Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Hackenschmidt Vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd the University of Texas

Iron Game History Volume 11 Number 2 George Hackenschmidt vs. Frank Gotch Media Representations and the World Wrestling Title of 1908 Kim Beckwith & Jan Todd The University of Texas International wrestling star, George Hacken- stories about and a constituent of that world, an element schmidt, widely known as "The Russian Lion," met the of the story." The reporter, they argue, "not only relates American champion, Frank Gotch, at Chicago's Dexter stories but makes them."2 Similarly, pop culture analyst Park Amphitheater on April 3, 1908, in a wrestling title Carlin Romano contends that journalism is not a "minor bout that was labeled "The Athletic Contest of the Cen- placed before reality," but a "coherent nanative of the tmy" on the cover of the match program.' After three world that serves a particular purpose."3 Thinking about preliminary bouts, the much anticipated World's Heavy- journalism in light of this definition makes it easier to weight Wrestling Championships in the catch-as-catch- understand how in the days following the historic Gotch can style began at approximately 10:30 P.M. More than Hackenschmidt bout such different tales would be told two hours later, reporters ...-------------------. by various journalists even scrambled to file their stories in though all of them had watched the early hours of the morning SOUVENIR PROGRAM the same spmting event. Like and share their ringside intelli- 'f the characters in John Godfrey gence with an anxiously await- The Athletic Contest of Saxes's poem, "The Blind Men ing nation and world. The news the Century and the Elephant," almost all they sent out from Chicago, _ For •h• _ of the reporters who pe1111ed however, was totally unexpect- WORLD'S WRESTLING their reports from Chicago had ed. -

Rules and Regulations

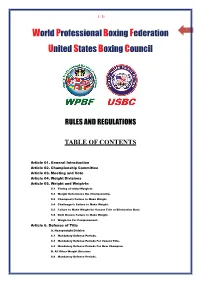

1 / 21 World Professional Boxing Federation 1 United States Boxing Council RULES AND REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Article 01. General Introduction Article 02. Championship Committee Article 03. Meeting and Vote Article 04. Weight Divisions Article 05. Weight and Weigh-In 5.1 Timing of Initial Weigh-In 5.2 Weight Determines the Championship. 5.3 Champion's Failure to Make Weight. 5.4 Challenger's Failure toMake Weight. 5.5 Failure to Make Weight for Vacant Title or Elimination Bout. 5.6 Both Boxers Failure to Make Weight. 5.7 Weigh-ins For Postponement. Article 6. Defense of Title A. Heavyweight Division 6.1 Mandatory Defense Periods. 6.2 Mandatory Defense Periods For Vacant Title. 6.3 Mandatory Defense Periods For New Champion. B. All Other Weight Divisions 6.4 Mandatory Defense Periods. 2 / 21 6.5 Mandatory Defense Periods For Vacant Title. 2 6.6 Mandatory Defense Periods For New Champion. 6.7 Voluntary Defense. 6.8 Time Limitations. 6.9 Notice of Mandatory Defense. Article 7. Leading Available Contender Article 8. Failure of Champion to Fulfill Contract and Rules Article 9. Unsanctioned Championship or Non-Championship Bout Article 10. Procedure When Title Is Declared Vacant Article 11. Draw Decision Article 12. Rematch Article 13. Disqualification Article 14. Return Bouts Article 15. Purse Bid Procedures 15.1 Call For Purse Bid. 15.2 Notification of Purse Bid. 15.3 Promoter's Obligation. 15.4 Form of Purse Bid. 15.5 Contents of Purse Bid. 15.6 Minimum Purse Bids. 15.7 Winning Bidder. 15.8 Non-Transfer. 15.9 Purse Offer Contracts. -

The Safety of BKB in a Modern Age

The Safety of BKB in a modern age Stu Armstrong 1 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© www.stuarmstrong.com Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 The Author .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Why write this paper? ......................................................................................................................... 3 The Safety of BKB in a modern age ................................................................................................... 3 Pugilistic Dementia ............................................................................................................................. 4 The Marquis of Queensbury Rules’ (1867) ......................................................................................... 4 The London Prize Ring Rules (1743) ................................................................................................. 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 8 2 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© -

