Identification of Acquired Copy Number Alterations and Uniparental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

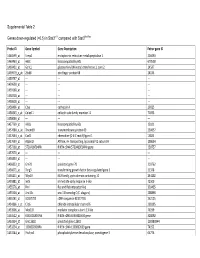

Table 2. Functional Classification of Genes Differentially Regulated After HOXB4 Inactivation in HSC/Hpcs

Table 2. Functional classification of genes differentially regulated after HOXB4 inactivation in HSC/HPCs Symbol Gene description Fold-change (mean ± SD) Signal transduction Adam8 A disintegrin and metalloprotease domain 8 1.91 ± 0.51 Arl4 ADP-ribosylation factor-like 4 - 1.80 ± 0.40 Dusp6 Dual specificity phosphatase 6 (Mkp3) - 2.30 ± 0.46 Ksr1 Kinase suppressor of ras 1 1.92 ± 0.42 Lyst Lysosomal trafficking regulator 1.89 ± 0.34 Mapk1ip1 Mitogen activated protein kinase 1 interacting protein 1 1.84 ± 0.22 Narf* Nuclear prelamin A recognition factor 2.12 ± 0.04 Plekha2 Pleckstrin homology domain-containing. family A. (phosphoinosite 2.15 ± 0.22 binding specific) member 2 Ptp4a2 Protein tyrosine phosphatase 4a2 - 2.04 ± 0.94 Rasa2* RAS p21 activator protein 2 - 2.80 ± 0.13 Rassf4 RAS association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family 4 3.44 ± 2.56 Rgs18 Regulator of G-protein signaling - 1.93 ± 0.57 Rrad Ras-related associated with diabetes 1.81 ± 0.73 Sh3kbp1 SH3 domain kinase bindings protein 1 - 2.19 ± 0.53 Senp2 SUMO/sentrin specific protease 2 - 1.97 ± 0.49 Socs2 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 - 2.82 ± 0.85 Socs5 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 5 2.13 ± 0.08 Socs6 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 6 - 2.18 ± 0.38 Spry1 Sprouty 1 - 2.69 ± 0.19 Sos1 Son of sevenless homolog 1 (Drosophila) 2.16 ± 0.71 Ywhag 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5- monooxygenase activation protein. - 2.37 ± 1.42 gamma polypeptide Zfyve21 Zinc finger. FYVE domain containing 21 1.93 ± 0.57 Ligands and receptors Bambi BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor - 2.94 ± 0.62 -

A Comparative Analysis of Transcribed Genes in the Mouse Hypothalamus and Neocortex Reveals Chromosomal Clustering

A comparative analysis of transcribed genes in the mouse hypothalamus and neocortex reveals chromosomal clustering Wee-Ming Boon*, Tim Beissbarth†, Lavinia Hyde†, Gordon Smyth†, Jenny Gunnersen*, Derek A. Denton*‡, Hamish Scott†, and Seong-Seng Tan* *Howard Florey Institute, University of Melbourne, Parkville 3052, Australia; and †Genetics and Bioinfomatics Division, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Royal Parade, Parkville 3050, Australia Contributed by Derek A. Denton, August 26, 2004 The hypothalamus and neocortex are subdivisions of the mamma- representing all of the genes that are expressed (qualitative and lian forebrain, and yet, they have vastly different evolutionary quantitative) in the hypothalamus and neocortex under standard histories, cytoarchitecture, and biological functions. In an attempt conditions. to define these attributes in terms of their genetic activity, we have In the current study, we describe the use of the Serial Analysis compared their genetic repertoires by using the Serial Analysis of of Gene Expression (SAGE) database, which allows simulta- Gene Expression database. From a comparison of 78,784 hypothal- neous detection of the expression levels of the entire genome amus tags with 125,296 neocortical tags, we demonstrate that each without a priori knowledge of gene sequences (13). SAGE takes structure possesses a different transcriptional profile in terms of advantage of the fact that a small sequence tag taken from a gene ontological characteristics and expression levels. Despite its defined position within the transcript is sufficient to identify the more recent evolutionary history, the neocortex has a more com- gene (from known cDNA or EST sequences), and up to 40 tags plex pattern of gene activity. -

