.land IRA A. WILLIAMS, Geologist W. C. FELLOWS, Sumpter 1. F . REDDY, Grants Pass 1. L. WooD. Albany R. M. BIITT8, Cornucopia P. L. CAI<PBELL, Eugene W 1. KEBR. Corvallis ........ Volume 2 Number 3 ~f. November Issue {...j .· -~ of the MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Published by The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology ~•, ;: · CONTAINING The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History l Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway t. By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations 1916 ILLUSTRATIONS Mitchell Point t unnel and v iaduct Beacon Rock from Columbia River (photo by Gifford & Prentiss) front cover Highway .. 72 Geologic map of Columbia river gorge. 3 Beacon Rock, near view . ....... 73 East P ortland and Mt. Hood . 1 3 Mt. Hamilton and Table mountain .. 75 Inclined volcanic ejecta, Mt. Tabor. 19 Eagle creek tuff-conglomerate west of Lava cliff along Sandy river. -

2020 EARLY SEASON REPORT Columbia Shuswap Regional District Golden, BC (Area ‘A’) Mosquito Program

2020 EARLY SEASON REPORT Columbia Shuswap Regional District Golden, BC (Area ‘A’) Mosquito Program Submitted by Morrow BioScience Ltd. April 17, 2020 www.morrowbioscience.com Toll Free: 1-877-986-3363 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 2 Monitoring Methodology _______________________________________________________ 2 Data Management ____________________________________________________________ 4 Education Outreach ____________________________________________________________ 4 Season Forecast _______________________________________________________________ 5 Snowpack ________________________________________________________________________ 5 Weather __________________________________________________________________________ 7 Reporting Schedule ____________________________________________________________ 8 Contacts _____________________________________________________________________ 8 References ___________________________________________________________________ 9 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Snow basin indices for the Upper Columbia Basin determined by the 1 April 2018, 1 April 2019, and 1 April 2020 bulletins ............................................................................................ 7 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix I. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) regarding Aquabac®, the bacterial larvicide utilized by MBL (a.i., Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis) Appendix -

The Damnation of a Dam : the High Ross Dam Controversy

THE DAMYIATION OF A DAM: TIIE HIGH ROSS DAM CONTROVERSY TERRY ALLAN SIblMONS A. B., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1968 A THESIS SUBIUTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY May 1974 All rights reserved. This thesis may not b? reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Terry Allan Simmons Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Damnation of a Dam: The High Ross Dam Controversy Examining Committee: Chairman: F. F. Cunningham 4 E.. Gibson Seni Supervisor / /( L. J. Evendon / I. K. Fox ernal Examiner Professor School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University rhe righc to lcnd my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed ' without my written permission. Title of' ~hesis /mqqmkm: The Damnation nf a nam. ~m -Author: / " (signature ) Terrv A. S.imrnonze (name ) July 22, 1974 (date) ABSTRACT In 1967, after nearly fifty years of preparation, inter- national negotiations concerning the construction of the High Ross Dan1 on the Skagit River were concluded between the Province of British Columbia and the City of Seattle. -

Columbia River Treaty Review the Idaho Position This Position

Columbia River Treaty Review The Idaho Position This position Statement outlines the current position of a broad range of Idaho stakeholders (identified below and collectively referred to as “Idaho Stakeholders”) on the efforts to modernize the Columbia River Treaty (“CRT”) with Canada. I. Hydropower: The CRT provides for an “entitlement” for power benefits derived from the agreement. See CRT Article V.1 (“Canada is entitled to one half the downstream power benefits determined under Article VII”). The entitlement is determined as “the difference in the hydroelectric power capable of being generated in the United States of America with and without the use of Canadian storage, determined in advance, and is referred to in the Treaty as the downstream power benefits.” CRT Article VII; see also CRT Annex B ¶ 1 (“The downstream power benefits in the United States of America attributable to operation in accordance with Annex A of the storage provided by Canada under Article II will be determined in advance and will be the estimated increase in dependable hydroelectric capacity in kilowatts for agreed critical stream flow periods and the increase in average annual usable hydroelectric energy output in kilowatt hours on the basis of an agreed period of stream flow record”). Over time, this “Canadian Entitlement” has proven to greatly exceed the actual benefits. Discontinuation of the Canadian Entitlement would result “in an overall increase in annual revenue for the United States (about $180 million to $280 million).”1 As explained in the Regional Recommendation, at page 4, “rebalancing is necessary because the present Treaty power benefits are not equitably shared and Canada is deriving substantially greater value from coordinated power operations than the United States.” Idaho Stakeholders take the following position on Hydropower: 1. -

