The Skagit-High Ross Controversy: Negotiation and Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flooding the Border: Development, Politics, and Environmental Controversy in the Canadian-U.S

FLOODING THE BORDER: DEVELOPMENT, POLITICS, AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROVERSY IN THE CANADIAN-U.S. SKAGIT VALLEY by Philip Van Huizen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) June 2013 © Philip Van Huizen, 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a case study of the 1926 to 1984 High Ross Dam Controversy, one of the longest cross-border disputes between Canada and the United States. The controversy can be divided into two parts. The first, which lasted until the early 1960s, revolved around Seattle’s attempts to build the High Ross Dam and flood nearly twenty kilometres into British Columbia’s Skagit River Valley. British Columbia favoured Seattle’s plan but competing priorities repeatedly delayed the province’s agreement. The city was forced to build a lower, 540-foot version of the Ross Dam instead, to the immense frustration of Seattle officials. British Columbia eventually agreed to let Seattle raise the Ross Dam by 122.5 feet in 1967. Following the agreement, however, activists from Vancouver and Seattle, joined later by the Upper Skagit, Sauk-Suiattle, and Swinomish Tribal Communities in Washington, organized a massive environmental protest against the plan, causing a second phase of controversy that lasted into the 1980s. Canadian and U.S. diplomats and politicians finally resolved the dispute with the 1984 Skagit River Treaty. British Columbia agreed to sell Seattle power produced in other areas of the province, which, ironically, required raising a different dam on the Pend d’Oreille River in exchange for not raising the Ross Dam. -

License Application Boundary Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 2144)

License Application Boundary Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 2144) Seattle City Light September 2009 LICENSE APPLICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS AND DEFINITIONS List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. ix List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... xiv List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................................... xxi INITIAL STATEMENT EXHIBIT A: PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 Contents and Purpose of This Exhibit .............................................................................. A-1 2 General Project Description............................................................................................... A-1 3 Project Area and Vicinity ................................................................................................... A-1 4 Project Lands ...................................................................................................................... A-5 5 License Requirements ......................................................................................................... A-5 5.1. License Articles ............................................................................................................. A-5 5.2. Additional FERC Orders ............................................................................................... A-8 5.3. Other Licenses/Permits -

Wapiti River Water Management Plan Summary

Wapiti River Water Management Plan Summary Wapiti River Water Management Plan Steering Committee February 2020 Summary The Wapiti River basin lies within the larger Smoky/Wapiti basin of the Peace River watershed. Of all basins in the Peace River watershed, the Wapiti basin has the highest concentration and diversity of human water withdrawals and municipal and industrial wastewater discharges. The Wapiti River Water Management Plan (the Plan) was developed to address concerns about water diversions from the Wapiti River, particularly during winter low-flow periods and the potential negative impacts to the aquatic environment. In response, a steering committee of local stakeholders including municipalities, Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation, industry, agriculture, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Mighty Peace Watershed Alliance (MPWA), supported by technical experts from Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP), was established. The steering committee initiated the development of a water management plan that includes a Water Conservation Objective (WCO) and management recommendations for the Wapiti River basin from the British Columbia border to its confluence with the Smoky River. A WCO is a limit to the volume of water that can be withdrawn from the Wapiti River, ensuring that water flow remains in the river system to meet ecological objectives. The Plan provides guidance and recommendations on balancing the needs of municipal water supply, industry uses, agriculture and other uses, while maintaining a healthy aquatic ecosystem in the Alberta portion of the Wapiti River basin. Wapiti River Water Management Plan | Summary 2 Purpose and Objectives of the Plan The Plan will be provided as a recommendation to AEP and if adopted, would form policy when making water allocation decisions under the Water Act, and where appropriate, under the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act by establishing a WCO for the Wapiti River. -

Columbia River Crossing I-5 Immersed Tunnel I-5 Immersed Tunnel Advantages Immersed Tunnel