Cow's Milk Allergy in Dutch Children

Petrus et al. Clin Transl Allergy (2016) 6:16 DOI 10.1186/s13601-016-0105-z Clinical and Translational Allergy RESEARCH Open Access Cow’s milk allergy in Dutch children: an epigenetic pilot survey Nicole C. M. Petrus1*†, Peter Henneman2†, Andrea Venema2, Adri Mul2, Femke van Sinderen2, Martin Haagmans2, Olaf Mook2, Raoul C. Hennekam1,2, Aline B. Sprikkelman1‡ and Marcel Mannens2‡ Abstract Background: Cow’s milk allergy (CMA) is a common disease in infancy. Early environmental factors are likely to con- tribute to CMA. It is known that epigenetic gene regulation can be altered by environmental factors. We have set up a proof of concept study, aiming to detect epigenetic associations specific with CMA. Methods: We studied children from the Dutch EuroPrevall birth cohort study (N 20 CMA, N 23 controls, N 10 tolerant boys), age and gender matched. CMA was challenge proven. Bisulfite converted= DNA =(blood) was analyzed= using the 450K infinium DNA-methylation array. Four groups (combined, girls, boys and tolerant boys) were analysed between CMA and controls. Statistical analysis and pathway-analysis were performed in “R” using IMA, Minfi and the global-test package. Differentially methylated regions in DHX58, ZNF281, EIF42A and HTRA2 genes were validated by quantitative amplicon sequencing (ROCHE 454®). Results: General hypermethylation was found in the CMA group compared to control children, while this effect was absent in the tolerant group. Methylation differences were, among others, found in regions of DHX58, ZNF281, EIF42A and HTRA2 genes. Several of these genes are known to be involved in immunological pathways and associated with other allergies. Conclusion: We show that epigenetic associations are involved in CMA. -

The Role of Blm Helicase in Homologous Recombination, Gene Conversion Tract Length, and Recombination Between Diverged Sequences in Drosophila Melanogaster

| INVESTIGATION The Role of Blm Helicase in Homologous Recombination, Gene Conversion Tract Length, and Recombination Between Diverged Sequences in Drosophila melanogaster Henry A. Ertl, Daniel P. Russo, Noori Srivastava, Joseph T. Brooks, Thu N. Dao, and Jeannine R. LaRocque1 Department of Human Science, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC 20057 ABSTRACT DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are a particularly deleterious class of DNA damage that threatens genome integrity. DSBs are repaired by three pathways: nonhomologous-end joining (NHEJ), homologous recombination (HR), and single-strand annealing (SSA). Drosophila melanogaster Blm (DmBlm) is the ortholog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SGS1 and human BLM, and has been shown to suppress crossovers in mitotic cells and repair mitotic DNA gaps via HR. To further elucidate the role of DmBlm in repair of a simple DSB, and in particular recombination mechanisms, we utilized the Direct Repeat of white (DR-white) and Direct Repeat of white with mutations (DR-white.mu) repair assays in multiple mutant allele backgrounds. DmBlm null and helicase-dead mutants both demonstrated a decrease in repair by noncrossover HR, and a concurrent increase in non-HR events, possibly including SSA, crossovers, deletions, and NHEJ, although detectable processing of the ends was not significantly impacted. Interestingly, gene conversion tract lengths of HR repair events were substantially shorter in DmBlm null but not helicase-dead mutants, compared to heterozygote controls. Using DR-white.mu,we found that, in contrast to Sgs1, DmBlm is not required for suppression of recombination between diverged sequences. Taken together, our data suggest that DmBlm helicase function plays a role in HR, and the steps that contribute to determining gene conversion tract length are helicase-independent. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

