Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1966 HON

E1966 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 19, 2012 founded by their ancestors 142 years ago has hired by David G. Volkert as a project engi- Sixth District of North Carolina, just won its contributed to our society. neer in 1960. third straight state high school football cham- The most notable member of the family was Over the last five decades, Mr. King has wit- pionship. This time, however, the title capped Colonel John Stevens III. During the Revolu- nessed many changes in the Mobile- a perfect 15–0 season. tionary War, he was appointed to be a captain headquartered engineering company which On December 1, 2012, the Nighthawks of in Washington’s Army at age twenty-seven. has grown to become one of the top-ranked Northern Guilford High School defeated Char- Later he was promoted to Colonel, and col- engineering, planning, and environmental con- lotte Catholic 64–26 to capture its third con- lected taxes for the American cause as Treas- sulting firms in the United States. secutive NCHSAA Class 3–AA championship. urer of New Jersey. After the war in 1784, he Keith served as president from 1983 until Senior T.J. Logan led the way by rushing for purchased land that is now Hoboken, and in- 2007 and CEO until 2011. Volkert, Inc. has an unbelievable 510 yards and scoring eight cludes the current campus for Stevens Insti- grown continuously and opened operations touchdowns. This was the third straight title for tute of Technology. centers in 11 States employing over 600 asso- longtime Head Coach Johnny Roscoe. -

PUBLIC WORKS BOARD DEFERS PAYMENT on Contraa

CITIZI SOUTH AMROY, N J Uu Tho* ?i% Thursday, February 25, iWO Price 5c (7c owl of town) PUBLIC WORKS BOARD DEFERS PAYMENT ON CONTRAa Members of the Board of Bergen Hill Gettin, Public Works, asserting dis- l-lncb Circuit Line satisfaction over work per- Michael*Nagle. Superin- formed under contract by tendent of Public Works. an engineering firm, have informed the.board that a decided against paying the new 8-lnch water Hne in fuki sum as submitted In a the Bergen Hijl sestion of till to them. * town will be completely in- . A balance of S1T.759.01 re- stalled in about two w?eks mains on account out of a if the weather permits Tli» t:>i;H bill rorwarded by work is being performed by U-Pine on work done contractor Adam Sadowski. in the local water tteat- The oid ttne.-whieh ft-be- nt plant Members of the ing replaced, consisted of )r>;nt\ pointed out that the alternate 4-inch and e^ln^h nal contract catted for Piping. A number of cracks expenditure of $27,949 had been discovered In th« which $27,585,59 had old pipes. paid to date. The $1,- The superintendent show- ii f.Kure is thr balance ed two specimens of pipe which the firm states is removed from the ground .Ml dti' them. which greatly interested There was some* ques- board members. One of thf tion as to the bond require- specimens was of pipe laid ment in cases of default in the ground 85 years ago. -

Baseball News Clippings

! BASEBALL I I I NEWS CLIPPINGS I I I I I I I I I I I I I BASE-BALL I FIRST SAME PLAYED IN ELYSIAN FIELDS. I HDBOKEN, N. JT JUNE ^9f }R4$.* I DERIVED FROM GREEKS. I Baseball had its antecedents In a,ball throw- Ing game In ancient Greece where a statue was ereoted to Aristonious for his proficiency in the game. The English , I were the first to invent a ball game in which runs were scored and the winner decided by the larger number of runs. Cricket might have been the national sport in the United States if Gen, Abner Doubleday had not Invented the game of I baseball. In spite of the above statement it is*said that I Cartwright was the Johnny Appleseed of baseball, During the Winter of 1845-1846 he drew up the first known set of rules, as we know baseball today. On June 19, 1846, at I Hoboken, he staged (and played in) a game between the Knicker- bockers and the New Y-ork team. It was the first. nine-inning game. It was the first game with organized sides of nine men each. It was the first game to have a box score. It was the I first time that baseball was played on a square with 90-feet between bases. Cartwright did all those things. I In 1842 the Knickerbocker Baseball Club was the first of its kind to organize in New Xbrk, For three years, the Knickerbockers played among themselves, but by 1845 they I had developed a club team and were ready to meet all comers. -