6 Sections 500 feet long x 170 feet wide 3,000 ft. Columbia River Crossing I-5 Immersed Tunnel I-5 Immersed Tunnel Advantages Immersed Tunnel Navigation clearances Aviation clearances No freeway noise on river front No mile-long elevated bridge ramps dividing Vancouver Aberdeen Casting Basin 165 x 910 feet Baltimore's Fort McHenry Tunnel Completed 1985 1.4 miles 8 lanes – 4 tubes 115,000 vehicles/day I-95 Immersed Tunnel saved Baltimore’s Inner Harbor 1985 1959 freeway plan Vancouver’s Massey Tunnel under Fraser River October 14, 2019 Vancouver’s Fraser River Bridge replaced by Tunnel 10 lanes April 1, 2020 Vancouver’s Columbia River Bridge replaced by Tunnel Øresund Bridge 20 sections x 577ft = 2.2miles & Tunnel 1999 138ft wide Øresund Tunnel Section 20 sections x 577ft =2.2miles 138ft wide Columbia River Tunnel Section 6 sections x 500ft = 0.6miles 170ft wide Immersed Tunnels About six 500 foot immersed tunnel sections could be a simple, elegant, and cost effective solution to the I-5 Columbia River Crossing. The Aberdeen Casting Basin used to build the SR 520 bridge pontoons would be well suited to casting tunnel sections. https://www.wsdot.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2014/11/12/SR520-Factsheet-Pontoons- February2017.pdf In 1985 Baltimore completed the Fort McHenry Immersed Tunnel and saved its famous Inner Harbor from encirclement by I-95 concrete bridge. https://www.baltimorebrew.com/2011/04/29/the-senator-and-the-highway/ Vancouver, Canada rejected a ten lane bridge over the Fraser in favor of an immersed tunnel. https://www.enr.com/blogs/15-evergreen/post/47724-vancouvers-george-massey- tunnel-replacement-may-now-be-a-tunnel-instead-of-a-bridge The 1999 Oresund Bridge & Immersed Tunnel connects Sweden to Denmark. -

108Th Congress of the United States WASHINGTON CANADA

108th Congress of the United States WASHINGTON CANADA 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 33 3 3 3 333333 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Osoyoos Nooksack 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Lake Trust Land 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 r 3 e 3 3 v 3 3 i 3 R 3 Birch 3 ck 3 Ross Strait of Georgia 3 sa 3 3 Bay ok 3 o 3 N 3 3 Nooksack 3 Lake 3 3 3 3 Trust Land 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 North Cascades 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 National Park 3 WHATCOM 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 PEND 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Lummi Nooksack Res 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Res 3 3 3 OREILLE 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Bellingham 3 3 3 Bay 3 33 3 3 Pend Oreille River 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Bellingham 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Ross Lake 3 3 Cowlitz 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 NRA 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Bay 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Okanogan River 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Samish 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 TDSA 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Samish 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Rosario Strait Bay 3 3 FERRY 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Upper Skagit Res 3 SAN JUAN 3 Haro Strait 3 North Cascades 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 National Park 3 OKANOGAN Upper Skagit Res 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Skagit River 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Padilla 3 3 3 3 Griffin Bay 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Bay 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 US Coast Guard Station 3 3 3 SKAGIT 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Neah Bay 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 STEVENS 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 -

Overview of Wheat Movement on the Columbia River Report Prepared August 17, 2016 All Data Based on Five Year Averages (2011-2015)

Overview of Wheat Movement on the Columbia River Report Prepared August 17, 2016 All data based on five year averages (2011-2015) The Columbia-Snake River grain handling system includes: o 7 grain export terminals. o 26 up-country grain barge loading terminals along 360 miles of navigable river. o Eight dams that lift a barges a combined 735 feet. o 80 barges controlled by two companies (Shaver and Tidewater). The seven export terminals on the Columbia River annually export 26.5 MMT of grain, including 11.7 MMT of wheat. This makes the Columbia River the third largest grain export corridor in the world behind the Mississippi River and the Parana River in South America. Grain exports from the Columbia River continue to grow each year. Every year approximately 4.0 MMT of wheat, largely Soft White, is shipped down the Columbia River via barge from the states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. This is equivalent to: o 34% of all wheat exports from the Columbia River. o 15% of all grain exports from the Columbia River. o 15% of all wheat exported from the United States. o 70% of all wheat exported from the Pacific Northwest. o 50% of all wheat produced in the Pacific Northwest. The wheat moved by barge is largely sourced from the upper river system. o 18% from between Bonneville Dam and McNary Dam. o 36% from between McNary Dam and Lower Monumental Dam. o 46% from between Lower Monumental Dam and Lewiston, Idaho. o 54% of the wheat moved by barge moves through one or more of the four Lower Snake River dams. -

The Columbia River Gorge: Its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway by IRA A