0.5) in Stat3∆/∆ Compared with Stat3flox/Flox

Supplemental Table 2 Genes down-regulated (<0.5) in Stat3∆/∆ compared with Stat3flox/flox Probe ID Gene Symbol Gene Description Entrez gene ID 1460599_at Ermp1 endoplasmic reticulum metallopeptidase 1 226090 1460463_at H60c histocompatibility 60c 670558 1460431_at Gcnt1 glucosaminyl (N-acetyl) transferase 1, core 2 14537 1459979_x_at Zfp68 zinc finger protein 68 24135 1459747_at --- --- --- 1459608_at --- --- --- 1459168_at --- --- --- 1458718_at --- --- --- 1458618_at --- --- --- 1458466_at Ctsa cathepsin A 19025 1458345_s_at Colec11 collectin sub-family member 11 71693 1458046_at --- --- --- 1457769_at H60a histocompatibility 60a 15101 1457680_a_at Tmem69 transmembrane protein 69 230657 1457644_s_at Cxcl1 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 14825 1457639_at Atp6v1h ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit H 108664 1457260_at 5730409E04Rik RIKEN cDNA 5730409E04Rik gene 230757 1457070_at --- --- --- 1456893_at --- --- --- 1456823_at Gm70 predicted gene 70 210762 1456671_at Tbrg3 transforming growth factor beta regulated gene 3 21378 1456211_at Nlrp10 NLR family, pyrin domain containing 10 244202 1455881_at Ier5l immediate early response 5-like 72500 1455576_at Rinl Ras and Rab interactor-like 320435 1455304_at Unc13c unc-13 homolog C (C. elegans) 208898 1455241_at BC037703 cDNA sequence BC037703 242125 1454866_s_at Clic6 chloride intracellular channel 6 209195 1453906_at Med13l mediator complex subunit 13-like 76199 1453522_at 6530401N04Rik RIKEN cDNA 6530401N04 gene 328092 1453354_at Gm11602 predicted gene 11602 100380944 1453234_at -

Compound Heterozygosity for Novel Truncating Variants in the LMOD3 Gene As the Cause of Polyhydramnios in Two Successive Fetuses

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research @ Cardiff CASE REPORT published: 13 September 2019 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00835 Compound Heterozygosity for Novel Truncating Variants in the LMOD3 Gene as the Cause of Polyhydramnios in Two Successive Fetuses Ye Wang 1, Caixia Zhu 1, Liu Du 2, Qiaoer Li 3, Mei-Fang Lin 2, Claude Férec 4,5, David N. Cooper 6, Jian-Min Chen 4† and Yi Zhou 1*† 1 Fetal Medicine Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China, 2 Department of Ultrasonic Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China, 3 Jiangmen Central Hospital, Affiliated Jiangmen Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Jiangmen, China, 4 EFS, Univ Brest, Inserm, UMR 1078, GGB, Brest, France, 5 CHU Brest, Service de Génétique, Brest, France, 6Institute of Medical Genetics, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom Polyhydramnios is sometimes associated with genetic defects. However, establishing an Edited by: Fan Jin, accurate diagnosis and pinpointing the precise genetic cause of polyhydramnios in any Zhejiang University, China given case represents a major challenge because it is known to occur in association with Reviewed by: over 200 different conditions. Whole exome sequencing (WES) is now a routine part of Liang-Liang Fan, Central South University, China the clinical workup, particularly with diseases characterized by atypical manifestations and Wenbin Zou, significant genetic heterogeneity. Here we describe the identification, by means of WES, Changhai Hospital, China of novel compound heterozygous truncating variants in the LMOD3 gene [i.e., c.1412delA *Correspondence: (p.Lys471Serfs*18) and c.1283dupC (p.Gly429Trpfs*35)] in a Chinese family with two Yi Zhou [email protected] successive fetuses affected with polyhydramnios, thereby potentiating the prenatal diagnosis of nemaline myopathy (NM) in the proband. -