Columbia Snake River System Columbia River Ports

US Army Corps of Engineers Portland District ColumbiaColumbia SnakeSnake RiverRiver SystemSystem FederalFederal InvestmentInvestment ColumbiaColumbia RiverRiver PortsPorts AA CaseCase StudyStudy ColumbiaColumbia SnakeSnake RiverRiver SystemSystem US Army Corps of Engineers FederalFederal InfrastructureInfrastructure Portland District Columbia & Lower Willamette MCR Jetties & Deep Draft Shipping Channel Entrance Channel Vancouver to The Dalles Barge Channel FederalFederal InfrastructureInfrastructure US Army Corps of Engineers Mouth of the Columbia River Portland District North Jetty – 2.5 mi long (4.02 km) South Jetty – 6.6 mi long (10.62 km) Spur Jetty – 0.3 mi long (0.48 km) Entrance Channel – 2600 ft x 55 ft deep (792 m x 16.8 m) Annual Maintenance Dredging: 4.5 Mcy (3.5 hm3) FederalFederal InfrastructureInfrastructure US Army Corps of Engineers PortlandColumbia District & Lower Willamette River Channel 40 foot (12.2 m) x 600 feet (183 m) wide Mouth to Portland & Vancouver - 106 mi (107 km) Willamette River - 10 mi (16 km) Annual Maintenance Dredging -6 Mcy (4.6 hm3) Presently deepening to 43 feet (13.1 km) FederalFederal InfrastructureInfrastructure US Army Corps of Engineers Portland District Columbia & Snake RiverRiver BargeBarge ChannelChannel 359 miles (578 km) from Vancouver, WA to Lewiston, ID 8 locks -14 foot (4.6 m) sill depth; 86 ft x 650 ft (26.2 m x 198.1 m Annual Dredging 200 kcy (15.3 dam3) FederalFederal InfrastructureInfrastructure US Army Corps of Engineers Portland District 8 Locks through Multipurpose Dams 700 ft Vertical Lift (214 m) ColumbiaColumbia SnakeSnake RiverRiver DamsDams US Army Corps of Engineers 88 MultipurposeMultipurpose ProjectsProjects Portland District Power –Generation Cap. 10.3 MWatt Navigation – 359 mi of barge channel Flood Control - 534,000 AF Irrigation –6.5 MAc land (26,304 km2) Recreation – Over 100 Camps, Parks & Recreational Facilities Environmental – Fish Passage Facilities US Army Corps SelectedSelected CommoditiesCommodities of Engineers Portland District ForecastForecast vs.vs. -

Thompson River Watershed Restoration Plan

Thompson River Watershed Restoration Plan March 8, 2018 Upper Thompson River near Bend. Photo Credit: Brian Sugden Page 1 of 99 Acknowledgements Lower Clark Fork Watershed Group (LCFWG) has taken the lead in organizing and drafting the Thompson River Watershed Restoration Plan, but the completion of this plan was only possible with the contribution of many local stakeholders throughout the Thompson River Watershed. A special thank you to all of the community members within the Thompson River Watershed who took the time to complete our online survey and provide us with local input. Authors: Sarah Bowman – Lower Clark Fork Watershed Group Brita Olson – Lower Clark Fork Watershed Group Secondary Authors: Ryan Kreiner – Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks Samantha Tappenbeck – Soil and Water Conservation Districts of Montana Brian Sugden – Weyerhaeuser Company Contributing Stakeholders: Clark Fork Coalition: John DeArment Eastern Sanders County Conservation District: Steve Dagger Flathead Conservation District: Valerie Kurth Green Mountain Conservation District: Leona Gollen Lincoln Conservation District: Becky Lihme Lower Clark Fork Watershed Group: Brita Olson, Jay Stuckey, Jean Dunn, Ruth Watkins, Sarah Bowman, Sean Moran Montana Department of Environmental Quality: Eric Trum Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation: Dave Mousel, Dave Olsen, Mike Anderson, Tony Nelson Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks: Ryan Kreiner Natural Resources Conservation Service (Kalispell Field Office): Angel Rosario Natural Resources Conservation Service -