VOLUMB 2 NUMBBI3 NOVBMBBR, 1916 . THE .MINERAL · RESOURCES OF OREGON ' PuLhaLed Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Mitchell Point tunnel and viaduct, Columbia River Hi~hway The .. Asenstrasse'' of America The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations Entered aa oeoond cl,... matter at Corvallis, Ore., on Feb. 10, l9lt, accordintt to tbe Act or Auc. :U, 1912. .,.,._ ;t ' OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY COMMISSION On1cm or THm Co><M188ION AND ExmBIT OREGON BUILDING, PORTLAND, OREGON Orncm or TBm DtBIICTOR CORVALLIS, OREGON .,~ 1 AMDJ WITHY COMBE, Governor HENDY M. PABKB, Director C OMMISSION ABTBUB M. SWARTLEY, Mining Engineer H. N. LAWRill:, Port.land IRA A. WILLIAMS, Geologist W. C. FELLOWS, Sumpter 1. F . REDDY, Grants Pass 1. L. WooD. Albany R. M. BIITT8, Cornucopia P. L. CAI<PBELL, Eugene W 1. KEBR. Corvallis ........ Volume 2 Number 3 ~f. November Issue {...j .· -~ of the MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Published by The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology ~•, ;: · CONTAINING The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History l Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway t. By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations 1916 ILLUSTRATIONS Mitchell Point t unnel and v iaduct Beacon Rock from Columbia River (photo by Gifford & Prentiss) front cover Highway .. 72 Geologic map of Columbia river gorge. 3 Beacon Rock, near view . ....... 73 East P ortland and Mt. Hood . 1 3 Mt. Hamilton and Table mountain .. 75 Inclined volcanic ejecta, Mt. Tabor. 19 Eagle creek tuff-conglomerate west of Lava cliff along Sandy river. -

National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-O018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service skagit ^VQT & Newhalem Creek National Register of Historic Places Hydroeiectirc Projects Continuation Sheet Section number ___ Page ___ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 96000416 Date Listed: 4/26/96 Skagit River & Newhalem Creek Hvdroelectirc Projects Whatcom WA Property Name County State Hydroelectric Power Plant MPS Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature of tty^Keejifer Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Photographs: The SHPO has verified that the 1989 photographs accurately document the current condition and integrity of the nominated resources. Historic Photos #1-26 are provided as photocopy duplications. Resource Count: The resource count is revised to read: Contributing Noncontributing 21 6 buildings 2 - sites 5 6 structures 1 - objects 29 12 total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register 16 . A revised inventory list is appended to clarify the resource count and contributing status of properties in the district, particularly at the powerplant/dam sites. (See attached) This information was confirmed with Lauren McCroskey of the WA SHPO. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Skagit River & Newhalem Creek National Register of Historic Places Hydroelectirc Projects Continuation Sheet Section number The following is a list of the contributing and noncontributing resources within the district, beginning at its westernmost—downstream—end, organized according to geographic location. -

2020 EARLY SEASON REPORT Columbia Shuswap Regional District Golden, BC (Area ‘A’) Mosquito Program

2020 EARLY SEASON REPORT Columbia Shuswap Regional District Golden, BC (Area ‘A’) Mosquito Program Submitted by Morrow BioScience Ltd. April 17, 2020 www.morrowbioscience.com Toll Free: 1-877-986-3363 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________ 1 Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 2 Monitoring Methodology _______________________________________________________ 2 Data Management ____________________________________________________________ 4 Education Outreach ____________________________________________________________ 4 Season Forecast _______________________________________________________________ 5 Snowpack ________________________________________________________________________ 5 Weather __________________________________________________________________________ 7 Reporting Schedule ____________________________________________________________ 8 Contacts _____________________________________________________________________ 8 References ___________________________________________________________________ 9 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Snow basin indices for the Upper Columbia Basin determined by the 1 April 2018, 1 April 2019, and 1 April 2020 bulletins ............................................................................................ 7 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix I. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) regarding Aquabac®, the bacterial larvicide utilized by MBL (a.i., Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis) Appendix -

