Cooking Culture with Eddie Huang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

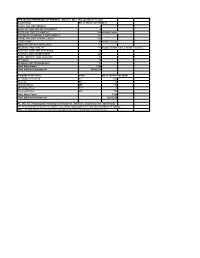

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

Macy's Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific

April 30, 2018 Macy’s Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Macy’s invites local tastemakers to share stories at eight stores nationwide, including the multitalented chef, best-selling author, and TV host, Eddie Huang in New York City on May 16 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- This May, Macy’s (NYSE:M) is proud to celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month with a host of events honoring the rich traditions and cultural impact of the Asian-Pacific community. Joining the celebrations at select Macy’s stores nationwide will be chef, best-selling author, and TV host Eddie Huang, beauty and style icon Jenn Im, YouTube star Stephanie Villa, chef Bill Kim, and more. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180430005096/en/ Macy’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebrations will include special performances, food and other cultural elements with a primary focus on moderated conversations covering beauty, media and food. For these multifaceted conversations, an array of nationally recognized influencers, as well as local cultural tastemakers will join the festivities as featured guests, discussing the impact, legacy and traditions that have helped them succeed in their fields. “Macy’s is thrilled to host this talented array of special guests for our upcoming celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,” said Jose Gamio, Macy’s vice president of Diversity & Inclusion Strategies. “They are important, fresh voices who bring unique and relevant perspectives to these discussions and celebrations. We are honored to share their important stories, foods and expertise in conversations about Asian and Pacific American culture with our customers and communities.” Multi-hyphenate Eddie Huang will join the Macy’s Herald Square event in New York City for a discussion about Asian representation in the media. -

Read Aloud Suggestions Belonging Picture Books

World Read Aloud day is a time to share stories both new and old! Use this opportunity to explore texts and authors that represent your community and search out stories that reveal experiences that are new and different from you own! Here are some of our favorite texts! Read Aloud Suggestions Belonging Picture Books The Gift of Nothing by Patrick McDonnell Giraffes Can’t Dance by Giles Anderae Too Many Tamales by Gary Soto Chicken Sunday by Patricia Polacco Llama Llama Misses Mama by Anna Dewdney Poetry “Night on the Neighborhood Street” by Eloise Greenfield The Flag of Childhood: Poems of the Middle East by Naomi Shihab Nye Chapter Books Wonder by RJ Palacio Fresh Off The Boat by Eddie Huang The Junkyard Wonders by Patricia Polacco Curiosity Picture Roxaboxen by Alice McLerran Sky Color by Peter Reynolds Hello Ocean by Pam Muñoz Ryan Journey by Aaron Becker Llama Llama Holiday Drama by Anna Dewdney litworld.org | Facebook: LitWorld | Twitter: @litworldsays | Instagram: @litworld Poetry “Salsa Stories” by Lulu Delacre A Light in the Attic by Shel Silverstein Chapter Books Bayou Magic by Jewell Parker Rhodes Unstoppable Octobia May by Sharon Flake Nightbird by Alice Hoffman Fortunately, the Milk by Neil Gaiman Friendship Picture The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend by Dan Santat The Friendly Four by Eloise Greenfield Ninja Bunny by Jennifer Gary Olsen Llama Llama and the Bully Goat by Anna Dewdney Poetry “Build a Box of Friendship” by Chuck Pool “Monsters I’ve Met” by Shel Silverstein Chapter James -

China's E-Tail Revolution: Online Shopping As a Catalyst for Growth

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute China’s e-tail revolution: Online e-tail revolution: shoppingChina’s as a catalyst for growth March 2013 China’s e-tail revolution: Online shopping as a catalyst for growth The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labor markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by two McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs and James Manyika. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI principals. Project teams are led by the MGI principals and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences

FROM PRINT TO SCREEN: ASIAN AMERICAN ROMANTIC COMEDIES AND SOCIOPOLITICAL INFLUENCES Karena S. Yu TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 ______________________________ Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. Department of Radio-Television-Film Supervising Professor ______________________________ Chiu-Mi Lai, Ph.D. Department of Asian Studies Second Reader Abstract Author: Karena S. Yu Title: From Print to Screen: Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences Supervisor: Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. In this thesis, I examine how sociopolitical contexts and production cultures have affected how original Asian American narrative texts have been adapted into mainstream romantic comedies. I begin by defining several terms used throughout my thesis: race, ethnicity, Asian American, and humor/comedy. Then, I give a history of Asian American media portrayals, as these earlier images have profoundly affected the ways in which Asian Americans are seen in media today. Finally, I compare the adaptation of humor in two case studies, Flower Drum Song (1961) which was created by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Crazy Rich Asians (2018) which was directed by Jon M. Chu. From this analysis, I argue that both seek to undercut the perpetual foreigner myth, but the difference in sociocultural incentives and control of production have resulted in more nuanced portrayals of some Asian Americans in the latter case. However, its tendency to push towards the mainstream has limited its ability to challenge stereotyped representations, and it continues to privilege an Americentric perspective. 2 Acknowledgements I owe this thesis to the support and love of many people. To Dr. Mallapragada, thank you for helping me shape my topic through both your class and our meetings. -

Recommended Books TITLES (AUTHORS)

Recommended Books TITLES (AUTHORS) Me & White Supremacy (Layla F. Saad) Things That Make White People Uncomfortable (Michael Bennett) Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? (Beverly Daniel Tatum) The New Jim Crow (Michelle Alexander) Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen (Jose Antonio Vargas) Sister Outsider (Audre Lorde) Freedom is a Constant Struggle (Angela Y. Davis) Born a Crime (Trevor Noah) So You Want to Talk About Race (Ijeoma Oluo) Bad Feminist (Roxane Gay) Dear White America (Tim Wise) Fresh Off the Boat (Eddie Huang) No Ashes in the Fire (Darnell L. Moore) You Can’t Touch My Hair (Phoebe Robinson) Between the World & Me (Ta-Nehisi Coates) Redefining Realness (Janet Mock) How to Be Black (Baratunde Thurston) A People’s History of the United States (Howard Zinn) Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil: The Life, Legacy, and Love of My Son Michael Brown (Lezley McSpadden) When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost (Joan Morgan) Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race (Reni Eddo-Lodge) I’m Judging You (Luvvie Ajayi) The Blood of Emmett Till (Timothy B. Tyson) The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Rebecca Skloot) Sister Citizen (Melissa V. Harris-Perry) Beyond the Messy Truth (Van Jones) Well That Escalated Quickly (Franchesca Ramsey) The Body is Not an Apology (Sonya Renee Taylor) White Fragility (Robin DiAngelo) Surpassing Certainty (Janet Mock) Living in the Tension: The Question for a Spir-itualized Racial Justice (Shelly Tochluk) Mom & Me & Mom (Maya Angelou) The Last Black Unicorn (Tiffany Haddish) We’re Going to Need More Wine (Gabrielle Union) I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness (Austin Channing Brown) Go Tell It on the Mountain (James Baldwin) The Color of Law (Richard Rothstein) The Autobiography of Malcolm X (Malcolm X as told to Alex Haley) Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching (Mychal Denzal Smith) So Close to Being the Sh*t, Y’all Don’t Even Know (Retta) Becoming (Michelle Obama) The Awkward Thoughts of W. -

Official Press Release

OFFICIAL PRESS RELEASE Contact: Ken Chen, Executive Director, The Asian American Writers’ Workshop Phone: (212) 494-0061 Email: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 26, 2011 WINNERS OF ASIAN AMERICAN LITERARY AWARD ANNOUNCED —Winners to be honored at PAGE TURNER: The Third Annual Asian American Literary Festival (10/29), featuring literary stars Jessica Hagedorn, Junot Díaz, Amitav Ghosh, Kimiko Hahn and many others — NEW YORK, October 26, 2011- the Asian American Writers' Workshop announced the winners of the Fourteenth Annual Asian American Literary Awards, the highest literary honor for writers of Asian American descent. The winners are Yiyun Li in fiction, Kimiko Hahn in poetry, and Amitava Kumar in nonfiction. Brief award citations to the winners and finalists are available at http://www.pageturnerfest.org/awards. Winners Kimiko Hahn and Amitava Kumar and finalists Molly Gaudry and Rahna Reiko Rizzuto will read at PAGE TURNER 2011: The Third Annual Asian American Literary Festival on October 29, 2011 from 11AM-7PM at powerHouse arena and Melville House in Brooklyn, NY. Featured writers include Jessica Hagedorn, Junot Díaz, Amitav Ghosh, Min Jin Lee, Jayne Anne Phillips, Teju Cole, Amitava Kumar, Kimiko Hahn, Hari Kunzru, and many more. The literary awards will be presented at the AFTERWORD party immediately after the festival at 8PM at Verso Press. The Asian American Literary Award in Fiction was awarded to Yiyun Li for her short story collection entitled Gold Boy, Emerald Girl (Random House). The award for fiction was judged by Whiting Writers’ Award winner Nami Mun, DSC Award finalist Tania James, and novelist Christina Chiu. -

