Outside Mute? Ut, No Wave and Blast First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

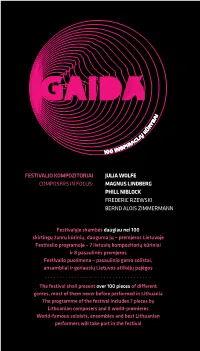

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Yazoo Discography

Yazoo discography This discography was created on basis of web resources (special thanks to Eugenio Lopez at www.yazoo.org.uk and Matti Särngren at hem.spray.se/lillemej) and my own collection (marked *). Whenever there is doubt whether a certain release exists, this is indicated. The list is definitely not complete. Many more editions must exist in European countries. Also, there must be a myriad of promo’s out there. I have only included those and other variations (such as red vinyl releases) if I have at least one well documented source. Also, the list of covers is far from complete and I would really appreciate any input. There are four sections: 1. Albums, official releases 2. Singles, official releases 3. Live, bootlegs, mixes and samples 4. Covers (Christian Jongeneel 21-03-2016) 1 1 Albums Upstairs at Eric’s Yazoo 1982 (some 1983) A: Don’t go (3:06) B: Only you (3:12) Too pieces (3:12) Goodbye seventies (2:35) Bad connection (3:17) Tuesday (3:20) I before e except after c (4:38) Winter kills (4:02) Midnight (4:18) Bring your love down (didn’t I) (4:40) In my room (3:50) LP UK Mute STUMM 7 LP France Vogue 540037 * LP Germany Intercord INT 146.803 LP Spain RCA Victor SPL 1-7366 Lyrics on separate sheet ‘Arriba donde Eric’ * LP Spain RCA Victor SPL 1-7366 White label promo LP Spain Sanni Records STUMM 7 Reissue, 1990 * LP Sweden Mute STUMM 7 Marked NCB on label LP Greece Polygram/Mute 4502 Lyrics on separate sheet * LP Japan Sire P-11257 Lyrics on separate sheets (english & japanese) * LP Australia Mute POW 6044 Gatefold sleeve LP Yugoslavia RTL LL 0839 * Cass UK Mute C STUMM 7 * Cass Germany Intercord INT 446.803 Cass France Vogue 740037 Cass Spain RCA Victor SPK1 7366 Reissue, 1990 Cass Spain Sanni Records CSTUMM 7 Different case sleeve Cass India Mute C-STUMM 7 Cass Japan Sire PKF-5356 Cass Czech Rep. -

The Menstrual Cramps / Kiss Me, Killer

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 279 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 “What was it like getting Kate Bush’s approval? One of the best moments ever!” photo: Oli Williams CANDYCANDY SAYSSAYS Brexit, babies and Kate Bush with Oxford’s revitalised pop wonderkids Also in this issue: Introducing DOLLY MAVIES Wheatsheaf re-opens; Cellar fights on; Rock Barn closes plus All your Oxford music news, previews and reviews, and seven pages of local gigs for October NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk host a free afternoon of music in the Wheatsheaf’s downstairs bar, starting at 3.30pm with sets from Adam & Elvis, Mark Atherton & Friends, Twizz Twangle, Zim Grady BEANIE TAPES and ALL WILL BE WELL are among the labels and Emma Hunter. releasing new tapes for Cassette Store Day this month. Both locally- The enduring monthly gig night, based labels will have special cassette-only releases available at Truck run by The Mighty Redox’s Sue Store on Saturday 13th October as a series of events takes place in record Smith and Phil Freizinger, along stores around the UK to celebrate the resurgence of the format. with Ainan Addison, began in Beanie Tapes release an EP by local teenage singer-songwriter Max October 1991 with the aim of Blansjaar, titled `Spit It Out’, as well as `Continuous Play’, a compilation recreating the spirit of free festivals of Oxford acts featuring 19 artists, including Candy Says; Gaz Coombes; in Oxford venues and has proudly Lucy Leave; Premium Leisure and Dolly Mavies (pictured). -

The Golden Age of Non-Idiomatic Improvisation

The Golden Age of Non-Idiomatic Improvisation FYS 129 David Keffer, Professor Dept. of Materials Science & Engineering The University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996-2100 [email protected] http: //cl ausi us.engr.u tk.e du / Various Quotes These slides contain a collection of some of the quotes largely from the musicians that are studied during the course. The idea is to present “musicians in their own words”. Thurston Moore American guitarist and vocalist (July 25, 1958—) Background on Sonic Youth Thurston Moore was a guitarist and vocalist for Sonic Youth. Sonic Youth was an American alternative rock band from New York City, formed in 1981. Their lineup largely consisted of Thurston Moore (guitar and vocals), Kim Gordon (bass guitar, vocals, and guitar), Lee Ranaldo (guitar and vocals), Steve Shelley (drums). In their early career, Sonic Youth was associated with the no wave art and music scene in New York City. Part of the first wave of American noise rock groups, the band carried out their interpretation of the hardcore punk ethos throughout the evolving American underground that focused more on the DIY ethic of the genre rather than its specific sound. As a result, some consider Sonic Youth as pivotal in the rise of the alternative rock and indie rock movementThbdts. The band exper ience d success an ditild critical acc lithhtlaim throughout their existence, continuing into the new millennium, including signing to major label DGC in 1990, and headlining the 1995 Lollapalooza festival. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonic_youth Moore Quotes Q: What led Sonic Youth to do a project like Goodbye 20th Century? Moore: It was definitely a universe or world that we were aware of. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene

