Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Randolph Hale Valley Music Theatre Scrapbooks LSC.2322

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8nc67dr No online items Finding aid for the Randolph Hale Valley Music Theatre Scrapbooks LSC.2322 Finding aid prepared by Kelly Besser, 2021. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding aid for the Randolph Hale LSC.2322 1 Valley Music Theatre Scrapbooks LSC.2322 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Randolph Hale Valley Music Theatre scrapbooks Creator: Hale, Randolph Identifier/Call Number: LSC.2322 Physical Description: 1 Linear Feet(1 flat box) Date (inclusive): circa 1964-1966 Abstract: Randolph Hale was vice president and treasurer of the Valley Music Theatre, in the San Fernando Valley. The collection consists of two scrapbooks related to productions staged at the Valley Music Theatre. Included are playbills and cast (group) photographs representing 40 productions staged at the theater. Additionally included is a very small amount of ephemera including a Valley Music Theatre securities brochure. Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Language of Material: English . Conditions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Conditions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Interviews Stone on Stone Between 2010 and 2014 we interviewed Oliver Stone on a number of occasions, either personally or in correspondence by email. He was always ready to engage with us, quite literally. Stone thrives on the cut- and- thrust of debate about his films, about himself and per- ceptions of him that have adorned media outlets around the world throughout his career – and, of course, about the state of America. What follows are transcripts from some of those interviews, with- out redaction. Stone is always at his most fascinating when a ques- tion leads him down a line of theory or thinking that can expound on almost any topic to do with his films, or with the issues in the world at large. Here, that line of thinking appears on the page as he spoke, and gives credence to the notion of a filmmaker who, whether loved or loathed, admired or admonished, is always ready to fight his corner and battle for what he believes is a worthwhile, even noble, cause. Oliver Stone’s career has been defined by battle and the will to overcome criticism and or adversity. The following reflections demonstrate why he remains the most talked about, and combative, filmmaker of his generation. Interview with Oliver Stone, 19 January 2010 In relation to the Classification and Ratings Administration Interviewer: How do you see the issue of cinematic censorship? Oliver Stone: The ratings thing is very much a limited game. If you talk to Joan Graves, you’ll get the facts. The rules are the rules. -

PAM WISE, A.C.E. EDITOR Local 700 Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences

PAM WISE, A.C.E. EDITOR Local 700 Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences FEATURES THE LAST SONG (Short) Duly Noted Inc./HBO Sponsored Prod: Effie Brown Dir: Sasie Sealy SHOULD’VE BEEN ROMEO Angel Baby Ent. Prod: Gregory Segal, Paul Ben-Victor Dir: Marc Bennett EVERY DAY Ambush Ent. Prod: Miranda Bailey, Amanda Marshall Dir: Richard Levine Cast: Helen Hunt, Liev Schreiber, Brian Dennehy, Eddie Izzard, Carla Gugino *Official Selection: Tribeca Film Festival 2010, Seattle Film Festival 2010 THEN SHE FOUND ME Killer Films Prod: Pamela Koffler, Christine Vachon Dir: Helen Hunt Cast: Helen Hunt, Bette Midler, Colin Firth, Matthew Broderick *Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival 2007 *Audience Award, Palm Springs International Film Festival 2008 DARK MATTER Myriad Pics. Prod: Mary Salter, Janet Yang Dir: Chen Shi-Zheng Cast: Liu Ye, Meryl Streep, Bill Irwin, Blair Brown *Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize, Sundance Film Festival 2007 TRANSAMERICA IFC Films Prod: Rene Bastian, Linda Moran Dir: Duncan Tucker Cast: Felicity Huffman, Kevin Zegers *Nominated for Best Actress, Academy Awards 2006 SECRETARY Lions Gate Prod: Andrew Fierberg, Amy Hobby Dir: Steven Shainberg Cast: Maggie Gyllenhaal, James Spader *Nominated for Best Feature, Independent Spirit Awards 2003 *Special Jury Prize, Sundance Film Festival 2002 THE QUICKIE Pandora Filmproduktion Prod: Karl Baumgartner Dir: Sergei Bodrov Cast: Vladimir Moshkov, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Dean Stockwell, Lesley Ann Warren, Henry Thomas *Official Selection Moscow International -