{DOWNLOAD} Fresh Off the Boat: a Memoir

FRESH OFF THE BOAT: A MEMOIR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eddie Huang | 304 pages | 22 Nov 2013 | Random House USA Inc | 9780812983357 | English | New York, United States Fresh Off the Boat: A Memoir | Legal Outlet See all 23 - All listings for this product. Ratings and Reviews Write a review. Most relevant reviews. Good Value Book is in good condition, perhaps a little spendy for it being from a Goodwill - but still cheaper that big box store. Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. Greenlights by Matthew McConaughey Hardcover 5. Save on Nonfiction Trending price is based on prices over last 90 days. You may also like. Memoirs Paperback Books. Boats Paperback Books. Boating Paperback Books. Boats Vintage Paperback Magazines. Trade Paperback Books. This item doesn't belong on this page. Walker's girlfriend, Breonna Taylor, was fatally shot by plainclothes police officers in her Louisville, Ky. Walker was in the apartment at the time of the incident, and fired a warning shot at the officers, believing them […]. Washington, who produced Boseman's final film, was impressed by how the late star's future wife, Simone Ledward, doted on him. Sia responded to FKA twigs's lawsuit against the actor by tweeting that she has also "been hurt emotionally by Shia. The singer's Verzuz battle against Keyshia Cole had to be canceled due to her diagnosis. It was a rough week for theaters outside the box office, as hopes for a Congressional pandemic stimulus package were shut down yet again by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, while directors like Christopher Nolan and Denis Villeneuve were at the forefront of a backlash against Warner Bros. -

Fresh Off the Boat: Book Report

1 Fresh Off the Boat: Book Report Derrick Baber 2 COLD OPEN: Fade In: Jessica sits legs crossed at table with Ashley, Honey, and Samantha sipping coffee and reading magazines. Ashley appears frustrated and drops her magazine. Ashley “I’m not making dinner tonight. I’m just too tired” Ashley picks up house phone and calls husband’s work number Ashley “Hey Sweetie, I’m exhausted…how about dinner? Pause… “Great! Lets go to my favorite place, you know the one!” Jessica looks puzzled at Ashley while other women remain sipping coffee. Jessica “Wait…Ashley, you never named the restaurant. Does your husband just know all of your favorite things? Ashley “Yes of course! He forgot I hated salt on my popcorn when we saw Clueless a few weeks ago and I made sure he paid for it” Jessica “Interesting…hand me the phone” Ashley hands Jessica the phone and Jessica dials the number of Cattleman’s Ranch, asking for Louis Jessica “Hey Louis, lets go to that restaurant I love…see you there at 7?” Fade In: Louis hangs up phone with distressed look on face: Louis “O dear God” 3 Fade in: Split Screen showing Jessica sitting by herself at booth of restaurant while Louis, Eddie, Emery, and Evan sit at the table of another restaurant. Emery “I don’t think this is mom’s favorite place dad” Eddie “Yeah dad you’re screwed” Louis “This is going to be a very, very bad time for your father boys” Louis covers face with hands and groans Fade Out: End of COLD OPEN: 4 ACT ONE: Fade In: Eddie sits in classroom with writing on the board saying “BOOK REPORT DAY.” The students have been selecting names out of a hat that correspond to a list of remaining names on the board to write their book reports about. -