NIGHTLIGHT: TRADITION AND CHANGE IN A LOCAL MUSIC SCENE Aaron Smithers A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum of Folklore. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Glenn Hinson Patricia Sawin Michael Palm ©2018 Aaron Smithers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron Smithers: Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene (Under the direction of Glenn Hinson) This thesis considers how tradition—as a dynamic process—is crucial to the development, maintenance, and dissolution of the complex networks of relations that make up local music communities. Using the concept of “scene” as a frame, this ethnographic project engages with participants in a contemporary music scene shaped by a tradition of experimentation that embraces discontinuity and celebrates change. This tradition is learned and communicated through performance and social interaction between participants connected through the Nightlight—a music venue in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any merit of this ethnography reflects the commitment of a broad community of dedicated individuals who willingly contributed their time, thoughts, voices, and support to make this project complete. I am most grateful to my collaborators and consultants, Michele Arazano, Robert Biggers, Dave Cantwell, Grayson Currin, Lauren Ford, Anne Gomez, David Harper, Chuck Johnson, Kelly Kress, Ryan Martin, Alexis Mastromichalis, Heather McEntire, Mike Nutt, Katie O’Neil, “Crowmeat” Bob Pence, Charlie St. Clair, and Isaac Trogden, as well as all the other musicians, employees, artists, and compatriots of Nightlight whose combined efforts create the unique community that define a scene. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Ladyslipper Tenth Anniversary

Ladyslipper Tenth Anniversary Resource Guide apes by Women T 1986 About Ladyslipper Ladyslipper is a North Carolina non-profit, tax- 1982 brought the first release on the Ladys exempt organization which has been involved lipper label: Marie Rhines/Tartans & Sagebrush, in many facets of women's music since 1976. originally released on the Biscuit City label. In Our basic purpose has consistently been to 1984 we produced our first album, Kay Gard heighten public awareness of the achievements ner/A Rainbow Path. In 1985 we released the of women artists and musicians and to expand first new wave/techno-pop women's music al the scope and availability of musical and liter bum, Sue Fink/Big Promise; put the new age ary recordings by women. album Beth York/Transformations onto vinyl; and released another new age instrumental al One of the unique aspects of our work has bum, Debbie Tier/Firelight Our purpose as a been the annual publication of the world's most label is to further new musical and artistic direc comprehensive Catalog and Resource Guide of tions for women artists. Records and Tapes by Women—the one you now hold in your hands. This grows yearly as Our name comes from an exquisite flower the number of recordings by women continues which is one of the few wild orchids native to to develop in geometric proportions. This anno North America and is currently an endangered tated catalog has given thousands of people in species. formation about and access to recordings by an expansive variety of female musicians, writers, Donations are tax-deductible, and we do need comics, and composers. -

Song List by Member

song artist album label dj year-month-order leaf house animal collective sung tongs 2004-08-02 bebete vaohora jorge ben the definitive collection 2004-08-08 amor brasileiro vinicius cantuaria tucuma 2004-08-09 crayon manitoba up in flames 2004-08-10 transit fennesz venice 2004-08-11 cold irons bound bob dylan time out of mind 2004-08-13 mini, mini, mini jacques dutronc en vogue 2004-08-14 unspoken four tet rounds 2004-08-15 dead homiez ice cube kill at will 2004-08-16 forever's no time at all pete townsend who came first 2004-08-17 mockingbird trailer bride hope is a thing with feathers 2004-08-18 call 1-800 fear lali puna faking the books 2004-08-19 vuelvo al sur gotan project la revancha del tango 2004-08-21 brick house commodores pure funk polygram tv adam 1998-10-09 louis armstrong - the jazz collector mack the knife louis armstrong edition laserlight adam 1998-10-18 harry and maggie swervedriver adam h. 2012-04-02 dust devil school of seven bells escape from desire adam h. 2012-04-13 come on my skeleton plug back on time adam h. 2012-09-05 elephant tame impala elephant adam h. 2012-09-09 day one toro y moi everything in return adam h. 2014-03-01 thank dub bill callahan have fun with god adam h. 2014-03-10 the other side of summer elvis costello spike warner bros. adam s (#2) 2006-01-04 wrong band tori amos under the pink atlantic adam s (#2) 2006-01-12 Baby Lemonade Syd Barrett Barrett Adam S. -