State Athletic Commission 10/25/13 523

523 CMR: STATE ATHLETIC COMMISSION Table of Contents Page (523 CMR 1.00 THROUGH 4.00: RESERVED) 7 523 CMR 5.00: GENERAL PROVISIONS 31 Section 5.01: Definitions 31 Section 5.02: Application 32 Section 5.03: Variances 32 523 CMR 6.00: LICENSING AND REGISTRATION 33 Section 6.01: General Licensing Requirements: Application; Conditions and Agreements; False Statements; Proof of Identity; Appearance Before Commission; Fee for Issuance or Renewal; Period of Validity 33 Section 6.02: Physical and Medical Examinations and Tests 34 Section 6.03: Application and Renewal of a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.04: Initial Application for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant New to Massachusetts 35 Section 6.05: Application by an Amateur for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.06: Application for License as a Promoter 36 Section 6.07: Application for License as a Second 36 Section 6.08: Application for License as a Manager or Trainer 36 Section 6.09: Manager or Trainer May Act as Second Without Second’s License 36 Section 6.10: Application for License as a Referee, Judge, Timekeeper, and Ringside Physician 36 Section 6.11: Application for License as a Matchmaker 36 Section 6.12: Applicants, Licensees and Officials Must Submit Material to Commission as Directed 36 Section 6.13: Grounds for Denial of Application for License 37 Section 6.14: Application for New License or Petition for Reinstatement of License after Denial, Revocation or Suspension 37 Section 6.15: Effect of Expiration of License on -

Ohio Athletic Commission

Redbook LBO Analysis of Executive Budget Proposal Ohio Athletic Commission Shannon Pleiman, Senior Budget Analyst February 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Quick look... .......................................................................................................................... 1 Agency overview ................................................................................................................... 1 Analysis of FY 2022-FY 2023 budget proposal ......................................................................... 2 Operating statistics ......................................................................................................................... 2 Fee structure .............................................................................................................................. 2 Revenues .................................................................................................................................... 2 LBO Redbook Ohio Athletic Commission Quick look... The Ohio Athletic Commission (ATH) regulates boxing, mixed martial arts, professional wrestling, kickboxing, karate, and tough person contests, overseeing 1,200 competitors, promoters, officials, other event personnel, and athlete agents in these sports. A five-member board governs the Commission. Day-to-day operations are managed by two full-time employees and one part-time employee. The Commission is fully supported by fees and receives no GRF funding. The executive budget recommendations total approximately $556,000 over the -

CHAPTER 165-X-8 Professional Bare

165-X-8-.01. Definitions., AL ADC 165-X-8-.01 Alabama Administrative Code Alabama Athletic Commission Chapter 165-X-8. Professional Bare-Knuckle Boxing Ala. Admin. Code r. 165-X-8-.01 165-X-8-.01. Definitions. Currentness (1) “Applicant” means any persons, corporations, organizations or associations required to be licensed before promoting, holding, organizing, participating in, or competing in a professional boxing match, contest, or exhibition. (2) “Body jewelry” means any tangible object affixed to, through, or around any portion of the contestant's body. (3) “Official” unless otherwise indicated is an exclusive term collectively meaning “judge,” “referee,” “timekeeper,” and “inspectors” (4) “Sanctioning Organization” means a national or international organization generally recognized in the bare-knuckle boxing community and which: ranks bare-knuckle boxers within each weight class; sanctions and approves championship matches in those weight classes; and awards championship status and championship prizes (belts, rings, plaques, etc.) to the winner of those matches. (5) “Special Event” means a bare-knuckle boxing card or bare-knuckle boxing show, which has among its contests a championship match, a pay-per-view or subscription television match, a national televised match, or any other match of significance to boxing in this state as designated by the commission. (6) “The Commission” is reference for the Alabama Athletic Commission. Authors: Dr. John Marshall, Joel R. Blankenship, Larry Bright, Stan Frierson, Shane Sears Credits Statutory Authority: Code of Ala. 1975, § 41-9-1024. History: New Rule: Filed July 16, 2010; effective August 20, 2010. Repealed: Filed December 27, 2013; effective January 31, 2014. New Rule: Published February 28, 2020; effective April 13, 2020. -