Six Words? We Exist Because These Stories Exist

WORD SIX S S T O R A I C E I S R O E F M IM A M TO I G GR IN AT M ION CO , IDENTITY, AND BY WRITERS FAMOUS & OBSCURE FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES EDITED BY BEST-SELLING LARRY SIX-WORD SMITH MEMOIRS SERIES Los Angeles • New York Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter in the current political environment, a handful of names have been changed at the request of the authors. Copyright © 2017 Larry Smith Fresh Off the Boat © 2017 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved. Published by Kingswell, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Kingswell, 1101 Flower Street, Glendale, California 91201. Editorial Director: Wendy Lefkon Executive Editor: Laura Hopper Cover Design by Shannon Koss ISBN 978-1-368-00838-9 FAC-020093-17202 Printed in the United States of America First Hardcover Edition, September 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Foreword by Nahnatchka Khan & Melvin Mar I was born in Las Vegas; both my parents were born in Iran. My family was full of characters: dad, mom, grandfather, aunts, uncles, (I remember one uncle telling us all to call him Panther) . and they all helped shaped my sense of humor. For me, being a first-generation American, coming from a family of immigrants, it was always impor- tant to tell stories from the inside out. -

Straus Literary 319 Lafayette Street, Suite 220 New York, New York 10012 646.843.9950

Straus Literary 319 Lafayette Street, Suite 220 New York, New York 10012 646.843.9950 www.strausliterary.com Agent: Jonah Straus [email protected] Foreign Rights on Offer – Frankfurt Book Fair 2018 FICTION The Tower of the Antilles Achy Obejas Finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction ● WORLD ENGLISH – AKASHIC BOOKS (SUMMER 2017) The Cubans in Achy Obejas’s story collection The Tower of the Antilles are haunted by islands: the island they fled, the island they’ve created, the island they were taken to or forced from, the island they long for, the island they return to, and the island that can never be home again. With language that is both generous and sensual, Obejas writes about existences beset by events beyond individual control, and poignantly captures how history and fate intrude on even the most ordinary of lives. Achy is one of Cuba’s most important writers, often writing about gay subculture and the Cuban Jewish community. She has won a Pulitzer prize for her reporting, as well as a Lambda award for her fiction. Her breakout novel, Days of Awe, was published by Ballantine in 2001 to resounding acclaim. “Deals with the conflicted relationships of Cubans, exiles, and Cuban-Americans have with their homeland, with the U.S., and, more poignantly, with each other.” — Rigoberto Gonzalez, in the Los Angeles Times “Like a long dream of many parts—Obejas is a master of the human, able to conjure her characters’ heartbeats right under your fingertips, their breaths in your ears.” —Alexander Chee, author of The Queen of the Night Ruins Achy Obejas ● WORLD ENGLISH – AKASHIC BOOKS (2009) Usnavy has always been a true believer. -

A Memoir Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FRESH OFF THE BOAT: A MEMOIR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eddie Huang | 288 pages | 04 Jun 2015 | Random House USA Inc | 9780812988536 | English | New York, United States Fresh off the Boat: A Memoir PDF Book August 17, Journey through Eddie's life as a Taiwanese immigrant son growing up in America, in a world filled with basketball, hip hop, fights, and drugs - to name a few hurdles. Shop Our Brands. Eddie Huang was raised by a wild family of FOB "fresh off the boat" immigrants--his father a cocksure restaurateur with a dark past back in Taiwan, his mother a fierce protector and constant threat. When was it that the culture of illiteracy and criminal worship became so hip that even smart people felt compelled to sound stupid and our culture embraced idiocy? Eddie recounts his childhood as an American born Chinese and all the cultural differences between him and "normal" Americans. After learning about his various exploits, some of which were extremely dangerous, I was amazed that he's still around to recount them. It is a raw memoir, foodie review, immigrant, abusive family story, and I'm not sure what else. Rating details. The author writes in a kind of boastful, over-the-top tone and for me personally the braggadociousness was Emotional and brashly told memoir of Eddie Huang's childhood, love of food, and exploration of being Asian-American. He wanted to open a restaurant that would fill both a hip-hop need and a desire for authentic Taiwanese food. His personal 4. Eddie Huang. We ate together, went shopping together, and worked together.