Download PDF Booklet

www.zerecords.com UNDER THE INFLUENCE / WHITE SPIRIT The 21st century has produced a new generation of young contenders of all kinds, who have, within months, spread a new string of names across the planet such as The Rapture, Playgroup, LCD Sound system, Liars, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Radio 4 and the likes, just to name a few. Once again the heat was initiated in NYC, even though its Lower East Side epicenter « cleaned up » by Giuliani and Bloomberg, has moved a few blocks east and across the river to Brooklyn and Williamsburg. It might be wise to remind the younger ones among us that the origins of this new musical cycle is for the most part rooted in the NO WAVE movement of which James Siegfried aka James White, aka James Chance is undoubtedly one of its most prominent figures. New York City was hands down the artistic telluric center of the second half of the 20th century, especially from the 70’s, on. Rising from the ashes of the Velvet Un- derground, a slew of local bands redefined the aesthetics of rock’n’roll which the merchants of the temple hastened to rename under various designations, such as Punk, New Wave, No Wave, Jazz-Funk or even Disco and Disco- Punk without forgetting to mention the original Electro designation pioneered by the band Suicide. One of the indispensable and emblematic figures of the mid-70’s is of course James Chance. James Siegfried, born in Milwaukee in 1953, began his musical journey on the piano at the age of seven. -

Crinew Music Re 1Ort

CRINew Music Re 1 ort MARCH 27, 2000 ISSUE 659 VOL. 62 NO.1 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Sony, Time Warner Terminate CDnow Deal Sony and Time Warner have canceled their the sale of music downloads. CDnow currently planned acquisition of online music retailer offers a limited number of single song down- CDnow.com only eight months after signing loads ranging in price from .99 cents to $4. the deal. According to the original deal, A source at Time Warner told Reuters that, announced in July 1999, CDnow was to merge "despite the parties' best efforts, the environment 7 with mail-order record club Columbia House, changed and it became too difficult to consum- which is owned by both Sony and Time Warner mate the deal in the time it had been decided." and boasts a membership base of 16 million Representatives of CDnow expressed their customers; CDnow has roughly 2.3 million cus- disappointment with the announcement, and said tomers. With the deal, Columbia House hoped that they would immediately begin seeking other to enter into the e-commerce arena, through strategic opportunities. (Continued on page 10) AIMEE MANN Artists Rally Behind /14 Universal Music, TRNIS Low-Power Radio Prisa To Form 1F-IE MAN \NHO During the month of March, more than 80 artists in 39 cities have been playing shows to raise awareness about the New Latin Label necessity for low power radio, which allows community The Universal Music Group groups and educational organizations access to the FM air- (UMG) and Spain's largest media waves using asignal of 10 or 100 watts. -

Ess Barbara 2770

Barbara ESS 1948, New York (États-Unis) Sans titre 1985 4/5 Tirage couleurs, à développement chromogène, contrecollé sur PVC 76 x 103 cm Née à New York en 1948, Barbara Ess obtient son Bachelor of Arts à l’University of Michigan en 1969 et sort diplômée de la London School of Film Technique, deux ans plus tard. Son travail est essentiellement photographique, utilisant plus particulièrement la technique du sténopé (en anglais pinhole = trou d’épingle), qui consiste en une boîte en carton percée d’un trou minuscule et garnie d’une plaque sensible reprenant le principe de la camera obscura . Elle réalise également des installations et des vidéos. En 1993, elle bénéficie d’une importante rétrospective au Queens Museum à New York. Barbara Ess se fait connaître grâce à son fanzine Just Another Asshole , en même temps qu’elle fait partie, à ses débuts, d’un girls-band new-yorkais appelé Disband , dont les membres sont plutôt artistes que musiciens (Barbara Kruger…). Elle joue et enregistre avec différents groupes de la scène underground ( Static , Y Pants , The Gynecologists ) jusqu’en 1978, tout en éditant de nombreux travaux d’artistes. Elle eut pour petit ami le compositeur guitariste Glenn Branca, icône du mouvement No Wave . C’est alors qu’elle se focalise sur la pratique du sténopé avec la longue pause qu’impose le sténoscope, l’impossiblité de régler la netteté, la distorsion quasi-obligatoire de l’image qui convoquent le trouble dans la lecture des images dévoilées. Brumeuses et distordues, les images de Barbara Ess naviguent entre l’hésitante objectivité supposée de la photographie et la re -présentation du sujet, brouillant sans cesse la perception qu’on a du monde matériel.