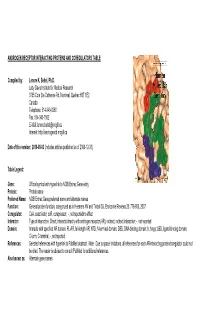

Androgen Receptor Interacting Proteins and Coregulators Table

ANDROGEN RECEPTOR INTERACTING PROTEINS AND COREGULATORS TABLE Compiled by: Lenore K. Beitel, Ph.D. Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research 3755 Cote Ste Catherine Rd, Montreal, Quebec H3T 1E2 Canada Telephone: 514-340-8260 Fax: 514-340-7502 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://androgendb.mcgill.ca Date of this version: 2010-08-03 (includes articles published as of 2009-12-31) Table Legend: Gene: Official symbol with hyperlink to NCBI Entrez Gene entry Protein: Protein name Preferred Name: NCBI Entrez Gene preferred name and alternate names Function: General protein function, categorized as in Heemers HV and Tindall DJ. Endocrine Reviews 28: 778-808, 2007. Coregulator: CoA, coactivator; coR, corepressor; -, not reported/no effect Interactn: Type of interaction. Direct, interacts directly with androgen receptor (AR); indirect, indirect interaction; -, not reported Domain: Interacts with specified AR domain. FL-AR, full-length AR; NTD, N-terminal domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; h, hinge; LBD, ligand-binding domain; C-term, C-terminal; -, not reported References: Selected references with hyperlink to PubMed abstract. Note: Due to space limitations, all references for each AR-interacting protein/coregulator could not be cited. The reader is advised to consult PubMed for additional references. Also known as: Alternate gene names Gene Protein Preferred Name Function Coregulator Interactn Domain References Also known as AATF AATF/Che-1 apoptosis cell cycle coA direct FL-AR Leister P et al. Signal Transduction 3:17-25, 2003 DED; CHE1; antagonizing regulator Burgdorf S et al. J Biol Chem 279:17524-17534, 2004 CHE-1; AATF transcription factor ACTB actin, beta actin, cytoplasmic 1; cytoskeletal coA - - Ting HJ et al. -

HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM 005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for RC201834 HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM_005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM_005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone Tag: Myc-DDK Symbol: HNRNPH1 Synonyms: hnRNPH; HNRPH; HNRPH1 Vector: pCMV6-Entry (PS100001) E. coli Selection: Kanamycin (25 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Neomycin This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 6 HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM_005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone – RC201834 ORF Nucleotide >RC201834 ORF sequence Sequence: Red=Cloning site Blue=ORF Green=Tags(s) TTTTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGGCCGGGAATTCGTCGACTGGATCCGGTACCGAGGAGATCTGCC GCCGCGATCGCC ATGATGTTGGGCACGGAAGGTGGAGAGGGATTCGTGGTGAAGGTCCGGGGCTTGCCCTGGTCTTGCTCGG CCGATGAAGTGCAGAGGTTTTTTTCTGACTGCAAAATTCAAAATGGGGCTCAAGGTATTCGTTTCATCTA CACCAGAGAAGGCAGACCAAGTGGCGAGGCTTTTGTTGAACTTGAATCAGAAGATGAAGTCAAATTGGCC CTGAAAAAAGACAGAGAAACTATGGGACACAGATATGTTGAAGTATTCAAGTCAAACAACGTTGAAATGG ATTGGGTGTTGAAGCATACTGGTCCAAATAGTCCTGACACGGCCAATGATGGCTTTGTACGGCTTAGAGG ACTTCCCTTTGGATGTAGCAAGGAAGAAATTGTTCAGTTCTTCTCAGGGTTGGAAATCGTGCCAAATGGG ATAACATTGCCGGTGGACTTCCAGGGGAGGAGTACGGGGGAGGCCTTCGTGCAGTTTGCTTCACAGGAAA TAGCTGAAAAGGCTCTAAAGAAACACAAGGAAAGAATAGGGCACAGGTATATTGAAATCTTTAAGAGCAG TAGAGCTGAAGTTAGAACTCATTATGATCCACCACGAAAGCTTATGGCCATGCAGCGGCCAGGTCCTTAT -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Genome-Wide Analysis of Androgen Receptor Binding and Gene Regulation in Two CWR22-Derived Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