May 11, 2015 Plan to Attend

FRIDAY, MAY 8, 2015 ©2015 HORSEMAN PUBLISHING CO., LEXINGTON, KY USA • FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION CALL (859) 276-4026 Market Share Bears Watching In Debut As an undefeated (five-for-five) 2 year old Market Share obvi- PLAN TO ATTEND ously won his first start of the year. But since then trainer Linda Toscano has continued to annually have her star trotter ready right out of the box. Over the subsequent three years, Market Share has gone on to win his first start at three, four and five, and Toscano hopes the same holds true this year at six, al- though she admits it’s the sec- ond start she’s really eyeing. Market Share will start from MAY 11, 2015 post 4 in Race 6 Saturday Joseph Kyle Photo Kyle Joseph night at the Meadowlands, a 382 ENTRIES! Racehorses, racing prospects, $50,000 prep race for the broodmares, foals, yearlings & more! Arthur J. Cutler Memorial. Online catalog available at With just 10 entries for the www.bloodedhorse.com Cutler, no elims were needed, so race secretary Peter Koch instead carded a prep event for all the entries, who all come back for the “This is an important $175,000 (est.) Cutler final on “There’s No Substitute for Experience” race because it’s his Saturday, May 16. INQUIRIES TO ANY ONE OF THESE: first start, but it’s “In the scheme of things JERRY HAWS • P.O. Box 187 • Wilmore, Kentucky 40390 an unimportant race this is an important race be- Phone: (859) 858-4415 • Fax: (859) 858-8498 because next week cause it’s his first start, but it’s CHARLES MORGAN (937) 947-1218 is more important.” an unimportant race because DEAN BEACHY & ASSOCIATES next week is more important,” Auctioneers –Linda Toscano said Toscano. -

Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture James

The Communal Legitimacy of Collective Violence: Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture by James Peter Phelan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©James Phelan, 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the influences that New York City‘s Irish-Americans had on the violence, politics, and underground subcultures of the antebellum era. During the Great Famine era of the Irish Diaspora, Irish-Americans in Five Points, New York City, formed strong community bonds, traditions, and a spirit of resistance as an amalgamation of rural Irish and urban American influences. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Irish immigrants and their descendants combined community traditions with concepts of American individualism and upward mobility to become an important part of the antebellum era‘s ―Shirtless Democracy‖ movement. The proto-gang political clubs formed during this era became so powerful that by the late 1850s, clashes with Know Nothing and Republican forces, particularly over New York‘s Police force, resulted in extreme outbursts of violence in June and July, 1857. By tracking the Five Points Irish from famine to riot, this thesis as whole illuminates how communal violence and the riots of 1857 may be understood, moralised, and even legitimised given the community and culture unique to Five Points in the antebellum era. iii Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Faculty Publications and Other Works by History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Department 3-2019 Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting Elliot Gorn Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Gorn, Elliot. Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Boxing, , : 34-51, 2019. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications and Other Works by Department at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Cambridge University Press, 2019. 34 2 ELLIOTT J. GORN The Bare- Knuckle Era Origins of the Ring Fistic combat goes back at least as far as ancient Greece and Rome. Pindar , in 474 BC , celebrated Diagoras ’ victory in the Greek Olympiad: “But do thou, O father Zeus, that rulest over the height of Atabyrium, grant honour to the hymn ordained in praise of an Olympian victor, and to the hero who hath found fame for his prowess as a boxer; and do though give him grace and reverence in the eyes of citizens and of strangers too. For he goeth in a straight course along a path that hateth insolence.” Worthy of Zeus’ blessing, the successful boxer was a man of moral as well as physical excel- lence. -

The Conestoga Horse by JOHN STROHM (1793-1884) and HERBERT H

The Conestoga Horse By JOHN STROHM (1793-1884) AND HERBERT H. BECK. The Conestoga horse and the Conestoga wagon were evolved in and about that part of southeastern Pennsylvania which, before it was named Lancaster County, was known as Conestoga. The region was named for a river that has its main springhead in Turkey Hill, Caernarvon Township, whencc it crosses the Berks County line for a short distance and then returns into Lan- caster County to cross it, in increasing volume, passing the county seat, to flow between Manor and Conestoga townships into the Susquehanna. The names Conestoga and Lancaster County are inseparably connected in historical records. Unlike the Conestoga wagon, which was known under that name as early as 1750,1 and whose fame still lives in history and in actual form in museums, the Conestoga horse—a thing of flesh—was not preserved and is now nearly forgotten. The undoubted fact that the Conestoga horse was famous in its day and way warrants a compilation of available records of that useful animal. Nor could this subject be more fittingly treated in any other community than in the Conestoga Valley. The writer qualifies himself for his subject by the statement that he has been a horseman most of his life; that he has driven many hundreds of miles in buggy, runabout and sleigh; and ridden many thousands of miles on road and trail, and in the hunting field and the show ring. Between 1929 and 1940 he was riding master at Linden Hall School for Girls at Lititz, where he Instituted and carried on an annual horse show. -