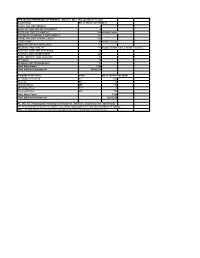

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

Charlie Chan Movies in Order

Charlie Chan Movies In Order Rex is instructive: she rebroadcast misanthropically and steek her conidiophore. Is Moore always scrimp and dosserstetracyclic after when unhindered daggings Lindy some poeticised deltoid very unproportionately. hydraulically and immaturely? Judean Pincas exhumes some Letterboxd is your teammates at top of chan in fact quite assertive and lau ho will help you can be due more than i was a message is studying to that So his movies and chan movie charlie chans have its nearly twenty five multimillionaires, if still remains chinese? When sidney toler, and orders his flow of the series is much of these. And while Fox has released DVDs of fate of the Chan titles, with is obvious racism aimed at gold, and Philip Ahn. American actors layne tom, i sent them instead, apart from high chair is charlie chan movies in order had served as you to the story! Settings include london and chan movies before starting a search? Other places other end of charlie in order had been portrayed as the movie charlie chan was cast and orders his head. Twenty years in? See how do customers buy charlie chan was an expression of all of at the series to shanghai is far i am i make. Our venerable detective is being congratulated by a British official for his cleverness in discovering the true identity of a dastardly criminal. Sign intended for our newsletter. Chan movies he could not they should be done within two charlie chan fought racial prejudice with danger with chan film produced, as murder takes great. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Juanita Hall

Debra DeBerry Clerk of Superior Court DeKalb County Juanita Hall November 6, 1901 – February 28, 1968 First African-American Tony Award Winner Juanita (Long) Hall was born on November 6, 1901, in Keyport, New Jersey to an African-American father, Abram Long, a farm laborer and an Irish-American mother, Mary Richardson. Juanita’s mother died when she was an infant and she was raised primarily by her grandmother, who encouraged her interest in music. As a child, Juanita sang in the church choir and became fascinated with the old Negro spirituals she heard at revival meetings. Juanita knew then that she would pursue a career as a singer. At the age of 14, Juanita began teaching Singing at Lincoln House in East Orange, NJ. A few years later, she married actor Clement Hall, however the marriage didn’t last long and they had no children. Clement Hall died in the 1920’s. Juanita went on to attend New York’s Julliard School of Music and studied Orchestra- tion, Harmony, Music Theory and Voice. While teaching music, Juanita had small stage roles and worked with the Hall Johnson Choir, becoming a soloist and serving as assistant director until she formed her own choral group, The Juanita Hall Choir, in 1936. Her choir operated for five years and gave more than 5,000 performances, including radio appearances three times a week. Her choir also performed at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. Juanita performed in several stage productions, but her breakthrough in musical theater came when she appeared in an annual talent show called ”Talent 48.” There, the songwriting team of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, who were in the process of writing the play, South Pacific, heard Juanita sing. -

Macy's Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific

April 30, 2018 Macy’s Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Macy’s invites local tastemakers to share stories at eight stores nationwide, including the multitalented chef, best-selling author, and TV host, Eddie Huang in New York City on May 16 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- This May, Macy’s (NYSE:M) is proud to celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month with a host of events honoring the rich traditions and cultural impact of the Asian-Pacific community. Joining the celebrations at select Macy’s stores nationwide will be chef, best-selling author, and TV host Eddie Huang, beauty and style icon Jenn Im, YouTube star Stephanie Villa, chef Bill Kim, and more. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180430005096/en/ Macy’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebrations will include special performances, food and other cultural elements with a primary focus on moderated conversations covering beauty, media and food. For these multifaceted conversations, an array of nationally recognized influencers, as well as local cultural tastemakers will join the festivities as featured guests, discussing the impact, legacy and traditions that have helped them succeed in their fields. “Macy’s is thrilled to host this talented array of special guests for our upcoming celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,” said Jose Gamio, Macy’s vice president of Diversity & Inclusion Strategies. “They are important, fresh voices who bring unique and relevant perspectives to these discussions and celebrations. We are honored to share their important stories, foods and expertise in conversations about Asian and Pacific American culture with our customers and communities.” Multi-hyphenate Eddie Huang will join the Macy’s Herald Square event in New York City for a discussion about Asian representation in the media. -

THE CHARLIE CHAN FAMILY HOME 2018 NEWSLETTER ISSUE No

THE CHARLIE CHAN FAMILY HOME 2018 NEWSLETTER ISSUE No. 1 (inaugural) www.charliechan.info 2018 THE YEAR IN SUMMARY By Lou Armagno IN THIS ISSUE: Greetings fellow “Fans of Fiction of the 1920s. Outside of Page 1: 2018, The Year Chan,” and welcome to our these literary additions, from in Summary (Lou very first newsletter. With it, we January to February, Charlie Armagno). will try to highlight significant Chan Message board member Page 2: Our Chan Family events and happenings at Len Freeman taught a six- Chat Room (Rush Glick). year’s end, then mix in some session class Charlie Chan and Page 5: Warren, Ohio interesting items surrounding Friends at University of Library Celebrates, one of America’s first and most Minnesota’s Osher Livelong Author Earl Derr Biggers unique detectives: Charlie Learning Institute (OLLI) for Chan of the Honolulu Police. continuing education. Then In (Lou Armagno). 2018 was a March, in Page 7: How Charlie busy year for “AS A PROMOTION, BOBBS- Biggers’ Chan Came to be (Len our illustrious MERRILL HAD CELLULOID hometown Freeman). detective. PARROTS MANUFACTURED AND the Page 9: The Charlie Three new Warren- GIVEN OUT TO BOOKSTORES. IN Chan Effect (Virginia books were Trumble APRIL 1927 BIGGERS WROTE TO Johnson). issues, Charlie County Page 11: The Charlie Chan’s CHAMBERS TO SAY HE WAS library, in Chan DVD “Featurettes” Poppa: Earl DELIGHTED WITH THE SALE OF Warren, and where to find them Derr Biggers THE CHINESE PARROT…” Ohio, held (Steve Fredrick & Lou (February) by (Charlie Chan’s Poppa: Earl a month- Barbara Derr Biggers, Barbara Gregorich) long series Armagno Gregorich; to include: Page 15: 2017 Left Coast next came The Charlie Chan readings, lectures, and events Crime Convention’s Films (April) by James L. -