Rules and Regulations of the World Boxing

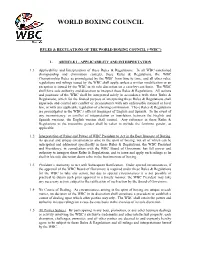

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL RULES & REGULATIONS OF THE WORLD BOXING COUNCIL (“WBC”) 1. ARTICLE I - APPLICABILITY AND INTERPRETATION 1.1 Applicability and Interpretation of these Rules & Regulations. In all WBC-sanctioned championship and elimination contests, these Rules & Regulations, the WBC Championship Rules as promulgated by the WBC from time to time, and all other rules, regulations and rulings issued by the WBC shall apply, unless a written modification or an exception is issued by the WBC in its sole discretion on a case-by-case basis. The WBC shall have sole authority and discretion to interpret these Rules & Regulations. All actions and positions of the WBC shall be interpreted solely in accordance with these Rules & Regulations, which for the limited purpose of interpreting these Rules & Regulations shall supersede and control any conflict or inconsistency with any enforceable national or local law, or with any applicable regulation of a boxing commission. These Rules & Regulations are promulgated in the WBC’s official languages of English and Spanish. In the event of any inconsistency, or conflict of interpretation or translation, between the English and Spanish versions, the English version shall control. Any reference in these Rules & Regulations to the masculine gender shall be taken to include the feminine gender, as applicable. 1.2 Interpretation of Rules and Power of WBC President to Act in the Best Interests of Boxing. As special and unique circumstances arise in the sport of boxing, not all of which can be anticipated and addressed specifically in these Rules & Regulations, the WBC President and Presidency, in consultation with the WBC Board of Governors, has full power and authority to interpret these Rules & Regulations, and to issue and apply such rulings as he shall in his sole discretion deem to be in the best interests of boxing. -

Boxing Gloves. Complete, Nith Rubber Cord and Fittings

t TENCINC REQUISITES FOILS. SUPERIOR SOLINGEN BLADES. FENCING MASKS; SINGLE STICKS. \ F. H,.AYRES, CITY SALE AND EXCHANGE WINSLOW’S ROLLER SKATES. 6‘ ADJUSTABLE.’’ p er pair. 1/11 per Doxwood Wheels, 4/6 per pair. Postage 4k -7 Bearing, IMl dltto, Bus\~uod Wheel\, I.adie5’ or tients’, IRON DUMB BELLS, 9/9, 10/9, 19j6 per pair. Any weight, Pustage 4d under IO/-. (‘1111b (‘olortrs to Order. I!STlhlATBS FREE. p’#¡ Photographic Apparatus, And every Requisite f,r the Gymnasium,Boxing, Running, Cycling, Cricket, Tennis,Croquet, ANI) ALI. Y ._-.. b. W. CAMACE, LTD., A. W. CAMAGE, LTD., LargestCycling and AthleticOutfitters largest Cycling and AthleticOutfitters IN THE WORLD. IN THE WORLD. REQUISITES FORCYCLING, CRICKET, TENNIS, GOLF, REQUISITESFOR CYCLING, CRICKET, TENNIS, GOLF, HOCKEY, FISHING,PHOTOGRAPHY, &c. HOCKEY, FISHING,PHOTOGRAPHY, &c. BILLIARDS,BAGATELLE, ROULETTE, CHESS, BILLIARDS,BAGATELLE, ROULETTE, CHESS, DOMINOES,DRAUGHTS, PLAYING CARDS, DOMINOES,DRAUGHTS, PLAYING CARDS, AND INDOORGAMES OFALL KINDS. AND INDOORGAMES OF ALLKINDS. ’ Writefor Gelteral Catalogue, coltlairring 4000 lllustralioiolts, post fre. THE“REFEREE” PUNCHINGBALL, or PHYSICALTRAINER. “Referee” Boxing Gloves. Complete, nith Rubber Cord and Fittings. THE MOST PEßFECT GLOVE No. 5. 28 in. 6. 30 in. 7. 32 in. 8. 34 in. g. 36 in. IN YEN TED. 1716 201- 2216 261- 301- 261- 2216 201- 1716 SPECIALCHEAP QUALITIES. The formation of the Glove is so arranged thatthe padding is broughtover from No. 5, Complete, lOj6 and 13/6 ; Large Size, 17j6. the back of the hand to the inside of the fingers, passing over the tipsof the same, PORTABLE STRIKING BAG. and extendingto above thesecond joints. No. -

This Week in Saratoga County History

This Week in Saratoga County History - The Death of John Morrissey Submitted by Charlie Kuenzel May 7, 2020 Charlie Kuenzel taught at Saratoga High School for 36 years and was co-owner of Saratoga Tours LLC for 19 years. Author, lecturer and currently President of Saratoga Springs History Museum, Charlie loves Saratoga History and can be reached at [email protected] During the 1800’s, Saratoga Springs became the number one tourist destination for summer visitors in the United States. Although the reputation of Saratoga Springs was originally built on health practices using the many mineral springs, it was further enhanced with the addition of thoroughbred horse racing and casino gambling. The one single person responsible for the introduction of those new activities was John Morrissey. May 1st each year is the anniversary of his death in Saratoga history. Morrissey was born in Ireland in 1831 and at about age 2 the family moved to Troy N.Y. Morrissey went to work at the age of 12, being employed at many factories. At 17 he started working on a steamship that made daily runs from Albany to New York City and married the ship captain’s daughter, Sarah Smith in 1849. Together they had one child, a son. The 1849 California Gold Rush lured him to San Francisco in 1851 were he never made any money as a prospector but became a very successful gambler. In 1852 he tried testing his boxing skills and defeated George Thompson in California for a $5,000 prize. Morrissey then returned to New York to schedule a fight with Yankee Sullivan and at one time was World Heavyweight Champ. -