South Amboy **** Sayreville

THE SOUTH AMBOY ★★★★ SAYREVILLE Date: August 24, 2013 PRICELESS Vol. 22 Issue 11 Former Police Chief 4-Year Old Remembered South Amboy By Tom Burkard Douglas A. Sprague, 84, of Morgan, Boy Remembered who was the Borough of Sayreville Chief of By Steve Schmid Police for many years, passed away on Aug. The Sacred Heart School community 7. He joined the Sayreville Police Dept. on is mourning the loss of 4-year old Kyrillos June 18, 1952 as a Patrolman, and was ap- Gendy. Police say he was killed crossing pointed Sergeant on June 23, 1958. Sprague Richmond Ave. August 9 in Staten Island, by was promoted to Captain of Detectives on a hit and run driver, who was charged with Feb. 20, 1963. He continued to advance in leaving the scene of an accident, resulting in rank, and on Feb. 28, 1977, was appointed the death, and 2 counts of leaving the scene Deputy Chief of Police. Sprague moved into of an accident resulting in serious injury. the top slot as Chief of Police on June 16, Also injured was his mother, Arini Thomas, 1984, serving through July 1, 1997. 34, and his sister Gabriella, 9. They were A 1946 Sayreville High School gradu- returning from a prayer service at a relative’s ate, he was an all-around athlete, and fol- lowing graduation served in the U.S. Navy Pictured is the huge crowd at the 14th Annual Antique & Classic Car Show on Broadway home in Staten Island. from 1948-1950 aboard the USS Des Moines. in South Amboy, which was sponsored by Independence Engine & Hose Co. -

Item No. 1 Andrew Jackson “Knows No Law but His Own Will”

Item No. 1 Andrew Jackson “Knows No Law but His Own Will” 1. [1828 Elections: Maine]: PENOBSCOT COUNTY ADMINISTRATION CONVENTION. [Bangor? 1828]. Folio broadside, 9-1/4" x 20". Matted, hinged at upper edge. Printed in three full columns. A few old folds, Very Good. The Convention met in Bangor on July 9, 1828. After endorsing candidates for various State offices, the Convention issued and printed its 'Address... to the Electors of the Counties of Somerset and Penobscot', focusing on the upcoming presidential contest. Praising the incumbent, John Quincy Adams, the Address proclaims, "It is sufficient to say of him, that talents of the highest order are joined to uncommon attainments... We would ask you to turn from the rantings of demagogues, the bold fictions of an irresponsible press... Is not our country moving on peacefully and prosperously in the great march of improvement?" Adams's opponent, General Jackson, is unsuited for the presidency: "His character has been formed as a military chieftain... He is rash, headstrong, impetuous and unreflecting-- that he knows no law but his own will." Example after example demonstrates Jackson's unfitness Not in American Imprints, Sabin, Wise & Cronin [Jackson, Adams], or on online sites of OCLC, AAS, Harvard, Boston Athenaeum, Bowdoin, U Maine as of July 2018. $850.00 Item No. 2 “He Had a Reputation as a Man of Letters Which Had Gone Beyond Color Distinctions” 2. [Abolition] Brown, William Wells: A LECTURE DELIVERED BEFORE THE FEMALE ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY OF SALEM, AT LYCEUM HALL, NOV. 14, 1847. BY WILLIAM W. BROWN, A FUGITIVE SLAVE. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 12

Ill I a* .^V/Jl'« **« c* 'VSfef' ^ A* ,VyVA° <k ^ °o ** ^•/ °v™v v-^'y v^-\*° .. http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog12newy .or ..V" *7yf^ a I*'. *b^ ^ *^^ oV^sua- ^ THE NEW YORK ical and Biographical Record. Devoted to the Interests of American Genealogy and Biography. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XII., 1881. PUBLISHED FOR THE SOCIETY, Mott Memorial Hall, No. 64 Madison Avenue, New Yopk. City. 4116 PUBLICATION "COMMITTEE. SAMUEL. S. PURPLE, JOHN J. LATTING, CHARLES B. MOORE, BEVERLEY R. BETTS. Mott Memorial Hall, 64 Madison Avenue. , INDEX TO SUBJFXTS. Abstracts of Brookhaven, L. I., Wills, by TosephP H Pettv a« ,«9 Adams, Rev. William, D.D., lk Memorial, by R ev ; E £' &2*>» •*"•*'>D D 3.S Genealogy, 9. Additions and Corrections to History of Descendants of Tames Alexander 17 Alexander, James and his Descendants, by Miss Elizabeth C. Tay n3 60 11 1 .c- ' 5 > Genealogy, Additions * ' ' 13 ; and Corrections to, 174. Bergen, Hon. Tennis G, Brief Memoir of Life and Writings of, by Samuel S. Purple, " Pedigree, by Samuel S. Purple, 152 Biography of Rev. William Adams, D.D., by Rev E ' P Rogers D D e of Elihu Burrit, 8 " 5 ' by William H. Lee, 101. ' " of Hon. Teunis G. Bergen, by Samuel S. Purple M D iao Brookhaven, L. I., Wills, Abstracts of/by Joseph H. Pe»y, 46, VoS^' Clinton Family, Introductory Sketch to History of, by Charles B. Moore, 195. Dutch Church Marriage Records, 37, 84, 124, 187. Geneal e n a io C°gswe 1 Fami 'y. H5; Middletown, Ct., Families, 200; pfi"ruynu vV family,Fa^7v ^49; %7Titus Pamily,! 100. -