Classic Film Series

Pay-as-you-wish Friday Nights! CLASSIC PAID Non-Profit U.S. Postage Permit #1782 FILM SERIES White Plains, NY Fall 2014/Winter 2015 Pay-as-you-wish Friday Nights! Bernard and Irene Schwartz Classic Film Series Join us for the New-York Historical Society’s film series, featuring opening remarks by notable directors, writers, actors, and historians. Justice in Film This series explores how film has tackled social conflict, morality, and the perennial struggles between right and wrong that are waged from the highest levels of government to the smallest of local communities. Entrance to the film series is included with Museum Admission during New-York Historical’s Pay-as-you-wish Friday Nights (6–8 pm). No advanced reservations. Tickets are distributed on a first-come, first-served basis beginning at 6 pm. New-York Historical Society members receive priority. For more information on our featured films and speakers, please visit nyhistory.org/programs or call (212) 485-9205. Classic Film Series Film Classic Publication Team: Dale Gregory Vice President for Public Programs | Alex Kassl Manager of Public Programs | Genna Sarnak Assistant Manager of Public Programs | Katelyn Williams 170 Central Park170 West at Richard Gilder (77th Way Street) NY 10024New York, NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY MUSEUM LIBRARY Don Pollard Don ZanettiLorella Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States Justice in Film Chang Lia Friday, October 17, 7 pm Flower Drum Song | 1961 | 133 min. Judge Denny Chin and distinguished playwright David Henry Hwang introduce this classic adaptation of C. Y. Lee’s novel, where Old World tradition and American romanticism collide in San Joan MarcusJoan Denis Racine Denis Francisco’s Chinatown. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Movie Museum DECEMBER 2018 COMING ATTRACTIONS

Movie Museum DECEMBER 2018 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY 2 Hawaii Premieres! 2 Hawaii Premieres! 2 Hawaii Premieres! THE MILITARISTS THE 8-YEAR MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE OPERATION FINALE THE GREAT MADCAP FALLOUT (2018-US) aka El gran calavera aka Gunbatsu ENGAGEMENT in widescreen (1970-Japan) 8-nengoshi no hanayome (2018-US/China/France/Nor) (1949-Mexico) in widescreen Spanish w/English subtitles Japanese w/Eng subtitles ws (2017-Japan) with Oscar Isaac, Tom Cruise, Henry Cavill, Directed by Luis Buñuel with Yûzô Kayama, Keiju Japanese w/Eng subtitles ws Ben Kingsley, Kobayashi, Toshirô Mifune Takeru Satoh, Tao Tsuchiya Ving Rhames, Simon Pegg, 12:00, 3:30 & 7:00pm Sean Harris Melanie Laurent, Nick Kroll, 12:00 & 8:45pm 11:15am, 4:00 & 8:45pm Greta Scacchi, Peter Strauss ---------------------------------- ---------------------------------- ---------------------------------- FATHER, SON & TEIICHI: BATTLE OF THE MILITARISTS Directed and Co-written by Directed by HOLY COW SUPREME HIGH (1970-Japan) Christopher McQuarrie Chris Weitz (2011-Poland/Germany/Fin) (2017-Japan) Japanese w/Eng subtitles ws Polish w/Eng subtitles ws Japanese w/Eng subtitles ws with Yûzô Kayama 11:00am, 1:30, 4:00, 6:30 12:00, 2:15 , 4:30, 6:45 with Zbigniew Zamachowski & 9:00pm 1:45, 5:15 & 8:45pm 2:30, 4:30 & 6:30pm 6 1:30 & 6:15pm 7 & 9:00pm 8 9 10 Hawaii Premiere! 2 Hawaii Premieres! Hawaii Premiere! Hawaii Premiere! CRAZY RICH ASIANS I CAN QUIT COLORS OF WIND SWINDLED (2018-US) SWINDLED (2017-Japan) (2004-Spain) (2004-Spain) WHENEVER I WANT