Inertial Sensors for Performance Analysis in Combat Sports: a Systematic Review

sports Article Inertial Sensors for Performance Analysis in Combat Sports: A Systematic Review Matthew TO Worsey , Hugo G Espinosa * , Jonathan B Shepherd and David V Thiel School of Engineering and Built Environment, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD 4111, Australia; matthew.worsey@griffithuni.edu.au (M.T.O.W.); j.shepherd@griffith.edu.au (J.B.S.); d.thiel@griffith.edu.au (D.V.T.) * Correspondence: h.espinosa@griffith.edu.au; Tel.: +61-7-3735-8432 Received: 5 December 2018; Accepted: 18 January 2019; Published: 21 January 2019 Abstract: The integration of technology into training and competition sport settings is becoming more commonplace. Inertial sensors are one technology being used for performance monitoring. Within combat sports, there is an emerging trend to use this type of technology; however, the use and selection of this technology for combat sports has not been reviewed. To address this gap, a systematic literature review for combat sport athlete performance analysis was conducted. A total of 36 records were included for review, demonstrating that inertial measurements were predominately used for measuring strike quality. The methodology for both selecting and implementing technology appeared ad-hoc, with no guidelines for appropriately analysing the results. This review summarises a framework of best practice for selecting and implementing inertial sensor technology for evaluating combat sport performance. It is envisaged that this review will act as a guide for future research into applying technology to combat sport. Keywords: combat sport; technology; inertial sensor; performance 1. Introduction In recent years, technological developments have resulted in the production of small, unobtrusive wearable inertial sensors. -

Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture James

The Communal Legitimacy of Collective Violence: Community and Politics in Antebellum New York City Irish Gang Subculture by James Peter Phelan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©James Phelan, 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the influences that New York City‘s Irish-Americans had on the violence, politics, and underground subcultures of the antebellum era. During the Great Famine era of the Irish Diaspora, Irish-Americans in Five Points, New York City, formed strong community bonds, traditions, and a spirit of resistance as an amalgamation of rural Irish and urban American influences. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Irish immigrants and their descendants combined community traditions with concepts of American individualism and upward mobility to become an important part of the antebellum era‘s ―Shirtless Democracy‖ movement. The proto-gang political clubs formed during this era became so powerful that by the late 1850s, clashes with Know Nothing and Republican forces, particularly over New York‘s Police force, resulted in extreme outbursts of violence in June and July, 1857. By tracking the Five Points Irish from famine to riot, this thesis as whole illuminates how communal violence and the riots of 1857 may be understood, moralised, and even legitimised given the community and culture unique to Five Points in the antebellum era. iii Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

Ibf/Usba Rules Governing Championship Contests

IBF/USBA RULES GOVERNING CHAMPIONSHIP CONTESTS Effective September 1, 2006 with amendments of October 21, 2010, February 25, 2011, October 7, 2011, December 2, 2011, April 18, 2013, October 17, 2013, and January 27, 2014. Posted and Effective: January 29, 2014 International Boxing Federation/United States Boxing Association 899 Mountain Ave., Suite 2C Springfield, NJ 07081 Phone: (973)564-8046 Fax: (973)564-8751 IBF/USBA RULES GOVERNING CHAMPIONSHIP CONTESTS Table of Contents Rule Page 1. Weight and Weigh-Ins ..................................................................................................... 1 A. Timing of Initial Weigh-In ...................................................................................... 2 1. Champion’s Failure to Make Weight .......................................................... 2 2. Challenger’s Failure to Make Weight ......................................................... 2 3. Failure to Make Weight in Fight for Vacant Title or Elimination Bout ...... 2 4. Both Boxers’ Failure to Make Weight ........................................................ 2 B. Timing of Second Day Weigh-In ............................................................................ 2 1. Champion’s Failure to Make Weight or to Appear for the Second Day Weigh-In ...................................................................................................... 3 2. Challenger’s Failure to Make Weight or to Appear for the Second Day Weigh-In .....................................................................................................