Teaching Eddie Huangâ•Žs Memoir Fresh Off the Boat and Its Trop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Dr. Joni M. Butcher E-Mail: [email protected] Office: 131 Coates Hall Office Hours: MWF 8:30-9:15; M & F: 11:30-12:15; Or by Appointment

CMST 3107–Rhetoric of Contemporary Media Fall 2017 Instructor: Dr. Joni M. Butcher e-mail: [email protected] Office: 131 Coates Hall Office Hours: MWF 8:30-9:15; M & F: 11:30-12:15; or by appointment Required Text: Foss, Sonja F. Rhetorical Criticism. Fourth edition. Waveland, 2009. Focus: This course will focus on the medium of television–specifically, television situation comedies. More specifically, we will evaluate and analyze television sitcoms theme songs from the 1960s to the present (with a brief exploration of the 1950s). We will use various methods of rhetorical criticism to help us understand how theme songs deliver powerful, compacted rhetorical statements concerning such cultural aspects as family, race relations, the anti-war movement, women’s liberation, social and class distinction, and cultural identity. Quote: “There is no sense talking about what TV is unless we also look at what TV was, where it came from – and where, in another sense, we’re coming from.” (David Bianculli, Teleliteracy: Taking Television Seriously) Favorite Quotes from Students: “I learned more about history in this class than in my history class. It’s like my history class—only fun!” “This class gave me lots of topics of conversation that I could use when I talk to anyone over 40.” “I learned that rhetorical criticism is a lot like opening a box of tools. You need the right tool for the job. Sometimes you think you might need a screwdriver, but then you find out a hammer really works better.” “I thought this class was really all about TV, but then I realized I could use these methods of criticism to analyze just about anything.” “I came to realize how time really does change people. -

AMA Journal of Ethics® July 2021, Volume 23, Number 7: E507-511

AMA Journal of Ethics® July 2021, Volume 23, Number 7: E507-511 FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF Invisibility of Anti-Asian Racism Audiey C. Kao, MD, PhD Parallels Imagine being confined and feeling trapped in your own house or apartment for months on end, afraid to leave the relative safety of your home because contact with other people could possibly bring you harm. Being isolated at home without an end in sight is no way to live. Fear, anxiety, depression, and even anger become your quarantine companions. During this past year, most of us can wholly grasp and empathize with this state of pandemic being. Now consider living this way for a reason other than a pandemic: your hesitancy and trepidation about walking out the door is because some hate you enough to harm you … just because of how you look. What is worse than being a target yourself is conjuring up a worst-case scenario befalling your mother or elderly family member halfway across the country or college-age nephews and nieces living away from home for the first time. This inescapable torment is the current reality for many Asians, Asian Americans, and Asian- appearing people in this country. Mob Murder Resurgence of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia during the COVID-19 pandemic is not surprising. On October 24, 1871, one of the largest mob lynchings in US history—the “Chinese Massacre”—took place in Los Angeles. According to a 1999 Los Angeles Times account: One by one, more victims were hauled from their hiding places, kicked, beaten, stabbed, shot and tortured by their captors. -

New Villager Layout

FIRST CLASS PRESORT PAID SUPERFAST WWeessttddaallee LOS ANGELES, Quarterly Newsletter of the CALIFORNIA Westdale Homeowners Association P.O.Box 66504 Los Angeles, California 90066 President www.westdalehoa.org Jerry Hornof ILLAGERILLAGER 310 391-9442 jerry.horno [email protected] VV Editor Winter 2017 Quarterly Newsletter of the Westdale Homeowners Association Marjorie Templeton 310 390-4507 [email protected] Advertising Ina Lee P RESIDENT ’ S M ESSAGE 310-397-5251 [email protected]. Editor/Graphic Designer ESTDALE ARES Dick Henkel W C [email protected] •Jerry Hornof The Westdale Homeowners Association's 2017 theme is Westdale Cares. We live in a wonderful neighborhood in Los Angeles. To sustain the features we love in • INSIDE • Westdale, it will require building a larger community of participants. There is a myriad of ways to get involved MEMBERSHIP TIME in the community with various time commitments. Please consider participating. In this message I want to highlight two issues • W ESTDALE H OMEOWNERS A SSOCIATION • • CALL FOR ARTICLES and two events. These provide an opportunity for your active involvement • and/or enjoyment. The first issue is the Great Streets initiative impacting Venice Boulevard WESTDALE PUBLISHER between Inglewood Boulevard and Beethoven Street. The intent was to develop • four new pedestrian crossings, a safer road design featuring protected and SAFETY REPORT buffered bike lanes, and improvements at existing signalized intersections. • Combined, these changes could serve to help make the street the “small town downtown” for Mar Vista. The challenge has been the loss of traffic lanes and GETTING TO KNOW the increased congestion in that corridor. The Mar Vista Community Council OUR NEIGHBORS (MVCC) has debated this issue. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

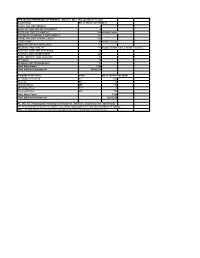

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Macy's Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific

April 30, 2018 Macy’s Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Macy’s invites local tastemakers to share stories at eight stores nationwide, including the multitalented chef, best-selling author, and TV host, Eddie Huang in New York City on May 16 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- This May, Macy’s (NYSE:M) is proud to celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month with a host of events honoring the rich traditions and cultural impact of the Asian-Pacific community. Joining the celebrations at select Macy’s stores nationwide will be chef, best-selling author, and TV host Eddie Huang, beauty and style icon Jenn Im, YouTube star Stephanie Villa, chef Bill Kim, and more. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180430005096/en/ Macy’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebrations will include special performances, food and other cultural elements with a primary focus on moderated conversations covering beauty, media and food. For these multifaceted conversations, an array of nationally recognized influencers, as well as local cultural tastemakers will join the festivities as featured guests, discussing the impact, legacy and traditions that have helped them succeed in their fields. “Macy’s is thrilled to host this talented array of special guests for our upcoming celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,” said Jose Gamio, Macy’s vice president of Diversity & Inclusion Strategies. “They are important, fresh voices who bring unique and relevant perspectives to these discussions and celebrations. We are honored to share their important stories, foods and expertise in conversations about Asian and Pacific American culture with our customers and communities.” Multi-hyphenate Eddie Huang will join the Macy’s Herald Square event in New York City for a discussion about Asian representation in the media. -

Pdf, 152.22 KB

00:00:00 Music Music Gentle trilling music with a steady drumbeat plays under the dialogue. 00:00:01 Promo Promo Speaker: Bullseye with Jesse Thorn is a production of MaximumFun.org and is distributed by NPR. [Music fades out.] 00:00:12 Music Music “Huddle Formation” from the album Thunder, Lightning, Strike by The Go! Team. A fast, upbeat, peppy song. Music plays as Jesse speaks, then fades out. 00:00:20 Jesse Host It’s Bullseye. I’m Jesse Thorn. Kathryn Hahn is an actor. She’s been in comedy films like Stepbrothers, the Anchorman movies. Many more. On TV, she starred in the NBC show, Crossing Jordan. She was also on Parks and Rec. She played Jennifer Barkley, the political consultant. She played a rabbi on the TV show Transparent. She starred in her own HBO drama called Mrs. Fletcher. I guess what I’m saying is: she has range. And here’s an example. She has an amazing supporting role on Wandavision, the bonkers new show on Disney+. I’m not gonna spend a ton of time explaining the plot of Wandavision. It’s set in the Marvel Universe, [chuckling] sometimes requires some prior knowledge. It stars Elizabeth Olsen and Paul Bettany as Wanda Maximoff and Vision, respectively. The two of them are superheroes who have settled down in a New Jersey suburb where—wouldn’t you know it—not everything is what it seems. Kathryn Hahn plays their neighbor, Agnes, who’s also hiding some secrets. The show has really taken off lately thanks in part to a very fun meme where Kathryn Hahn winks. -

Read Aloud Suggestions Belonging Picture Books

World Read Aloud day is a time to share stories both new and old! Use this opportunity to explore texts and authors that represent your community and search out stories that reveal experiences that are new and different from you own! Here are some of our favorite texts! Read Aloud Suggestions Belonging Picture Books The Gift of Nothing by Patrick McDonnell Giraffes Can’t Dance by Giles Anderae Too Many Tamales by Gary Soto Chicken Sunday by Patricia Polacco Llama Llama Misses Mama by Anna Dewdney Poetry “Night on the Neighborhood Street” by Eloise Greenfield The Flag of Childhood: Poems of the Middle East by Naomi Shihab Nye Chapter Books Wonder by RJ Palacio Fresh Off The Boat by Eddie Huang The Junkyard Wonders by Patricia Polacco Curiosity Picture Roxaboxen by Alice McLerran Sky Color by Peter Reynolds Hello Ocean by Pam Muñoz Ryan Journey by Aaron Becker Llama Llama Holiday Drama by Anna Dewdney litworld.org | Facebook: LitWorld | Twitter: @litworldsays | Instagram: @litworld Poetry “Salsa Stories” by Lulu Delacre A Light in the Attic by Shel Silverstein Chapter Books Bayou Magic by Jewell Parker Rhodes Unstoppable Octobia May by Sharon Flake Nightbird by Alice Hoffman Fortunately, the Milk by Neil Gaiman Friendship Picture The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend by Dan Santat The Friendly Four by Eloise Greenfield Ninja Bunny by Jennifer Gary Olsen Llama Llama and the Bully Goat by Anna Dewdney Poetry “Build a Box of Friendship” by Chuck Pool “Monsters I’ve Met” by Shel Silverstein Chapter James -

China's E-Tail Revolution: Online Shopping As a Catalyst for Growth

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute China’s e-tail revolution: Online e-tail revolution: shoppingChina’s as a catalyst for growth March 2013 China’s e-tail revolution: Online shopping as a catalyst for growth The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labor markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by two McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs and James Manyika. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI principals. Project teams are led by the MGI principals and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences

FROM PRINT TO SCREEN: ASIAN AMERICAN ROMANTIC COMEDIES AND SOCIOPOLITICAL INFLUENCES Karena S. Yu TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 ______________________________ Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. Department of Radio-Television-Film Supervising Professor ______________________________ Chiu-Mi Lai, Ph.D. Department of Asian Studies Second Reader Abstract Author: Karena S. Yu Title: From Print to Screen: Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences Supervisor: Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. In this thesis, I examine how sociopolitical contexts and production cultures have affected how original Asian American narrative texts have been adapted into mainstream romantic comedies. I begin by defining several terms used throughout my thesis: race, ethnicity, Asian American, and humor/comedy. Then, I give a history of Asian American media portrayals, as these earlier images have profoundly affected the ways in which Asian Americans are seen in media today. Finally, I compare the adaptation of humor in two case studies, Flower Drum Song (1961) which was created by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Crazy Rich Asians (2018) which was directed by Jon M. Chu. From this analysis, I argue that both seek to undercut the perpetual foreigner myth, but the difference in sociocultural incentives and control of production have resulted in more nuanced portrayals of some Asian Americans in the latter case. However, its tendency to push towards the mainstream has limited its ability to challenge stereotyped representations, and it continues to privilege an Americentric perspective. 2 Acknowledgements I owe this thesis to the support and love of many people. To Dr. Mallapragada, thank you for helping me shape my topic through both your class and our meetings.