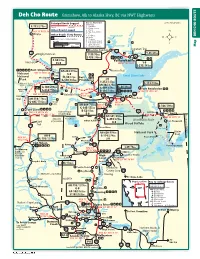

Deh Cho Route Grimshaw, AB, to Alaska Hwy, BC Via NWT Highways

Deh Cho Route Grimshaw, AB, to Alaska Hwy, BC via NWT Highways Key to Advertiser © The MILEPOST® Principal Route Logged Services -Camping C-173/278km Paved Unpaved C D -Dump Station Other Roads Logged d -Diesel N63˚16’ W123˚36’ G -Gas (reg., unld.) r -Ice e Wrigley I v Other Roads Ferry Routes i L -Lodging R Slemmon Lake M -Meals e f DEH CHO ROUTE Refer to Log for Visitor Facilities P -Propane i -Car Repair (major) n Scale R t k r -Car Repair (minor) w t o 0 20 Miles l S -Store (grocery) Marion l Map 0 20 Kilometres -Telephone (pay) Russell Lake e T Lake Y PRae-Edzo/Behchoko Ingraham Trail 3 Prosperous 1 w Lake Prelude L. Y-43/69km Wrigley Extension Y-59/95km 4 Tibbett L. M J-153/246km SbP Reid L. wt ac C-38/61km Yellowknife Free Ferry ke Y-0 nz FS-0 N62˚27’ W114˚21’ ie J-212/341km SwtbP Fort Simpson Frontier Trail AH-244/393km Mills 3 Nahanni N61˚51’ W121˚20’ w Free C-0 Lake Ferry wt Great Slave Lake National Checkpoint FS-38/61km Fort bP J-0 Park er G-550/885km Providence Riv 1 Y-212/341km Nahanni Butte R E-114/183km 4,579 ft./1,396m iver AH-385/620km Sw A-180/290km w G-409/659km E-24/38km Nahanni▲ Fort Resolution bP G-614/988km r Butte ive w B-116/186km wtbP N61˚10’ W113˚41’ R ut t N61˚04’ Kakisa N61˚05’ W122˚51’ Tro Waterfalls Route w Hay 6 W117˚30’ Lake S Liard t 1 River w l Trout w a sa Pine Point aki R v Trail AH-110/176km Lake t K iv 2 5 er e G-685/1102km Trout Tathina Lake Enterprise N60˚48’ Lake t AH-449/723km N60˚33’ P W115˚47’ w R E-186/300km Dogface W116˚08’ iv G-345/555km e wtbP Lake r d Fort Liard SwbP r NORTHWEST B-52/83km -

The Damnation of a Dam : the High Ross Dam Controversy

THE DAMYIATION OF A DAM: TIIE HIGH ROSS DAM CONTROVERSY TERRY ALLAN SIblMONS A. B., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1968 A THESIS SUBIUTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Geography SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY May 1974 All rights reserved. This thesis may not b? reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Terry Allan Simmons Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: The Damnation of a Dam: The High Ross Dam Controversy Examining Committee: Chairman: F. F. Cunningham 4 E.. Gibson Seni Supervisor / /( L. J. Evendon / I. K. Fox ernal Examiner Professor School of Community and Regional Planning University of British Columbia PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University rhe righc to lcnd my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed ' without my written permission. Title of' ~hesis /mqqmkm: The Damnation nf a nam. ~m -Author: / " (signature ) Terrv A. S.imrnonze (name ) July 22, 1974 (date) ABSTRACT In 1967, after nearly fifty years of preparation, inter- national negotiations concerning the construction of the High Ross Dan1 on the Skagit River were concluded between the Province of British Columbia and the City of Seattle. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES December 1969-January 1970 2 THE WILD CASCADES JXTOR/rH CASCADE3S TJTSTDIEiR. AT1 T_As.C> Je^ BATTLE LINES DRAWN by The Kerosene Kid duty it should have been to protect the park. Each such campaign has been accompanied by barrages of propaganda that the resources of the park were essential to the continued growth of the surrounding area or that new roads were needed along the wilderness beach or across the park's wilderness core "to open it up for the peepul. " Each time the friends of Olympic have rallied, mounted counter-attacks and saved the park. We have no reason to believe the history of the North Cascades over the next third of a century will be any different. But, to para phrase Mr. Churchill, the North Cascades Conservation Council (N3C) was not organized to preside over the dissolution of the North Cascades. We expect attacks and we confi dently expect to win. To prevent Seattle City Light from imple menting its destructive proposals in the Ross Lake National Recreation Area will require as If any conservationist felt he was honor tough a fight as conservationists ever have ably discharged from the wars upon passage waged. The nature of the adversary contrib of the 1968 North Cascades Act, he lacked utes to the difficulty of the battle. Seattle City knowledge of the history of the American Light is no ordinary despoiler of wilderness. National Park system. He may have said to In fact, it's hard to say just what Seattle City himself, "Whew! I'm glad that's over.