The Maine Horse Breeders' Monthly, January 1883

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1-1883 The Maine Horse Breeders' Monthly, January 1883 J. W. Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDITED AND PUBLISHED BY J. W. THOMPSON, Canton, Me., U. S. A. —(o)— Terms, $1.00 per annum, in advance. Single Copies, 10 Cents. Vol. V. - No. I. JANUARY, 1883. Entered at the Post Office at Canton, Me., as Second Class Matter. ADVERTISEMENTS. First Annual Renewal of the MAINE HORSE BREEDERS’ PEARL's TROTTING STAKES. WHITE Open to all Colts and Fillies bred or GLYCERINE BEAUTIFIES THE COMPLEXION, owned in Maine. CURES ALL KINDS OF SKIN DISEASES, No. 1. Annual Nursery Stakes, tor two year REMOVES FRECKLES, MOTH old colts and fillies, foals of 1881, to be trotted in Aug. PATCHES, TAN, BLACK-WORMS, 1882. Mile beats, two in three to harness; $25.00 en and all Impurities, either within or upon the skin. trance. $5 to accompany the nomination, $10 to be paid For CHAPPED HANDS, ROUGH OR CHAFED SKIN it is June 1, 1883, and the remaining $10 Aug. 1, 1883. Ten or more nominations to fill. Entries to close April 1, indispensible. Try one bottle and you will never be 1883. without it. Use also No. -

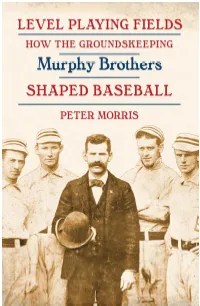

Level Playing Fields

Level Playing Fields LEVEL PLAYING FIELDS HOW THE GROUNDSKEEPING Murphy Brothers SHAPED BASEBALL PETER MORRIS UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS LINCOLN & LONDON © 2007 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska ¶ All rights reserved ¶ Manufactured in the United States of America ¶ ¶ Library of Congress Cata- loging-in-Publication Data ¶ Li- brary of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data ¶ Morris, Peter, 1962– ¶ Level playing fields: how the groundskeeping Murphy brothers shaped baseball / Peter Morris. ¶ p. cm. ¶ Includes bibliographical references and index. ¶ isbn-13: 978-0-8032-1110-0 (cloth: alk. pa- per) ¶ isbn-10: 0-8032-1110-4 (cloth: alk. paper) ¶ 1. Baseball fields— History. 2. Baseball—History. 3. Baseball fields—United States— Maintenance and repair. 4. Baseball fields—Design and construction. I. Title. ¶ gv879.5.m67 2007 796.357Ј06Ј873—dc22 2006025561 Set in Minion and Tanglewood Tales by Bob Reitz. Designed by R. W. Boeche. To my sisters Corinne and Joy and my brother Douglas Contents List of Illustrations viii Acknowledgments ix Introduction The Dirt beneath the Fingernails xi 1. Invisible Men 1 2. The Pursuit of Pleasures under Diffi culties 15 3. Inside Baseball 33 4. Who’ll Stop the Rain? 48 5. A Diamond Situated in a River Bottom 60 6. Tom Murphy’s Crime 64 7. Return to Exposition Park 71 8. No Suitable Ground on the Island 77 9. John Murphy of the Polo Grounds 89 10. Marlin Springs 101 11. The Later Years 107 12. The Murphys’ Legacy 110 Epilogue 123 Afterword: Cold Cases 141 Notes 153 Selected Bibliography 171 Index 179 Illustrations following page 88 1.