The Amazing Journey of Columbia River Salmon the Columbia River Basin

BONNEVILLE POWER ADMINISTRATION THE AMAZING JOURNEY OF Columbia River Salmon THE Columbia River Basin The Columbia River starts in Canada and flows through Washington. Then it flows along the Oregon and Washington border and into the Pacific Ocean. Other major rivers empty into the Columbia River. Smaller rivers and streams flow down from the mountains and into those rivers. This entire network of streams and rivers is called the Columbia River Basin. Salmon are born in many of these streams and rivers. They meet up with salmon from other places in the basin as they enter the Columbia River on their amazing journey to the ocean. This map shows the journey of the spring chinook that come from the Snake River in Idaho. Other spring chinook come from streams in Washington and Oregon. mbia lu o C MT N WA ake Sn Columb ia S n a k e OR ID Snak e CA NV LIFE CYCLE OF THE Columbia River Salmon RENEWING THE CYCLE 10 WAITING 1 TO HatCH RETURNING TO SPawNING 9 GROUNDS LEARNING 2 TO SURVIVE CLIMBING FISH 8 LADDERS LEAVING 3 HOME SWIMMING UPSTREAM 7 RIDING TO 4 THE SEA LIVING IN THE OCEAN 6 ENTERING 5 THE ESTUARY 1 ALEVIN REDD YOLK SAC FOUR MONTHS 1 Waiting to hatch Five thousand tiny red eggs lie hidden in a nest of stones Spring approaches, and the salmon slip out of their high in Northwest mountains. The cold, clear water of eggs. Barely an inch long, each of these just-born a shallow stream gently washes over the nest, called a fish, called ALEVIN, has large eyes and a bright orange REDD. -

Columbia River Treaty: Issues for the 21St Century

SCIENCE in the service of WASHINGTON STATE Columbia River Treaty: Issues for the 21st Century Summary of the Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Symposium Held as Part of the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Washington State Academy of Sciences September 15, 2016, Museum of Flight, Seattle, WA February 2017 © 2017 Washington State Academy of Sciences Summary of the Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Symposium Columbia River Treaty: Issues for the 21st Century Columbia River Treaty: Issues for the 21st Century Summary of the Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Symposium held as part of the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Washington State Academy of Sciences September 15, 2016 Museum of Flight, Seattle, WA Proceedings Released February 2017 i Washington State Academy of Sciences Summary of the Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Symposium Columbia River Treaty: Issues for the 21st Century About the Washington State Academy of Sciences The Washington State Academy of Sciences (WSAS) is an organization of Washington state’s leading scientists and engineers dedicated to serving the state with scientific counsel. Formed as a working academy, not an honorary society, the academy is modeled on the National Research Council. Its mission is two-fold: to provide expert scientific and engineering analysis to inform public policymaking in Washington state; and to increase the role and visibility of science in the state. Governor Christine Gregoire authorized legislation establishing WSAS in 2005. Its 12-member Founding Board of Directors was recommended by the presidents of Washington State University and the University of Washington, and was duly appointed by the governor. In April 2007, WSAS was constituted by the Secretary of State as a private, independent 501(c)(3). -

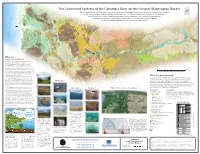

The Connected Systems of the Columbia River on the Oregon

The Connected Systems of the Columbia River on the Oregon-Washington Border WASHINGTON The Columbia River, in its 309-mile course along the Oregon-Washington border, provides a rich and varied environment OREGON for the people, wildlife, and plants living and interacting there. The area’s geology is the basis for the landscape and ecosystems we know today. By deepening our understanding of interactions of Earth systems — geosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere — Earth science helps us manage our greatest challenges and make the most of vital opportunities. ⑮ ⑥ ④ ⑬ ⑧ ⑪ ① ⑦ ② ③ What is a ⑭ ⑫ ⑤ connected system? ⑩ A connected system is a set of interacting components that directly or indirectly influence one another. The Earth system has four major components. The geosphere includes the crust and the interior of the planet. It contains all of the rocky parts of the planet, the processes that cause them to form, and the processes that have caused ⑨ them to change during Earth’s history. The parts can be as small 0 10 20 40 Miles ∆ N as a mineral grain or as large as the ocean floor. Some processes act slowly, like the gradual wearing away of cliffs by a river. Geosphere Others are more dramatic, like the violent release of gases and magma during a volcanic eruption. ① What is a geologic map? The fluid spheres are the liquid and gas parts of the Earth system. The atmosphere includes the mixture of gases that Geologic maps show what kinds of rocks and structures make up a landscape. surrounds the Earth. The hydrosphere includes the planet’s The geologic makeup of an area can strongly influence the kinds of soils, water water system.