Endocrine-Related Cancer (2010) 17 857–873 Genome-wide analysis of androgen receptor binding and gene regulation in two CWR22-derived prostate cancer cell lines Honglin Chen1, Stephen J Libertini1,4, Michael George1, Satya Dandekar1, Clifford G Tepper 2, Bushra Al-Bataina1, Hsing-Jien Kung2,3, Paramita M Ghosh2,3 and Maria Mudryj1,4 1Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of California Davis, 3147 Tupper Hall, Davis, California 95616, USA 2Division of Basic Sciences, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, Cancer Center and 3Department of Urology, University of California Davis, Sacramento, California 95817, USA 4Veterans Affairs Northern California Health Care System, Mather, California 95655, USA (Correspondence should be addressed to M Mudryj at Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of California, Davis; Email: [email protected]) Abstract Prostate carcinoma (CaP) is a heterogeneous multifocal disease where gene expression and regulation are altered not only with disease progression but also between metastatic lesions. The androgen receptor (AR) regulates the growth of metastatic CaPs; however, sensitivity to androgen ablation is short lived, yielding to emergence of castrate-resistant CaP (CRCaP). CRCaP prostate cancers continue to express the AR, a pivotal prostate regulator, but it is not known whether the AR targets similar or different genes in different castrate-resistant cells. In this study, we investigated AR binding and AR-dependent transcription in two related castrate-resistant cell lines derived from androgen-dependent CWR22-relapsed tumors: CWR22Rv1 (Rv1) and CWR-R1 (R1). Expression microarray analysis revealed that R1 and Rv1 cells had significantly different gene expression profiles individually and in response to androgen. -

1) (As of December 2018) and the Latest GWAS of AD (2

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES downstream intergenic ncRNA_exonic upstream ●936 ●918 group downstream intergenic ncRNA_exonic upstream group exonic exonicintronicintronic ncRNA_intronic ncRNA_intronicUTR3 UTR3 3.8% 1.2%1.5%1.9% 3.8% 5.4%5.4% 750 0.3% 3.8%1.2%1.5%1.9% ●700 5.4% ●670 0.3% 500 45.8% 40.240.2% % 45.8% ●329 ●274 250 ●223 Number (GWAS SNPs/studies) Number (GWAS ●128 ●105 45.8% ●54 ●57 ●58 ●48 ●42 ●46 ●50 ●30 ●3740.2% ● ●17 ●25 ●4 ●6 ●12 0 ● 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Year Supplementary Figure S1. GWAS of AD since 2007. The figure is based on data from the GWAS Catalog (1) (as of December 2018) and the latest GWAS of AD (2). The green area shows the total number of AD-associated SNPs, and the purple area shows the total number of GWAS of AD. The insert chart shows the proportions of different types of all 936 AD-associated SNPs. 1 100 200 RPS27A TGFB2 BIN1 C4BPB MSH2 PROC UGT1A1 RAB1A TTN DISC1 50 PDCL3 COL4A3 CD55 ERCC3 100 USP21 C4BPA ITSN2 PTPRF MPZ FMN2 INPP5D CEP85 FNBP1L CSF1 CD46 ADAMTS4 PRKRA SPRED2 0 CTNNA2 DGKD ADCY10 ZAP70 LIMS2 PDE1A PROX1 0 CHRNB2 CR1 HSPG2 SH3BGRL3 DAB1 CTBS FCER1G MAP3K2 AD risk score or log10(P value) IL6R CDC73 CD34 AD risk score or log10(P value) −50 B4GALT3 IL19 0 50 100 150 200 250 0 50 100 150 200 Chromosome 1 (Mb) Chromosome 2 (Mb) ATP2B2 LTF ARF4 MECOM PAK2 EPHB1 40 VHL PRSS42 ARL6IP5 150 COL25A1 TDGF1 RPSA CCR2 CCR1 IL1RAP IRAK2 20 PTPRG 100 FLNB TF CX3CR1 IL17RD SH3RF1 FGG FANCD2 LIMD1 CCR5 50 0 WDR1 PDGFRA EIF4E FGB AD risk score or log10(P value) AD risk